The first time I saw the kid lurking around the block, the unreality he emitted made me uncomfortable. A few black and brown dirt smudges adorned his face. Faded fabric shreds covered and hung from his body. His feet seemed unaffected as he moved with agility through the labyrinth of trash, toxic puddles, and beer bottles discarded by the usual suspects: local alcoholics and “misery tourism” visitors. He’s a caricature, I thought. He looked like a child actor playing the role of a street urchin in a community theater play. Back when there were still community theaters.

I entertained the possibility that he might be an undercover snitch working for the cops. Perhaps they had sent him to El Barrio to identify drug dealing locations and rat out sellers and buyers. Or maybe his mission was to stand in front of clandestine abortion houses and let his lost childhood innocence—marred by a life of hardships on the streets—dissuade hurried girls from getting rid of the invader in their wombs.

I saw the kid for the first time on the same evening that I decided to stop smearing my body (from my forehead all the way down to the space between my toes) with drug cream. My instinct told me that this morning routine was fueling the constant drumming of my hemorrhoids. I was right. A few days later, with the hemorrhoids gone, the paranoia disappeared. Freed from it, I realized that my theories about the kid were absurd. Not even the police, famous for their negligence and stupidity, would be so negligent or stupid. The kid’s presence wouldn’t lead to repentance for those who had decided to visit an abortion house. It would have the opposite effect: the kid would allow these women to witness the most likely future of their unborn children. It would reaffirm that they had made the right decision. The kid was just a street kid, like most. Only that, nothing more. I saw him on every corner and every block in El Barrio. I never approached him. I am a lone wolf and have no interest in forming friendships or alliances. Much less with a minor. On the street, it’s more convenient to be alone. However, I must admit that I was curious to witness, from a distance, his street evolution.

![]()

From the sky, the Alps fell. The kid swapped his tattered shirt for a jacket, his shorts for jeans, and his bare feet were now protected by a pair of sneakers. I saw him shivering, indicating that his outfit was by no means designed for winter, but he would survive if he stayed away from the streets at night. I worried that he didn’t wear anything on his head—I myself have suffered the cold’s stinging attacks on my exposed ears and crown when they are uncovered. A few days later, I saw him better protected with a woolen hat.

I admired his resourcefulness. I saw myself in him when I was him. A street kid who cried upon realizing he was abandoned on a corner. A kid who only stopped crying when dehydration prevented him from producing more tears. A kid who adopted as a life motto the phrase his father repeated every time he took him on his nocturnal forays to La Periferia. The same one that his mother used when she forced him to hand down his old clothes to his younger siblings: “Things don’t belong to their owners, but to those who need them.”

![]()

In El Barrio, we agree that a quiet night is not one where the screams of terror, the sounds of blows, the splashes of blood, and the cries are completely silenced. Such a night has never been witnessed in the history of El Barrio, and no one expects it to happen. Here, a quiet night is when its noises, inhabitants, and events do not unfold in an endless succession but in a sporadic and unpredictable frequency. It is in the silent spaces of these quiet nights that I reflect.

“Things don’t belong to their owners, but to those who need them.” Thanks to this phrase, I dared to steal food and clothes to survive, as the kid does now. As a teenager I stopped calling myself Malte and became Iñaqui because I needed a new identity, and I assumed the one of the man whose wallet I took. Someone is the legal owner of this house, which can no longer be considered abandoned since I inhabit it; the need of a place to take shelter dictated that I could claim it as mine. I am, like the street kid is now, a borrowed man who has taken possession of what others owned by right of purchase and now belongs to me by right of necessity.

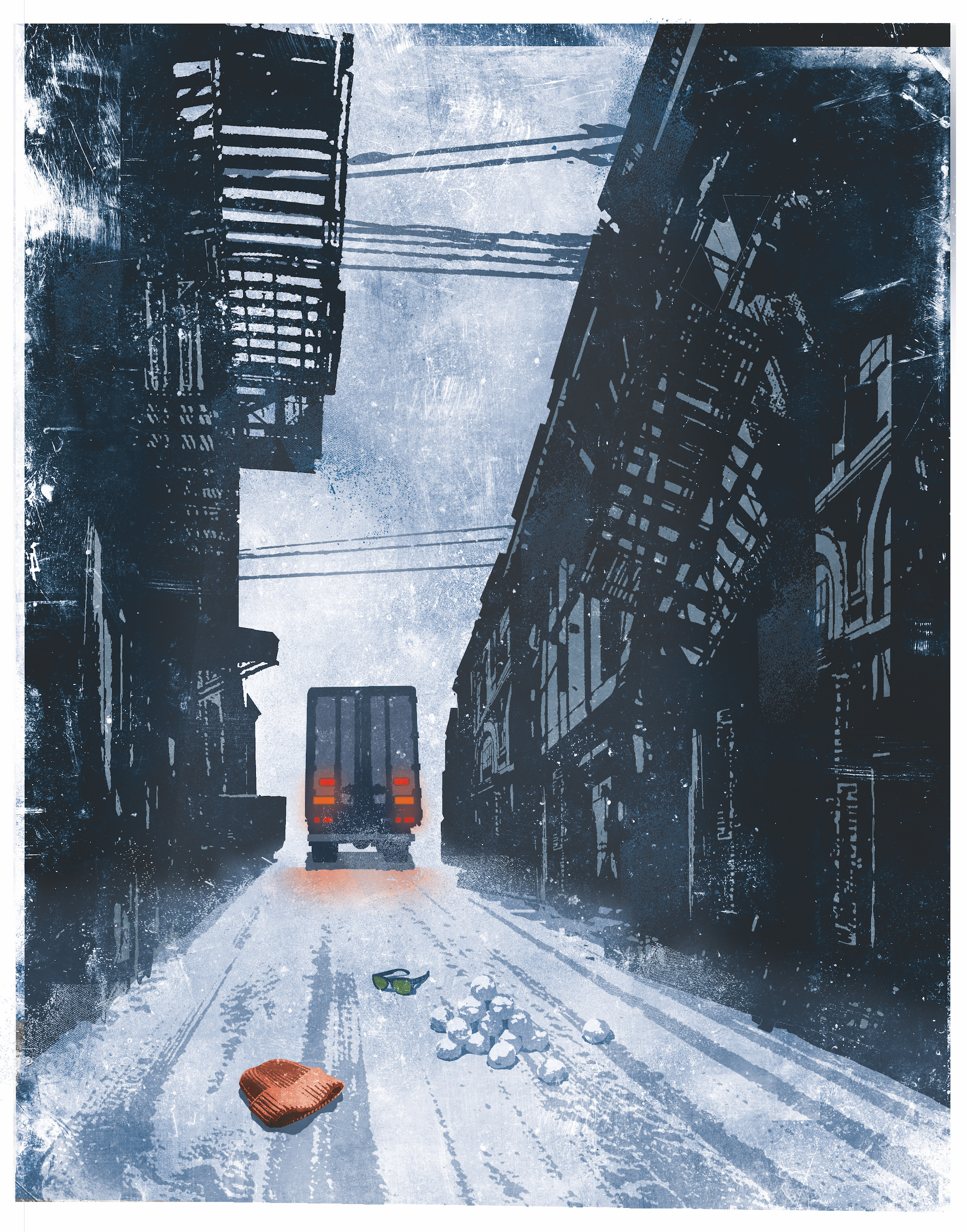

Today, the sun falls with a pungent force that irritates the back. I take refuge, then, on the comfort of my balcony. This chair in which I recline was here when I seized the house. I took the small table and the ashtray from the dumpster, which is a figure of speech because El Barrio is a dumpster. The kid is on the street. The weather forces him to continue wearing his winter clothes. Spring started two weeks ago, although the snow has refused to leave. It covers everything, from the bare treetops to the internal darkness of the sewers. The sunlight reflects off the snow and dazzles the eyes of any creature that dares to look directly at it. Hence, it makes sense that the kid has added a pair of sunglasses to his attire.

The kid’s custom is to roam, scrutinizing in all directions. Looking for opportunities. Detecting dangers. Not today. Today, he plays. He massages handfuls of snow into balls, which he then throws at a dead tree and its dead branches, and at the dead nests that hold only dead eggshells. I get angry with him; the street doesn’t give respite, and letting down one’s guard is not advisable. Spring must have lowered his defenses. I find it understandable. Despite his skills, he’s still a street novice. I want to yell at him that the street is not for playing. I refrain.

I also don’t warn him when I hear a truck turning the corner at full speed. It’s a cargo truck, the kind that never travels through El Barrio. The driver is, most likely, an apprentice. The police, although clueless when it comes to investigating murders and rapes, are ruthless when it comes to crimes against the inhabitants of La Periferia. And cargo trucks are exclusively meant for them.

The kid has changed the sequence of his game. He builds pyramids of snowballs and replenishes them to attack the tree. He doesn’t notice the approaching truck. The driver doesn’t pay attention to him. Or if the driver does, the kid doesn’t seem to matter. The driver doesn’t speed up, but he doesn’t try to decrease his speed. I manage to see the driver’s eyes: they are entirely black, as if his pupils had exploded and then spilled over his iris and sclera. The driver makes a turn at the corner and disappears north after running over the kid.

It takes me a couple of minutes to finish my cigarette. I extinguish it on the ashtray and go down to the street. The kid is just a stain of blood in the snow and fabric remnants. The kid’s body most likely got entangled with the truck’s chassis and will continue to be dragged until the truck reaches the north of El Barrio, the hideout of the corsairs. The kid is survived by half of his snowballs, his woolen hat, and his sunglasses. I don’t need the balls or the hat, but as long as the sun’s reflection off the snow persists in hurting my eyes, I will need some dark glasses. ![]()

Efraín Villanueva, a Colombian author based in Germany, has been the recipient of literary awards including the Barranquilla’s District Novel Prize (2017) for Tomacorrientes Inalámbricos, and the XIV National Short Story Book Prize UIS (2018) for Guía para buscar lo que no has perdido. His most recent book is the pandemic journal Adentro, todo. Afuera . . . nada (Mackandal, 2022).

Illustration: Sam Ward.