Jericho Brown is not only a Pulitzer Prize winner but a poet’s poet. The first time I was introduced to his work, it wasn’t even a poem. It was a group of friends ranting about form in the middle of the night. They were poets, and passionate about claiming everything that came with the word, because they knew what naming things could create: worlds. New and ancient. Present and futuristic. They used Jericho Brown as an example. Mentioned a poetic form called a duplex, which Brown invented. And as someone who was solely writing personal essays at the time, I smiled at them smiling and couldn’t help but to envision a building—the one my father lived in around the time I was ten and we’d walk to the corner store for crawfish in the summer. My brain began to churn at the impression of an image.

Poetry informs our existence in ways we’re mostly unaware of until time passes and we can look back and say, “Oh, that’s who I am, and this is how I did it.” Most recently, Brown served as editor of How We Do It: Black Writers on Craft, Practice, and Skill—an anthology of essays and interviews from some of our most prolific storytellers on ways we can find our own pace within the deliberate race.

Over Zoom, Brown and I conversed on what it means to make poems while persisting within the merry-go-round of perception and process, and how to make intimacy your craft’s biggest ally.

Kendra Allen: When I started writing poetry, I was talking to a publisher, and the first thing they told me was we publish poetry for the love of it and you don’t make money. They framed poetry as a dying genre. They were really adamant about telling me to lower my expectations. Which got me thinking: Why do we always romanticize the starving artist? Since you’re someone who has subverted those expectations, I want to ask: What do you think are the risks and the advantages of romanticizing the struggle of the artist and art-making in general?

Jericho Brown: I guess some of the risks of romanticizing art-making seem to me just that you get into the person more than you get into the art itself. If you’re thinking about art-making, maybe that means you’re thinking about the painter, or you’re thinking about the poet more than you’re thinking about the painting or the poem.

No poem is exactly perfect. But poems don’t fail you in the same way people do. You can’t get into idolizing people just because they’re good at something—singing or writing poetry or playing basketball, or whatever.

At the same time, I don’t think we make enough of our endeavor. Part of what you’re talking about, if we move away from the financial aspects of things, part of what poets deal with is just shame. And I think it would do us well to be prouder of who we are and not approach the fact of us being poets with this idea that we’re somehow taking advantage of the world. I think that happens because people find out that we’re poets and they try to shame us. But the fear that poets have of that is much too great considering the fact that we know that poetry has indeed changed our lives and the lives of other people that we know. So we know it has power. I was telling a poet friend of mine that poems are from one to one. One poem reaches one person in the way that it reaches that one person. As long as poems are around, they are indeed touching people. They are indeed changing minds. We don’t know what poems do. We can’t quantify it, but we do know that they work.

KA: There’s that outside shame, but also the internal shame that poets deal with on the page, which makes me think of the revision process. Sometimes it can take years to get the final draft of a poem—sometimes a day (it all depends on what you’re writing). What is your relationship to letting go of words from the first draft to the final draft? What, if anything, sticks from that first draft to book form?

JB: A lot stays, a lot goes. It’s different for each poem. Some poems start out two pages and end up fourteen lines. Other poems start eighteen lines and end up nineteen lines. You just don’t know what’s going to happen.

You have to be indifferent toward what happens. You have to want to have poems, you have to work on your poems, but you can’t get wrapped up in trying to keep a line or a few lines. The important thing is that you have the best poem that you can possibly have. And so you just work on a poem and if it looks nothing like it did in its original form, that doesn’t matter. The point is to have a poem.

I don’t really even notice when I’m cutting lines. Now sometimes I’ll cut a line from a poem and paste it on the side to make sure I have that line, because I might be able to use it somewhere else. But other than that, I’m not counting lines or worrying about taking lines from a poem. I don’t have any affection for one line over another, really.

KA: When you cut them, do you keep them, thinking, Maybe I’ll need these later? Or is it just, Put them in trash.

JB: I think everybody should keep everything. You don’t know what you’re going to need when you’re writing a poem. And sometimes if you’re writing a poem in 2023, you get to a point where you need lines that you wrote in 2003. And when you get to that point, those lines need to be somewhere you can cut and paste them.

KA: I didn’t learn poetic form per se in college, but I did take classes in fiction and nonfiction, where I was taught all these rules. And I remember thinking, Everybody in this class is going to sound alike if we follow all these rules. So when I think about the duplex poems—does that come from you knowing and learning and studying form in order to feel safe enough to bend it? Do you think it’s best to learn form and then break the rules? Or does form hinder you when you’re trying to innovate and do your own thing?

JB: I think it’s a good idea to know everything you can possibly know about what you claim to love. If you have a passion for something, then you should know everything there is to know about that thing. And I have a passion for poetry and poetry resides in form. There’s no way around that. Because every time you have a poem, you either have to speak it aloud, or you have to write it down. Once you write something down, once you’ve spoken it aloud, you have indeed made clear its form. You end up with some sort of formal concerns whether you like it or not. So you might as well like it.

The more you read formal poetry, the more you understand the kind of work form can do. And that gives you some examples of exactly how you can make use of whatever form you’re writing in. And once you know what the forms are, you can subvert them, you can experiment with them, you can turn them on their heads. But if you don’t know them, then you don’t have the same opportunity to do that kind of work.

Whenever you write a poem, you’re not just making a new thing. You’re also making a comment on everything that has been written before it. Poems grow out of all the other poems ever made. When I write a formal poem, I’m making a comment on the past of form, on all the ways that it hinders us and all the ways it helps us. So poems can show us what progression looks like.

KA: I hear you on that. Do you think those comments are conscious? Are you conscious, as you’re working through drafts, of what the poem is in conversation with or an extension of, or does all that come later?

JB: Well, it depends. Sometimes you’re conscious of it and sometimes somebody points it out and you think, Oh, I didn’t even realize I was making use of this other piece of literature. Because some things are so deeply ingrained if you’ve read them enough. They’re so deeply ingrained, you have no choice but to reference them.

Sometimes when you’re writing a poem, you can have a draft done, and reading the draft lets you know where the poem needs to go. You read the draft and you realize, Oh, I should add this thing about The Odyssey. Or I should push this toward these lines that are repeating in a certain way. Maybe this is a villanelle. Sometimes that happens at the end and sometimes that happens while you’re at the beginning of writing the poem. And it’s different every time.

KA: It’s rare that a poet is just as effective on the stage as they are on the page. But you are one of those people. I keep going back to the process, but is this something that you’re aware of when writing—how the words will sound out loud, the rhythms, the pacing, or how you perform a line break versus how you break a line in visual form? It’s almost like becoming a rapper.

JB: I think about all those things and I don’t think about them at the same time. I do want to take care that the line breaks are somewhere in my voice, but I don’t want to overenunciate them. I also think it’s a good idea to try. Sometimes people give a reading and you can tell they’re not really even trying.

When I’m reading a poem aloud, what I try to do is read it as if I am talking to someone. I want the poem to feel like a conversation—a very intimate conversation but a conversation nonetheless—between two people. So when I’m reading a poem, one of the things that I imagine is that I’m talking to one person all the way in the back of the room. And no one else is in the room, just me and that one person. I think about how I would talk to that one person as opposed to how I would read to an audience of people. Those are things that have helped me, if I’m helped at all, with public reading.

KA: Do you have anxiety before reading?

JB: Yes. I’m usually sick before I give a reading—to the point of throwing up. I get very, very nervous. I start sweating, I start fidgeting, and it’s good for me to get up there and open my mouth and just start talking. Then I calm down as I go, but usually right before, it’s hard. But if I can get going, I’m all right, and then I really love it when it’s over.

I don’t mind reading because I always understood that I would have to do it. I can’t imagine a world where that’s not part of what I do, even though it’s not necessarily my favorite thing to do. At the same time, I do love Q & A. I love when people ask me questions. And I love the opportunity to know what I think. Sometimes you don’t know what you think until somebody asks the right question. Then when they ask you that question, you have to answer it as honestly as possible and you find out what you think when you answer.

KA: Do you like attending readings?

JB: I love readings, actually. When somebody’s written really good work, I think it’s beautiful to hear people read. The problem with readings is that you don’t always know that they’re going to be good. But when they’re good, they’re so worth it.

KA: Your writing is simultaneously Southern, Black, and queer, and you work within those intersections very overtly. How does it feel when you’re writing Black, Southern, queer work and White people are reviewing it and commenting on it?

JB: Honestly, I’m always surprised that White people are as interested in my work as they have been. Especially early on as a writer, part of my fear of saying certain things had to do with ideas that I had about race that were inherited ideas. Sometimes it can be difficult for Black poets if you have this idea of yourself as a representative of the race. The question then becomes: To whom are you representing the race and why is what they think so important? And if you’re worried about what other people think, then you’re not able to be honest. You’re trying to be impressive. Which isn’t always a good thing as a poet because you can’t be vulnerable and impressive at the same time.

For me, it’s good not to think about those things so I can focus on writing the poems that I need to write. I just have to tell the truth about that intersection—Black, Southern, queer, and whatever else—that those are the real intersections of my life. That’s what poems show us: they show us just how complex a life is. Poems are complex in the way lives are complex. Lives are not about any one feeling. Poems are not about any one feeling. Poems are always about many feelings.

People who are different from me are welcome to read my work because that’s what literature is for. It’s supposed to help us see who we are by showing us facets of ourselves that we don’t know or don’t expect, and in order to do that, you have to be reading work by people who are not like you. So I don’t have any trouble with people who are not exactly like me reading my poems. I expect it. I grew up reading poems by White people, so I don’t see why they wouldn’t be reading poems by me.

I will say this. Much more than I think about those who are not like me in some way, I think about those who are like me in some way. If I give a reading, I’m always happy to see Black people in the audience—like, Oh, look—Black people came. In particular, there’s a way that I feel a kind of duty or responsibility to be there, at least in presence, when it comes to Black queer people.

KA: How do you know when you’re not telling the truth in a piece?

JB: I think it’s good to be a little nervous, to feel a little queasy, to be a little uncomfortable while you’re writing. Not too much but enough to know that you’re in uncomfortable terrain. If you can sustain that feeling while writing, if you can lose your mind toward language such that you don’t really care what you’re saying, you’re much more interested in how it sounds—if you can hold on to that for long enough, then you end up saying things you didn’t expect to say. And you end up saying things that you would not have said if you were not writing a poem.

KA: Do you work in motion or stillness? Are you one of those people who need to be out in the world, living it? Or do you need to be locked up in the room, stressing until you get it done?

JB: When I’m working on a poem, I just need to be sitting down somewhere working on a poem. It’s nice if it’s quiet. If it’s not quiet, I have headphones and I can listen to the ocean or whatever. And it drowns out the sound and then I can work. But I also think I’m working on poems all the time, even when I’m not sitting in front of a computer. I try to live as much life as possible. I want to fall in love and dance and hang out with my friends. I want to do all that stuff. And the more I do that, the more I have something to write about.

KA: Is there a topic that you wish to touch on in your writing that you haven’t, or a topic that you wish to move on from that you can’t?

JB: There’s nothing I wish to move on from. If I’m still dealing with something, I have to take that as a good thing—the poems are working it out and some things take longer than others. And it’s always good to write new poems about old themes because your perspective on those themes will continue to change the older you get. How you feel about your family. How you feel about your father at the age of thirty and how you feel about your father at the age of fifty are going to be two different things. And you’ll be a poet when you’re thirty and you’ll still be a poet when you’re fifty.

There are a lot of things that happen that I always hope will end up in poems. Right now, I think—I don’t know—but I think I’m writing a book about gun violence, popular culture, and television. And I would like to write some more poems about those things.

KA: Something you said that hit me is the peace you have around your process. I think it’s important for writers earlier in their careers to hear people say that it took time, that it’s time-consuming. Because we try to rush it. We think we’re on a timeline, but like you said, writing actually takes a lifetime. How long did it take you to have peace with the process? Did you struggle with that?

JB: As a kid, this weird thing happened. I was in church and I remember hearing about praying for certain characteristics for yourself. Like patience, for instance. People would say, “Oh, if you pray for patience, then you’ll go through situations that make it hard for you to be patient. And that’s what’s going to build up your patience.”

KA: Did you grow up Baptist?

JB: Yeah, you know how Baptist people be saying crazy stuff like that, and I’ll never forget this. I remember being a little kid and hearing that. And I remember thinking, Oh my God, I just need to be patient. I don’t need to be in a position where I pray for it because if I pray for it, then it’s gonna be worse. So I decided when I was a kid to just be patient. I was so afraid of making it worse. If I was in a situation where I had to wait, I wanted it to be okay that I’m waiting. In order for it to be okay that I’m waiting, I can’t trip. I just have to think about something else.

Things take time, but so what? It’s better to have good and beautiful work. It’s better to have made something that you can be proud of, that you can be excited about. It’s better to do that than to just be putting stuff out here in the world because you’re impatient.

KA: You edited a new anthology, How We Do It. Is there something from another writer’s practices that you’ve adopted and incorporated into your own?

JB: One of the things that I learned is from Daniel Black’s essay. He taught me to pay more attention to how I use Black vernacular and really do everything in my power to make use of Black vernacular in every line. To make sure that the poem gives you the sense of a particularized person speaking. And since the speaker will come from my point of view, of course that person will be Black.

Another thing that I learned is from Rita Dove’s essay, and that is to be able to let go of what I think a poem is and to understand that when I’m writing a poem, I’m always making a new thing. I’m always changing what poetry is. So putting that book together was indeed very useful to me. And I’m glad I did it because I feel like it’s the greatest gift I will ever be able to give to new and younger writers.

KA: I always say I think a class should be taught on how to sequence a poetry collection. Sometimes that feels like the most dire part of the storytelling. What is your approach to sequencing a poetry collection? And what are the similarities and differences between sequencing poetry and sequencing, say, the anthology?

JB: The anthology was about figuring out the themes. I found a way to make the essays open into one another. Someone would drop a hint about something in one essay, and that hint would be the topic of the next essay. I wanted to open things up so that each section becomes its own little tome or its own small book within the book.

When I’m putting poems together, I do something similar. I try to move associatively from the final line of a poem to the title of the next poem. Which I think helps keep readers inside the book. And I try to make resonance happen. I put subjects throughout a book. For instance, the way that the duplex poems don’t appear next to each other. Instead I scatter the forms throughout the book. I try to structure it so that when something comes up, it comes up again a few poems later. Themes go away and come back and go away and come back and intermingle with other themes. I think of a book as a world of ricochets. ![]()

Kendra Allen was born and raised in Dallas, Texas. She loves laughing, leaving, and writing Make Love in My Car, a music column for Southwest Review. Some of her other work can be found in, or on, the Paris Review, High Times, the Rumpus, and more. She’s the author of a book of poetry, The Collection Plate, and a book of essays, When You Learn the Alphabet, which won the 2018 Iowa Prize for Literary Nonfiction. Fruit Punch, her memoir, is out now.

Jericho Brown is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award and fellowships from the Academy of American Poets, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Brown’s first book, Please (2008), won the American Book Award. His second book, The New Testament (2014), won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. He is also the author of the collection The Tradition (2019), which was a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award and the winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

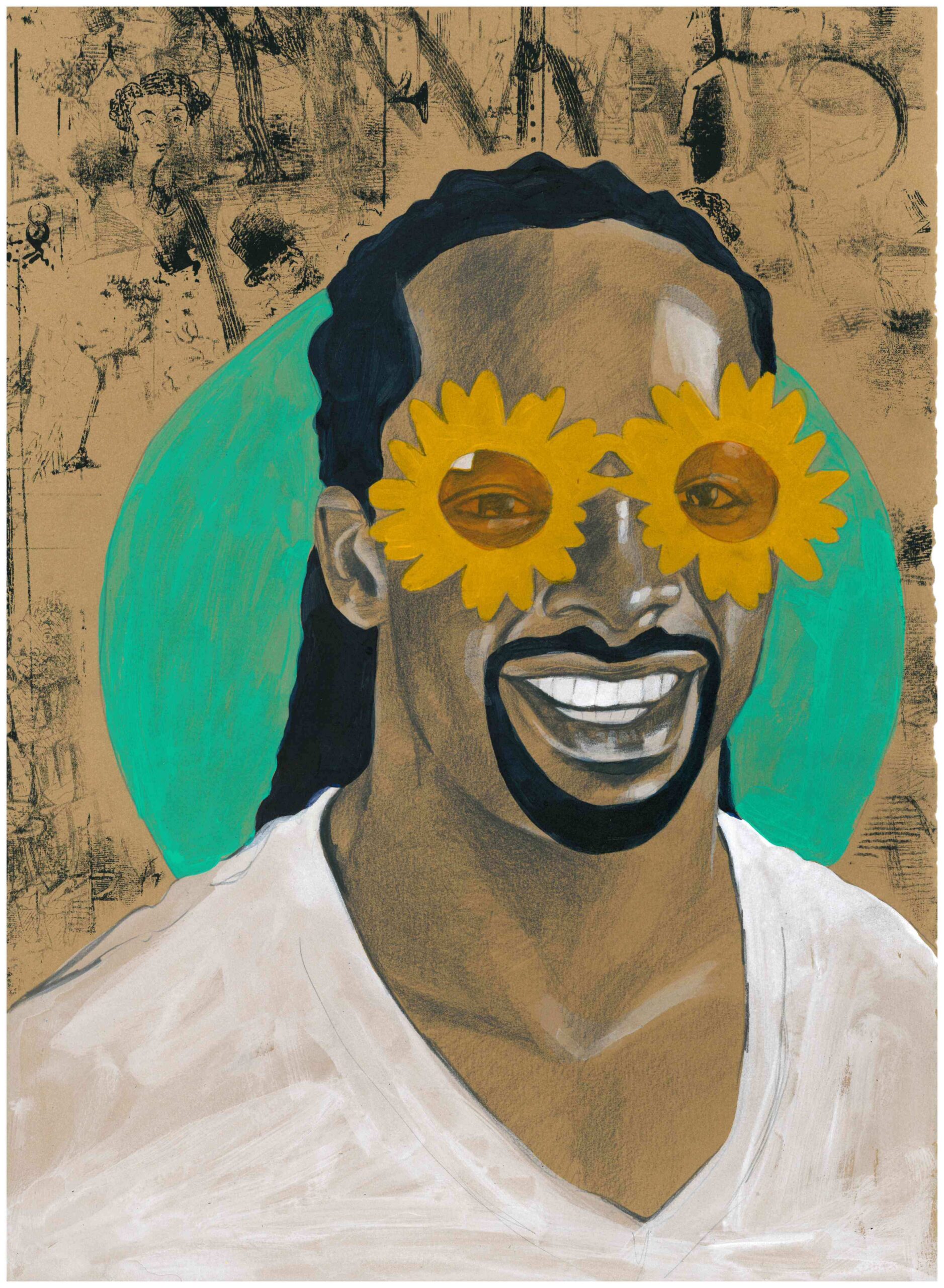

Illustration: Vitus Shell