Those were the nights of the first great snowfall in Buenos Aires. An unanticipated, white fury that turned a few streets into low- or moderate-risk slopes. Everyone bought skis and wool hats, and kiosks popped up on corners where vendors sold hot chocolate and roasted chestnuts in pans misshapen by dents and desperation. Everyone said that yes, that now, at last, we were an indivisible part of Europe. Some people froze to death and said nothing.

Those were the nights, the first nights of the Third Millennium.

And the nights were no longer black. Now the nights were gray.

The tyranny of progress and the dictatorship of neon had eradicated the idea of darkness forever, and everyone slept with sleeping masks on and the blinds drawn and circled the wagons in the event of the unsurprising eventuality of a surprise attack.

But there are several ways to start this story. One way—as we’ve seen—is to hold aloft the beams of Universal History, to settle for the deceptive spectacularity of traveling without moving via email and the information superhighway, to succumb to the idea of being everywhere when really we’re nowhere.

The other way—the one that most interests me—is to lean on a private history. A minor history and, as such, a graspable history.

Those were the nights when a man couldn’t stop thinking about the name of a woman.

![]()

Let me explain: when we think that everything has come to an end, the dead live on in the most unsuspected places, almost always in close proximity. In the brief sigh of silence between one word and the next, for example.

Like this:

What (Diana) are (Diana) your (Diana) plans (Diana) for (Diana) next (Diana) Monday (Diana) night? someone asks the man who can’t stop thinking about the name of a woman.

Diana is dead. Diana died. Diana remains dead but Diana still breathes in the five letters of her name. The word Diana like a microorganism, invisible yet omnipresent, in the idea of that party he assumes they’re about to invite him to. He’s already grown accustomed to the well-meaning inefficiency of these lifesavers. Then the worn-out lines of no, I don’t have anyone to watch my daughter, and the telephonic smile of but why don’t you bring her along and we’ll put on a movie in the bedroom and she’ll be all set, and the idea that if he doesn’t say yes at least once for every nine times he says no, things could get complicated. He’ll really start to believe that Diana isn’t exactly dead, that Diana is still alive, and that he—more and more like a dead man than a living man—is breathing for her.

A dead man who takes a breath.

A dead man who takes a breath and this time says yes.

A dead man named Daniel.

A dead man who is a father and a widower and has a daughter who is alive, a daughter named Hilda.

![]()

At first, we resist with all our might and all our terror coming anywhere near a dead body. We prefer not to see it, “to remember them as they were when alive and blah blah blah.” Then something strange happens: all it takes is a glimpse out of the corner of our eye, an involuntary intuition, to realize that from now on we’ll never stop seeing it.

It’s then that we lean over the rim of the coffin like a cliff’s edge and look down, defying the vertigo of our own inevitable future.

It is then that, behind the inanity of “She looks like she’s sleeping,” we approach the certainty of “She’s dead, she’s other, she’s the same, and she can’t recognize me anymore . . . this dead woman has forgotten me forever.”

In any case, nobody in their right mind who saw Diana’s body could have said, “It looks like she’s sleeping.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

![]()

Now, on my screen, Daniel enters Hilda’s room and tells her to wake up, that they’re going to a party. Hilda was sleeping, it’s eleven o’clock at night. Hilda opens her eyes and realizes that she’s back on Earth, that she has a mission to carry out. Hilda gets dressed slowly. Daniel sits on her bed and watches her put on her pretty little dress and he lights a cigarette and keeps watching her, wondering why she hadn’t died instead of Diana, then immediately thinks that it’s not okay for him to think such things and averts his eyes.

“I don’t imagine that you’re going to bring that grubby little pillow with you,” Daniel says to Hilda without looking at her.

The smoke of those words ascends to the ceiling and hovers there.

Hilda doesn’t respond. Hilda knows from experience that it’s better not to respond to her father when he’s about to leave for a party, and she grabs her pillow and squeezes it tightly against her little chest and leaves the room, followed by Daniel.

Walking from the door, Hilda pauses for a few seconds in front of the television. The man—that man with the red eyes and messy hair and twisted tie who is on all the channels all the time—says something about “stratosphere,” about “rockets,” about “Argentine interplanetary exploration,” about “the cosmic fatherland.” And although Hilda doesn’t watch much television—Hilda never refers to the television as “the TV”—something makes Hilda want to stay and listen to him.

Maybe the man will say something about Urkh 24, Hilda thinks.

Hilda’s convinced that she wasn’t born here, that Diana and Daniel aren’t her real parents, that she’s part of the advance party from a planet that doesn’t appear on maps or through telescopes.

A planet called Urkh 24.

A planet where Hilda is beautiful.

![]()

Hilda’s room is decorated with posters of galaxies and constellations and a mobile with all the planets of the solar system and a bed in the shape of a space rocket. Hilda is eight and—Daniel is not entirely sure why—Hilda is obsessed with the idea of the immensity of the universe and its multiplicity of possibilities and with the idea of inherent limitations and of one’s own modest glow being nothing compared to the flashing brilliance of light years.

When anybody asks Hilda with a mellifluous voice what she wants to be when she grows up, Hilda takes a deep breath and answers without hesitation, with a furrowed brow and the speed of someone pronouncing a really long word and trying not to fall into the hole of its vowels or to get snagged on the thorns of its consonants.

“When I grow up, I want to be the person who discovers irrefutable proof of intelligent life on other planets,” Hilda says.

And the person who asked the question says, “That’s cute,” when really they think, “That’s strange.”

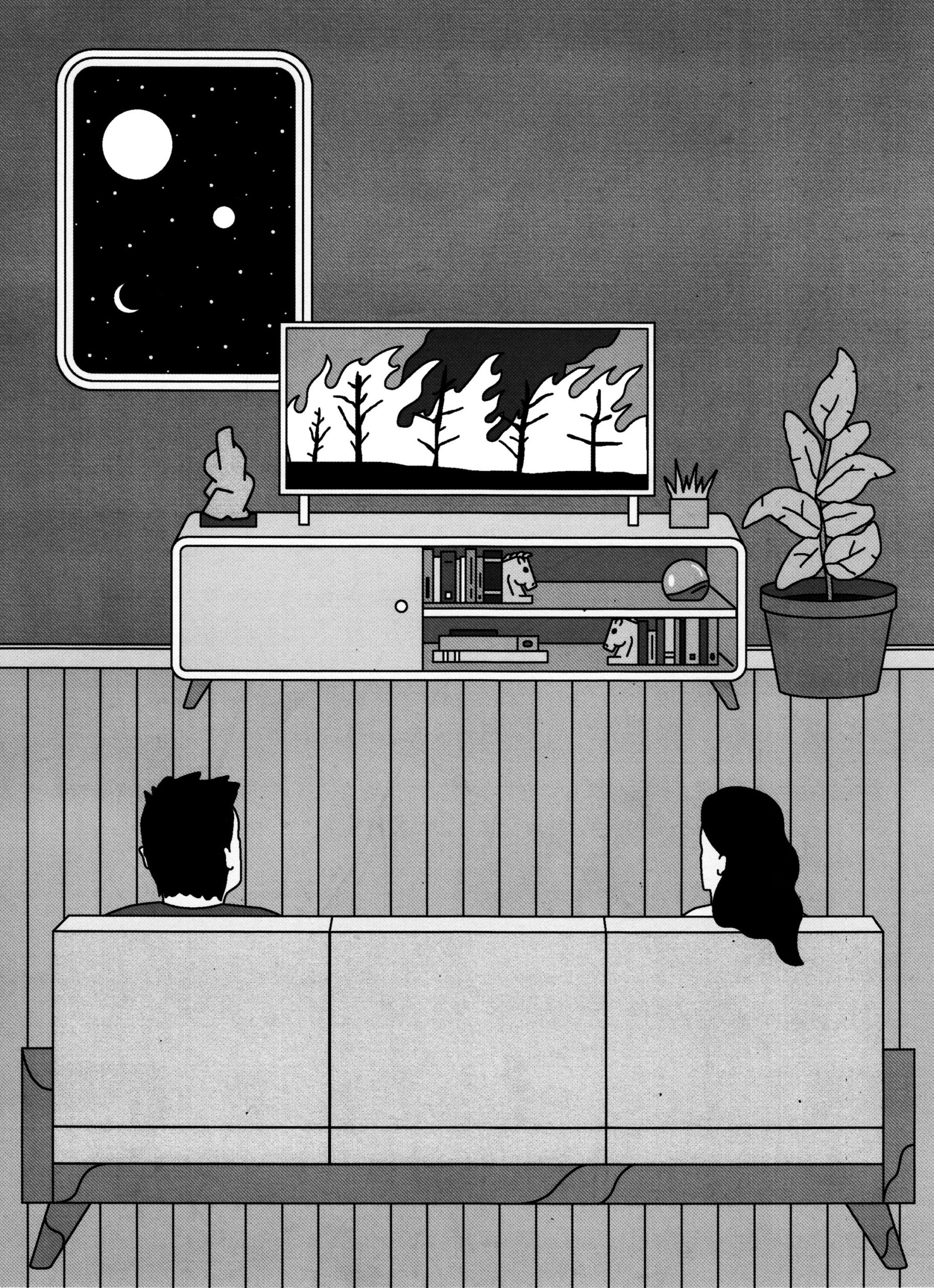

Diana told me all of this, and the truth is that, yes, Hilda is a really strange kid. Maybe it has something to do with the way Hilda was conceived. On a night when Diana and Daniel were watching a documentary on TV about the planet’s slow and inexorable overheating. One of those apocalyptic documentaries where a grave voice applies just the right words to images of forest fires, earthquakes, floods.

That night, Diana and Daniel decided they weren’t going to have kids, that it made no sense to bring a new life to this doomed planet, and one thing led to another and they switched off the TV, made love, and switched on Hilda.

Hilda was born two months premature, dead.

Hilda was born and didn’t cry and hasn’t cried since.

Hilda was born with the umbilical cord wrapped round her neck and nobody really knows how she came back to life, and even then, her chances of survival were exceedingly slim.

That’s why they named her Hilda. An old name. Out of superstition.

“We gave her that name because they told us her chances weren’t good, that she would only be on the planet a short time. We named her Hilda so she would seem larger, sturdier, and stronger,” Diana and Daniel repeated over and over, as if apologizing.

Hilda survived. Hilda sleeps among planets and shooting stars. Hilda wakes up in the night screaming, not because her mother is dead, but because of the uninterrupted expansion of the diameter of the black hole in the ozone.

![]()

Who does Hilda look like? One thing’s for sure: Hilda looks nothing like Diana or Daniel.

Even before they decided to work in advertising, Diana and Daniel always looked like two fashion-show fugitives, two models who grew weary of that whole circus and went strolling off down the runway. Diana told me how, on the street, people turned to watch them walk, and some even took their pictures, mistaking them for who knows which demigods. Japanese tourists, always. Here and in Europe and in the United States. Obviously they just laughed it off. And kept on walking. All they had to do was smile and mountains would move, as if they lived in constant rear projection, as if someone were paying an invisible creature to swap the landscapes behind them, across a backdrop bluer than the bluest of skies. Maybe there was something almost obscene—almost pornographic—in the combination of their respective beauties, added to the now almost-legendary happiness they exuded together. Diana and Daniel were an archetypal couple. The exception that proves the rule. A couple too beautiful to be real and, as such, too enviable. Maybe the true nature of their tragedy lies in the fact that Diana and Daniel decided to take the easiest of streets: Diana and Daniel ended up being just what they appeared to be. Argentine models. And so more than one of their friends breathed easy when Hilda was born. Hilda as the irrefutable proof that not everything is perfect. Almost all of Diana and Daniel’s friends were or had been Argentine models or were on the point of becoming Argentine models. I was an Argentine model too.

![]()

I say model and immediately jump back and stick in an Argentine because it seems more definitive, it seems right. An Argentine model is one who—between one stroll and the next along the catwalk—won’t hesitate to announce that he recently broke into film, when the truth is he played the part of an airline pilot in one of those brief informational videos that precede the takeoff of an airplane and the beginning of a journey and that are intended to demonstrate for the passengers the distracting inanity of the flotation device under their seat in the event that it all comes crashing down. We were all Argentine models; which is to say, models who worked only in Argentina, models who weren’t known elsewhere.

If there is one distinctive trait that accompanies all the weak people of this world, it is their insistence on, time and again, doing that which they know will turn out more or less well for them. Argentine models are, accordingly, weak people, and I was a weak person. I was one of those typical forty-something men, ideal for cigarette ads aboard a sailboat or automobile ads beside a polo pitch. An impossible-to-export national product. I suppose Diana and Daniel might’ve had a chance abroad if they’d made it out in time, if Hilda hadn’t been born.

The only Argentine model who’s not Argentine is Piva and she’s dead now. Piva died of a new disease, a rare disease, and—before the end—Piva stipulated that her wake should be a gigantic photographic production. No coffin. Piva standing, suspended by an invisible mechanism that, every five minutes, made her move ever so slightly, defying the immanence of rigor mortis. Guests and flashes and multiple TV channels, Helmut Newton taking the photos. It’s all there, on the cover of Vanity Fair.

But Piva was nothing more than the exception that proves the rule in a country where Hurricane Anorexia blew powerfully and Cyclone Bulimia tactlessly lashed the figures and waistlines of languid virgins desperate for quick and easy fame. A country where so many people had renounced the gift of a smile because it hurt the stitches of their latest but never last cosmetic surgery.

At some point I read something a professional photographer said. A famous photographer; I don’t remember her name but I do remember that she started out doing fashion shoots in the fifties and wound up following freaks and aberrations of nature through New York nights. A photographer who ended up exposing the negative of her own life by cutting open her veins. That photographer said that a photograph is the secret of a secret, that a good photograph is a photograph that could tell its own story.

If this is true, our photographs—the photographs of Argentine models—don’t work as stories, don’t conceal stories.

Everything is out in the open.

In black and white or in color.

It doesn’t matter.

Nothing.

![]()

This is also, in a way, a love story.

All love stories remind me of my mother’s story.

My mother was another of beauty’s countless victims. A provincial beauty queen who left my father and fled with me to the capital to seek her fortune and ended up finding it serving glasses of vodka to a popular showman who would slug back a long swallow and exclaim, “But oh how tasty is the agüita today!”

My mother always told me that there were two forms of love: the love of those who took each other by the hand and began the arduous climb up the mountain, and the love of those who took each other by the hand and threw themselves down the mountain. When I asked her if there might not exist another possibility, my mother—whose only responsibility as Chica Agüita was to pretend to remind the host what brand of water was sponsoring the show and who ended up diving off the highest diving board into an empty swimming pool—gave me a pill-saddened smile and blubbered, “Of course: blowing the whole goddamn mountain up with a good charge of TNT and blasting all of it to the most reverential of hells.”

I wonder where on the mountain Diana and Daniel met each other.

I wonder if the fact that Diana and Daniel had cheated the system, that all of it had begun with them flying over the mountain in an airplane, might not have exerted some influence on the unfolding of future events.

Diana and Daniel met by accident, literally.

Diana and Daniel met on an airplane that was crossing the Atlantic. They were talking about how irrational it was that airplanes flew, that airplanes could fly, when—as if that jumbo jet had heard them talking and what they had said sent it plummeting into the deepest of depressions—events precipitated. The plane went into a nosedive and the luminous signs had the horrendous taste to inform the passengers that it wouldn’t be a bad idea—just in case, in case God happened to exist—to perform the farce of fastening their seatbelts and extinguishing their cigarettes. The whole thing couldn’t have lasted more than thirty seconds, the plane leveled off as if waking up from a nightmare, and the voice of the pilot announced with a cowboy accent that “we almost bought the farm in the sky, wooooweeeee!!!” Diana and Daniel didn’t hear him. Diana and Daniel were under a blanket making love like cats in heat, sweating out the terror of imminent death, thinking that nothing happened by chance and that there would be no need to call the flight attendant to ask her to bring them some simultaneous and multiple orgasms.

![]()

Once, in Japan—they had traveled there to film a cigarette commercial, one more in a series that showed them smoking the world over, life is smoke and geography too—Diana and Daniel stopped in front of one of the latest attractions in Tokyo’s colossal video arcades.

This was during the peak of the Pachinko Fever, which drove people to play and play and keep on playing.

A machine called Love Love Simulation.

A device designed to predict what the child of a given couple would look like. Five dollars into the slot and the device recorded the faces of the man and woman and then combined them into a perfect digital prediction. Laser chromosomes. Diana told me about it in a postcard. If you were single, the machine also offered potential candidates or—if you preferred—it combined your face with flowers, orangutans, or famous paintings. Diana and Daniel uploaded their respective faces and—Diana told me—the end product, the hypothetical child, was so beautiful that the machine recommended viewing it with half-closed eyes, from behind dark shades, and at a distance, just in case. An angel of light, a new nova.

Another demonstration that machines are not yet on a level with humans. Machines make mistakes, and if you were to ask me who Hilda looks like—if there existed a machine that traveled the inverse path from Love Love Simulation, a mechanical invention that traced parents instead of children—I wouldn’t hesitate to tell you that Hilda looks like, that Hilda comes from, that Hilda is the fruit of the improbable marriage of Ernest Borgnine and Edward G. Robinson.

![]()

Hilda is ugly.

Hilda is ugly and lightning strikes the surface of the planet about one hundred times per second and the temperature of lightning is five times that of the temperature on the surface of the sun. Thirty thousand degrees Celsius.

Hilda is very ugly.

![]()

The first person to tell Hilda a story about Urkh 24 was Diana. She told her those stories so that she would fall asleep, so that she would travel through space, so that, from a young age, she would assimilate the possibility of better worlds.

As time passed, Diana’s stories changed. Diana stopped describing the natural wonders of that planet and focused on certain details. “On Urkh 24, Hilda would be the most beautiful of all the children,” Diana told her one night before leaving for a party of models. Daniel overheard her while tying his tie and it was all he could do not to strangle Diana, not to strangle himself. Later, in the elevator, they fought about whatever other thing while Hilda was left alone in the dark.

Hilda lying in bed saying things like “Planet Earth is 4,600,000,000 years old, it contains ninety-four natural chemical elements, and it is believed to have been home to life for three or four billion years. Modern man has only been around for 10,000 years . . .”

Hilda knows all these things because she read them on the box of the planet Earth–shaped pillow that I gave her on her fifth birthday. I was impelled to buy it by a strange feeling that struck me as interesting to respect. That night I gave it to Diana so she could give it to Hilda.

The pillow was North American, and so all the cosmic data was in miles and not kilometers, which is why Hilda is now having problems in school.

Hilda has no interest in kilometers or in the Hispanic acceptation of billions versus the Anglo acceptation of billions.

Hilda began to pray.

Hilda learned to believe in something, from the box of an imported pillow.

Hilda prays every night to the Great Hierarchs of Urkh 24.

Hilda will never betray her pillow.

Hilda takes her planet pillow with her everywhere, even though, with the passing years and fading colors, it gets increasingly difficult to identify the silhouettes of the continents.

Better, Hilda thinks, my pillow isn’t Earth anymore; now my pillow is Urkh 24.

I remember that Hilda opened the package and hugged the pillow and gave me a gap-toothed smile, and for an instant, Hilda seemed almost beautiful.

![]()

Daniel thought it was a party for models, but it wasn’t.

Daniel remembers that models don’t invite him to parties for models anymore. Daniel is too unstable these days, he stumbles, comes out blurry in photographs, wears wrinkled clothes. Daniel damages the product image.

This is a different kind of party and Daniel wonders what he’s doing here. Daniel can’t remember who invited him. Almost everyone is younger than him. He doesn’t know any of them. He sees someone he recognizes. Out on the balcony. That musician. The one who married one of Diana’s model friends who lost her mind or attempted suicide or got committed to an insane asylum. Something to do with a baby. Daniel isn’t sure and doesn’t want to be. The man looks at Daniel and Daniel looks at the man—“Federico,” he thinks, “the man’s name is Federico something”—and the two of them take the measure of each other, as if wanting to determine who had the greater tragedy, whose was better and whose was bigger. They wave to each other across the living room, from one point to the other, but neither of them makes any effort to meet in the middle. That would be too much bad karma coming together in one place. It would be dangerous, and after all, identical polarities repel.

Daniel is a widower now.

Widowhood is like having moved to a foreign country without even realizing it, like speaking a new language learned in one night using one of those audiovisual methods, like the preview of the new European collections. That’s the spring line and this is the fall.

Someone once told me that to be widowed was like waking up underwater and discovering that your lungs had been removed during the night. In that sense, models are lucky. Models learn to breathe underwater. Models are accustomed to being captured in the flesh on film, to being seen and appreciated like fish floating in an aquarium.

I think about how Daniel thinks about Cary Grant, about James Stewart, about celluloid widowers. Daniel watches those black-and-white films in which the figure of the widower is vaguely romantic and even funny and, of course, coveted by all the young girls at the party. Daniel never watches those films all the way to the end, because the idea of discovering that they have happy endings makes him panic, that then he too might find himself obliged to fight for the possibility of a happy ending, or that, even worse, life goes on.

So Daniel turns off the TV and concentrates on the glossy pages of Diana’s book. Big photographs, eyes looking you in the eyes. Diana getting out of a limousine, Diana climbing a painter’s ladder, Diana walking out of the sea, Diana slipping into a bathtub. Daniel is surprised to discover that photographs die too. Photographs die when the person who appears in them dies. Then the photographs change sign: before, the photographs were the immovable evidence of a living being, and now, all of a sudden, they are transformed into the photographs of a dead person when they were alive. Now he discovers that the photographs of Diana are more alive than Diana. Sometimes, if he stares at them for hours, he could even swear that those photographs move, that Diana winks at him in those photographs.

Daniel laughs too hard and there are nights when he wakes up Hilda with his laughter. Daniel’s laughter is one long and piercing and unbroken note. Daniel laughs the same way that Chinese people weep.

![]()

Daniel gave away all of Diana’s clothing. He donated it, wondering who could possibly find anything practical in all of that. There was nothing more useless than excessively beautiful clothing specially and beautifully designed for an excessively beautiful woman. Not even another excessively beautiful woman could get any use out of it.

The only thing Daniel kept was Diana’s toothbrush.

Portrait of a man brushing his teeth with his dead wife’s toothbrush.

Every night, right around this time.

![]()

The night that Diana died, Daniel got home late. Hilda was at a friend’s house or an aunt’s house or shut in her room looking up at the sky through her telescope. There was a message on the answering machine. Daniel was returning from identifying Diana’s body at the morgue, and then, standing in front of the device’s little blinking light, Daniel identified Diana’s voice. Diana’s voice saying: “Problems at the channel. Some videos got erased. We have to rerecord an entire episode. I don’t know what time I’ll be home.”

“Problems,” Daniel thought. And then he thought “Erased” and “I don’t know what time I’ll be home.”

Daniel listened to the message multiple times. Too many. “It’s true, ghosts do exist,” Daniel thought as he listened to Diana’s voice lying to him over and over again.

![]()

“All morgues are the same,” Daniel thought. Of course, he wasn’t sure about that, but he was sure that he thought that. In other words, that’s the kind of thing you think when you go into a morgue. Just the fact of thinking it—of discovering that he could still think—calmed him a little. Thus, the circular reasoning—you climb up onto the diving board of a cold and impersonal abstraction so you can dive better, from on high, into the breaking waves of pain—goes like this:

1. I’m in a morgue.

2. I know all morgues.

3. There’s no point in ever going into another morgue for the rest of my life.

4. This is the worst thing that’ll ever happen to me until I die, until they bring me to a morgue.

5. Diana.

Then, all police officers are the same and all morgue employees are the same. They all smell of formaldehyde, of cold, of heavy doors and metal gurneys with a drain in the center. First, Daniel sees the body of an old woman someone left out in the corridor. He looks at it hard, stares at it, with all of his eyes, thinking that if he looks at another dead body first—any dead body—the sight of a dead Diana won’t be so horrible and devastating. The employee says something to him, shows him a purse, and yes, it’s Diana’s purse, so why don’t I just go home now, Daniel thinks. He remembers having read somewhere that there are already televisual morgues, dead bodies on closed circuit. You tune in a dead body. You see a dead body on a television—brightness, color, freeze—and wonder when it will cut to commercial. Daniel and the employee descend in an elevator, walk down a corridor, enter a room. Above the door, in Latin, in capital letters, it reads: Let words fall silent, let laughter flee, herein the dead are pleased to help the living.

One of the employees tells Daniel that Diana had donated her organs. Daniel says he didn’t know. The employee gives him a form to sign and warns him about something, explains something to him.

Later—in the middle of a too-long fashion show where he came to a stop at one end of the runway and began to talk and talk and not stop talking even when several other models came out and dragged him back to the dressing rooms—Daniel would think that nothing mattered anymore, that everything was fine, that all sense of ridiculousness was lost on you after you threw yourself down onto a dead body to kiss it and beg it to speak to you even while, somewhere inside, you know that you’re kissing that dead body just so you wouldn’t have to wonder, later on, why you hadn’t kissed it.

Daniel feels embarrassed to be kissing a dead body only identifiable by a ring and the most famous pair of legs in the country.

Then, when Daniel had calmed down, they brought him clean clothes and took him to a bathroom so he could wash off the blood.

Then they gave him a warm and cheap whiskey.

Then they asked him if he could identify the man who came in with the deceased.

Then they showed him my body.

![]()

I never take my documents when I go out.

I always thought it brought bad luck to go out with documents, to be easily identifiable, to be easy.

Ha.

In the morgue, Daniel got my last name right but messed up my first name, and—when it comes to the most pertinent identifications and authenticating credentials—you would all do well to ask yourselves why I’m the one telling this story. Why not Diana? Where is she, anyway?

The answer is not simple and I haven’t been here long. I’ll just say that she’s in that place that we, from there, when we’re alive, don’t hesitate to call The Beyond, and that, since I’ve been here, I’ve been quick to rename The Abroad.

One of Diana’s many aristocratic aunts claimed that dying was a gesture of profoundly poor taste; as such, whenever a family member breathed his or her last breath, she didn’t wait to inform all her relatives—as if the obituaries in La Nación were nothing but an inopportune paper-and-ink mirage—that that person had “gone Abroad, that he’s off traveling, we don’t know when he’ll come home.” Diana’s aunt said “Abroad” as if it were capitalized, as if it referred to the most expensive and exclusive hotel of the Côte Bleue.

That name and idea, it didn’t take me long to discover, fit this place perfectly. A vague sense of ceaseless transit, a mix-up involving a suitcase with no space left on it to tattoo a new sticker with the name of some exotic city, a feverish customs experience, and that smell of ozone that tickles the nose and that you only breathe at airports, on docks, at train stations, and, yes, in cemeteries.

The Abroad is not exempt from certain bureaucratic matters, of course. Descriptions of physical order are not the most useful when it comes to explaining the void where I now float; but it wouldn’t go too far, shortening the distances, to compare it to certain office buildings with floors divided into cubicles subdivided into smaller cubicles.

I am in one of them.

I have a chair, a desk, and a television. Nothing out of this world, the television. I’ve seen better and more modern ones in Buenos Aires. The Abroad or The Beyond, as all of you prefer to call it, is slightly behind the times.

On the television I watch Hilda and Daniel and Daniel with Hilda. I suppose that Diana is in another cubicle. Sometimes I think I hear the white whisper of other televisions, of other shows, in the air. I haven’t seen Diana since the night of the accident. Maybe her absence has to do with the damage done to her body and the fact that she took almost half an hour to die.

Maybe Diana has been rerouted to some kind area for making repairs.

Maybe they’re doing her makeup.

Maybe I’ll see her again one of these days.

I, on the other hand, didn’t suffer at all, and when it came to identifying my body, Daniel had no issue placing me, other than the one aforementioned error. I easily fell into the stupid category of “he looks like he’s sleeping,” in the lineup of good-looking corpses. Just the trail of Diana’s fingernails across my left cheek.

I ceased to exist in the time it takes to read a haiku, head twisting impossibly, neck breaking like a branch.

Maybe it has fallen on me to tell the story because I always wanted to be a writer and never wanted to be a model, but, as you know, pictures pay far better than letters.

Maybe this is my postmortem prize, my slice of paradise—the opportunity to tell a story. Or maybe an indecipherable code of ethics and good practice determines that the dead lover of a dead mother is obliged to watch over the surviving daughter for all eternity.

Maybe I’ve become something like Hilda’s guardian angel.

![]()

Maybe Diana’s absence is intrinsically linked to the fact that it was her fault that we died. She was driving the car. She was swerving all over the place and kept taking a tiny silver flask out of her purse and sticking it up her nose while howling a formless song.

(I think about Daniel and think about how Daniel couldn’t have helped thinking, every time that Diana spiraled into another of her increasingly frequent histrionic excesses, about what Diana would be like in twenty or thirty years. It frightened Daniel a little to imagine it; but it’s true that Daniel had always been one of those people who are overly concerned with epilogues, while I, on the other hand, never projected myself beyond chapter one or two of my life. For me, the overrated idea of the future always presented like one of those animals everyone thinks is soft and cuddly until they come up to lick your hand or face and then gross! The future is a guinea pig in the same way that we’re all the guinea pigs of the future. Now, none of that matters, now everything is undefined present.)

Diana was driving with one hand, using the other to stick that little flask up her nose and inhale deeply. At some point in the night, we were stopped by a police officer who recognized Diana and asked her for an autograph for his wife. Diana had gotten a minor role as Ani, the young hysterical mother of Tony, a young autistic model on a TV show called Beataminas. Diana opened a folder and took out a copy of that photograph in which she appears almost naked and scrawled her signature across it, as if wanting to cross herself out forever, and she promised the police officer that she would drive more slowly and then floored it, accelerating away at top speed.

Then, to distract her, thinking it would help—I was wrong—I told her stories about Piva.

Diana wanted to be like Piva, and I told her stories about Piva every time I felt her start to lose control and take too-tight curves at too-high speeds. I told her how Piva had been discovered teaching swimming classes to five-year-olds and how she came to shoot with a maudit film director named Lyndon Bells, a man who had managed to finish and debut a masterpiece back in the thirties or something like that, Amo del mundo, and who from then on devoted himself solely to unfinished films. As time passed, many of them were assembled by film-archive rats, which gave them the prestigious look of involuntary documentaries, of successful chronicles of cyclical failure.

In one of them—in one of the most famous scenes from another aborted project whose working title had been F for Fashion—there appears an already legendary close-up of Piva that managed to consecrate her as a great actress even though she never stood in front of a camera ever again. In the scene, a whirlwind of emotions seems to lash her perfect and changeable face: lust melts into the surprise of fright and then bursts into indignation and tears. More monographs have been written on those fifty seconds of celluloid than on black holes or Giorgione’s The Tempest. I told Diana how Lyndon Bells’s trick for achieving that miracle—like almost all tricks behind all miracles—was banal and even vulgar: without Piva knowing, Lyndon Bells sent one of his assistants to grab her ass while they were filming. Piva told me about it one night in bed, I told Diana in the car. I laughed. Diana laughed a little, she laughed without laughter, she laughed as if she thought I were laughing at her. Then, at some point along the route, Diana began to scream like a madwoman and to hit me and the next thing I remember is the car crashing into the back of a truck full to bursting with black-and-white cows.

The night filled with mooing.

Argentine meat for export.

Very appropriate.

![]()

Obviously Diana wasn’t in love with me at that time or anytime. Nothing further from the truth. I wasn’t in love with her either; but there is something in the glamorous sordidness of our profession that prevents us from denying the bodily needs of one of our female colleagues. It would be unprofessional because we are our bodies.

If you were to ask me—in light of the impossibility of asking her—I wouldn’t hesitate to tell you that Diana loved Daniel or, at least, that she loved the idea of loving Daniel. I, like so many others, was nothing but a shadow for Diana. I had the irresistible appeal of being older than her and, as such, safe. I was one of the older men that Diana slept with to keep from falling. Black mirrors, convenient and interchangeable refracting surfaces, alternative possibilities, Love Love Simulation.

If you were to ask me again, I would find myself obliged to tell you that Diana succumbed first to the allure of a double life and then—almost right away—to the panic of discovering that being someone else didn’t exclude her from the generalities of the situation and the obligations implicit in the matter. That other person that she had become was also the owner of her corresponding quota of frustrations and fears. And so Diana ended up suffering doubly, and too much has been said and written about the terrible fall of models. The dark arc of physical decadence invariably linked to decadence in all orders of life. The stigma of having worked as a beautiful person and all of that. My mother put it better than anyone. My mother said incredibly intelligent things without even realizing it. My mother was the closest thing to a hypothetical Zen monk who thinks that the I Ching is a dish of Chinese food. My mother once told me that “the bad thing about youth is that it grows old.” But if you insist, I think that the horror of Diana’s life lay elsewhere and was, as such, far more horrible and personal and difficult to control and easy to accelerate away from at top speed.

I think Diana never got over having an ugly daughter.

![]()

Maybe Diana is somewhat redeemed by the fact that the last word she spoke—I was the only one to hear it; I was there, dead and floating amid the flashing red lights and the sirens and the static of walkie-talkies and the first snowflakes—was her daughter’s name.

“Hilda,” Diana said.

And it began to snow and Diana died while everyone looked up at the sky, incredulous, to see who was the joker throwing fake snow down with a fire extinguisher.

Diana said “Hilda” one more time. Diana said “Hilda” and died before her daughter, who, supposedly, was going to die before any of us.

Then, as the medics and police officers fantasized about having a snowball fight, someone started up one of those ear-splitting saws for cutting steel and began the slow and difficult process of extracting our empty bodies.

![]()

Nobody knew the truth. Actually, a few people knew the truth, but they decided not to say anything. To hide the evidence. An oath of silence. To cover up for us. To let us be lost and let the snow hide us forever. Everything looks better draped in snow, as if it were more pure and clean and Christmassy. To ruin the love story between Diana and Daniel, to tell it from that perspective, to dare to come to grips with what had happened, was to ruin the two of them somehow. To deny any possibility that love between Argentine models could exist, that love between any two human beings was even somewhat unrealistic. And so the love story of Diana and Daniel grew and kept growing until it acquired superhuman, mythic proportions. Even Daniel—who thought about nothing but getting a divorce, about taking the air out of the golden couple forever, about reducing the whole thing to levels of nicotine and the insufferable stench of cigarettes burned down to the filter—ended up believing it. I don’t exist. I never existed and Diana died at the hands of a drunk driver.

Daniel told Hilda that that man is in prison now and that she has nothing to fear because he’ll never be let out. Sometimes, Daniel forgets what he has told her and tells Hilda that the drunk driver also died in the crash. It doesn’t matter.

Details.

Daniel prefers to focus on the figure of Diana. He practices every night, and—he calculates—it won’t be long before he gets to do the morgue scene over. In the new version—in the morgue, on the gurney—Diana is more beautiful than ever and even seems to smile at him, and he just plants a brief and elegant kiss on her mysteriously warm forehead.

When it comes to love, death always immortalizes. Romeo and Juliet and Shakespeare know it better than anyone, and—having come this far—I can’t help but acknowledge my own limitations as an effective storyteller, as well as the naive blunder of whoever conferred on me such a responsibility. My description of the love between Diana and Daniel arouses, no doubt, the same suspicions as that meteorite tattooed with fossilized microorganisms trying to convince someone that once upon a time there had been life on Mars. I guess this story would work better if I concerned myself—if I spent hours of programming or pages in a book—with transforming Diana and Daniel’s marriage into something epic, into an intimidating and perfect feat of romantic engineering. Tighten the screws, put the engines in drive, earn the respectful awe of the spectator, and only then, deliver the low blow of my presence and the collapse of the farce.

I’m sorry, I’m no good at such things, and if there’s one thing I always took issue with in narrative structures and fashion shows, it was the precision of the dramatic tempo, the ability to maintain a rhythm and to change it at will whenever the plot required, the eternal consideration for the viewer and the constant fear of losing him or her forever. The happy ending and the applause and the flashes and the finale of a bride advancing through a silver storm of flashes and applause. Life isn’t like that, and—you can take my word for it—death isn’t either.

![]()

Daniel at parties is something worth addressing. And why everyone chooses to look the other way when Daniel enters one of his dark phases. And why everyone goes with a “pobrecito” instead of a “pobre tipo.”

Daniel doesn’t wait to deposit Hilda in the coatroom. Daniel doesn’t think twice about leaving Hilda alone in the dark. I lose sight of Daniel because, when they separate, my unknown camera director always focuses on Hilda. Tonight Hilda is not alone, from a dark corner in the room emerges another little girl. A strange little girl, deformed, uglier than Hilda. It takes a few seconds for me to adjust the controls and to determine that the girl is wearing a mask. Turtlehead.

“What’s your name?” Turtlehead asks in a deep voice, attenuated by the rubber mask.

“Hilda,” Hilda says.

“My name is Selene,” Turtlehead says, and I realize that Hilda is jealous of that name, because Selene is Latin for Moon, and that she would like to have the name of a celestial and solitary body. Hilda longs to live in orbit.

“Earth is the third planet of nine that make up our solar system,” Hilda recites, spinning the pillow in front of the little holes in Selene’s mask, as if wanting to hypnotize her, “and it has a moon whose distance from Earth, from center to center, is 238,855 miles. The Earth and the Moon travel an average of 66,620 miles per hour in an elliptical orbit of 584,017,800 miles around the Sun and . . .”

“What are miles?” Selene interrupts.

Hilda gets nervous and shuts her eyes and squeezes her pillow very tightly.

“Did you know that Selene means Moon?” she asks, changing the subject.

“No.”

“What do you want to be when you grow up?”

“Donatello, the Ninja Turtle . . . And you?”

“WhenIgrowupIwanttobethepersonwhodiscoversirrefutableproofofintelligentlifeonotherplanets,” Hilda says, and smiles, satisfied at not having made a mistake.

The two of them look at each other in silence for a second.

“Are you also like me? An extraterrestrial?” Hilda asks in a whisper.

Then someone comes into the room, a man lurching, and the two of them scream as if possessed and run out of there, and I can’t stop laughing like a madman or a dead man, here above, here below, here wherever.

![]()

It’s like this: at parties Daniel functions something like a roller coaster. The slow and apparently calm ascent, a slight curve, letting go and plummeting down with arms in the air, eyes wide, mouth open in a full-throated scream.

Daniel screams. Daniel shatters plates and glasses against the wall. Daniel explains that it’s a Greek custom. Several people grab him and throw him to the ground. They tell him to calm down, that he’s acting crazy. Someone goes to find Hilda and asks her to please take him home. As if Hilda were an adult. Hilda has that effect. People speak to her in clipped phrases and short sentences. People don’t look at her face when they speak to her. People prefer to stare at that planet Earth–shaped pillow and to speak directly to the spot where Russia appears. People speak to Hilda as if they were talking on the phone to someone very far away.

![]()

In the taxi home, Daniel spends the ride asking Hilda to forgive him with the voice of someone who, actually, is demanding an apology without really knowing why. Hilda doesn’t pay him much attention. Hilda says, “Yes . . . Yes papi . . . don’t worry,” and she squeezes her pillow tightly and thinks about getting home fast so she can go lie down beside the washing machine. Even though there’s no sound in space, and Hilda knows this, it always seemed to her that the secret voice of the cosmos must resemble the sound that a washing machine makes when it’s running. A sound like a circular tide spinning around on itself, biting the tail of its own foam of stars.

Hilda thinks about the dark and heavy waters and about how the distance between the Sun and the Earth at the closest point in Earth’s orbit is 91,402,000 miles, and at the most distant point, is 94,510,000 miles.

Hilda thinks about how our solar system travels around the center of the Milky Way once every 225,000,000 years at a speed of 481,000 miles per hour. Hilda smiles soundlessly and remembers that the Milky Way encompasses a distance of 100,000 light years and that each light year equals 5,878,499,814,000 miles.

Hilda thinks about how right now there are more than 300,000 terrestrial objects orbiting the planet—orbital trash, scrap metal, bones of rockets and satellites. Mortal remains that, probably, are like the dead spinning around the living, who have abandoned them there forever.

Hilda thinks about something she read in the newspaper the other day: about how now you can shoot the dead into orbit, capsules with ashes, the price is exorbitant, but in the end, the thing about the dead going into the heavens is true.

It’s that terrible hour when those dogs take those owners out for a walk.

The taxi turns slowly down an avenue. Hilda loves the sound the snow chains make on the brakes and then she decides to think about Earth. About the 1,700,000 kinds of known species on the surface of the planet and the ghosts of the 5,000,000 to 35,000,000 organisms that are here, with us, and that mankind hasn’t yet been able to classify. I ask myself if I might be one of those specimens. Ectoplasm watching television.

Hilda, on the other hand, wonders if the taxi driver might not be the prototype of an unknown race. Someone who shouts and shouts and bangs on the steering wheel and turns around in the seat and grabs Daniel by the lapels and shakes him and tells him to give it a rest, that that’s enough, to stop saying Diana-Diana-Diana-Diana-Diana over and over.

Hilda sees that the taxi driver is missing a few fingers on one hand and wonders if that might mean something. The taxi driver opens the door and orders them to get out and Daniel begins to quiver again. Daniel is almost certain that the snowflakes are going to burn his face and his hands and his clothes; Daniel shakes himself to scare away a swarm of wasps of cold and pushes Hilda out of the taxi. Hilda slips and falls in the snow. Like in cartoons, as if someone has pulled the rug out from under her, she pirouettes back in the air and lands facedown.

Hilda thinks she could just stay like that forever, with her face cold and white and hidden. Maybe people would walk by and see her lying there and, unable to glimpse her face, would think to themselves, what’s that pretty little girl doing, Hilda thinks.

“What’re you doing?” Daniel asks her, and tells her to get up and then asks her to forgive him again. He asks her to forgive him as if the word had a very long number in front of it. A quadrillion light years of forgiveness and we’re just getting started, this is just the beginning, we’ve got a long way to go before we get to forgiveness.

Hilda pushes herself up with her arms and slowly gets to her feet, feeling suddenly light and empty, and then she realizes. The pillow. Earth. Urkh 24. The taxi. Hilda looks at her empty hands and wonders—Hilda has heard that crying redistributes the bones in the body; that it rearranges ideas; that, sometimes, it can even change things—if this might not be the right moment to cry for the first time, to learn to cry, to let tears fall like the falling snow.

Hilda asks Daniel what snow is, where it comes from, how it’s made, and what it’s for. Of course Hilda knows all the answers, she knows all about sudden changes in atmospheric pressure and the secret sound that, if you listen very carefully, you can hear a second before the snow starts to fall, the sound of someone pressing a button. Of course Daniel doesn’t. An Argentine model has no need to know what snow is for, it’s enough for him to know that the snow will change the trends in the next Winter Collection and that all those clothes will be a little harder and hotter and more exhausting to model but might be more fun to pose in for the photographs.

Hilda asks him to keep from crying.

Hilda thinks that maybe words function like a dish towel, like a floor rag; that maybe words dry, that words make you a more eloquent person and, as such, more deceptive when it comes to sentiments and sensations.

Hilda and Daniel walk under the snow and at first Daniel tells Hilda that he hasn’t the faintest fucking idea, that snow is for making all the taxis disappear, and then he smiles. Then he thinks better of it and he tells Hilda that, really, the snow is God’s dandruff. That when God gets mad, He shakes His head and He has a lot of dandruff and the dandruff slips through little holes in the sky, through the stars there above.

Daniel points up at the night sky and for a moment he almost tells Hilda that one of those stars is her mother, but no; he thinks better of it and better not because it would be like telling her that her mother is a hole.

Hilda smiles and hangs onto Daniel’s arm and thinks that she loves him so much without really understanding why, and it frightens her a little to think that that’s what love is: something you don’t understand and that you enjoy while you have it without asking questions or demanding answers, something almost extraterrestrial.

![]()

Here, in front of the blue and deep and submarine light of my television, I learned something that Hilda always knew. Some bad TV shows—the ones starring models, the ones in which the protagonists always seem to be playing the part of a psychopathic serial killer perfectly when the script is asking them to be romantic and affectionate—are actually a lot like real life; only a small group of privileged individuals find just the right screenplay for their dramatic potential.

Reality as we understand and live it is nothing but a huge casting call, and so the information—random data, whimsical thoughts, famous quotes, true stories?, fake news?—comes to me as confusing lines of letters filing uninterruptedly across the bottom of the screen like the peaks and valleys of the financial markets of the world.

Reality resembles television more and more all the time. Reality resembles “TV” more and more all the time, and the reality of what was—your own life contemplated on a dead television—is like one of those multiple-choice tests, with the crucial difference being that, right away, the answers begin to be erased by oblivion and we find ourselves hesitating in the face of suddenly supernatural questions like what’s your date of birth. And it isn’t long before nothing matters to us less than our own past, and we mark the always convenient option (d)—which tends to be all of the above or none of the above—and we choose to tune in the far more interesting and fun present of those who are still alive.

On my television, Hilda and Daniel are always perfect in their roles, and there’s something of poetic justice in my television or—maybe—something of cruel irony in that I spend all my time following them in front of this machine that never turns off.

I remember that my career began with the role of a blind child on an afternoon soap opera thanks to the soft connections my mother had with lecherous TV bigwigs, and that ever since, the idea of sex has almost always struck me as cold and functional and as easy to manipulate as the buttons on the remote control when zapping horizontally from channel to channel.

I remember—I remember less all the time or, which is almost worse, my memories resemble a bad TV show more and more all the time—that my family was very poor when I was little, in a small Patagonia town named Sad Songs. I remember that, back then, all my birthday presents had to be not only cheap but also endowed with a furious and immediate utility. My birthday presents had to be for something.

I remember that when I turned five, I got a broom, and I remember also that, days before leaving Sad Songs forever, when I turned six, resigned to receiving a shovel, my father showed up with a small television under his arm. Black and white and nobody dared ask him where he’d gotten it for fear of what the answer would be. I remember that we spent several hours sitting in front of it, and I remember that my father let escape a sigh as long and sad as the night that was falling down on us before saying, “But how great would it be if we had electricity, right?”

Ever since then, television and televisions never ceased to produce a cautious intrigue in me. It always struck me as strange the way in which people refer to the television as “the TV.” Why this affectionate diminutive nickname of the kind typically reserved for living beings, and why not, for example, “the fridgey,” “the washy,” or “the phoney”? What did televisions have that other household appliances didn’t? What caused that surge of affection—for a machine—that most people couldn’t even tune in for another person?

I never learned how televisions function or why airplanes fly or how the voice travels across telephone wires. Hilda always knew—for example—that “planet Earth is now going through what’s considered its middle age and that it originated 4.5 billion years ago out of a turbulent cloud of dust, gases, and asteroids suspended in orbit around the Sun. Over a period of 700,000,000 years, this cloud proceeded to settle into place until it gave way to what we know as our solar system. The destruction of our planet will take place within four or five billion years when the Sun, having consumed all of its own hydrogen-based fuel, initiates a process of expansion that will end up incinerating all the planets in its orbit. That will be the end of our solar system.”

Hilda knew this and the elegant malevolence of the people who write those informative texts never ceases to amaze me. I can’t help but notice that it predicts the beginning of the fire and the fury but says nothing about anyone who might still inhabit planet Earth. Will there be anyone left? I wonder if Hilda knows anything about that. One thing is certain: there is one thing I know that Hilda doesn’t. And it is this:

![]()

Every so often, the programming of my television undergoes certain intriguing alterations. Antenna adjustments. Interference. Sudden accelerations. The speed of things. Every so often, my television tunes in Hilda’s future. A snowstorm of dirty and gray static and I stop seeing Hilda walking under the snow, pulling Daniel by the arm. Then comes the secret hour when the night seems to gain momentum in order to arrive at the right ending, the precise instant when all the newspapers are starting to be printed, and if you put your ear to the cold asphalt, you can hear, with no trouble at all, the subterranean passing of a black-and-white river of news.

Then, in the future, the show is something else and the landscape is different. A desert. Mojave, Nefud, Atacama, Nostalgic Rancheras. It doesn’t matter, it’s all the same. The sand—the sand new and freshly made, the sand as old as the world—always looks like itself, and I see Hilda twenty years later, standing on a hillside, wearing the clothes of an explorer, like in one of those old adventure shows.

At Hilda’s feet a formidable expedition unfurls, ants working at digging holes, heavy machinery, men who ask her questions and seek her begrudging approval.

Hilda’s face is the same face that, in a matter of days, will appear on the cover of Time magazine and on the front pages of newspapers the world over.

Nobody will dare to say that Hilda is ugly then, because Hilda will be unique, and—in the first years of the Third Millennium—people will have already renounced the uniform idea of beauty and gone off in search of more singular attractions.

An explosion shakes one face of the hillside—more than anything I’m pleased to discover that Hilda is the one who presses the button of the detonator—and the mouth of a cave is left exposed.

Hilda enters first and walks ahead.

Hilda always walks ahead and first and advances and descends into the depths of her dream made reality.

Hilda stops in front of the mouth of a dark pit. Scaffolding and flashlights and orders in multiple languages.

Hilda descends down a rope.

Hilda suspended on a system of pulleys.

Hilda with a small camera on her helmet and a microphone in front of her mouth, which never stops moving, her voice speaking words that will soon be as well known as “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Hilda reaches the bottom of the pit and takes a few steps. An invisible sound falls over everything like the voice of the ghost of an ocean that once was and no longer is.

It buzzes in Hilda’s ears and she remembers the words uttered a few days before, near the excavations, by a sand warrior, a very tall man with a very deep voice, who had arrived to their encampment offering stories in exchange for food and water.

Hilda walks behind the thin beam of white light emitted by her flashlight until the flashlight ceases to be necessary. Now there’s more sun than at midday and she almost can’t tell that she’s underground and she enters and walks and arrives at the center of an enormous chamber of curved walls. It’s like having been devoured by a whale without even noticing, she thinks.

Hilda comes to a stop in front of a small steel pyramid that is floating a meter off the ground. On one side it has the drawing of the contours of a hand and Hilda is not at all surprised to discover that the size of that hand coincides precisely with the size of her hand. Hilda presses her hand against the side of the pyramid and it quivers like a cat that has spent centuries waiting for just such a caress.

The pyramid opens with the delicacy of a piece of origami retracing the path of its construction, and there it is, smiling in the half-light and suspended dust. The happy mummy of an extraterrestrial sitting on a throne, illuminated by a beam of yellow light as old as the universe. The skin rosy and tattooed with concentric circles, the oblong head, the eyes that seem to want to escape the skull, the mouth like a precise rectangular fissure, the double line of teeth, the four arms open wide to form a cross or to initiate an embrace fossilized in time and space.

“Urkh 24,” Hilda thinks then, and she embraces herself as if she has reencountered a long-lost pillow, as if she feels the entire world pressing against her body, the universe inside her body, as if she has come home after so much time out walking under the snow.

And in some fleeting place and for a long minute—through tears, my tears and the euphoric shouts of the members of the expedition and the prayers of the natives who point up at the sky and to history that has been changed forever and for the better—Hilda thinks about Diana and Daniel.

Hilda laughs like she always laughed, like when she was little.

Hilda laughs soundlessly and then she wonders what that other new sound might be and she discovers that it is coming from her, that now she is bursting with new and warm laughter.

Hilda laughs and thinks that she can’t believe what she’s thinking (irrefutable proof of intelligent life on other planets after all), what she’s thinking is that, yes, she is more beautiful.

Hilda is much much much more beautiful than the extraterrestrial. ![]()

Rodrigo Fresán was born in Buenos Aires in 1963 and has lived in Barcelona since 1999. He is the author of the books Historia argentina, Vidas de santos, Trabajos manuales, Esperanto, La velocidad de las cosas, Mantra (winner of the Premio Nuevo Talento Fnac, 2002), Kensington Gardens (winner of the Premio Lateral de Narrativa, 2004), The Bottom of the Sky (Locus Magazine Favorite Speculative Fiction Novel in Translation, 2018), and the triptych comprising The Invented Part (Best Translated Book Award, 2018), The Dreamed Part, and The Remembered Part. His next novel, Melvill, will be published in Spain in 2022. In 2017, Fresán was awarded the Prix Roger Caillois in France for his entire body of work.

Will Vanderhyden is a freelance translator, with an MA in literary translation from the University of Rochester. He has translated the work of Carlos Labbé, Rodrigo Fresán, Fernanda García Lao, and Juan Villoro, among others. His translations have appeared in journals such as Granta, Two Lines, The Literary Review, The Scofield, Slate, The Arkansas International, Future Tense, and Southwest Review. He has received fellowships from the NEA and the Lannan Foundation. His translation of The Invented Part by Rodrigo Fresán won the 2018 Best Translated Book Award.

Illustration: George Wylesol.