No Good Nights | Brian Evenson’s Good Night, Sleep Tight

Day after Labor Day, I got a call from my dad back in Arkansas. Mom’s sick, she’s fallen, she’s in a rehab hospital for fourteen days. Implicit was the question: “Can you come?” I made arrangements for my classes and drove twelve hours from Georgia. I hadn’t been home in almost two years.

On the way, I drove through the east Arkansas Delta town where I’d spent a few years of my childhood. We left there when I was seven, but I have strong memories of that place. First memories. The white-columned house we rented at the edge of a sprawling field of Johnson grass. Pine trees. My first puppy. Friends made at school, a He-Man birthday party. Christmases with snow. A brick, too, thrown through a picture window late one night. (They never caught the guy, but Dad had his suspicions. He’d suspended an eleventh grader from school that week who kept a black notebook full of names; some of the names had checks by them, lines drawn through them. Dad’s name was in it. No line. No check.)

The house was gone. Burned to the ground. A heap of soot-black rubble overgrown with dog fennel and kudzu. Not even a chimney left standing.

At first, I couldn’t believe it. Was I looking at the wrong place? But I remembered the driveway, the dilapidated garden shed. The little bald patch of ground where a dog pen once stood. And the ruin of the house trailer across the street, where an odd, excitable woman named Pat had sat our cocker spaniel when Mom and Dad were at work. Pat loved dogs.

I circled the block. Drove on.

![]()

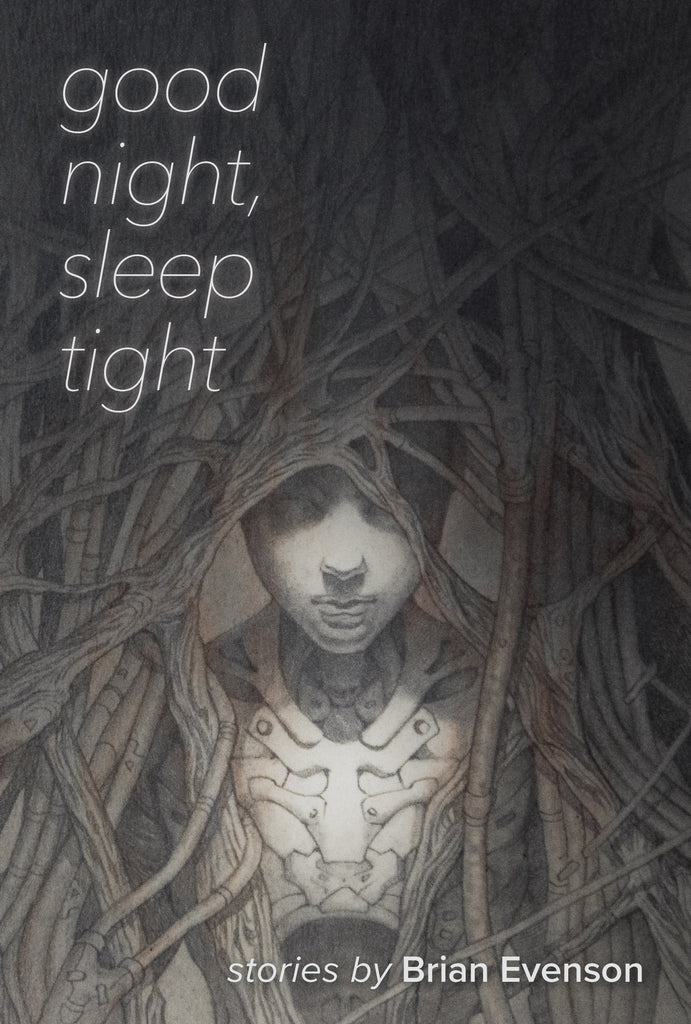

I always take one book to read on any trip, usually a horror novel. I’ve written three of them myself and can’t seem to quit the genre. It speaks to me, comforts me from the existential dread of daily living. The book I took to Arkansas was Brian Evenson’s Good Night, Sleep Tight. I’d read about half of it by the time I checked into my hometown’s only functioning hotel. Enough to know it’s a book about childhood, about dreamtime ghosts conjured out of the dark by words and ritual. Like almost all of Brian Evenson’s collections, it’s a gathering of stories that worries at a theme, pulls at some cosmic thread you’d just as soon stay un-pulled.

Its protagonists are children, robots, travelers. Innocents, mostly, who encounter impossible moral dilemmas in the cold, far reaches of snowy woods or starry space. It’s a book about how words mean more than what we think they mean, how stories can be traps laid by devils collecting souls. It’s about home, how it’s inevitably a place of violation. Of trespass. No safe space, your childhood bedroom. In this, the title becomes ironic: there are no good nights, and the tightest sleep is one from which we do not wake. Take the robot protagonist of “Mother,” one of two brothers who gradually discovers the horrible (and inevitable) nature of his birthright. “We had lived in that place for years,” he says, “before I came to understand that all was not as I believed it to be.”

He’s talking about home, yeah?

![]()

Characters in Evenson’s book often wake at night alone. They wake alone and know they are not alone, some malevolent presence among them. They know they cannot afford to be alone, and so they shuttle down their childhood hallways for their parents’ bedrooms, desperate to escape whatever dark things lurk in that liminal country between sleep and waking. That space where the veil between childhood and adulthood is thinnest.

By day, I shuttled back and forth from my parents’ house in south Arkansas to the rehab hospital in Texarkana. Most of us with aging parents know how these things go, but there can be surprises along the way. Maybe you grow a bit closer to your dad over Whataburgers and conversations about old high school friends on Facebook, where they are now. Who got fat, who lost hair. Whose kid started college. Whose kid died. Maybe, too, you see a side of your mom you knew was there but had forgotten since childhood: her grit, her strength. The way she used to grip the fish you caught and yank them from the hook, careless of those sharp fins.

By night, back at the hotel, I cracked Evenson’s stories, and they pulled me into a world that seemed, somehow, reflective of all the demons I was wrestling with: the waking pull of adulthood, the dreaming state of childhood. How parents make you, beget you. And somewhere along the way, just maybe, they betray you. In Evenson’s book, they feed you to monsters. Or eat you themselves.

![]()

In “Good Night, Sleep Tight,” a mother refuses to admit she ever told her son scary stories in the dark, and when the truth is finally revealed, it’s even more horrifying than if she had. Turns out, her doppelgänger slipped out of shadows night after night and whispered dark, awful tales. A thing masquerading as a mother. Imagine it.

One night I couldn’t sleep. I got in the car and drove around my hometown, saw it from that weird, 3:00 a.m. arc-sodium perspective. I drove out to the little rural community where I’d lived, a crossroads with a church and a school. Dad had been principal of that school, and later superintendent, for the bulk of his career. My childhood home was a boxy little house across the street—free housing, provided by the school. A perk of Dad’s job. The night we moved in, summer of 1986, we sat on the little screened-in porch and watched heat lightning flash off beyond the rooftops of the high school, the water tower. We were each of us pilgrims come to a foreign land. We were a family.

Now, the street and school grounds were shadowed and quiet. I rolled up to the intersection and looked out at the place where I had spent my childhood. It was razed. A FEMA-style trailer planted there on a manicured lawn. Home to a Head Start program, maybe, or a reading lab.

Once upon a time, there were Batman posters on the walls. Bins of action figures in a closet forever cluttered. Shelves lined with books. Nintendo games played on a thirteen-inch Montgomery Ward television. A cedar chest at the foot of my bed, draped in an afghan my grandmother knitted. My memories of this place. This empty lot. This deleted space.

I felt like a ghost, come to haunt it.

![]()

“There are times when it hurts to be alive.” So says the narrator of the shortest story in Evenson’s collection, “A True Friend.” It’s a piece about helplessness, what it feels like to be ignored, to be caught up in the grip of someone else’s icy lack of mercy. To watch another’s pain with a cold, satisfied contempt. To relish, even, that pain.

There are times, I suppose, we all might say: I don’t understand my parents. Maybe we don’t understand their choices, why they choose the roads they travel. Maybe we don’t understand their miseries because they are, to some degree, self-inflicted. Violations of the rules they taught us to live by: Eat well. Pray. Go to the doctor. Brush your teeth. Be wise with money. Treat others the way you want to be treated. They shock us, as they age, breaking long-established character. Becoming, in a sense, almost childlike in their refusal to follow their own good advice.

And yes, there are, I suppose, times when it just hurts to be alive. When all the problems of the world seem to hang upon your father’s shoulders, and you find yourself staring at him picking at the leftovers of a patty melt and thinking, I love you, but I can’t reach you. Or you watch your mother learn to walk again, watch her circle words in a word search book and wonder at the mystery of that woman who once slapped your mouth when the word “Fuck!” flew out of it in anger.

My favorite characters in Good Night, Sleep Tight are Evenson’s robots. They exist outside of the expected norms of human interaction; they learn how to be by comparing what knowledge they were given at birth to the contradictory actions of those around them. Inevitably, in this book, the people they learn from are their own parents. Or other children. They learn about words, how they bend and flex “in individual mouths to become something else, a sort of private code.” In my favorite of the stories, “Imagine a Forest,” a robot literally becomes its own mother, as her memories are downloaded into its brain aboard a spaceship containing the last survivors of a doomed Earth. The ship, too, is doomed, the sleep pods compromised. The robot can save only nine humans—nine from hundreds of scientists, engineers, philosophers, etc. The robot, shaped by the fables its mother told it, chooses to save the children it grew up with on the ship. Or most of them. The story is complex beyond all others in the collection. It gets at how parents wield their godlike power in service of others and themselves, yet they’re as human, as flawed, as the children they mold. In fact, when it comes to being human in this book, no one, not even the robots, achieves escape velocity.

We were finishing our burgers one night and I asked Dad if he remembered Pat, who used to keep our cocker spaniel way out in east Arkansas. He cocked his head, meaning he hadn’t heard me. I said it again, fewer words. Louder. He nodded. I told him a story, a memory from childhood. How she’d seen a snake in the ditch one day at the end of our driveway and peed herself right there in the road. Spread her arms wide, flapped them like wings, and ran a stream of piss right down her leg where it puddled on the asphalt. “I’ve never seen anything like that since,” I said.

“She still lives in that trailer,” he said. “I messaged her on Facebook a while back, told her your mom and I would like to come see her.” He paused. Turned a French fry in ketchup. His hands shook. “She told us she didn’t want anyone to come see her. She said, ‘I live here with my dogs and I would be ashamed for anyone to see how I live.’” Dad looked up at me. “‘I’m waiting to die,’ she said. Can you believe that?”

I didn’t know what to say, but yeah, I could believe it. That’s the thing about horror stories. They ring the truest for reasons we don’t like to say aloud. I thought of my parents’ own house, bought when I was a junior in high school. I’d lived there only a few short years, summers in college. Long enough to get attached—weekends fishing the lake from the front yard, burning pine straw at the edge of the treeline, that warm, autumn smell of smoke. Whole days spent reading Stephen King novels in a front porch rocking chair. But it was just a house, with old pipes and old wiring. Too far from anywhere when Mom fell. I thought of the rooms in the hospital where Mom at that moment lay sleeping, wide doors opening onto bereft souls robbed of dignity, privacy. Their mouths open as they snored in their railed beds. Most in diapers. Beeping machines and the odd moan out of a darkened room.

I thought of Pat. Alone in her trailer. Peering out the window at some car moving slowly past, its driver staring for the longest time up the narrow driveway across the road. Who is that? Why is he here? Some tiny dog clutched at her breast, trembling in her arms.

![]()

In “The Night Archer,” a sister tells her brother a bedtime story to distract him from their dying mother. A fable of a sinister huntsman with a bow of yellow bone, arrows tipped with bits of jagged mirror glass. Summoned by tapping a coin against the fireplace mantle, the archer’s task is to kill whomever the summoner wishes. Stories, again, imbued with power. Whipped up by tellers in broken, ruined homes with absent fathers. The boy, of course, summons the archer. His ultimate request: “Make my father your prey.”

Dad wants to sell the house. Find somewhere better—safer—to live. Closer to people, to hospitals. I’m all for it. I spent a whole day at the house screwing in grab bars to wall studs in the shower, rearranging furniture to accommodate a walker. On a Tuesday, after seven days there, I drove Mom home from the hospital, while Dad went grocery shopping. Together, she and I rehearsed the best way to navigate the narrow hallway. Relearning how to sit and stand and move in a too-small bathroom we had always taken for granted.

I got home to Georgia the next day. I’m ashamed to say I drove like a man trying to achieve what none of Evenson’s characters manage in Good Night, Sleep Tight—that escape velocity. Crystal and I live on about sixteen acres across from a cotton field. Sometimes, it feels like we’ve done just what those homeless earthlings in “Imagine a Forest” have done: we’ve found ourselves a new planet, uncorrupted. We’ve started over, here among the red-shouldered hawks and deer and rabbits. There’s a patio out back where I like to sit beneath shaded trees and watch frogs hop in and out of our little brick pond. Frogtopia, we call it. This is my forever home, no childhood homes left. I sometimes think I could die sitting right there on that patio, an old man beneath autumn leaves falling, and that would be fine. I’m grateful for that thought. Because it means I haven’t made the wrong choice. I haven’t taken a wrong turn like a character in Evenson’s collection. I haven’t made any unholy pacts that I’m aware of to buy such happiness. I haven’t summoned any Night Archers to hunt my enemies, or my loved ones. I try to live like the child my parents raised, to keep alive that ghost of a boy they imagined me to be. Be a good man, do the right thing. Avoid the shadows in the periphery when they bleed through from other worlds.

But these are daytime thoughts. In the night, when the clock is ticking and the lights are out, and there is only the dark pressing in beyond the windows, and the wind is in the pines out back, sometimes, yes, the shadows move. Figures appear out of walls, darting phantoms at the edges of my vision. The child inside rears up and longs for some hallway to thunder down, some adult bedroom to burst into and crawl beneath the covers. But there is only my hallway now, my bed. And I am not so armed against these monsters anymore. If I ever was. We get old. We cling to the hope the stories are not traps. That they’ll save us. But for me, they’re horror stories. Always. Good night? Sleep tight? Good luck with that.

Andy Davidson is the Bram Stoker Award-nominated author of In the Valley of the Sun, The Boatman’s Daughter, and The Hollow Kind. His novels have been listed among NPR’s Best Books, the New York Public Library’s Best Adult Books of the Year, and Esquire’s Best Horror of the Year. His short stories have appeared online and in print journals, as well as numerous anthologies, among them Ellen Datlow’s Best Horror of the Year. Born and raised in Arkansas, Andy makes his home in Georgia, where he teaches creative writing at Middle Georgia State University. He lives with his partner, Crystal, and a bunch of cats.

More Reviews