I walk to the corner store in slippers and pajamas. It’s Sunday and I slept in, sort of, though not as late as I’d have liked. Early-bird habits are tough to break on weekends. The light, skittish sleep that’s only good for getting me through the night—there’s no comparing it to the deep and morbid plunges I often take into dark chasms during daytime naps. Three, five, even seven times. I’m no longer afraid to roam the musty tunnels of the unconscious. I enjoy it, actually. So I’d rather get up early, have breakfast, and take one of my heavy siestas later on, resting my head on the desk or table while the others chat, on the bus, in the library, at the temple. Sleeping at the temple is my favorite. No one can tell me off for being narcoleptic.

The sun is shining by now, setting ablaze the stone wall and its coat of bougainvillea, the façade of the orange house, the white wall at the end of the street. I should have worn sunglasses. I buy four rolls and two pineapple empanadas. I also pick up a can of salsa and a cup of beans sealed with plastic wrap and a rubber band. We’ll make molletes. I break off a little piece of bread and stick it in my mouth. It’s almost unchewably tough. I leave the store and cross the street to buy the newspaper. The soles of my slippers are flimsy and the sharp stones of the median strip dig into my feet.

A few feet from the newsstand, I recognize him. His face is on the cover of a tabloid. My hands shake as I try to extract the magazine from the line where it’s hung on a clothespin for display. The woman who runs the stand snatches away the pin, scolding me. The copies for sale are stacked to one side, weighed down with a hunk of cement. I take one and ask for the Sunday paper we always buy. My hand is still trembling when I hold out the coins. I drop an empanada as I try to press the bundle of papers under my arm while keeping hold of the bread bag, the cup of beans, the can of salsa roja.

I leave the empanada where it fell, beside a planter, for the birds to peck at. I wait impatiently for the light to change, then cross to the median strip. I’ll never be able to open one of those tabloids at home without getting interrogated, so I decide to sit there, on a metal bench. I spread out the paper and read. First I look. Yes, it’s him. The butter man, who else? “Movie Marathon,” reads the derisive headline in big white letters.

His face is barely distinguishable in the photo. Flanked by police officers, he’s dirty and disheveled, his eyes cast low. Looking like that, he could have passed for any old bum, but it’s him, I recognize the brown sweater draped over his shoulders, sleeves drooping like an extra pair of dead arms, and that blue striped shirt of his, or what’s left of it after . . . eight years.

There’s also a photo of his lair, which may be a hovel but still looks pretty comfortable to me, well equipped for forgetting all about the outside world. Just as I remembered, the walls are padded with scraps of carpet and there are posters taped up on top of each other. In a corner, there’s still the same sack filled with foam rubber, molded to the shape of his back, along with a heap of rumpled blankets and a dozen notebooks lined up neatly in a crate.

The article describes what they found during the theater renovation, joking indulgently with the ruthless humor of sensationalist journalism. He didn’t say a word. The manager, meanwhile, claims to be as shocked as anyone else: “I didn’t know, I didn’t suspect a thing. It’s like someone up and told me I had an alien in the trunk of my car. Let the authorities investigate, I have nothing to do with it.” Then he talks about preventative measures to ensure that such an incident never happens again, and seizes his chance to advertise the new concept of VIP movie theaters: reclining seats, air conditioning, surround sound. “Now lots of folks are going to want to move in with us,” he quips.

![]()

I must have been about twelve, though I’m not totally sure. I know I wasn’t in sixth grade yet. In fact, I bet it was summer break when I met the butter man. There was a whole battalion of us, maybe ten or fifteen kids, all cousins or friends or neighbors. We’d go to the movies at the Multicinema under the leadership of my sister, who was both the oldest and apparently the most mature, though I had my doubts. She’d worked hard to earn this reputation, but all she did in those days was daydream about her beloved Fabrizzio, an absolute idiot from a so-called good family who turned out to be a pathetic has-been and a humorless cheapskate. He acted as if he were doing my sister a favor by giving her the time of day, since he didn’t even acknowledge that they were a couple. Fabrizzio only wanted to be admired and my sister did exactly that. I was furious with her. And with everyone else. At eleven, being furious with everyone is a natural state, which I guess is something that doesn’t really go away, you just get tired of showing it.

I didn’t get along with anyone in the group. And “didn’t get along” was just another way of saying I didn’t fit in. I was forced to keep ranks in the freak army, and my sister, my sole ally, was busy being bewitched by Fabrizzio the moron.

The only thing that had dragged me there, besides my mother’s imploring gaze, was that we were supposed to see Robin Hood, with Kevin Costner. But no, Fabrizzio roped us all into seeing some Van Damme movie instead, God knows what it was called. Enraged, I stomped into the theater and sat all the way down in the second row, by the emergency exit, far from all the others.

During the movie, I’d turn around to look at my sister, her face fixed in an idiotic smile, pretending to be wowed by Van Damme’s martial feats as she ogled Fabrizzio. I fumed with jealousy. When the movie was almost over, I decided to put her careless contempt on full display. I slunk down in my seat so they wouldn’t see me when the lights went up. As soon as she came looking for me, worried, I would pretend I’d been overcome by one of my bouts of narcolepsy, and she’d feel so guilty that she’d forget all about stupid Fabrizzio and focus her full attention on me. It was Thursday and the theater was nearly deserted. Besides our pack of imbeciles, there may have been two or three other people sitting toward the middle and upper rows. They didn’t make much noise as they left. My sister wouldn’t stop gushing and cooing and beaming at Fabrizzio even for a second, and I fell into a deep sleep.

When I woke, the theater was empty and completely dark. “Laura,” I called, but the darkness didn’t answer. I felt as abandoned as Hansel and Gretel being led into the forest to die. Laura had forgotten about me as readily as if I were scattered popcorn, crumpled bags, nibbled paper cups.

I felt my way up the stairs and reached the exit to the main lobby. The doors were locked. From up above, I could make out the outline of the seats, the neon emergency exit sign, the smudge of the screen like a dim rectangular moon, floundering into a terrifying horizon. The emergency exit was locked, too. Out of fear or rage, I couldn’t tell which, I burst into tears.

When I’d worn myself out crying and lifted my head, I saw a slit of light alongside one of the wall panels that lined the hall, right by the door to the corridor. My senses sharpened and I thought I heard the murmur of a portable radio. Now that I think about it, I bet the butter man actually heard me crying, maybe even saw me sitting there, hunched over on the carpeted steps with my face between my knees, and waited for me to notice him so he wouldn’t freak me out. I got up to peer through the crack, which revealed a Libro Vaquero comic book and a flashlight.

I knocked on the panel, assuming it was a door and the man on the other side was the security guard. “Sir, I’m locked in,” I called. “Could you let me out?” Slowly, he rose to his feet, switched off the radio, unhooked the flashlight from the shoelace he’d hung it from, and shifted the panel to one side, like a stiff curtain. When he stepped out, he glanced around like a rodent leaving its burrow, which I didn’t find odd at the time. I explained that I’d fallen asleep, that I’d come with my sister and her friends, who’d left me behind. He used the flashlight to study my face. I couldn’t see his, but I pictured him as I pictured all security guards: flabby, gloomy men, weighed down with exhaustion and monotonous routines. “You fell asleep,” he echoed, incredulous, in a voice that sounded too alert to me, the voice of a young man. I recited my usual explanation of narcolepsy; by then I’d memorized what I needed to tell people who’d never heard of the disorder. No one knew much about any disorders in the early nineties. The butter man seemed confused or indecisive. He swiveled the beam of the flashlight across the hall without a word. I expected him to suddenly procure a heavy wad of keys, jangling them in his hands as he headed for the exit, where he’d lead me to a phone and scold my sister and parents for their oversight. Instead, he seemed apprehensive, uneasy: “This way,” he ventured, as if I were capable of hurting him. He lifted the latch on the panel and motioned me inside.

I started to doubt he was a security guard at all and felt a flash of preteen alarm. I’d received countless lectures on not talking to strangers. But there was also something that made me trust him. Was it his voice? The smell of warm butter? I stepped into his lair. I remember suddenly longing to live there myself. The space had a warm, cozy feel to it, like a blanket fort in the living room or a little tree house. But I didn’t have time to take in the details, because he led me through a narrow opening between the walls and over a thick pipe, maybe twenty centimeters around, that seemed to run through the entire theater. I could feel the sweat of the brick walls, the damp lapping at my arms like a cat’s tongue. On the other side, a pillar of light announced the exit. The butter man pressed a finger to his lips and turned off the flashlight that had shone onto my feet as we went. The mouth of the passageway was blocked by an acrylic screen. On the other side of the screen was a poster of Beauty and the Beast, which I could make out from the back. The man asked me to step aside so he could peer around the edge of the screen, although the space was so tiny that it was impossible to step aside, so he was actually just warning me not to panic when he crowded me there. That’s when I realized I should call him the butter man. To this day, whenever anyone makes a bag of popcorn I think of him, warm and feverish and fragile. A little mouse like the kind you can buy at a pet store, quivering in your open palm. A tepid creature, suffused with the scent of butter, that carefully moved the screen just enough for us to slip out.

The man went straight to the soda fountain, as if he’d forgotten I was with him. Now that there was enough light for me to get a good look, I saw that he couldn’t possibly be a security guard. He was barely taller than I was and so skinny he looked breakable. He reminded me of emaciated figures in photos from the Holocaust, an image intensified by his shapeless striped shirt and sagging pants. He opened the freezer and took out a cup of Neapolitan ice cream that he proceeded to eat in four spoonfuls. I sat on one of the stools at the counter, gaping dumbly at his every move: he opened the hot dog roller and brought the kitchen to life with the deft hands of an orchestra conductor. He placed four hot dogs in four buns slathered in mayonnaise. He looked up to ask: Onion? Dazed, I shook my head, as if a ghost were making me dinner. He pushed me a paper plate with my hot dog, no onion, and wolfed down the first of the three he’d made for himself, piled with tomato and pickled chiles. Then he went to the fridge for a drink and took out a bottle of Mirinda orange soda for me, this time without asking. I liked Mirinda. Although, truth be told, I’m not sure if I liked Mirinda already or if that’s when I developed a taste for it.

I finished my hot dog and asked if I could have another. He smiled, pleased. He took his time to assemble this one, squeezing out little waves of ketchup and mustard like in the commercials. I hadn’t yet registered how strange it was to be there. Maybe it wouldn’t fully hit me until later. All the dense darkness of the night was pooling on the other side of the glass doors. Not a single car passed by and the streetlamps were waiting for daybreak. The butter man glanced at his watch. A very elegant watch, it seemed to me, practically jewelry. He took a final swig of soda and placed the two glass bottles by the grate, I guess to avoid suspicion.

He asked if I liked horror movies and I shrugged: I wasn’t allowed to watch them, I explained. Once again, he pressed a finger to his lips and motioned for me to follow. We made our way down a long corridor that led to the different screens until we reached the very last door, a tiny room, a veritable shoebox of a theater. It can’t have fit more than thirty people. The screen was lit and showed the closing credits of a movie. He told me in a whisper to sit by the door. Minutes later, Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare started to roll. After twenty minutes, I’d bitten my nails to the quick and yanked out a hangnail that hurt like a mortal wound. He left halfway through the movie and returned with a bag of popcorn, two sodas, and a cup of Neapolitan ice cream for me. Then I went out because I had to pee. By the time I came back, the butter man was gone. So was the rest of the food. I waited for the Freddy Krueger movie to end, but there was no sign of him. Suddenly I had to clap a hand over my mouth to contain my excitement: Robin Hood had begun.

I knew this was all very wrong, but I wanted to teach Laura and my parents a lesson, wanted them to worry about me for once, to remember I existed. Of course, I also wanted to see Robin Hood. The last thing I remember is Marian’s autumnal wedding, her red curls adorned with a lovely headdress of flowers and dry leaves. I vowed to myself that I’d wear one just like it when I got married, in the woods, golden leaves raining down from the treetops. I woke up a little while later, frozen stiff in the very same spot, huddling numb by the theater door in the dark. I stumbled out to the lobby. The blue dawn had started seeping through the glass doors. I reached out to touch one of the bolts. It was open. There, in the ticket booth, was the night guard, who really was exactly as I’d pictured him: gloomy, flabby, small. He was lying on some flattened cardboard boxes with the light on, fast asleep in his undershirt. I crossed the parking lot and looked for a pay phone.

There weren’t many blocks between the theater and my house, but I waited in the cold for my parents to come get me before I offered the necessary explanations: I’d had a bout of narcolepsy, Laura and the others had forgotten I was there, I’d wakened early in the morning and gone immediately to call them. Even though I was the victim here, I wasn’t spared the flurry of finger-wagging and concern, the awkward questions, the saga of how they’d looked all over for me. I was sorry I missed the earful they must have given Laura. At last came the hugs, the reconciliation, the café con leche. It’s strange how the butter man was wiped from my memory altogether, as if I wanted to keep him a secret even from myself, and the best way to keep a secret is to forget it, or at least act as if it’s forgotten.

![]()

A parakeet hops over to the empanada and pecks earnestly. Then there are two, then four. I have to get back for breakfast. I have to do something. Do I have to do something? I do. I want to, but I also have to. I owe it to him. I decide I’ll try to find the butter man.

First I have to go to the movie theater, which is near my house, as I’ve said. I shed my pajamas and slippers and put on a T-shirt and jeans. My mom says she thought I was staying for breakfast, and I make something up: I’d forgotten it was the last day to return a library book, so I’ll stop by now and eat when I’m back.

The theater has changed so much that I barely recognize it. I haven’t been back since the years I spent glancing around for the butter man, waiting for a wall panel to shift aside as we watched The English Patient or Kolya. The lighting makes the place look new, a far cry from the old bulbs there used to be, yellowed and sticky as caramel popcorn. The glass door doesn’t have those battered aluminum edges anymore, the soda fountain is a far more hygienic and sophisticated setup, and the cups of Neapolitan ice cream are long gone.

I approach one of the young guys in navy-blue shirts and ask for the manager, whose name I’ve memorized. He’s resistant at first, says he doesn’t want gossips snooping around this whole business. I suddenly hear myself saying in a low, steady voice, “I’m his daughter. I haven’t heard from him in eight years.” His expression changes instantly. Then he leads me to his office and explains with great caution that my alleged father was “not all there,” that he’d gotten very aggressive when asked to leave, so they had to “hand things over to the authorities.” He jots down the number of the precinct that’s handling the case and hands me the slip of paper. On my way out, one of the blue-shirted employees hands me a garbage bag filled with “his personal effects.” The guy’s shifty gaze says that he knew the butter man, too.

Then the manager asks me to follow him and leaves me with the head of security. This time the man offers no show of sympathy, nothing of the sort. As it turns out, my alleged father owes a lot of money in compensation for the damage incurred by his illicit stay behind the theater walls for all these years. The guy says threateningly that his lawyers will be taking legal action. I assure him that I’ll do everything in my power to straighten things out and pay what’s owed. I give him a false name and phone number and bolt for the door.

![]()

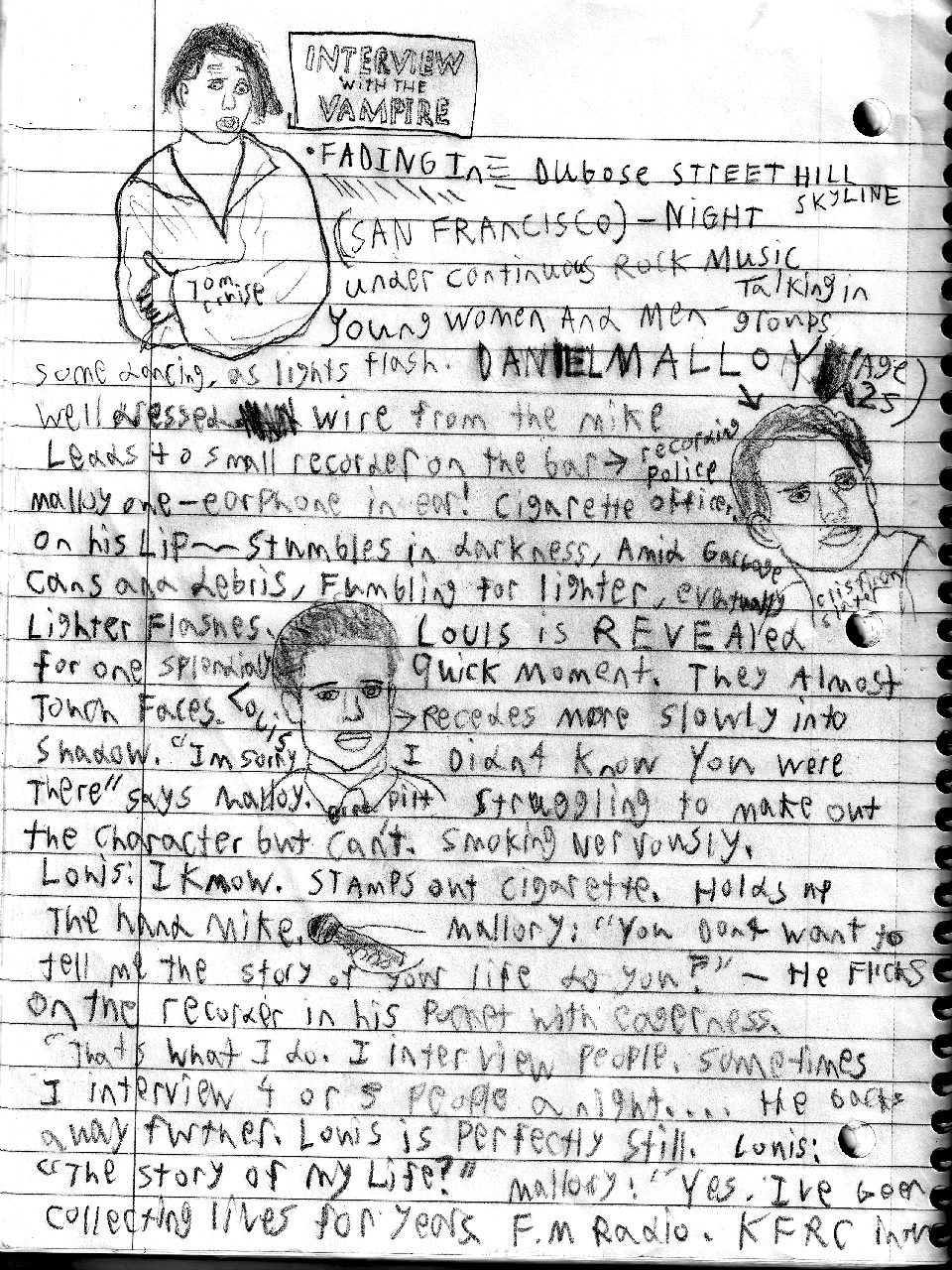

Back home, Laura’s baby wakes at the sound of the door and starts to cry. Laura peers out, furious, then steps back into the room without a word, soothing her daughter in her arms. My parents are out. I set a large pot of water on the stove for soup. Then I shut myself in my room and dump the contents of the bag onto the floor. The smell is overpowering. The butter man had hidden in there for eight years. There are photographs, newspaper clippings about movies, tons of papers, the portable radio, broken, and small shiny objects like a rhinestone earring, beads, buttons, and a little mirror with a faded photo of the actress Verónica Castro. His watch, which looks like a knickknack to me now. And the notebooks, of course. There are six of them and they’re scrawled with dense handwritten notes about movies. Anyone might think that these scribbles gave rise to the screenplay of Interview with the Vampire or Forrest Gump. He describes details, dialogues, gestures. He analyzes episodes and rewrites alternate endings, all in wild handwriting and delirious language. Suddenly I feel like I’m invading someone’s home, encroaching on his privacy. I push everything aside and go to the kitchen to season the soup. I pour it out into Tupperwares, pack the butter man’s things into a gym bag, and fill a plastic bag with the containers of food. On my way back to the precinct, I think about why on earth the butter man would have wanted to live behind a panel, next to an air vent, inside a movie theater. I wonder if they’ll let me see him, if he’ll be willing to explain, if he’ll launch into some dramatic or horrifying or delusional story. Probably not. Maybe I’ll find him so far gone that he won’t be able to speak at all.

I reach the police station. This time I tell the truth. I say I have no relationship to him and can’t pay his bail, just that I’ve come to give him his things, some food, toilet paper, shampoo. After a long wait, a woman officer takes the bags and asks if I want to go in and see him. I hesitate. Then I say no. I don’t want to. Some things are best kept secret, and the best way to keep a secret is to forget it, or at least act as if it’s forgotten. ![]()

Ave Berrera (Guadalajara, Mexico, 1980) holds a degree in Hispanic literature from the University of Guadalajara and for several years was editor in Oaxaca. She received the Sergio Galindo Award from Veracruz University for her first novel, Puertas demasiado pequeñas (A Door Too Small). She also writes short stories and has published the illustrated children’s book Una noche en el laberinto (A Night in a Labyrinth, Edebé 2014). She currently lives in Mexico City and is writing a new novel, Tratado de la vida marina (A Treatise of Marine Life), with support from the Mexican National Fund for Culture and the Arts (FONCA). Her latest novel, Restauración (Restoration), was published in 2019 in Mexico and Spain.

Robin Myers is a New York–born, Mexico City–based poet and translator. Her translations have appeared in the Kenyon Review, the Harvard Review, Two Lines, The Offing, Waxwing, Beloit Poetry Journal, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among others. In 2009, she was named a fellow of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA); in 2014, she was awarded a residency at the Banff Literary Translation Centre (BILTC); and in 2017, she was selected to participate in the feminist translation colloquium A-Fest. Recent book-length translations include Lyric Poetry Is Dead by Ezequiel Zaidenwerg, Animals at the End of the World by Gloria Susana Esquivel, Cars on Fire by Mónica Ramón Ríos, and Salt Crystals by Cristina Bendek.

Illustration: Nick Stout