Let’s Call It Dissident | An Interview with Gabriela Wiener

Interviews

By Sylvia Georgina Estrada

Translated by Julia Sanches

At this point in her life, Gabriela Wiener (Lima, Peru, 1975) can no longer tell if she writes to live more or if she lives to write more. It was as a young woman, after studying literature and linguistics in college, that she realized, by writing, she could give voice to stories no one else was telling.

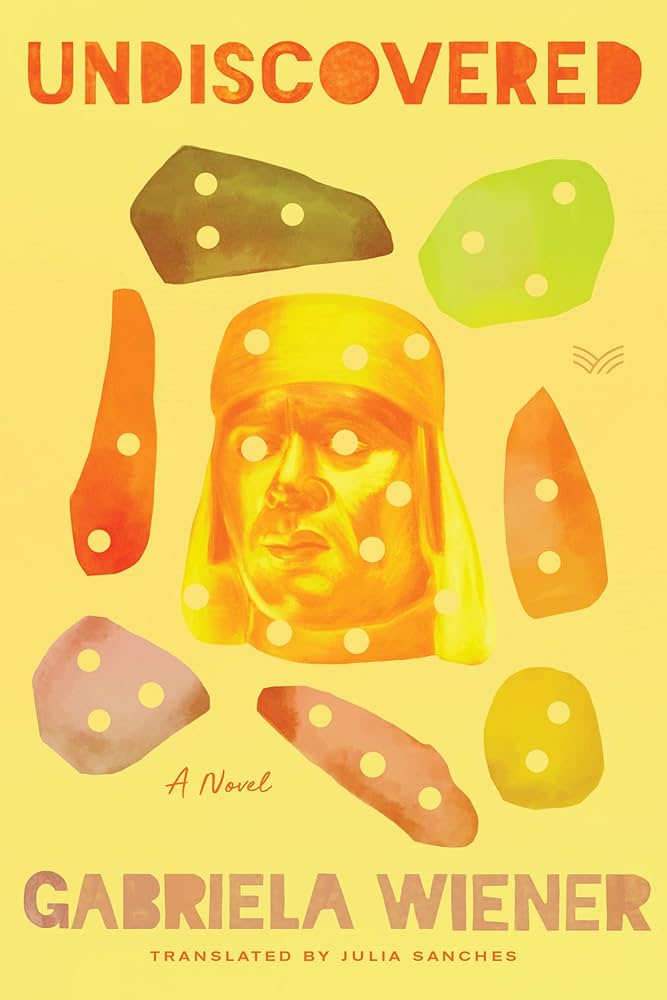

Her provocative, irreverent crónicas won her a prominent place in Latin American journalism. But her debut novel Huaco retrato (published in English as Undiscovered)—which follows the trail of her great-great-grandfather Charles Wiener, an Austrian explorer who absconded to Europe with thousands of archaeological objects obtained during his expeditions in Peru and other South American countries—hit the literary world with the cyclonic force that characterizes her work as an author. In fact, Undiscovered was longlisted for the 2024 International Booker Prize.

What are Gabriela’s obsessions? Her books contain stories about love, motherhood, desire, the exploration and appropriation of the body, and also racial violence, migration, and Indigenous communities. To Gabriela, writing is a form of resistance, and she doesn’t plan to cede an inch to the advance of ultraconservative right-wing forces and bien-pensant practices.

Sylvia Georgina Estrada: In the stories you tell, you’re just another character. You’re the kind of narrator who is personally, even intimately, involved in what they write. How did you choose your subjects in Sexographies, your book of crónicas about sex? What made you train your eye on these particular stories?

Gabriela Wiener: Narrative choices hinge on a person’s narrative personality. This has always been called style, but I think it’s more than that—it’s intuition. To me, most things are pure instinct: how we relate to the world, whether our worldview is lateral or “norm-centric,” where we’re looking, what we choose to see. Choosing to write about a specific issue has to do with which way our souls lean, where our eyes land. If I speak about people whose ways of life are twisted, it’s because my world, my way of being, is also twisted—or let’s call it dissident.

In my case, these narrative choices—what I write about, what I don’t, my angle—are connected to how I’ve constructed myself. The reason I write autobiographically is that all of this has been relevant to my point of view and to my story. I chose to tell a story about migrant bodies, dissident desire, and multiple loves not only out of desire but because of everything that has painfully conditioned me. Dissidence isn’t always a party; dissidence can also be exclusion. Racialization doesn’t necessarily look like “come to the museum to talk about our practices.” More often than not, racialization means being left out, discriminated against, bullied, et cetera.

We write with all the marks on us, our bodies, and make choices through these marks. This is how our worldview is conditioned, how our intuition is honed, how we move closer to empathy. Beneath every life is all this stuff that we have to move around and dredge up from depths hidden by taboo, especially in the kinds of stories in Sexographies, stories that have been silenced. Yes, Sexographies is a book that celebrates diversity, but it’s also a book that humanizes other facets of sexuality that have been trivialized or exoticized for a long time.

SGE: What has it meant to you to see Sexographies have such a long life, with new, expanded editions in Spanish and translations into other languages? The subjects covered in the book—the social construction of the female body, polygamy, sexual taboo, the economic precarity that pushes migrant women to sell their eggs (or rent out their uteruses)—are still present in the world even though you wrote the first crónica over fifteen years ago.

GW: Sexographies is definitely the book of my youth. My debut, it was published when I was thirty-two years old, already an old lady [laughter]. I remember I’d been writing for years by then, and I was seeing a lot of work coming out by these girls who were writing from a bitchy, slutty perspective, whereas I wanted to be more like Melissa P. or Catherine Millet. Books were being brought out by European women, obviously, and women from the United States, and Asia, but nothing from the south. Besides, deep down, I didn’t want to write that way. Time was passing and it dawned on me that I’d never get to be a literary sex icon [laughter].

After Sexographies, it became clear that I was the target of brutal racist bullying. People said things like “How can this woman possibly think she has the right to talk about her body, her desire? Who can even look at her?” It was a huge blow, but also a lesson: I needed to keep fashioning myself as someone who’s there, always reminding you that we’re resisting, that we’re putting up a fight, that we’re not interested in giving the system a nod—we are against the system.

SGE: Autobiography is a distinctive characteristic of your writing. Is there a kind of vital link between your books? Could it be said that Nine Moons, which delves into your own pregnancy and motherhood; Sexographies, which features a crónica about polyamory, something you practice in your romantic life; and Undiscovered, about your embarrassing colonialist ancestor, all make up different stages in the life of Gabriela Wiener?

GW: I don’t know if I write to live more or if I live to write more. Maybe life and writing have fused to the point where they’re almost indistinguishable. They nourish each other and exist in tandem. This, in a way, is transformative. Years later, as I was looking closely at the crónicas in Sexographies, I noticed that a lot of what has happened to me is connected in some way to the polygamy in the crónica “Guru & Family.” Or I think about how much my practice of feminism has been influenced by the travestis I met when I was very young, for the crónica “Trans.” Or how much my relationship with my partners, my lifestyle, my sexual freedom are all tied to the swingers’ club I describe in “Planet Swingers.” In fact, I don’t think they’re stories or accounts so much as my own rites of passage. These crónicas have changed my life. These things live with me and inside me. The stories in that book had a huge impact on me.

I feel like my work is a continuum, that you can find communicating vessels everywhere you look. Some people would tell me, “You’ve written about sex, motherhood, family, now it’s time to write about death.” Now that I think about it, there is a story about death in Llamada Perdida. The fact is, what I’m doing is building a body of work through the course of a life, my life. People close to me, people who are part of my migrant or racialized communities, can see themselves in Undiscovered. There’s a story being woven, one I started when I wrote my first book. They’re not independent stories; they’re being told in relation to what’s happening in the world. When my books are reissued, I get to ask myself: Is this dated, or is it still relevant, or do I still believe this? It’s an opportunity for me to rewrite, delete, or erase, but also to begin a new story, to say, “It’s time for a new book now.” I’m a writer of experiences, I always have been, but experience is also a product of imagination, invention.

SGE: Undiscovered is your foray into fiction. I wonder if you shifted your attention toward the novel form because there were gaps in your ancestors’ stories, in the story of your great-great-grandfather Charles Wiener.

GW: I introduced fiction into Undiscovered—something I’d never done consciously before—because I’ve written autofiction all my life. This book offers up imagination as an exit strategy for memories stolen by the West, by colonialism. Maybe we can fill in these collective holes left by the women who’ve disappeared—in the sense that they were made invisible—women whose stories have been denied. This is something that could also happen to us, to our own voices, if we don’t write our version of the story.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. Indigenous artists are always being referred to as artisans, and “real” artists hire them to procure materials or do manual labor. The upper, illustrious classes—with their marvelous studios where they paint, write, and do everything else—have an elitist view of art, they look down on everyone. There’s always some perfect label that gets slapped on the works of our great feminist artists, our queer artists, to devalue it and make it not be considered real art. It’s the same with literature. For years, while we’ve been producing literature, new terms have been invented to depreciate writing by women or dissident writing. First it was feminine writing, then it was feminist writing, now it’s activist writing—all to avoid calling it art. I want us to introduce an anticolonial, decolonizing perspective so that we can shed what is in the end, and always, the patriarchy of letters.

SGE: Now that your debut novel is out, have you considered writing a second one? Is there anything else you want to achieve with respect to these themes that are forged in the margins and that have to do with silenced voices, with resistance?

GW: I’m currently working on a new novel, a piece of satire. I want there to be a lot of humor in it because, honestly, I’m a riot, and I don’t take enough advantage of that. I tried to be funny in Undiscovered but just wound up being ironic. This time, I’m aiming for hilarious. So I’m writing a political comedy about a chola leader who wants to be president. She ends up in prison after these people find some stuff out about her and remove her from politics altogether. We’re going to see her past, her roots, where she’s from—she studied at an Indigenous Soviet school—and how she strayed from that path. Eventually, she finds her way back to her past. This is when she changes her name. She’s called Atusparia, after an ancestral Indigenous leader. I’m going to tell the story of how she tries to start a revolution and what happens internally when revolutions are attempted. The book is about all liberation movements. Why does this happen to the Left, to feminism? Why do we fall apart and out of sync? Why do we self-sabotage? These are the kinds of questions the novel is asking. At the same time, it’s a critical book where I get to tell all the funny stories I’ve got filed away.

Sylvia Georgina Estrada (Monterrey, Mexico) is a writer, cultural journalist, and publisher. She is the author of the books Músicas, La casa abierta: Conversaciones con 30 poetas, El libro del ldiós, and Pinacoteca del Ateneo Fuente: 100 años. Her work has been published in nationally distributed newspapers and journals, as well as anthologies of poetry, short fiction, and cultural journalism.

Gabriela Wiener is a Peruvian writer and journalist based in Madrid. Her books include Sexographies, Llamada perdida, Nine Moons, Dicen de mí, and Undiscovered, which was longlisted for the 2024 International Booker Prize, as well as the poetry collections Ejercicios para el endurecimiento del espíritu and Una pequeña fiesta llamada eternidad. In 2018, she won Peru’s National Journalism Award for her part in an investigative report on gender violence. She recently cofounded Sudakasa, a migrant and community art and writing project.

Julia Sanches is a literary translator working from Spanish, Portuguese, and Catalan. Recent translations include Boulder by Eva Baltasar, shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, and Undiscovered by Gabriela Wiener, longlisted for the same prize in 2024. Born in Brazil, she currently resides in the United States.

More Interviews