For months we tended the wounds of our men, our brothers, our fathers, our friends, husbands, boyfriends, and lovers. We bought iodine and gauzes, cotton and rubbing alcohol. We made patches, slings, and casts using socks, scarves, and odd-shaped branches. The hairs on our backs stood at the sight of knifed flesh and burnt flesh, broken bones, exposed bones, and bullet holes. Red, white, and the smell of copper. We gagged. We swallowed. We breathed heavily, grinding our teeth, trying to appear unmoved and unaffected. Disappointed, perhaps. Instead, such sights inspired us. It made us angry. Rabid. Bravas. Bien bravas. But not less afraid. Fear, we found out, is not the absence of courage. Suddenly we realized that we had memorized the hospital’s many wings and hallways, that we could find an exit with the lights out, and often we did, whenever the police came looking for us: las ánimas. That’s what they called us because people thought we were ghosts, because at first they couldn’t find us, they failed to catch us. We were too slick, too astute, too innocent, and inoffensive, and we watched the city change. Policemen aimed their rifles at anyone dressed in black. They left their stations and scattered around the city on top of angry horses. Police guarded the Palacio Nacional, the cathedral, Teatro Lux, La Casa Crema, El Cairo, Kaffee Dieseldorff. They hid between bushes. They peeked inside windows. Hired informants. They paid maids, tailors, seamstresses, nuns, and barbers to be their informants. They trained spies. They dressed as vagrants, but people soon realized they were spies because the president would never allow vagrants in his city. They slept in attics instead, and some of us fed them and gathered information for them but truly learned all about them—their sleep schedules, what types of guns they favored, where they lived, their food allergies—and passed that information to the resistance, or used it ourselves. One time, one of us finely minced half a pound of peanuts, put it in a broth, and gave it to a pair of government spies. One had to be rushed to the hospital and nearly died from anaphylaxis. He didn’t though, and then blamed his cook. So the cook, our sister, was forced to leave the country. Many of us did. Others couldn’t. No les dio tiempo. No nos dio tiempo. The police grabbed many of us. They arrested us. They took us to the Palacio de la Policía or San Ramiro on 8th, where, surprisingly, or perhaps unsurprisingly, we found many of our missing men half dead, starved, bashed, and battered. Reunions, we found out, are often bitter and painful, like chewing fresh chichicaste. And so they tortured us too. They beat us using varas de membrillo and rubber batons. They hung us by our thumbs and whipped our backs. They tied us to a rack and stretched our limbs. They dropped us naked on quicklime. They rolled us on quicklime and made us chew quicklime and fresh chichicaste. They touched our breasts, they pinched our nipples, they burnt our nipples using cigars. They raped us. They tied us to a rack and raped us. “Ya vio que no fue tan feo,” they said. “Para mí que le gustó,” they said. “Ay, ¿pero y por qué tan seria? Ríase, hombre. Eso le pasa por puta,” they said. Then, after a few days, a couple of weeks, or several months, a bunch of papers would appear in our cells. They would tell us we could leave if we signed the papers. “Una firmita y a la casita.” Some of us read the papers. Others didn’t. No pudieron. No pudimos. They didn’t let us. They put our names on the papers. In them, we—but truly, they—framed innocent people. In them we—but truly, they—told stories about orejas and communist spies. In them we—but truly, they—swore loyalty to the government. “Una firmita y a la casita.” Some of us signed the papers. Others didn’t, and we never saw them again. This made us angrier. Some of us left the country. Others became even more engaged, more involved. Students. Nurses. Teachers. Mothers. Daughters. Housewives. Widows. Us. All of us lived in fear. Todas. Some of us kept quiet, hid indoors, and tried to appear feeble and sick outside. We wore hats and veils and scarves outside. Others gave off an air of indifference but secretly helped draw maps and held meetings, and hid people in our houses. Still others bought rat poison or learned how to make rat poison and carried tiny bags of it, and one of us successfully poured rat poison into a police officer’s cup and cried when she heard that he had died.

We joined groups others had established way before most of us had even been born, groups made for us. El Sindicato de Maestras 1927. Las Señoras de Mazatenango 1922. El Círculo de Estudios Teosóficos Helena Blavatsky. La Fraternidad Espírita Guatemalteca. La Sociedad Gabriela Mistral. We wrote poems and essays. Novels. We prayed. We lit fires. We cast spells. Hicimos limpias. We learned shorthand, Morse code, and Braille. We learned sign language and became fluent in Jerigonza. We learned English and Deutsch. We taught others our native languages. K’iche’. Kaqchikel. Mam. “Ma tzoq yal jun spik’b’il pax toj tjaya.” Some of us didn’t, though. Some of us arrived at the city, and the heavy cloak of discrimination darkened our days, and so we bit our tongues and spoke only Spanish, Castilla. We folded our güipiles, put them away in a valise, and did not take them out again for years. Some of us could write a thousand words on a tiny piece of paper and often passed or received messages that way. We did this at Parque Jocotenango, at Jardín de la Concordia, at Parque Central. We did this in broad daylight, on 6th Avenue, or in the middle of the night, by the ravines near Barrio Gerona. We did this and then burnt the messages or ate them. Some of us developed infections from eating so much paper and graphite, and still we tended the wounds of our men. Like on April 23, when the police chased a group of students inside Cine Capitol and beat a young man in front of the screen, and left him there on the floor, and then one of us wiped the blood off his nose, used her scarf to stop the bleeding, found one of the man’s teeth underneath her seat, and even gave him some money. Or like on May 8, when a police officer tossed a man on the ground and kicked his face and his side, and then two of us hurriedly bought a bag of ice, put it on the man’s side, and helped him reach his house, and often visited him. Or like on May 14, when one of us walked out the door and found a man unconscious on the ground. The man was half naked and had cuts and burns all over his chest and an eye swollen shut, and as soon as she touched him, the man woke up and started screaming, “No, no, please, no more, please.” She dragged him inside, shut the door, cleaned his wounds, and cooked for him, and the man told her that he had escaped prison and that his brothers had been killed by a firing squad and that he had nowhere else to go. She told him to be quiet, gave him some of her grandmother’s clothes, and took him to a safe house near Avenida Elena. “You’ll be safe here,” she told the man. “It’s the only time I’ve ever been late to teach,” she told us.

And again on May 18, May 24, May 31, June 2, June 12, 13, 14. Or like June 18, when the police started using phosphorous bombs, and that same afternoon, a couple of us who worked as apothecaries in Farmacia Klée started handing out small bags filled with copper sulfate to neutralize the bombs and treat burns. Or like on June 23, when the president suspended civil rights, and the police first opened fire on civilians, in public, in broad daylight, and some of us dragged the wounded inside our houses and cleaned their wounds. The next morning, a small group marched down 6th Avenue with their hands behind their backs, and the police killed three men and injured many more. Some of us heard the gunshots, the screams. We saw the men running. Some of us saw the blood and the dead. One of us, a municipal worker, helped move the bodies and clean the scene and scrub the blood off the concrete floor and scrape it off the fountain to make it seem like nothing had happened, like Guatemala City was the finest, most cleanest city in Central America, la más mejor, and comparable only to other notable metropolises like Habana, Madrid, Buenos Aires, New York, and pre-war Berlin. And so we hid in our homes, and we told our brothers and sisters, and our parents, what we had seen. They told us to be quiet, and they closed the blinds. Others said, “Bueno está,” and “They ought to kill them all bien despacito, pa’ que les duela.” Still others said, “This wouldn’t happen if more women joined the marches,” and “The police wouldn’t dare to fire on an all-women’s march.”

We believed them, and each other.

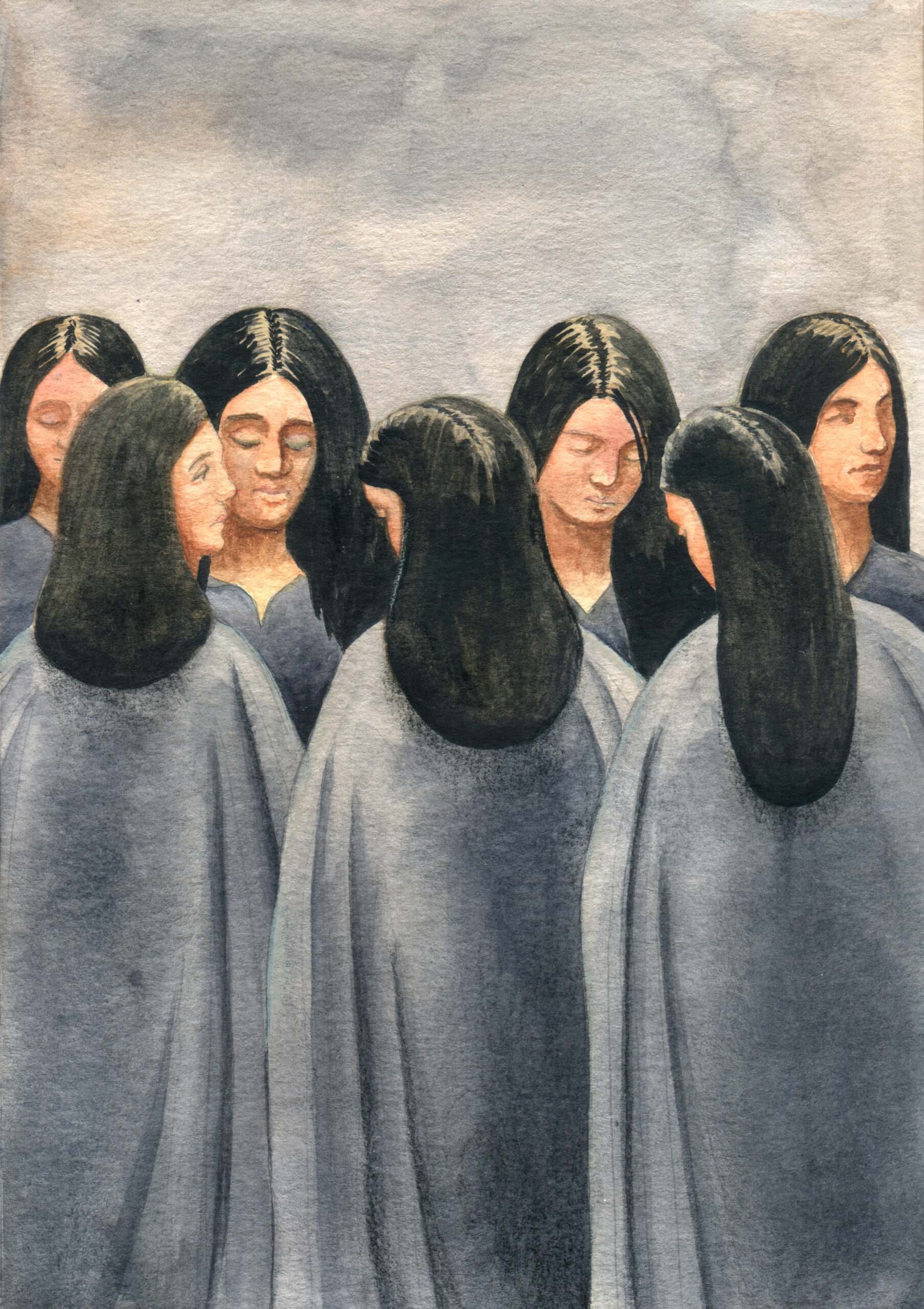

We gathered the next day on and around San Francisco’s atrium. We. Us. Las ánimas. There were hundreds of us, and we all wore black. Some of us had never seen that many women gathered all in one place, and so we sighed and got teary-eyed. A black river. A thousand-legged serpent, hissing, hissing, hissing. We saw the crowd grow larger. We saw people go by. People asked us what we were doing. “We’re mourning,” said one of us. “Estamos de luto.” We saw police officers looking at us, talking to each other. They said hi. They complained if we didn’t reply. They called us names. Creídas, they called us. Estiradas, gordas, feas, they called us. Putas, they called us. They clapped, whistled, howled, and hooted whenever the wind ruffled our skirts. “¡Viva Ubico!” they shouted, and they soon left, and so we carried on.

Five forty, and with the sun dripping down our side, we walked.

We walked south on 6th Avenue. We walked in silence. We looked up, proud and defiant, and we also looked down, downcast and afraid, worried. We looked around. We stared at the clouds, mansards, and pipes. At the trees poking out of Jardín de la Concordia. At the vines wrapping around the metal railings. At the shops closing down. At our friends and boyfriends who were at the side of the road. Some of us had heard others talking hours before the march, and we felt suddenly inspired to rush home and change clothes, and came uninvited and didn’t know what to do or say. Some of us had spent years organizing union workers and collecting signatures, and knew where to punch, and how hard, and even how to outrun a horse. Some of us covered our faces, removed our rings, and even faked a limp to alter our gait so that people couldn’t identify us. Some of us wore our veils around our necks and aimed our sharp chins up front. We knew each other by name. Blanca Urrutia. Carlota Silva. Berta de Corleto. We introduced ourselves as our parents and grandparents taught us. We shook hands. We hugged. We kissed each other on the cheek. Both cheeks—one of us had lived in Italy. Lilián Aguilar. Adriana Solís. Some of us wore hats and shoulder pads. Some of us had never gone to a funeral and had no black clothes, so we borrowed, took, and stole from our friends, sisters, mothers, and neighbors. Elena Irigoyen. Beatriz Irigoyen. María Consuelo López. Some of us had to ask permission to leave the house. “I’ll be at Funerales Bianchi on 12th,” one of us said. Or, “Remember I told you about my tía—Tía María? Today marks the twentieth anniversary of her death. We’re going to the cemetery to pray. Do you want to join us?” another one said. “No,” he said. “But bring some food.” Raquel Solís. Elena Robles. Margarita Carrera. Some of us pretended to be ill, locked ourselves in our rooms, jumped out the window, and ran shoeless to meet our friends. The parents of some of us gave us their blessing, told us how brave we were, and said a quick prayer as they opened the door for us. María Barrientos. Laura Zachrisson. Luz de Silva. Some of us were still working by the time the clock struck 5 p.m. and had to take a bus and the tram, push through the crowd, and run to reach San Francisco on time. Graciela Quan. Gloria Menéndez Mina. Luz Méndez de la Vega. One of us was from Colomba Costa Cuca and always said it was too hot in the city. One of us was from Paquilá and always said it was too cold in the city. One of us was from Cuilapa and told people she had seen the devil one night crossing the local bridge. “Olía a azufre,” she said, “y no son cuentos.” Some of us had failed to get used to the city’s bustle, but still we told people that we liked living in the city. We didn’t. We missed our mountains and our rivers. We missed picking hail off the ground. Chita Ordónez. Ester de Urrutia. Blanca Ofelia. Some of us had lived in the city our whole lives and saw when men poured cement over the dirt and shaped it with some wooden planks. Then we memorized every crack on the ground, every hole and slump, every pit, and knew where to stand, which manhole covers moved and made noise if you stepped on them, which side to take when riding a bicycle, and where to find the freshest cashew, the sweetest sweetsops: en el mercado de Gerona. Olimpia Porta. Elena Navarro. Some of us had lived abroad and talked with a weird accent. We were there. Teachers walked alongside students. Mothers. Daughters. Sisters. Nurses. Factory workers. Writers, poets, and scriptwriters. Angelina Acuña. Elisa Hall. Julia Esquivel. Adriana Saravia. Young and old. Teenagers. Patojas. Some of us had not yet begun to bleed. Others had stopped bleeding. Still others were pregnant with their first child, their second child. One of us was expecting her fourth child. Still, we walked. We were afraid, we were uncomfortable, we were nervous, hungry, and anxious. We clenched our teeth. We swallowed hard. No one said a word. Some of us walked absentmindedly, as if in a daze, quietly staring at the shoulders in front of us. Elena Sáenz. Clemencia Rubio. Irene de Peyré. Some of us remained focused on the side of the road. We stared at the people on the side of the road. Suddenly, people started clapping. They cheered us. An old woman reached our side, smiling and clapping. She touched our backs and watched us go by. “Vayan, patojas,” she said. “Don’t be afraid. I wish I were like you. We should all be like you: bravas y valientes.” María Albertina Gálvez. Elsa Barrios Klée. People opened windows and stepped out on the ledges, waving black cloths, rags, and scarves, banging on pots and pans. A small man stood before us and called us comunistas, putas, and threatened to kill us, but a small crowd grabbed him, tossed him to the ground, and people again cheered. They laughed. We smiled. We felt strong, as if we could move a mountain, as if change was within reach. María de Ashkel. Rosa Castañeda. Aida Chávez. One of us stepped on a manhole cover, and it moved, and the manhole burped, and we felt like we could split the ground, like our feet could cause a tremor, an earthquake. Como si de un zapatazo fuéramos a poner el país patas arriba. Elena López. Ofelia Castañeda. Margarita Crespo—

Then we saw the horses.

A group of men on top of horses appeared on the corner of 6th Avenue and 17th Street. They grabbed on to their saddles. They unsheathed their sabers. They pulled out their guns. They: dolled up and vain, vulgar, half-lit, and with grave faces, dead eyes, and calloused hands, and soon the clouds parted, and we blinked. It was as if they had roped the dimmed sun, carried it like a kite, and hung it just so, in the sky, to blind us, to blend with each other’s shadows and appear larger, more grotesque, to confuse us. A nightmare. Ogres and horses. A Fuseli painting.

“Ay, vayámonos, patojas,” one of us yelled, looking around, “they’re going to kill us.”

We slowed down, and the river’s firm water suddenly trembled. Some of us moved aside and looked back at the rest as if waiting for endorsement or an accomplice. Rosa Luna. Estela Zúñiga. Ángela Porras. But before we could react, the ogres leaped onto the ground and they started firing at us and chasing after us. They dropped bombs on us, and the white smoke filled the street. We screamed and ran away from them. We hurried each other. We yelled at each other, told each other, “¡Corran! ¡Corran!” and “Don’t look back!” We ran inside shops and helped people close the doors. We watched them shoving the old woman who had greeted us to the ground. They, the ogres and horses, the brutes, like rocks from a landslide, split the river. Some of us ran back on 6th Avenue. Others hid behind pillars, coughing. Still others reached 16th Street and ran east, toward 7th Avenue, or west, toward 5th, amid smoke and gunfire, and saw people running also. We saw friends and relatives urging us to run, to run faster. The screams of terror turned into screams of pain. Their bullets found our arms, our thighs, our hands, and we fell to the ground and saw blood on the ground next to us, our blood, someone else’s blood. Dolores Gallardo’s blood. Soledad Samayoa’s blood. Ella Alfaro’s. Sally Rau’s. Cristina Paniagua’s. Julieta Castro de Rolz’s. Esperanza Barrientos’s blood. We felt the taste of copper in our mouths. We cried. We couldn’t breathe because of the smoke or the shock, ¡sepa Judas! But they didn’t stop. The ogres, they grabbed our arms. They ripped our skirts. They clubbed our heads. They put their boots on our necks and threatened to kill us, to rape us, to take us to a torture chamber. Our veils, scarves, and big hats fell softly like birds clapped in midflight. Our coarse voices got mixed in with the sounds of boots and bodies dropping heavy on the ground. We yelled. We cried in pain, but the police kept firing at us. A couple of us tried to free the others. We bit their hands, we scratched their faces, we punched, kneed, and kicked. Elena Ruiz. Julia Menéndez. María Silva. But they were stronger than us, more violent. They pushed us. They sat on top of us and clubbed our heads until we fainted, and they still kept hitting us. “¡Déjela, maldito!” one of us shouted. “¡Me la va a matar!” Guadalupe Porras. Hortensia Hernández. They broke our noses. They broke our fingers. They never stopped firing at us. We were on the ground, and still they kept firing at us. “¡Ay, Dios!” one of us shouted. “¡Mataron a Mari!” We turned. “They killed Mari!” We saw her, María Chinchilla, on the ground, with a single bullet hole in her right cheekbone. We tried to grab her arm, but they kept firing at us. A man wearing a gas mask raised his rifle. A nightmare. A Hans Larwin painting.

Julia Urrutia. Dominga Álvarez. Aida Sandoval. Elena Rodríguez. Julia Paiz.

![]()

Five a.m. Twelve hours later and our blood was still on the ground. No one had picked up the things we left behind. Our hats, shoes, bags, roses, and prayer books remained there on the ground, wrinkled and disheveled. Some of us got together in Jardín de la Concordia, again, in the morning, and walked across the scene and saw broken glass and that shops and businesses, schools even, remained closed. We saw no police out on the street. We knew better than to trust silence, though, for it, instead of being a sign of peace, often precedes cruelty. So, we waited. Isabel Foronda. Zoila Luz. Victoria Moraga. We waited by the church. On the streets. We waited as we watched people shyly step out of their houses. We listened to the radio, and we waited. We waited until we couldn’t wait anymore. Some of us went to check on the injured at the hospital, and a doctor told us that one of us was at risk of losing both legs. “The bullets shattered her bones,” she said and told us that another one of us had lost an eye. Some of us went to check on the injured and offered to volunteer at the hospital. María Jeréz. Alaíde Foppa. Some of us had hidden inside at a friend’s house when the shooting began and got arrested as soon as we stepped out—silence often proceeds cruelty.

Some of us returned home after spending the night inside Teatro Palace only to find out that the police had identified us and retaliated by arresting our brothers. Rosa Soto. Laura Pineda. Dora Franco. Some of us prayed. A few of us put a curse on people. Did rituals. Talked with the dead. Some of us wrote poems. Yo no tengo miedo a la muerte. Conozco muy bien su corredor oscuro y frío que conduce a la vida. Tengo miedo a esta vida que no surge de la muerte, que paraliza las manos y entorpece nuestra marcha. Some of us went to the factory and were stripped, searched, held in tiny rooms, released, and told we were not allowed to work until we could prove that we didn’t take part in Sunday’s march. Some of us were outside when the police came out again on top of horses and holding megaphones that they used to tell the people that the president had declared martial law and established a curfew. Still, we shouted and called them names. Romelia Alarcón. Magdalena Spínola. Tatiana Chuc. Again, we watched the city change. We saw people looking over their shoulders. We saw broken glass and empty streets. From our roofs and out our windows we saw the police beating people up. From our roofs and out our windows we saw towers of white smoke reaching for the sky. We heard gunshots. The protests never stopped. Some of us went out, looking for food. Despite our cuts and bruises, despite the fact that we had not stopped coughing, some of us went out again to protest. Some of us went to Mari’s funeral. Some of us remained indoors and talked over the phone. Some of us met in Plaza Barrios or near the Hipódromo, but no one dared to go near 6th Avenue. Puro cementerio parecía la ciudad. Silence, we heard, and it spread like a giant squid over the city, across its many plazas, and around the shoulders of those of us who still dared to go outside, and the squid, el calamar, grabbed us for days, for weeks, for months— That’s how they control us: with silence.

One day, one of us went out an hour before the curfew, rushed to the train station, bought a ticket, left the city, and crossed a border in the morning. She thought about calling her father, her lover, but didn’t out of fear. She ended up calling one of her mother’s friends and told her everything. Her mother’s friend promised her that she’d keep an eye on her father. She lived there, elsewhere, listened to the radio, painted every day, and, for the first time in years, felt truly free. María Antonia Velásquez. She inspired others to do the same, to leave the country. She inspired others to stay and fight.

On July 1, 1944, six days after the police killed Mari, and after days of public outcry, the president resigned. On March 1, 1945, we finally had a chance to cast our vote. ![]()

José García Escobar is a journalist, fiction writer, translator, and former Fulbright scholar from Guatemala. His writing has appeared in The Evergreen Review, Guernica, and The Guardian, and he took part in the 2024 Tin House Winter Workshop. He writes in English and Spanish, and has translated into Spanish ‘Solito’ by Javier Zamora and ‘I’m Not Broken’ by Jesse Leon, both for Penguin En Español.