The Febrile Imagination of Andrés Neuman

Reviews

By Cory Oldweiler

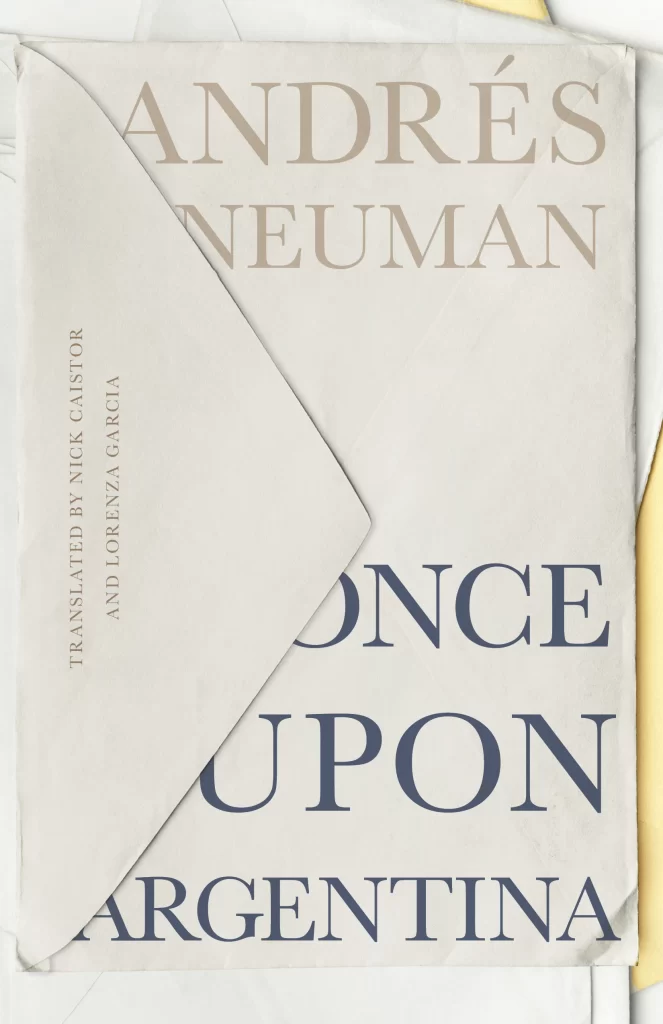

The Argentine-born writer Andrés Neuman once professed, “I don’t believe much in genres,” despite “supposedly working in all of them.” His remarkable output—nearly three dozen books over the past twenty-five years—does indeed come in all flavors, with roughly equal numbers of novels, short story collections, and works of nonfiction supplemented by twice as many volumes of poetry. And based on the subset of these titles translated into English, starting in 2012 with the masterful Traveler of the Century, Neuman’s apostasy toward genre convention is also readily apparent, a blithe disregard that continues with the newly released titles Sensitive Anatomy and Once Upon Argentina.

At first glance, the two books, both translated by Nick Caistor and Lorenza García (they also translated four prior Neuman titles, including Traveler), would seem to have little in common. The former is a slim volume blending whimsy, philosophy, physiognomy, and social critique, while the latter sits weightily at the confluence of fiction, autobiography, and history. But the books are thematically similar, investigating the parts that make up the whole: in the first case, the physical aspects of the human body that constitute the soul, and in the second, the people and historical events that created a kid named Andrés Neuman.

Sensitive Anatomy, originally published in Spanish as Anatomía Sensible in 2019, comprises thirty short meditations contemplating discrete aspects of the human body, all of which, save the final one, are facets of the flesh—the elbow, the neck, the eyelids, and so on. In the last chapter, Neuman links these physical attributes to the soul, definitionally the “immaterial essence” of life. The book has no specific narrator and exists almost outside of time and place, citing only a handful of cultural touchstones or historical figures. Despite this temporal vagary, the book still comments on societal forces that seek to dictate or judge our identity and behavior. It feels like the kind of thing Neuman worked on for fun in his free time, which is not meant to discount either its quality or substance but simply to acknowledge both his prolific output and febrile imagination.

The observations in Sensitive Anatomy are often witty (“For every verse penned about locks as golden as the sun, a hair throws itself into the abyss in protest”) or pithy (“The leg is half a couple, but also stands on its own”). And sometimes they are plain silly and empirically nonsensical, as with various assertions about eyes, such as “A black eye stays up late. The sky-blue one on the other hand enjoys breakfast and punctuality.”

These light-hearted moments leaven forceful pushback against prejudices. In the chapter about the belly, Neuman mentions the “measuring tape’s censorship” and satirizes the fact that “going out into the street with the appropriate belly is far more crucial for our elegance than any attire.” Body weight comes up again in the chapter on the buttocks, where he observes that “physical austerity is another imperialism; Capital grows fat on making us thin.” And racism is roasted in the chapter on skin, where Neuman mocks “the hegemony of the palest color, the least remarkable on the chromatic spectrum.”

Sexism is broached as well, as in the chapter on the foot: “Trapped between treasure and torture, the average female foot deals with its hurt in the name of an alleged beauty others impose.” While disdainful of gender roles, the book generally levels this criticism through binary arguments, though the chapter on the vagina does mention “a trans vagina,” stipulating that “those who dismiss it as artificial forget there is nothing more natural than the human will.” The discussion of the chest is a bit male-centric, as female breasts are parsed by shape—pointy, floppy, “the upward twist of the pastry cook breast”—and nursing is never mentioned.

Caistor and García capture the book’s punny chapter titles in “A Vagina of One’s Own” and “Penis without Qualities,” though any double meaning in others, like “Chest Luggage” or “Nose as Utopia,” escaped me. Their translation overall has several inspired moments, as with the metric precision of “Freckles are our condiment, a whiff of spices sprinkled on the skin.” In the chapter about the jaw, they retain the original wordplay of “mordida, mordisco y remordimiento” at the end of the sentence: “This explains why it is worth distinguishing between bite, tidbit, and bitterness.” (Though a case could certainly be made for a more apposite translation of “mordisco” as “nibble,” which retains the consonance but loses its stressed emphasis.)

The last chapter’s arguments for the corporeal characteristics of the soul rely on lexical ambiguity and linguistic double-dealing (“Any soul risks a sprain if it says yes when meaning no”), though occasionally these stretches are so strained they are spelled out, as with the assertion that the soul “appears just like the tongue (talkative, tasting, elusive).” The conclusion, however, leaves the reader convinced that Neuman might just be onto something: “The soul invents the soul, it doesn’t exist without the anatomy’s noises, it ascends a little further, shivers, laughs, and disappears.”

That lovely description could almost be an epigraph for Once Upon Argentina, a sprawling fictional autobiography that sees author Andrés Neuman invent narrator Andrés Neuman, who doesn’t exist without the voices of four generations of ancestors. The narrator tells his story up to the point in 1991 when he and his parents leave Buenos Aires for Granada, Spain, where the author resides to this day. Originally published in Spanish as Una vez Argentina in 2003, Neuman has revised the book twice, once in 2014, when he rewrote much of it, and again in 2021, when he made less-substantive changes. The first instance, Neuman says, was necessitated by learning “an overwhelming amount” of additional information about his family via further interviews and the burgeoning internet, information that ultimately came to occupy a mental “cajón del miedo,” or “drawer of fear,” that had to be emptied into the novel.

Andrés’s narrative progresses chronologically from birth to his family’s departure for Spain when he is fourteen years old, but it is broken up by arbitrary anecdotes from his ancestors’ lives. These relations, with roots in France and Eastern Europe, begin to arrive in Argentina—along with their passions and political tendencies—in the early 1900s. His Zionist great-grandfather Jonás flees the pogroms in Belarus. Another Jewish great-grandfather, Jacobo, in present-day Ukraine, steals the passport of a German soldier, which he uses to travel to Argentina with the new last name Neuman. His maternal grandmother Blanca, from the French side of the family, gives Andrés an autobiographical letter that inspires the novel he is writing.

The resulting jumble of stories adds momentum, breaking up purely expository passages that can be dry, but it also increases the possible disorientation of those not familiar with the vicissitudes of Argentina’s tumultuous politics in the latter half of the twentieth century, which included numerous coups, both successful and not. Neuman’s storytelling is at its best when family and history intersect, the highlight being the chapter when the narrator’s mother, Delia, is caught up in the 1973 Ezeiza massacre, where snipers attacked supporters of Juan Perón, who was returning from exile in Spain. A concert violinist, Delia is playing that day with one of the two orchestras “squashed together like musical mercury” that are accompanying the festivities, and throughout the chapter, Neuman emphasizes the music of her memory. Delia smells “some chord made up of macerated grass, warm wood, bow rosin, damp air, collective sweat, [and] distant meat being roasted all day at the nearby camp sites.” When the snipers begin shooting, the whole scene is “shattered by the chaotic rhythm of bullets and screams,” screams that soon “formed a vast choir out of tune, the music of terror.”

For the next decade, Argentina’s government carries out a systemic effort to kill or “disappear” thousands of left-leaning opponents. Soon after the military takeover in 1976, the narrator’s great-aunt and great-uncle flee to Brazil after answering their phone and hearing a “friendly voice” say nothing but “Get out.” Another aunt and uncle, Silvia and Peter, get no such warning. They are accused of being rebels, lose their business, and then get kidnapped. Silvia is tortured while Peter is made to watch, but through a political favor the couple is released, whereupon they become the first Neumans to return to Europe, fourteen years before Andrés’s family would follow them.

The cast of Once Upon Argentina also includes “a handful of casual beings who complete our family picture,” one of whom is Franca, a student of the narrator’s father who is the subject of only a single paragraph but nevertheless becomes one of the book’s most memorable figures. Franca disappears when she is “sweet sixteen,” but no one knows why, leading the narrator to insist that “she had to be somewhere: people don’t cease to exist from one day to the next without leaving any trace. Do they?” The implication is that Franca is either a victim of femicide, the endemic killing of girls and young women throughout Argentina, or simply another tragically young victim of the governmental vendetta.

Caistor and García again manage some impressive bits of wordplay, as in a passage about the student roll call at school as it ticks through the alphabet toward the name of the narrator’s classmate Santos, “and the same letter that summons the silent, solitary, stolid, suffering, submissive, or smart dragged Santos toward the principal’s desk.” They also retain words like the Yiddish zeide, for grandfather, and the cracker brand Criollitas, which keep the reader firmly ensconced in the narrator’s transplanted Argentine family. This grounding is lamentably offset by the decision to refer to the sport that everyone outside of the United States calls football as soccer. It’s an immediately distracting word choice given its inextricable Americanness, and is made even more confusing by continuing to refer to the ball itself as a football.

For his part, Andrés the narrator learns about class differences from the family’s maids, who hail from the north of the country, where there is rampant poverty and no work. He wrestles with the notion of manliness that is foisted on Argentine boys at a young age, even while describing his pornography collection, which he stores in a puzzle box. And inspired by authors like Edgar Allan Poe, he starts writing adolescent short stories that incorporate horror-inflected themes that continue to be prevalent in contemporary Argentine fiction, though Neuman has never really embraced them in his fiction that has been translated into English.

Like many memorable motifs, the theme of music is reprised near the end of Once Upon Argentina, revealing itself to be the animating force in the narrator’s life. “In my memory there’s a musical score. From before I was born, on the threshold of the belly of this world, I listened to music.” The chapter goes on to describe the prevalence of music in Andrés’s childhood, which came not only from his mother’s profession and passion, but also from his father, who gives lessons and plays the oboe. Neuman’s mother died after the book’s original publication, and during the 2013 rewrite, he dedicated the book to her. I have no idea how this chapter was changed during that time, but it closes with the narrator’s emotional farewell to his mother, telling her that “in the silences, I hear you breathing.”

Music is an apt analogy for a book underscoring the events and people that constitute our lives, much the way individual notes, voices, instruments, and silences combine to make a tune, or “anatomy’s noises” enable the soul. Music is referenced several times in Sensitive Anatomy as well, most memorably in the chapter about hands: “Apart from the vocal kind, all music is made by them. This is why our finely tuned Spanish speaks of touching music, whereas others say playing.” The astute observation, which may be missed by those unaware that the Spanish verb tocar means both to touch something and to play an instrument, highlights perhaps the most unique quality of music, its universality. Music can shape a life or gratify your soul, wherever you may be born or disappear to.

Cory Oldweiler is an itinerant writer who focuses on literature in translation. In 2022, he served on the long-list committee for the National Book Critics Circle’s inaugural Barrios Book in Translation Prize. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe, Star Tribune, Los Angeles Review of Books, Washington Post, and other publications.

More Reviews