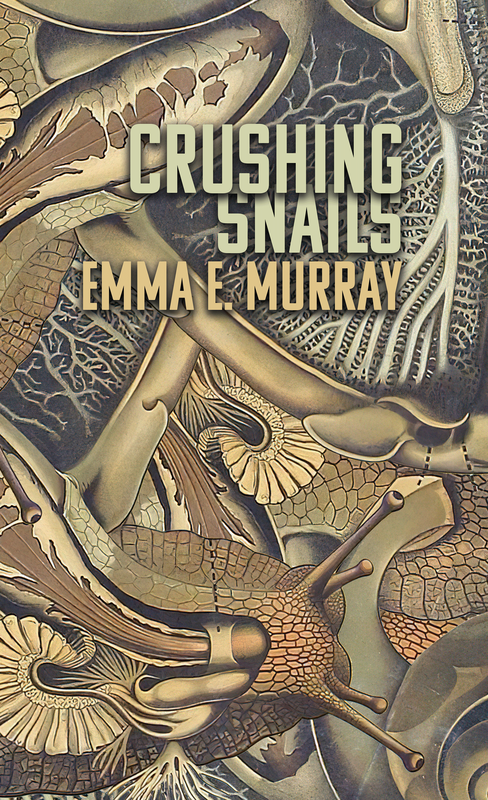

Total Disgust Achieved | Emma E. Murray’s Crushing Snails

The purpose of art is to make us feel. Sometimes we feel beauty and awe. Other times we feel terror and disgust. Both reactions are powerful, and they take us somewhere deeper, a stranger place we never knew existed. Emma E. Murray’s debut novel Crushing Snails follows the brutal, unsettling journey of Winnie Campbell, a teenage girl turned serial killer. The narrative alternates between police interrogation transcripts involving Winnie’s inner circle and her own dated entries, covering the days leading up to her disappearance. These intertwined storylines reveal the mystery of her vanishing and the terrible circumstances surrounding it, ultimately arriving at a blood-chilling conclusion.

During the final weeks approaching Winnie’s disappearance, we accompany her down a tenebrous path that rapidly spirals. It’s a journey fueled by a frustrating lack of power in all aspects of her life: family, friends, love interests—even her time, energy, and physical body are not within her control. We suffer alongside her through the thankless role of family housekeeper; despite her best efforts, it’s almost never good enough for her father Cole, who wrongfully blames and resents Winnie for her mother’s death. The unusually vicious discipline he doles out to Winnie is sometimes provoked by her bratty younger sister, Lilly, who will do anything to get her way, and mostly ignored by her brother Brendan, who also has his own demands for Winnie. We observe the ambivalent friendships with her friend Gabe, who appears to be almost as condescending and arrogant as he is supportive, and Krystal, who has naturally grown apart from Winnie since she moved away, attending a different school and developing different interests. We experience short-lived hope that quickly turns into disappointment and heartache from both of Winnie’s potential romantic interests.

The novel wastes no time exploring this multifaceted brutality. It opens with a vivid and unblinking snapshot of the tragic night when eleven-year-old Winnie is physically and emotionally scarred, left alone to sink into despair. Eleven-year-old Winnie begs her mother Theresa to stop drilling holes in the middle of the night, a task fueled by paranoia and conspiracy. After Winnie is reduced to tears because of exhaustion, her mother seems to sympathize with Winnie, offering her tea and a snack as consolation. When the teakettle whistles, Theresa throws the boiling water onto Winnie, burning her face and body. Then, as Winnie weeps, Theresa pours hot oil from a pan onto Winnie’s face. Winnie’s only hope is her father, who instead concerns himself with Theresa’s well-being and demands that Winnie lie to the cops. Winnie is left alone in the back of an ambulance.

The language crackles with a hideous cruelty: “I hear it sizzle as I claw at my damaged face and arm, trying to wipe it away, but it’s no use. The pain jumps through my brain like a white-hot flash. I try to squeeze my eyes shut, but as I thrash, the oil runs into one and I howl. My hand reflexively grabs at my face and the skin sloughs off from my cheek in a sticky sheet. The sensation of thick liquid oozing out of my injured eye, streaking warmly down the scalded flesh, causes terror to pulse through my being. I vomit down my shirt.”

In this scene, we experience a range of conflicting, visceral emotions. We are sympathetic to her mother’s unwellness until we are angered by it, shocked by the unthinkable act of throwing boiling water and hot oil onto a child. We settle into heartbreak and defeat alongside Winnie when her father abandons her for her assailant. We establish strong sympathy for this innocent child, undeserving of such sadism: “I lay forgotten on the kitchen floor. No, worse than forgotten. I am trash. Lower than trash. The way they look at me and then each other, I wish I would die already.” This opening acts as a litmus test for readers. Although it’s a fraction of what lies ahead, the story forces the reader to either commit to the journey or get out while they have the chance.

This ceaseless rhythm of disheartenment, indignation, and sadness propels a desperate, teenage Winnie to attempt any means of release, relief, and control through the only method she knows: exercising absolute power over the defenseless. She starts with the titular act of crushing snails as she walks through the woods—one of the only places she isn’t subjected to the will of others—and it’s here that we see the first glimpse of true happiness for Winnie: “I smile wider. Almost laugh. A wild heat rises through my body.” And later, “I never knew destruction would be so enjoyable. Maybe if I’d known, I’d have started long ago.” Once she feels the thrill of destruction, she can’t stop; soon, she craves bigger, more challenging victims to satisfy her desire for power and control. Crushed snails mark the beginning of the end.

Because we live in an era inundated with sensationalized violence and true crime media, especially stories of serial killers, it is tempting to dismiss labels or content warnings as mere formalities. We can also anticipate some of the triggers within this story—bullying, child and animal abuse, torture, and murder of innocents. Readers mustn’t let their guard down with Crushing Snails, though. It is rightfully labeled extreme horror and demands serious attention. This novel is not for the squeamish or fainthearted.

This “extreme” distinction is made for the genre because, although most horror consists of similar subject matter and imagery, the average horror novel often merely flirts with atrocity, setting up the violence to come and letting readers fill in the details for themselves. It also tends to respect some boundaries, like avoiding depictions of harming children or animals. We might see the ax-wielding maniac raise his arm, but the scene cuts to the sorority girl lying in a pool of blood—the murder is implied.

The subgenre of extreme horror aims to elicit visceral reactions of terror, disgust, and trauma. Nothing is off-limits, and it embraces the graphic and gory. There is no rushing through the violence, no fade-to-black for relief. We witness the knife enter the body with force, we hear skin torn open and the intestines ooze out, we feel the blade gliding through the torso: total disgust achieved.

Crushing Snails stays true to the extreme horror genre, sparing no gory detail or tender feeling. Where others may hesitate to even suggest, the novel confronts head-on, forcing us to bear witness to atrocities that would make even a hardened reader flinch: the humiliating, physical punishment from Winnie’s father that evolves into sadistic torture with clothespins, hot wax, and physical restraints; the poisoning of a neighbor’s dog and its dissection with surgical precision for fun; a dangerous game involving a newborn gone too far.

But Murray isn’t satisfied with cheap thrills, so we aren’t mere witnesses in this story. Witnessing, however brutal, is passive and two-dimensional. In order to leave a real mark, or a stain, or a scar, the story must demand that we endure the violence and participate in these disturbing acts ourselves. Crushing Snails often employs the first person, fully immersing the reader in the story through Winnie’s eyes. Through Winnie’s perspective, the unyielding gore and tragedy evokes a pulsing, visceral effect—simultaneously stomach-churning and heartbreaking—both in the psyche and in the physical realm. This book makes us hurt.

It goes without saying that this book will captivate horror fans. Its ability to cut deep and stare into the wound is impressive. Though I am an avid horror enthusiast, it isn’t the graphic violence and unfathomable depravity in Crushing Snails that kept me reading. I’m interested in the complete spectrum of human possibility—from the saints to the serial killers—because there is just as much knowledge to be gained from the darkness as there is from the light, even if at first we can’t make out what it is. We must let our eyes adjust and observe. It is this courage to explore what lurks in the shadows that gives the book its power. When Winnie makes her final, shocking kill, she feels like she has become “something different altogether. Nameless, powerful, and finally almost free.” In the jet-black aftermath of murder, there is a glimmer of relief, even hope. We see the possibility of a new life for Winnie, though it has come at an unfathomable cost.

Crushing Snails offers a look at the underbelly of humanity, and the book’s strength lies in its ability to make us feel something—even if the feeling is awful. The psychological complexity of Winnie and her story challenges our supposed boundaries and asks how far we’re willing to descend into the moral gray area. We might be repulsed by what we see. But we will also be moved. It might even break our hearts.

Brandi Gaspard is a devoted reader and writer. Born in Alabama and raised in Jacksonville, Florida, she lives in New York and is currently studying thanatology at Brooklyn College.

More Reviews