CRACK OF DAWN

In these ashes beneath a fine blue sky, you’ll find bones and memories, burned by wasted love. Fine flesh has been transformed by hot licks of flame into ash and scraps of charred flesh. The ashes are buried in a heap near the river’s edge. The summer has been dry and the river has been small. There are blackened bones projecting from the pile, for the wind has picked at the grave and the rain has eroded it, but for the most part, the grave has remained. Inside the grave, the ash has become sticky with mud that has partially dried after being first hot with fire then damp with dew, then baked by the summer sun, dew-licked again each morning, dried again by a new day.

These bones and ashes and spots of flesh are almost the end of the matter, such as an end can be determined.

Here is the beginning.

Carry you down at the crack of dawn to where the Sabine River flows, out where the fish can be caught with a cane pole and cheap fishing line, a floater made of a cork from a bottle of vinegar. Add a golden-colored hook, a squiggling worm, a soft lead sinker or two—squeezed onto the fishing line by pliers—draw back that cane and cast the weighted line into the river and watch the water spread in little circles around the line and slowly grow still.

The heat lies on the back of your neck and arms, which you have coated in cheap sunscreen that is more like turkey basting than a preventative. You are both warm and invigorated from having walked from town carrying your gear. Sixty years old and in fine health, retired early with a good retirement plan, and now you can do what you have always wanted to do come early mornings besides go to work. Fish.

Cast and wait.

And then they came.

In your ears the roar of an engine as the car comes down from the long Sabine River bridge, down the concrete boat track that leads to the water.

A man and a woman getting out with the man carrying a folded blanket and the woman carrying a shoulder-slung purse the size of a picnic basket, wandering down a side trail, braving brambles and water moccasins and the occasional swarm of mosquitoes. Stopping at a clearing that has been made by the flames of lightning one summer past, but is a perfect spot to spread the blanket and sit down.

A large rise of bushes grows in a green cluster between you and them. If they looked, they could see you. But they don’t look. The man sets to work as if he has just punched a time clock and has a quota. He is fondling the woman’s breasts through her clothes in a manner to suggest the breasts might run away. She has a black eye. A beautiful, one-eyed raccoon fondled by an ape.

From concealment you sneak closer to the swathe of bushes, peering through gaps in the limbs and leaves.

The woman lifts the strap of the purse off her shoulder, placing it beside her on the blanket.

His hands continue to move without tenderness, but with clutching precision. And then the woman, pushing him back gently, smiling, teeth shiny as porcelain, says, “Tim, I know you’ve been with other women. I know their names. I know when they call you and when you call them. Their perfume on your shirts is like poison to me.”

“Don’t be silly.”

“I know you have and I don’t like it.”

The woman has somehow scooted back from him, and the smile is gone from her face.

The man’s face is a thundercloud. “There’s going to be things in life you don’t like, woman. You’re mine. But you don’t own me.”

“That hardly seems a fair proposition.”

“It’s how the world is made. It’s God’s law that the man can do as he will. By marriage, you are my property. You know what happens when you don’t mind? And don’t talk like that.”

“Like what?”

He studies her face, her defiance new to his eyes.

“Like you have education.”

“But I do. I have college. I have a degree. You have you, but you don’t have me. Not anymore.”

“I’ll tell you again, and no other time, quit sassing me. You know what happens when you do?”

“I’m wearing it on my face.”

“That’s right, and such a pretty face. Don’t make me do it again. Don’t make me not want to look at you. That black eye is hard enough to stare at.”

And in her mind the woman thinks of all the times she “made him do it,” him wanting sex when she didn’t, him wanting dinner NOW, and the times when he wanted things so vague, she could neither understand nor deliver. The times she trembled in her bed, her phone taken from her, not able to visit friends, her food portions monitored to keep her weight the way he likes it. Remembers so clearly being called stupid and ugly and worthless and insane.

Maybe she was in fact the last. Driven there by a truck of circumstance, fueled on insecurity and his inexplicable meanness. She could live with her own insanity, if there was such. It was him she could no longer live with, hoping for respect to take root, hoping for love and change. She realized now, those things would never come.

She pulls a hatchet from her large purse, the hatchet she has polished like a precision surgeon’s tool, the one with the carefully wrapped duct-tape handle. When she pulls it back to strike, the sunlight sparks off the blade and she has a delighted front-row view of his shocked, wide eyes, his lips drawn tight, his head leaning back, as if that would help.

And then she strikes his handsome face.

The axe cuts through bone and flesh, smooth as a hot knife through a mound of warm butter.

LATER

Deep morning. A Boy Scout troop will be out for a march. Their Scoutmaster is tall and lean, a cool-skinned fellow without pops of sweat, even though the temperature rests heavy and hot on the marching troop of twelve. The Scoutmaster has little moons of sweat beneath his armpits, but they are faint, and his knees are jerking out and back under the cut of his khaki shorts. Their movements have a machine-oiled precision about them, as if he had been built to order in a Boy Scout Factory, a mannikin motorized and bolted, screwed together with laser beams and socket wrenches.

The Scouts who follow him in a long trail like ducks in khaki and red scarves, are made of the lesser stuff of flesh and bone, greased by sweat, swooned by heat, pumped with blood, not machine oil.

They walk along the edge of the highway toward the lake. Time of arrival planned for noon, but a pause by the Scoutmaster, as they enter the depths of the trail into the woods, to point out Poison Ivy and Poison Oak and a bluebird on a limb with a worm in its mouth, will put them behind.

The Scoutmaster likes to lecture. He knows a lot of stuff. He knows what kinds of blisters the poisoned plants make, the mating habits of bluebirds, the life of wriggling worms that do best beneath the soil. He points out a worm wriggling in dark loam.

In that moment, the worm lifts its wiggling head only slightly, as if in acknowledgement. Lifts it right where a beam of sunlight shoots like an arrow between the trees.

The beautiful bluebird, in mid-sweet song, spies it, turns into a miniature, bright pterodactyl that chokes its song and swoops down from its limb to claim its wormy prize. Soft and gooey, an avian treat.

Whoa, the Scouts say, obviously thrilled by this dark example of nature at work. Later the bird will fly toward town and rest in an apple tree in a backyard, belly full of worms. And it will sing until a redheaded kid with a BB gun and an accurate eye shoots him out of the tree and the bluebird falls to the ground. It will lie there overnight to be found by a stray cat and taken away into a wooded grove to provide a nice supper.

Next morning, the stray cat will cross a road after a scampering mouse and be hit by a car.

But back to our Scouts.

For all the Scoutmaster’s observation, he fails to note a thin black wisp of smoke rising above the trees, some distance away but noticeable to all the boys, who see it through limbs and leaves but don’t really give a shit. They are happy to pause beneath the shade of the woods to pretend to listen. They have lost their military-style line and have become a wavering group around the Scoutmaster. A long rat snake on the hunt crawls between the legs of one of the Scouts so swiftly and quietly, it goes unnoticed. Later, a wild hog will notice it, but that is another story, sad for the snake, happy for the hog.

MEANWHILE BACK AT THE RIVERBANK

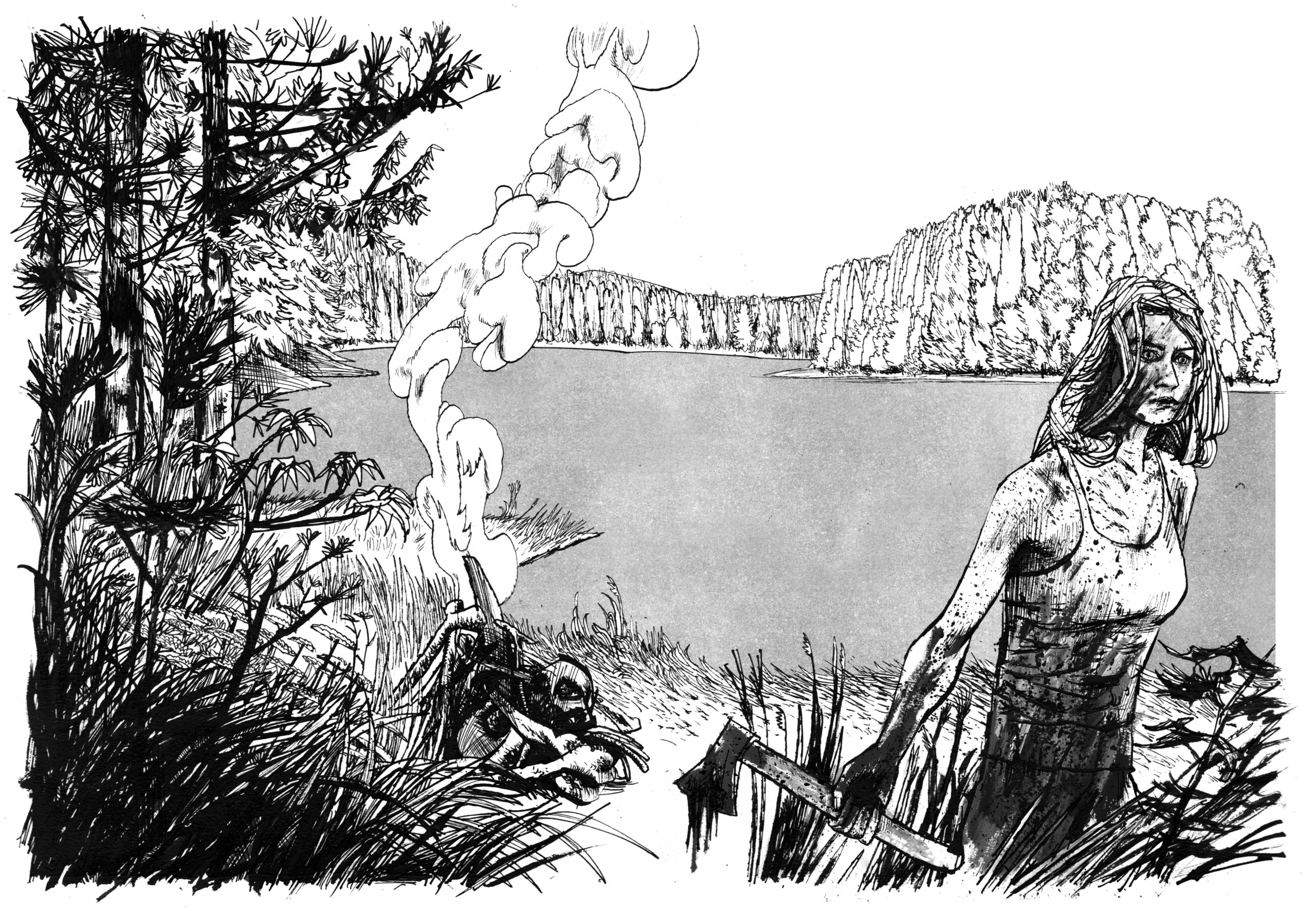

Axe murder in progress.

The fisherman hears and sees it all through the gap in the bushes, the woman swinging the axe in savage arcs, the blade cutting with loud but smooth precision through flesh and bones, the blood spray seeming to burst out in slow motion, hot, copper-colored streams and drops that glisten in the sunlight, fall and spatter to the blanket, turning it wet and dark. Her face, blood blemished, as if she is wearing a camouflage mask of blood and skin, her teeth drawn back and flecked with splashing gore.

“Oh shit!” says the fisherman.

As the words come out of his mouth, he knows he should have kept them tight inside. He drops the fishing pole as the blood-spotted woman’s teeth clench and her lips crawl and wriggle. She comes to her feet in one smooth move, like an acrobat.

The fisherman runs back to the river, darts down the trail along its bank. His boots smattering mud as he runs. Sixty years old but in prime health, he tells himself. I got this.

But swift behind him comes the Blood-Spotted Lady of Death. He hears the thundering of her feet in motion, and those thundering feet are gaining, and then he sees her shadow as it falls over him and his own shadow, its dark elbows and knees bending, flowing swiftly as if pushed by the wind. Her shadow raises its arm high and swings the shadowy axe in a swift dark curve.

There is a sudden burst of crows lifting in a dark, startled flock, up and away from the trees, their little shadows clutched together, dragging the ground.

CHOPAPALOOZA

She discovered that it was easier than she thought to drag the men to the riverbank and into a muddy pit carved by water, pull off their clothes, and take her axe to their flesh and bone, chopping and chopping, so happy that once or twice, she burst into song.

Retrieving the full gas can and shovel she had placed in the trunk before luring her prey with a promise of romance renewed, obedience accepted, hand jobs and blow jobs, oral and anal, and traditional too, she brings them to where the butchered bodies lie.

She pours the gas onto the chopped flesh and bones of the men, on their clothes, then gathers dry wood, scoops the gassy, bloody remains onto the pile with the shovel, and with her husband’s lighter, sets it all afire.

Flames jump so high and hot they crinkle the tips of her hair. An eyelash is toasted. The skin on the hand that holds the lighter is lightly kissed by fire.

Tossing the shovel and the gas can, even the lighter, out into the river where the current moves, she enjoys the splash, as if it is the burst of energy that created the universe. The cotton blanket she folds carefully and places on the blaze.

Flame wraps around the cotton, blood-soaked blanket, and caresses it rapidly to ash. Wood in the fire crackles. Bones in the fire burst. Flesh sizzles. Blood boils. She does a dance with her hatchet in her hand. Dances three circles around the fire. She sings again. Her voice is deep. When she stops to breathe, from where she stands, she can see the Sabine River bridge.

All the while that she has chopped the men, built the fire, danced and sang, cars have been whizzing by. No one has noticed. Or perhaps she has been seen, but no one understands what they see. Most likely, eyes were on concrete or the horizon.

My lady, she says to herself, your escape route and conveyance await. Away, my lady.

Finally, reluctantly deciding to let it go, she tosses the hatchet into the slow-rolling, brown water.

She leaves with a spring in her step and the odd feeling of having had an orgasm, made by chops instead of thrusts.

Moments later, the Scoutmaster and his troop arrive like a khaki cyclone, crashing through brush and dodging between trees, on out to the edge of the river.

The Scouts run along the riverbank and point at the smoke and yell, and one, with a droopy face, his sweat-damp hair cut close under his field cap, looks at the remains of the fire, says, “Look, bones! People bones!”

The Scoutmaster strolls to the smoking pit full of burnt wood and bones and curling black smoke, and looks. Pursing his lips, hands on hips, face puffed with satisfaction, he says, “Son. Don’t make foolish pronouncements. Don’t you know a cook fire when you see it? Meat has been cooked here. Animal meat. Not human meat. Hog, I believe, from the state and size of those bones. But human bones? Not at all. As a Scout, you need to know what to look for.”

The boys begin to pogo around the fire like hungry cannibals.

“Eat them bones,” one says, and then another. It’s a ring-around-the-rosy of voices and leaping.

“Stop!” the Scoutmaster says. Then: “What is our Scout rule that has been broken here?”

The Scouts freeze, study the face of their oracle.

Droopy Face steps forward, says, “Never leave a fire burning. Smokey Bear says the same.”

“He does. And what is the rest of that rule?”

“Leave the place like it was before you used it.”

“Correct. It shouldn’t look as if a fire were ever here. Scouts! Camp shovels.”

Camp shovels are removed from backpacks and unfolded. The boys set to work digging a pit next to the existing one. They rake the remains of the wood and the bones into the pit and cover it. One of the boys leans into Droopy. “Looks like a piece of human skull to me.”

But Droopy is defeated. “Scoutmaster knows what’s up, not you or me.”

The boy who still thinks Droopy was right, and that there is in fact a piece of human skull in the smoking pile, tucks in his thoughts, digs with the others, and covers the remains. By nightfall, he will have forgotten all about it.

Eventually, they smooth the burnt spot into a mud slab on the banks of the old Sabine.

THE HATCHET LADY

She reports her missing husband and the cops ask questions. She looks teary, and the tears are tears of freedom, but the cops falsely believe the loss of true romance glistens on her cheeks. A search is made all over, but turns up nothing.

One of the cops is quite handsome. He wishes he could meet a woman like her. One that would cherish and hold love delicately. He is secretly smitten.

In the meantime, a fisherman’s car is located near the river, well back from the big bridge. Parked on one of the red dirt trails, not too far from where the river flows. The fisherman is missing too. He has no wife. He has no friends. He’s retired. All that is known about him is he likes to fish.

His rod and tackle box and some sun-toasted worms in a bucket are found. Thoughts are that he slipped and drowned and has been borne away. The river is assumed guilty of murder.

As for the Hatchet Lady.

At the Methodist church the Hatchet Lady attends, rumor is her husband has abandoned his job as well as his wife. Ran off with another woman. Someone quick to drop their knickers and take up with wedded men. Has her own car, most likely, and they have rode away in it. It’s been said by some to some others who know some others, that he and a hot blond with a dress so short she has to powder two sets of cheeks, have been seen somewhere up in Waxahachie.

The Hatchet Lady gradually acquires the personality of a bird freed from a cage. She sings in the choir. In time she will marry the handsome cop that came to ask questions. The search for her husband gets lost in the shuffle of time.

THE RIVER

Rain storms come and go. They wash the river and make it flow. The river expands and covers the bank where the bones lie buried. Over time, the water erodes the shore. The burnt wood, bones, and memories of murder that the shoreline knows, are washed away in a torrential downpour, dissolving wood, tumbling those hatchet-snapped bones on out into a fast-flowing current.

In the night, the full moon lies on the water like a flat polished stone. In the day the moon goes away and the sun comes up, makes the water yellow and shiny. Moonlight and sunlight rise and sink.

And the river churns along, sometimes fast, sometimes slow, carrying the remains of the men out to the Gulf of Mexico. ![]()

Joe R. Lansdale is the author of fifty novels and four hundred shorter works, including stories, essays, reviews, and film and TV scripts. He has received numerous recognitions for his work, among them the British Fantasy Award, the Edgar, the Spur, and ten Bram Stokers for his horror works. He is a member of the Texas Institute of Literature, has been inducted into the Texas Literary Hall of Fame, and is the writer in residence at Stephen F. Austin State University. He lives in Nacogdoches, Texas, with his wife, Karen, their pit bull, and a cranky cat.

Illustration: Matt Rota