Metafiction, Magical Realism, & Mourning

Reviews

By Adrian Van Young

Disappearance is as common in magical realism as earthbound convention is uncommon. In Gabriel García Márquez’s 1967 novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, the progenitor of magical realism as we know it today, the character of Remedios, aka Remedios the Beauty, the daughter of Arcadio and Santa Sofia de la Piedad (lower limbs on the Buendía family tree), is hanging out laundry one day in the garden when, suddenly, she floats away. It’s one of the most delightful, funny, and obscurely sorrowful moments in a novel that offers no shortage of the same, and like so many of the otherworldly miracles that leap from the pages of García Márquez’s masterpiece, there’s little explanation for it. Later, it’s suggested that Remedios the Beauty’s disappearance was due to her being too lovely, innocent, and wise for this world, a logic chaste in its illogic, which arguably furnishes magical realism as a genre its power. García Márquez isn’t just being glib: Remedios never returns to this earth. Her ascension marks a sudden, melancholy disappearance in a novel replete with scores of others.

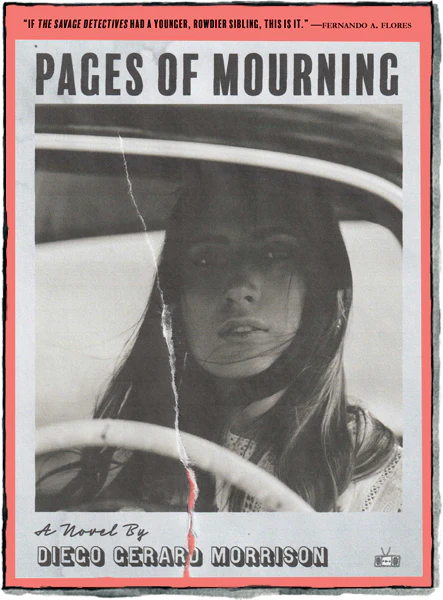

Although Diego Gerard Morrison’s newest novel centers on a disappearance ultimately as permanent as Remedios the Beauty’s, overtly magical episodes such as García Márquez’s are scarce in Pages of Mourning (Two Dollar Radio). By and large, that’s by design. Mourning’s antihero, Aureliano, named by his parents after the fictional patriarch and protagonist Colonel Aureliano Buendía from One Hundred Years, is in the midst of writing a metafictional novel that, in the protagonist’s own words, “sets out to discredit Magical Realism as a genre”—at least when we find him at the beginning of the book. “The idea is to situate Magical Realism within the literary canon it belongs to,” Aureliano goes on to say, “as opposed to being a pseudo-canon of its own.” According to Aureliano, that canon is “fantasy,” as opposed to “reality,” or realism, in which Aureliano, somewhat foolhardily, places himself.

To make headway in his project, Aureliano is on a writing fellowship in Mexico City by way of New York, having been thrown a nepotic bone by his aunt Rose, a celebrated author in her own right and Aureliano’s host and sponsor in the capital city. In the opening chapters of Mourning, Gerard Morrison portrays the city with arresting sensory richness, its “endless taco stands stationed under plastic tarps” with their “untold rations of shredded pork sizzling on hotplates,” against the backdrop of music that “cross-fades between narco-corridos, cumbias, and pop blown in from the world’s real capitals.” But Aureliano’s time in Mexico City is more than just tacos and jammers: Aureliano, haunted by the ghost of his dead buddy Chris (giving off distinct guy-in-your-MFA-program vibes), has a pretty serious drinking problem; the literary scene is infested with gatekeeping hipsters; and the parents of forty-three forcibly “disappeared” students, presumed murdered by the government three years prior, are marching on the city to demand their return, or an honest confession.

Here is where the influence of another important and distinctly Mexican practitioner of magical realism begins to assert himself in the plot of Pages of Mourning—namely, Juan Rulfo, author of Pedro Páramo (which actually predates One Hundred Years by over a decade and was as large an influence on García Márquez as it presumably was on Gerard Morrison). In Rulfo’s novel, a man seeking to fulfill the promise of seeing his absentee father into the next life arrives in Comala to find a literal ghost town awaiting him, populated by a chatty and shifting array of shades and mortals. Rulfo, just like García Márquez and now Gerard Morrison, was a writer obsessed with legacies of political and interfamilial violence, as well as the unreckoned absences left in its wake. In regard to his country’s prolific and abnormal relationship to death and erasure, Rulfo once famously said, “In Mexico, nobody ever dies. We never let the dead die.”

Mourning’s Aureliano embodies a similar paradox. Aureliano knew his mother before he could walk, but sadly hasn’t seen her since. Aureliano’s father, Lázaro, lives in the real-life Mexican town of Comala. In addition to name-dropping Rulfo and his work frequently while sipping mezcal with Mexico’s literati, Aureliano himself, as a part of his Under the Volcano (no joke!) fellowship, is composing what he considers to be a failed novelistic portrayal—a lengthy metafictional segue in the actual text of Mourning called “Snake Skin: Brief Passages in the Life of Édipa Más”—of his mother’s young adulthood as a disaffected weed-farmer on the run with Lázaro from Mexico’s then-burgeoning drug cartels in the ’70s. In that book—which, remember, seeks to “discredit Magical Realism as a genre”—Aureliano’s mother, Evelina (who renames herself Édipa Más in self-conscious homage to Thomas Pynchon’s 1966 novella, The Crying of Lot 49), embarks upon her own enigmatic disappearance during Aureliano’s infancy. This narrative is retold yet again toward the end of the book from the perspective of Lázaro, in an extended, Roberto Bolaño-esque first-person monologue.

If this webwork of literary allusion and nesting-doll narratives sounds overdetermined that’s because it is—somewhat. Gerard Morrison manages to launch a whole lot of balls in the air without ever precisely illuminating his point on either the vitality or the insufficiency of magical realism. Although, admittedly, Gerard Morrison at least is able to pose questions about the genre with more fluency than one might expect of such an operatic confluence of postmodern techniques—not to mention the fact that the metafictional novel-within-a-novel of Aureliano’s mother’s youth spent running from the cartels contains word for word some of Mourning’s best and most compelling writing. Take, for instance, the following painterly passage describing Doña Meme, a storeowner in the Tomatlán-adjacent town where Aureliano’s parents cultivate their sativa under rows of coffee plants, feeding the blackbirds that roost in the branches of a tree: “She walked barefoot over the sun-stricken dust . . . tossing a flurry of seeds right outside the store, in the shade of a tall Jatropha tree that housed countless birds, all of them hidden by bushy leaves yet vociferating a unified chirp, melodious, the avian version of the harmony of voices at Capri. One by one they flew down, tiny blackbirds over a litter of seeds, feathered wings dazzling in the sunlit gaps between the shade.”

Just like Pedro Páramo, Mourning is narrated along a nonlinear timeline, and just like so much of Thomas Pynchon, the novel is fraught with winking, narratorial trapdoors, deadfalls and double-backs that crowd around the disappearance of Aureliano’s mother. It’s a devastating personal loss for Aureliano that is cleverly magnified into a devastating national loss for Mexico, calling to mind not only the forty-three missing students and Rulfo’s undying dead, but also the untold number of Mexican citizens “disappeared” over the course of the last century through political violence, the wages of the drug war, deadly border crossings, femicide, and earthquakes. Aureliano circles, too—first, back to Rulfo’s Comala, where he works as a coffee picker on his father’s ranch and sits for an amusing, tequila-fueled recapitulation of the real-life events that comprise his own failed novel; then, after the inevitable revocation of his writing fellowship, on to New York City, where he attempts to resist Rulfo’s pronouncement, and at last “bury [his] dead” in the form of his guy-in-your-MFA-program buddy, Chris.

In the final quarter of the novel, inexorably, Aureliano is drawn back to Mexico to reckon with an unexpected family tragedy in a way that seemingly reasserts magical realism’s primacy as a playful literary instrument for indexing and understanding staggering injustice and loss. And yet, unlike so much of Rulfo or García Márquez or, for that matter, Salvador Plasencia (whose 2005 novel The People of Paper is perhaps Pages of Mourning’s most direct antecedent), the novel’s last third is so crushingly earnest that, in many ways, it undercuts its own objective. Rulfo and García Márquez didn’t play, but at least they were able to laugh at themselves. Pages of Mourning, finally, then, is a bookish, ambitious, and strangely compelling novel that in some part falls prey to its own aesthetic project. In attempting to reckon with the recursive absences and disappearances that spot its pages, the novel finds itself among them, neither living nor dead, an outline shaded vaguely.

Adrian Van Young is the author of three books of fiction: the story collection, The Man Who Noticed Everything (Black Lawrence Press), the novel, Shadows in Summerland (Open Road Media), and the collection, Midnight Self (Black Lawrence Press). His fiction, non-fiction, and criticism have been published or are forthcoming in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, Black Warrior Review, Conjunctions, Guernica, Slate, BOMB, Granta, McSweeney’s and The New Yorker online, among others.

More Reviews