“Print the Legend” | A Conversation with Elizabeth Nelson and Patterson Hood

Interviews

From Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up in Blue,” which begins as a forensic examination of a doomed love affair and ends as a sad valedictory for a lost generation, to the beautifully elliptical, slow-moving tragedy of Sly Stone’s “Family Affair,” to the deep workingman’s blues of Merle Haggard’s “If We Make It Through December,” story songs are a subset of the songwriting process all their own. Notoriously difficult to pull off—you’ve really got to be on your game to hold people’s attention through a three-act narrative—they are also about as affecting as music gets when carried off with aplomb. “Print the Legend,” the newest single from my band The Paranoid Style, is not the first story song I’ve written, but it’s probably the most personal and emotionally complex. Two go-nowhere misfits meet at random strip mall, one terrible idea is mutually arrived at, and a lifetime of quiet ramifications occur.

I am tremendously proud of “Print the Legend,” and wanted to try to better understand what makes a great story song tick. So I dragooned my buddy Patterson Hood from the Drive-By Truckers—maybe the best American story-songwriter since Warren Zevon—into a lengthy discussion of some of our favorites. Playlist at the end, for the truly bold and uncompromising.

Elizabeth Nelson: So, we’re here to talk about story songs! I wanted to discuss this topic with you because you are not only a master at narrative songwriting, but such a great music fan and listener. I’m just going to throw one out there that has obsessed me for a long time: Robert Earl Keen’s “The Road Goes on Forever.” An immense song, as far as I’m concerned. It’s got everything: love, billiards, Miami, rafts of coke, and a trip to the electric chair. Basically the full human experience. You know this tune?

Patterson Hood: I love that one. When we were first starting the Truckers and playing the Star Bar in Atlanta, this guy used to make me these amazing mixtapes and one had that song. If I remember correctly, that was the first song on it. It also had “Kerosene” by The Bottle Rockets, which I think is one of the most underrated story songs ever. I always think of that song from that point in my life, because I was relatively new to the idea of writing story songs at that time.

I’d been writing songs since I was eight, and at some point I got really bored with my own life, or at least writing about it. My personal life was in a fairly stable place for a minute there, and I just kind of felt like I’d written too many songs about myself. Also, I think it was a reaction to the ’90s, all of the self-pity songs. It’s like, well, I’m going to write about something that’s more interesting to me than me.

EN: Same here. At a certain point in my writing, I just felt like, Does anyone care that much about my relationships? Do I care? Is that interesting? And that’s when I started writing songs about Alan Greenspan or whatever. It’s probably been a dumb move professionally, since people apparently literally cannot get enough of unrequited love songs or breakup songs. But, I mean, sometimes the problems of two people don’t amount to a hill of beans, right? It’s a big world out there.

PH: Almost to a one, the real greats always build a universe that’s bigger than their personal concerns.

EN: Speaking of greats, let’s talk about Townes Van Zandt’s masterpiece “Pancho and Lefty.” It’s so beautiful, but man is it rough. It seems to say that even the closest of brotherhoods can be transgressed by money and avarice. You can read the song as dumb, arbitrary happenstance, or you can read the song as an overarching thesis on manifest destiny ethos. Either way, the emptiness is endless.

PH: You can read that song in a thousand different ways. That’s one of the most brilliant things about it because it says so much while leaving so much unsaid. The whole story is implied just by little details. He lets you make up your own story. I think everybody has a different interpretation of that song. Townes’s mastery of subtle detail is astonishing.

EN: When we were prepping for this you mentioned Tom T. Hall. I’m a fan but not an expert on his work. What brought him to mind?

PH: I can’t talk about story songs without alluding to the great Tom T. Hall. About the same time that friend in Atlanta started giving me those mixtapes, another friend found out that I was basically ignorant of Tom T. Hall.

So, I got a hold of this tape of Tom T. Hall, and we would listen to it in the van on tour, just over and over and over. Mike Cooley and I both got obsessed with it. I think Hall might be the greatest story-songwriter of all. He gives you the details and he leaves a lot out.

EN: Could you recommend a favorite?

PH: “Pay No Attention to Alice,” which I actually covered on one of my solo records, is a stunning portrait of a friend’s alcoholism. “Homecoming”—I mean, that’s like a novel right there, and in a three-and-a-half-minute song. Again, it leaves so much unsaid and yet it gives you so many details.

EN: Let’s talk about your own “Puttin’ People on the Moon” from DBT’s 2004 LP The Dirty South—an incredible story song. For me, my interpretation is you’ve got a small-town Huntsville drug dealer who’s trying to save his uninsured wife from cancer and who’s cast against this incredible federal boondoggle of NASA. It’s about hypocrisy.

PH: Sure. The narrator is actually from my hometown of Muscle Shoals, which is like an hour and a half from Huntsville. When I was growing up, Huntsville was a boomtown, which it is again now, but when I wrote that song, Huntsville was in a really bad slump. Muscle Shoals is doing better now too, but it struggled for a while. They closed the fourth plant the week I graduated from high school, and my hometown was in about a thirty-five-year depression. Very parallel to Flint. During a lot of that time, Huntsville was having this incredible population and economic growth, and there was NASA money, then other industries that came in on the periphery because of that. Not only does the narrator feel left behind, he feels like his town is left behind too, while this town down the road has all this stuff.

EN: Super-interesting background. What influences caused you to write this particularly idiosyncratic and angry story song at this time?

PH: One of the inspirations for that song was Gil Scott-Heron’s “Whitey on the Moon,” which I love and which I’d probably just recently fallen in love with. When we were writing The Dirty South, part of our idea was to basically approach songs with the same subject matter as hip-hop songs, but from a different point of view, which maybe on some levels the sentiment doesn’t age well or doesn’t sound good in 2023, but I think it was coming from a pretty sincere place of at least good intention.

To me, rappers were the only people who were really talking about the shit that I thought was really important. Nobody in the idiom of rock ’n’ roll that I considered us to be in—except for a handful of really angry punk rockers or folk rockers—was talking about the political aspects of so many being left behind. It all came out of that train of thought.

I wrote “Puttin’ People on the Moon” in the passenger seat of the van, when we were driving from Nashville to Atlanta. I don’t know if I was literally thinking about “Whitey on the Moon,” but I know I had been listening to that song a lot in that year or two surrounding this. So it was definitely subconsciously a huge influence on that song.

I wrote it so fast. It might have been after I wrote it when I looked at it and it’s like, Oh, yeah, “Whitey on the Moon.” But I’ve always been very outspoken about drawing the connection to that song because I think it’s an amazing song that tells a story with great economy and very few words.

EN: I agree! We’ve covered a pretty vast waterfront here, is there anyone we’re forgetting?

PH: The Silos should be mentioned. They’re kind of an overlooked chapter in music history. Their album Cuba is a masterwork in a certain type of understated writing that was a huge influence on me. Like DBT, they were a band with two songwriters, both of whom I would say were extremely formidable. They had a song called “Commodore Peter”—it’s a really great song that implies a great story without telling it. You know somebody got killed but you don’t really quite know exactly who or why or how. It just sets the scene. They were really good at painting pictures. The story kind of came from how you looked at the picture.

EN: We keep coming back to this idea that the best story songs are left ambiguous. I think that’s interesting. Do you remember the first story song you attempted?

PH: I think my first attempt was “The Fireplace Poker,” which didn’t come out until 2011 on Go-Go Boots, but predates Drive-By Truckers by a number of years. I can’t remember if I still was in Adam’s House Cat when I wrote it, but it was right before the end of that band. I spent a long time writing and rewriting. It’s a song about murder, and there’s so many ways you can look at that.

EN: For sure. Two sides to everything.

PH: “The Fireplace Poker” was the true story of a preacher taking a contract out on his wife and then the guy he hires to kill her does a bad job and botches it. He comes home expecting to find her neatly shot, and instead she had been stabbed multiple times but was still alive, so he beat her to death with a fireplace poker. He ends up killing himself, although there might be some question as to whether he actually killed himself or whether maybe a family member did. It’s a pick-me-up. And not the simplest story to tell, but that’s what I was fixated on in that moment.

EN: I love that song. It reminds me of Nick Lowe’s “Mary Provost.”

PH: I have to tell you one more thing. I want to talk about your new single “Print the Legend,” which I love. I love the reference to John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. I love that it’s five verses that cover thirty years.

EN: Thanks, man! I was trying to conjure all of my writing heroes, from Charles Portis to Joe Ely to you. It was my first effort at having a song that included a body being pushed out of a vehicle and I’m pretty happy with the ultimate result.

Listen to all of the story songs discussed here (and a few more) on “Print the Legend”: A Playlist.

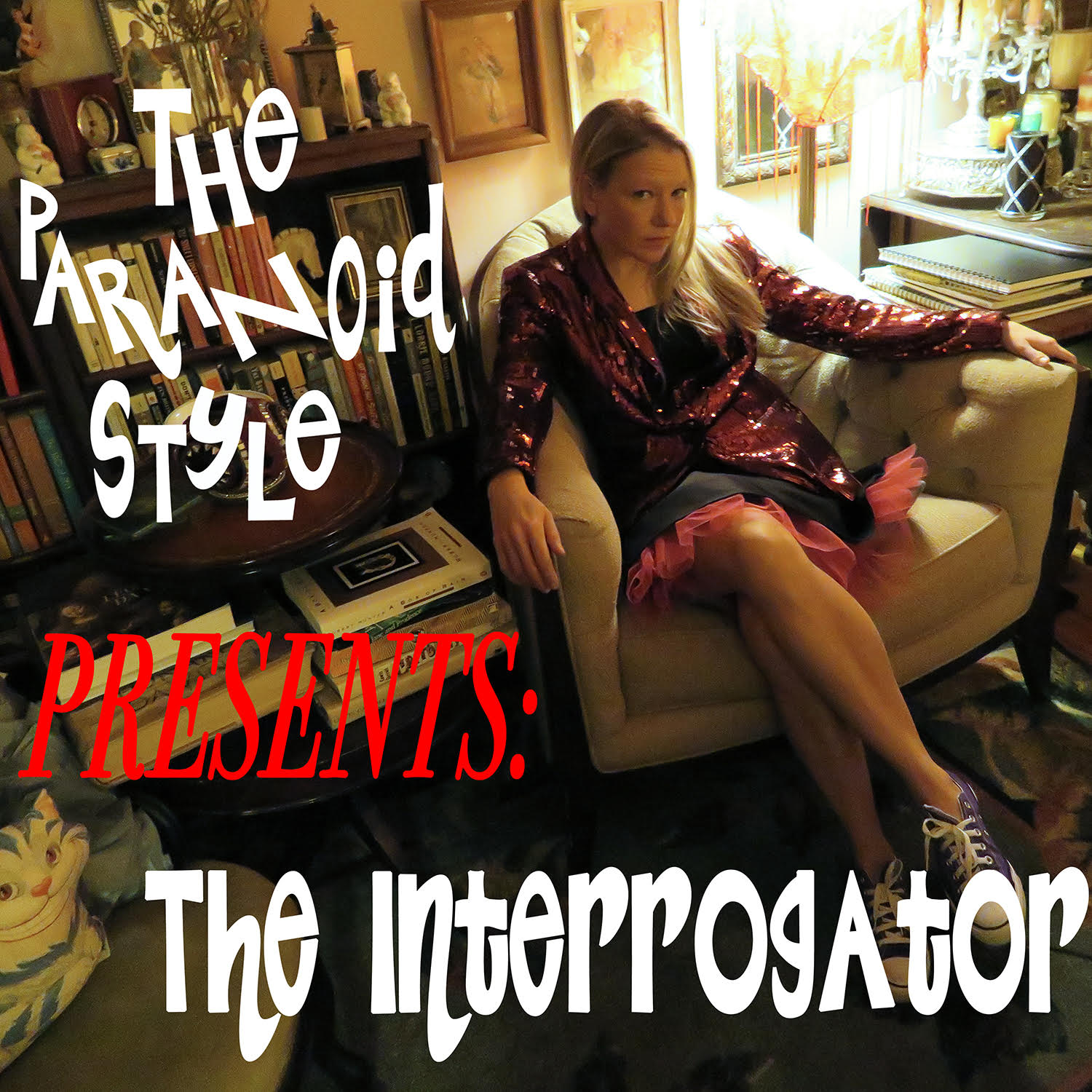

Elizabeth Nelson is a DC-based journalist and singer-songwriter in the band The Paranoid Style. Her new album “The Interrogator” will be released on Bar/None Records in February, 2024.

More Interviews