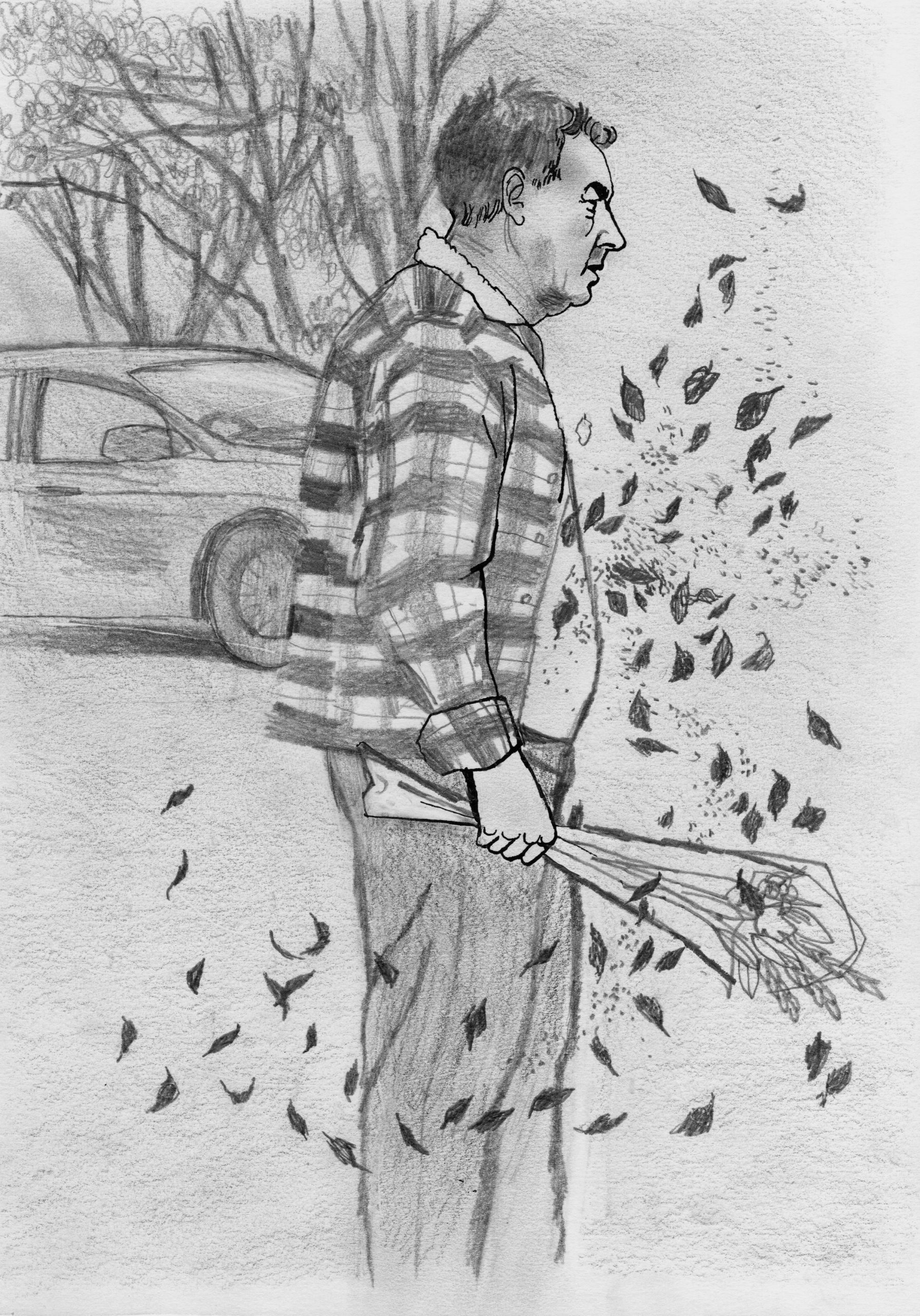

Gary put his car in park and shut off the engine. It idled for a few seconds, then was still. It reminded him of a death rattle. He grabbed the bouquet of artificial flowers and got out of the car. Slamming the door was a necessity, not an expression of his current mood. If he didn’t, the door wouldn’t close properly. The November wind swirled around him, picking up a few leaves and spinning them in a pirouette. Gary paused, watching those leaves tumble and twist. When he was a child, his grandma had said dust devils were actually people we loved who had gone on trying to pierce the veil. Back then the idea had seemed funny. An old wives’ tale from an old wife. Now, as he started for the cemetery, the notion made his stomach convulse.

The H. T. Barlow Cemetery was used by three different churches to bury their dead. Gary hadn’t been much of a churchgoer before taking his five-year fall and he hadn’t gone at all since he’d gotten out, but his mother had been a faithful congregant of the Holy Church of the Redeemer, Red Hill County, Virginia. His aunt had written him and told him that this was the place his mother had spoken of often. This cold, deserted corner of the county bordered by beech and oak trees was where she wanted to rest for eternity she said, as the lupus turned her own body against her. Gary had tried to get out on a furlough for the funeral, but when you’ve been convicted of beating a man to death over a card game, the state doesn’t see you as a viable candidate for mercy. He’d gotten parole on his manslaughter charge a year and one day after his mother had finally, mercifully, died.

His aunt told him his mother had been buried in the far corner of the cemetery, near the edge of the forest. The first time he’d come here last summer he’d searched for about an hour before he finally found it. He’d been expecting to see some kind of headstone but his daddy hadn’t gotten around to getting one yet, so the only thing that marked his mother’s final resting place was a small square aluminum sign with her last name and date of birth and death stamped into the pliable metal. A complimentary gift from the funeral home. Gary had finally saved enough money working at the fish house to put a flat granite headstone at her grave earlier this year for the anniversary of her passing. His daddy had seen him at the gas station and commented that it was a nice stone.

Gary had nodded and gotten in his car, feigning tardiness for a commitment that didn’t exist.

Brown grass crunched under his feet as he made his way to his mother’s grave. He gripped the flowers tight in his massive hand. It never got any easier coming out here. It never got any easier saying the words “my momma is dead.” When they had pronounced him guilty (not of the murder the prosecutor had wanted but of the manslaughter his state-provided attorney had pushed for with herculean effort), his daddy had been at Sailor’s getting drunk. His mother, on two canes and her face swollen and puffy from steroid injections, had screamed out to God asking why he’d let this happen to her boy.

The bailiff had shushed her, which had drawn the ire of the gallery. His mother, who had prayed for him every night, who had gone to church every Sunday until her legs stopped working, who read the book of Job for life lessons, had experienced her first crisis of faith that day. The fact that he had caved in Sully’s head with a bottle of Jack Daniel’s had done nothing to lessen her faith in his innocence. Sully was a known wife beater and womanizer and minor drug dealer. Hadn’t Gary done the world a service putting him in a hole?

Gary knew he hadn’t acted out of righteousness that night. He’d told his mother that things had just gotten out of hand, but that was unequivocally a lie. He’d gone to that game specifically to kill Sully. Nisha had confessed how she’d paid for her last hit of horse. How she and Sully had made an arrangement. From the moment the words had left her mouth, Sully Morgan was a dead man. Gary wasn’t a hardhead or a small-town gangster. He’d been a manager for the big hardware store in the next county. But he had a temper. A temper born from a crucible formed by his father’s irresponsibility and his mother’s illness. A rage lived in him that was stoked by the years of having to track down his daddy when his mother had a bad spell with her illness. Of seeing his daddy in the arms of other women while his mother needed help to the bathroom. Of watching his mother decline inch by painful inch and still calling on a God that seemed to have gone senile. When his wife had told him she’d paid Sully with her mouth, the weight of that rage was like gravity pulling down to a singularity in the black hole of his heart.

His mother’s faith in him, like her faith in the Lord, had been sadly misplaced.

Gary cut across a few graves with headstones so weathered the names had all but disappeared, when suddenly he stopped in his tracks. There was a figure standing at the foot of his mother’s grave.

He knew that figure, knew the subtle slope of its shoulders. The way the head seemed perpetually bowed and leaning to the right.

Gary took a deep breath and continued on his way. When he got to the grave he spoke to the figure in a voice that sounded alien to his own ears.

“Daddy.” Was all he said. The thin, stooped figure shrugged.

“She always wanted to go to Dover for her birthday. See a show. Play on the roulette wheel. Stay in a nice hotel. We just never had the money,” his father said.

“You mean you drank the money up,” Gary said. His daddy shrugged again.

“Yeah. I drank it up,” his daddy said.

“I’m just putting some flowers out here. You stay as long as you want,” Gary said. He squatted on his haunches and stuck the plastic stake at the bottom of the bouquet into the ground.

“It was hard watching her, watching what that shit did to her,” his daddy said.

“Not as hard as it was for her living with it,” Gary said.

“Things got really bad when you was gone. Worse than you could think,” his daddy said.

The words came out slurred. Gary had checked his watch before getting out of the car. It was half past ten in the morning. When he stood he could smell the whiskey coming off his father. A sickly sweet scent that instantly transported him back to his childhood. The smell of whiskey, the rough sandpaper of his daddy’s cheek as five-year-old Gary kissed him before going to sleep for the night. The hushed sounds of his mother and father arguing as he drifted off to sleep.

“You was treating her like shit before she got sick. Cheating on her. Stealing her money. You tell yourself whatever you want but don’t say them lies here. Not today,” Gary said. There was an extra bite in his speech that frightened him. The rage was stirring in its cage and the bars were fragile as tissue paper. He didn’t want to get into it with the old man while they stood over his mother’s body on her birthday, but the audacity it took for him to say it was hard watching her? He had more nerve than a toothache to even think that, let alone say it.

“That’s how you talk to me? I’m your daddy. You think you know everything, don’t ya? You think you know what went on between me and my wife?” his daddy said. He’d straightened to his full six-foot-three height. He was just as tall as Gary but only half as wide. Gary balled his hands into fists. Was fury the only gift his father had given him?

“Your wife? She was my momma! And you treated her like you was ashamed of her!” Gary said. He squeezed his fists so tight his knuckles cracked. His father lowered his head again. The momentary strength of character he’d exhibited had ebbed.

“I was never ashamed of her. You don’t remember how things was before she got sick. I loved her, boy. Your momma was the woman I wanted to have babies with from the first day I saw her. But she had a devil in her. You don’t remember her throwing lye at me when I came home late from Timmy’s birthday party? Or the time she put her foot on top of mine on the gas pedal when we was coming home from the store? Or how about when she slapped me so hard she loosened my tooth? That was why I used to drink. That was why I went out. I loved her but she could flip on you like a switch went off in her head. Where you think you get your temper from? Huh? You ever see me put my hands on her? Ever? Then she got sick and that devil inside her got quiet. She turned all that energy on the church. But by that time, I had crawled in a bottle I couldn’t get out of. She was my wife long before she was your momma. I knew her like you couldn’t. Child shouldn’t have to know their momma that way,” his daddy said.

Gary unfurled his fists. What his old man was saying was obviously a lie. Wasn’t it? He’d never heard his mother say a cross word to his daddy. True, she had said harsh things about his daddy, but that was after he’d been gone all weekend and come back smelling like a brewery. His daddy was lying.

He had to be.

“I ain’t come here to argue with you,” Gary said. He wiped his hands on his jacket and headed for his car.

“I loved her, Gary. If I didn’t love her, how could I have done what she asked me to do?” his daddy murmured.

Gary stopped. He turned and faced his daddy.

“What are you talking about?”

“You wasn’t there. They’d locked you up. You didn’t see the bedsores. Didn’t see the way her legs twisted like pretzels. How the steroids swole her up like a piece of sausage. I didn’t want to do it, I told her. What was I supposed to do without her? How was I supposed to go on without her, knowing what I’d done?” his daddy sobbed.

The sound of a rabbit in a snare trap.

“What are you saying?” Gary asked. His voice was baby-skin soft.

“She asked me to do it. She couldn’t do it herself. Her hands had stopped working. They buried her out here and I just wanted to get in the casket with her. I didn’t want to do it!” his daddy moaned.

Gary seemed to be watching himself from a seat in a theater. Watching as he walked over to his daddy. Watching as he put his hands around the old man’s throat.

“WHAT DID YOU DO?” he screamed. The echo reverberated off the trees and the tombstones.

“She wanted to be done with it,” his daddy gasped.

Gary saw that his daddy was crying.

He felt tears on his own face as well.

The wind blew harsh and cold through the garden of stone in which they stood. Like the breath of an ice god come down from a mountain, snatching away the warmth of Gary’s body even as he squeezed his hands around his daddy’s neck.

Even as he saw his father’s eyes roll back in his head.

Heard the rattle in his throat. ![]()

S. A. Cosby is a best-selling, award-winning author from Gloucester, Virginia. His books include Blacktop Wasteland and Razorblade Tears.

Illustration: Lucinda Rogers