We got the gig from our singer Gary’s cousin, who was in the music business. Or actually he was still in junior college now, but he was moving to Nashville in the fall to go to Belmont, where they had a music business school. I was very impressed. I didn’t even know there was such a thing as music business school.

I was seventeen and it was summer break, July, and nobody had anything to do. I’d been fired from my job at a drive-through frozen custard stand, which was really just mediocre ice cream, for having a bad attitude. That’s what my supervisor said, after my first week. I showed up for work and he sent me home, then he called my house and said, “Sorry, we have to let you go.”

“Why?” I said.

“It’s just not working out.”

“Why?”

“Because you have a bad attitude.” Then he hung up.

I was shocked. I wasn’t rude. I didn’t talk back. I didn’t even really hate the job that much. All I had to do was wear a headset and take the order and then take the money and then hand the change back and then hand the food over. Sometimes I wished customers in the drive-through would have a fender bender and fight over it. Maybe that was it. I spent the whole night afterward riding through the neighborhood, flashing my brights at deer on the roadsides, wondering what in the hell was wrong with me.

Anyway, I got fired and I had nothing to do. Aaron was mowing yards, so he was free at night, and Lord only knew what Gary did for money, but somehow he always had some. So Gary’s cousin shows up and tells us he can get Stockholm (that’s our band) a gig “out of town,” and of course we said yes. So what if it was only in Greenville, Mississippi? That was two whole hours away. Might as well have been New Hampshire. It was more than half the way to Memphis, for Christ’s sake. And like Gary’s cousin (his name was Steve, I should have just called him Steve) kept saying, it was in a club. Like, with a real PA. The only place outside of Gary’s bedroom that we had ever played was this one youth group coffeehouse event at church, and it was awful.

We didn’t have a van or anything, so we just had to take Aaron’s dad’s pickup truck, load the gear in the back, and hope it didn’t rain. The radio worked, but only the passenger window rolled down and there was no AC. Like I said, it was summer in Mississippi, so we’re talking temperatures in the upper nineties, even at night. I didn’t care though. We were headed north to play a show in an actual club, where people would come to see us. Our very first out-of-town gig.

“This is how it starts,” said our singer, Gary. He was the one with the talent.

“How what starts?” I said.

“Our career,” he said. “Our whole fucking lives.”

Sweating in a pickup truck with three other dudes didn’t seem like much of a life, but whatever. After a few shows we would get a van, then when we were really big, a bus. Hadn’t 3 Doors Down been from the coast? Sure, they sucked, but that just proved the point even more. If it was possible for them, it was possible for anyone.

We stopped at a gas station and I bought a Coke Icee and a corn dog and a pack of Twizzlers. I was starting to get excited.

We pulled into town around sunset. Greenville was all gray and busted and falling down, a wreck of ugly and broke, right up until a series of ancient mansions rose up like ghost cavalry out of the soybeans. One minute there’s an old guy asleep on a porch with flies on his beer, and the next you’re in a sea of gazebos.

All the streets were named after Confederate generals. The sidewalks were cracked, with little tufts of yellow weeds squeezing through, trying to be pretty. Most of the stores were shut and bolted. An old white man rode by on a bike, his bony ass hanging out of his blue jeans. Aaron honked at him, and he gave us the finger.

The club was called the Hangar and we passed it twice before we found it. The parking lot was full of busted beer bottles and old Wendy’s bags. A stray cat huddled under a truck, waiting out the sun. The back door to the bar was open, and I followed Gary inside.

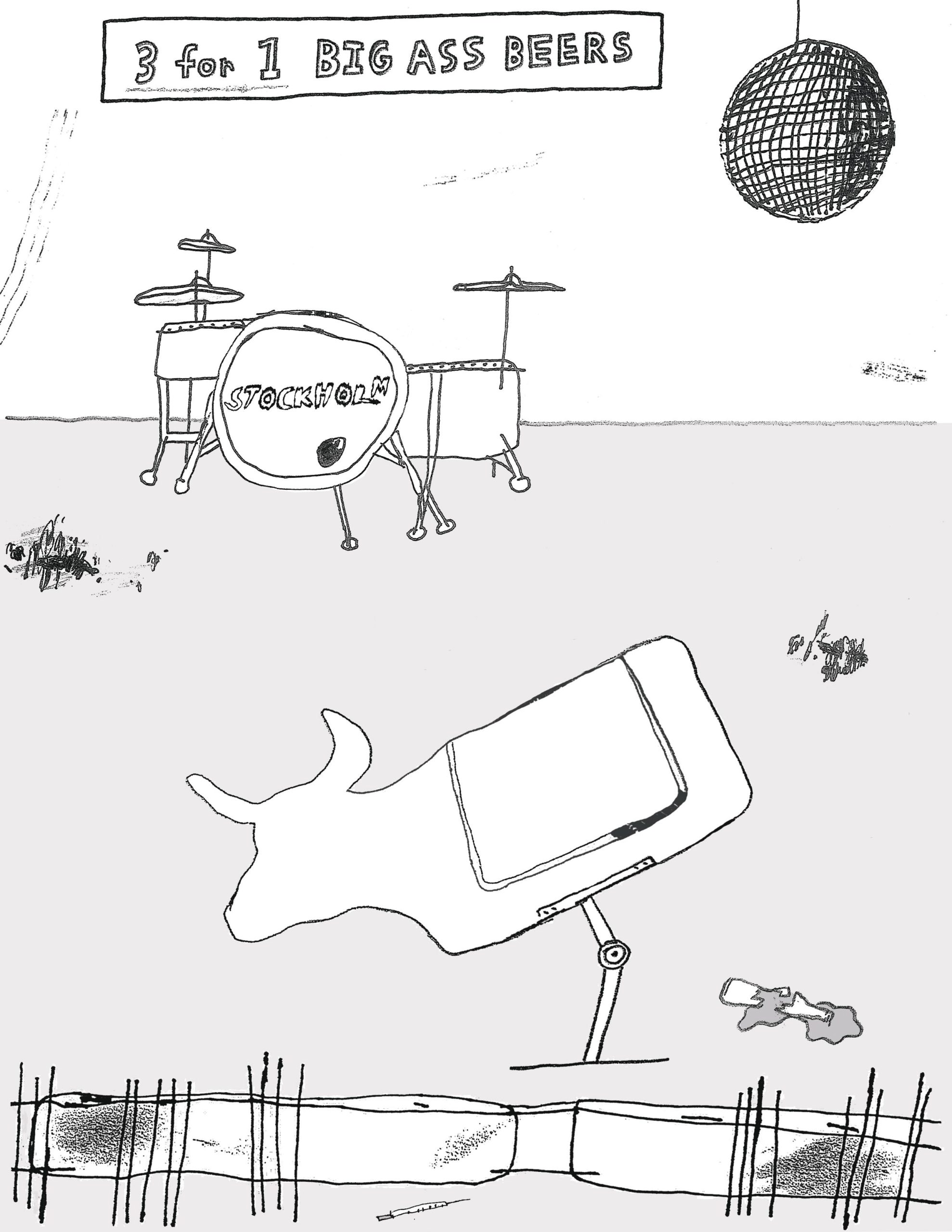

The Hangar was shocking. I’d never been in a place like it before. The barstools were crooked and the bathroom had a chicken leg on the toilet seat with a hypodermic needle floating in the bowl. My shoes stuck to the ground with every step, and the whole place smelled like BO and spilled beer. The bartender had a bulldog with one eye who lay there, belly to the floor. A broken-looking mechanical bull sat crooked in the back, surrounded by a sea of soiled mattresses. Pink lacy panties hung rotting from the ceiling fans. There was an old jet turbine in the corner, for atmosphere. I wondered where they’d gotten it. I wondered who would have gone through the trouble.

The club owner was a guy named Poe. He had a goat beard sprouting off his chin.

“You boys are on for two sets,” he said, “one from nine to ten thirty, the other from eleven thirty to one. In between there’s a wet T-shirt contest. You play your cards right, some of them girls might come home with you.”

“Sounds great,” said Gary. “We’re your boys.”

“Better be,” said Poe. “Look like a bunch of queers to me.”

He walked off.

“How are we supposed to play for three hours?” I said. “We only know eight songs.”

“We’ll just play every song twice,” said Gary. “Or three times if we have to. That’s what the Beatles did in Germany. That’s how they got so good.”

“But we’re not the Beatles,” I said.

“The Beatles suck,” said Aaron.

“You guys are idiots,” said Gary.

We unloaded our gear and lugged it in through the back door and up to the stage, which was only about a foot off the ground, tucked in the back of the room. Everything seemed to have survived the drive. I gave my bass a good thump, and the low end thudded all the way down to my toes.

Gary asked Poe if we could soundcheck.

“If you want,” he said. “PA’s over there.”

There was only one mic, for vocals, and nothing for the kick drum or snare. That was fine. Aaron was the loudest drummer I’d ever heard in my life. At practice we begged him to play softer, just so the neighbors wouldn’t complain. Gary did a mic check, and we blasted through a song. We actually sounded pretty good. It was amazing to hear our own songs belted out into a bar, a real actual bar. I started to feel a little bit okay.

“What do we do now?” asked Aaron.

That was a good question. It was still an hour and a half before we were supposed to go on. Poe vanished, and the bar was completely empty. I went over to pet the bartender’s dog and he lifted his head and growled at me.

“Might want to stay back from him,” said the bartender. “He’s a sweet boy, but he’ll rip your nuts off.”

I let the dog be. Gary figured it was lame to stand around onstage like a bunch of assholes, and since there wasn’t any greenroom that we knew about, we went back outside and sat on the tailgate of the truck, watching the night come on. Slowly the moon poked out and gave some mystery to the parking lot. Potholes became faces, greasy puddles became mirrors, mangy dogs turned demon in the dark. The moon can do stuff like that. It’s like the moon is a beautiful woman who walks into a room and makes you feel like a king just by noticing you. In the right kind of moonlight, anybody can be the Beatles, or at least a third-rate Deftones.

Back in the Hangar things had gotten interesting. The place was split into two rooms, a bar space with booths and a stage area, connected by a big open archway. The bar was hopping, sort of. A few old guys sat drinking at the bar. A lone woman in a cowboy hat smoked a menthol. At least there would be a crowd for us.

I started to get nervous, and suddenly I had to pee. Too late. It was time to go on.

We kicked into the first song a little fast. Aaron broke a stick, and Gary’s guitar was kind of out of tune. My bass was fine. I played the parts just right. I pulled my hoodie on, even though it was hot as fuck in there, just for effect. I hoped it looked cool.

When we finished, nobody clapped. It was almost like we hadn’t been playing at all.

Still, some people were starting to show up. Old guys, sure, but also young dudes in cowboy boots who were around our age, or maybe a few years older, with their hot redneck girlfriends in tow. One of the young guys got on the mechanical bull and the thing jolted into action, half-assedly slinging him around while he laughed and made fake cowboy noises. It didn’t seem much of a bull to be honest. Not much fight left. Any moment they could unplug that mechanical bull and walk it out to the junkyard forever. I got distracted and flubbed a chord change and Gary shot me a scowl, so I put my head down and stared at my shoes, trying to look cool again.

We finished, and still nobody clapped. Song after song, nobody clapped. They barely even looked at us. It was like we were too negligible even to boo. I started to get that peripheral feeling again, like the universe was some other world where things happened, and I was a kind of human breathing ghost. At least when we’d played at the church coffeehouse an old man had covered his ears and frowned. A little hate is better than nothing.

By our sixth song, I was so depressed I couldn’t even look at the crowd. At least this one was fun to play. It was called “Drone Gods of Middle Earth,” and it was probably about war or something. It was loud and fast, our heaviest song, and it was so easy I could play my bass part with one finger. You could really headbang to it, is what I’m saying. If anything was going to get the crowd’s attention, it would be that one.

Across the room two women crawled onto the mechanical bull. One had black hair and the other’s was a fake-looking orange. They were both gorgeous, in that specific way only small-town redneck girls with fake dyed hair can be. You either know or you don’t.

The bull got to bouncing.

I don’t know. That’s when something strange happened.

Maybe it was a change in the air, an electric fuse popping in the bar somewhere letting out some magical spark, or maybe it was just the frustration of not being heard. Maybe it was the magic of those two women on the mechanical bull, I don’t know.

But all of a sudden we sounded great.

Gary was screaming his balls off, and Aaron hit the drums harder than anything I’d ever thought possible. Even my little Ampeg bass rig was shuddering the earth beneath me like a whole squadron of thousand-pound war elephants. I felt historic. Fuck the Beatles. Fuck even the Deftones. We sounded like goddamn Hannibal storming the Alps. I climbed up on my bass amp and took a leap off, landing perfectly on the beat, like a fucking badass.

Everyone in the room could feel it too, even if they weren’t watching us, I just knew it. We were all locked in, all moving together, even the cowboy guys with their backs to us tapped their feet to the beat. The two women on the mechanical bull kept gyrating, moving in time to our music too, like even the bull had caught the beat, puny as its bucking was.

The black-haired woman pulled the orange-haired one’s top off. She had big titties. In the bar lights they looked glowing, radioactive. The whole crowd roared, and people started throwing beer in the air. I’d never seen an actual titty in real life before, not since I was old enough to know what a titty was. It was incredible, the whole thing. I watched the bull putter out, defeated, and the two women raised their arms up in the air, breasts free and beautiful. Then they leaned into each other and kissed, long and slow. Not in a show-offy way either, but in a way that seemed like they meant it, like it was the best kiss of their whole lives, the weird barroom lights on them, everyone cheering, surrounded by bar trash and stained mattresses.

All soundtracked by us, by my shitty band that had just figured out how to be the greatest band on the planet.

That’s when some drunk guy, probably the orange-haired woman’s boyfriend, walked up and grabbed her by the shoulder, yanking her right off the bull and onto the mattress. He stood over her, screaming at her, waving his hands all frantic. I couldn’t hear a word he was saying, not over our band and its holy, righteous noise. He must have pissed the black-haired woman off, because she leapt from the bull and landed on his back. I think I saw her take a bite out of his neck. Another guy jumped in, trying to pull her off his back, and the orange-haired woman kicked him in the balls.

“Drone Gods of Middle Earth” had this one great part, a big pause right at the end of the bridge, before we kicked back into the chorus one last time. It was my favorite part of the whole song, the kind of thing you can imagine millions of people loving if you shut your eyes and pretend hard enough. I tell you, that pause was my absolute favorite thing we had ever written.

Anyways, right before we came to the pause, the guy who got himself dick-kicked turned around and backhanded the orange-haired woman in the face. I saw blood sling itself from her mouth in a red splatter across the dirty mattresses.

This was the exact moment of the pause.

In the sudden silence it was like the whole room took a breath and held it right quick. The whole bar had gone silent, still, like nobody could believe it, like a permanent line in the night had been crossed, and there was no coming back.

We bashed into the chorus one last time, perfectly on beat, the three of us playing better than we had in our entire lives. As if on cue, the orange-haired woman screamed. She screamed so loud I could hear it over our music. It was the loudest scream in the world.

It wasn’t a hurt scream, or a pained scream. This wasn’t a cry for help.

It was pure, furious anger.

The orange-haired woman wanted blood.

She leapt at the man who’d punched her, face bloody, fingers out like claws.

That’s when everyone in the bar rushed in. I mean it. The teenagers, the old guys, the woman in the cowboy hat, even the bulldog, roused like an angry god from his slumber, ripped the pants of a man wielding a busted wine bottle. It was like somebody had tripped an alarm, like this was the moment they’d been waiting the whole night for.

We finished our song. Again, nobody clapped. They were too busy beating the hell out of each other.

“What do we do?” I said.

“We pack up our shit,” said Aaron.

“Fuck that,” said Gary. “We’re not going anywhere. We haven’t even played ‘Penumbra of Sorrow’ yet.”

That was Gary’s favorite song. It was a ballad about his shitty ex-girlfriend Clara who everybody hated. It was like seven minutes long.

A tall middle-aged man in khakis came running up to the stage, chased by this fat guy in a Hawaiian shirt. I thought he was going to hit me in the face. The tall guy grabbed Gary’s mic stand and swung it like a baseball bat. It hit the fat guy in the head so hard I saw a tooth leave his mouth and arc through the air, a gory star falling.

“We’re leaving,” said Aaron. “Fucking right now.”

He grabbed half his drum kit and ran it outside. I lugged my Ampeg and hurled it in the back of the truck, Gary tossing armfuls of cords and pedals like they were junk. In minutes we had it all packed up in a heap of gear. I only had my bass left to grab.

I ran back into the Hangar.

The bar people bashed each other. The cowboy woman smoked her menthols. The bartender punched a man in a red polo shirt. It was hard to take your eyes off of it, all this chaos, like how it must have been in the universe right after the Big Bang happened and sent all those molecules flying, so they could tangle and burn and make up the cosmos. It was so beautiful I wanted to watch it forever, the way you do the first time you see a waterfall, or a burning building. Destruction and rebirth, the pure roaring energy of it all.

I heard a growl from the floor. The one-eyed bulldog. He had blood on his snout, and it sure as hell wasn’t his blood.

“Easy, buddy,” I said, backing away.

The dog ran toward me. I ducked a bleeding regular and pushed him down in the dog’s way. Didn’t help. He leapt over the man like so much debris and kept coming. I ran, cutting a path through the crowd, seeking high ground. And then I saw it. The mechanical bull.

I scrambled up the mattresses, crawling over the brawlers, until I stood atop the bull. The dog leapt up at me but I dodged him okay, trying not to fall off. He couldn’t get up top the thing. Maybe his legs were too pudgy, I don’t know. He barked at me, snapping at the air.

I was safe, kind of.

But then I realized everyone was staring.

The beat-up, the bloody, the mangled. Rednecks and lawyers and off-work nurses and whoever the hell else. Looking up at me, like I was some kind of rock star.

“Show us your tits!” yelled the orange-haired lady.

The bulldog took a running start, bounding up the mattresses, preparing a mighty leap. He was going to make it this time, I knew that, he was going to tear my nuts off.

So I did the only thing I could do. Just as the bulldog went airborne, sailing straight toward me, I jumped as far as I could, hurling myself out over the gathered crowd.

I don’t know. I thought maybe they would catch me, carry me out like a hero to safety.

They did not.

I crashed hard on the tail end of a busted mattress. I whirled around, expecting a face full of teeth lunging at my throat.

The bartender had his dog by the collar. It was snapping at me, slobber flying, trying to yank itself free.

The bartender had a cut on his cheek and his nose was crooked, bleeding.

“Get out,” he said. “Now.”

I got up and ran myself toward the exit. But when I stopped to grab my bass, I saw something there, lying on the ground. The fat man’s bloody tooth. It lay at my feet like an offering.

I don’t know why, but I bent down and scooped up the bloody tooth and stuck it in my pocket. When I got to the truck, Aaron peeled off before I even had the door shut.

“This is bullshit,” said Gary. “We didn’t even get to finish our set.”

“I think my kick drum’s busted,” said Aaron.

“What a terrible night.”

“The fucking worst.”

I crouched in the back seat, feeling like I was about to puke. Outside, horrible Greenville became the clear, cool Mississippi countryside. I looked out the window and watched the moonlight make a cosmos out of a cotton field. I couldn’t stop thinking about those two women glorious on their bull, making out to our own band’s music, to the huge crushing sound of it. How quick it had all plummeted, limbs flying, orange hair yanked out in troll-doll handfuls, while our music raged behind it, fueling the melee.

I remembered it over and over again, fingering the bloody tooth in my pocket.

This is the world, I thought. I’d heard about it, seen glimpses of it around town, maybe when my parents had too much to drink, or else when Rod’s stepdad Jonathan crashed his car into a lamppost outside my house. But never had I been so close to it, never had I been a part of it like this. I shut my eyes, and in that horrible truck bouncing down the shit Mississippi highway with a whole sky full of angels watching down, I smiled.

This was the whole world, and I was finally in it. ![]()

Jimmy Cajoleas was born in Jackson, Mississippi. He lives in New York.

Illustration: Josh Burwell