A Bonkers Artist Heart | Emmalea Russo’s Vivienne

Reviews

Once a year at my Catholic elementary school, all the second, third, and fourth graders would head down to the school chapel, where we’d sit in the pews in alphabetical order and wait for our turn to confess our sins. It was easy to tell when you were up next, because our chapel didn’t have confessional booths. Instead, two priests sat in folding chairs on either side of the altar. Two by two, we’d head up to the front of the room, sit next to a man we’d never met, look out at a crowd of our peers, and whisper our most shameful secrets, hoping our voices didn’t carry. Our religion teacher told us that the priest was just a conduit for God’s mercy, but it felt like you were sitting up there with a judge, while a whole courtroom of second graders stared back at you. Your sins were between you, God, and everyone you knew.

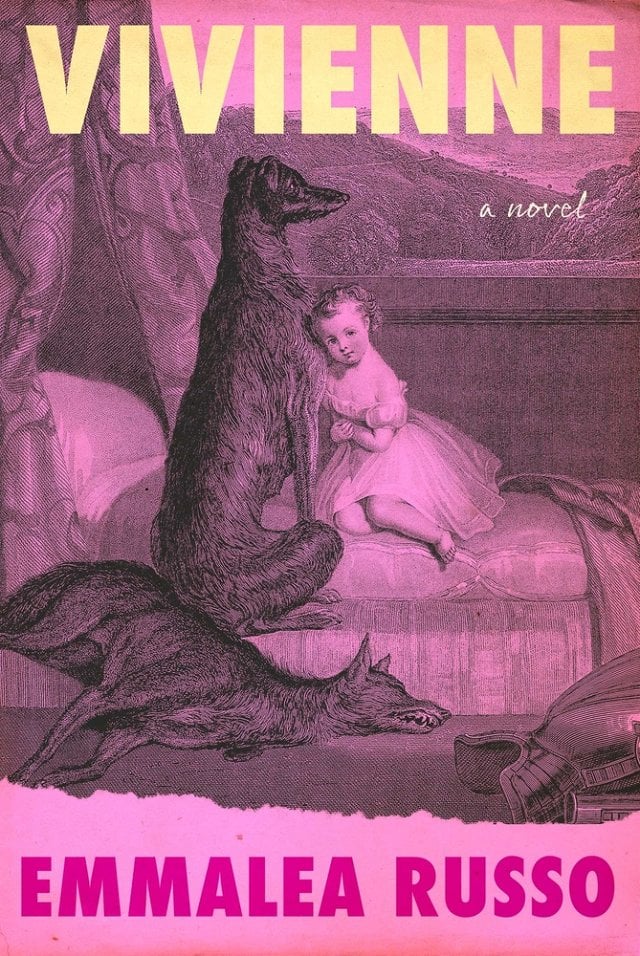

I was reminded of sitting up there on that altar while I read the poet Emmalea Russo’s debut novel Vivienne, which examines questions of guilt, absolution, and who, if anyone, we are ultimately answerable to. The titular Vivienne Volker is a charismatic textile artist who left the Parisian surrealist scene of the ’70s after the death of her boyfriend, the artist Hans Bellmer. Vivienne and Bellmer began their relationship to great controversy while she was in her twenties and he his seventies, though the true scandal came after the suicide of his ex-wife, Wilma Lang. Now in her eighties, Vivienne lives in rural Pennsylvania with her daughter Velour, her granddaughter Vesta, their dog Franz, and her much younger boyfriend Lou. She attends Mass regularly, smokes like a chimney, wears Miss Dior perfume around the house, and lives a simple life until her work is selected for inclusion in a retrospective exhibit—“Forgotten Women Surrealists”—at a prestigious New York museum. The internet erupts: “vivienne volker killed wilma lang.” In brief, she’s canceled.

Vivienne’s critics appear glancingly in the outset of the novel, writing, with the diction of high school seniors, a petition addressed to “All Who Stand For What Is Just” that accuses Vivienne of “[provoking] triggers” and of being a “dubious figure.” The museum responds that it will remove Vivienne’s work from the exhibit, because the institution “seek[s] to reduce art-induced distress.” Russo doesn’t pretend to take their arguments seriously. She doesn’t meaningfully flesh out criticism of Vivienne’s work (somewhat relying on readers to be familiar with real-world conversations about Hans Bellmer’s work), and never truly explains exactly why there are rumors that Vivienne “incited” her ex-lover’s ex-wife’s suicide.

Don’t worry: This novel isn’t a polemic against “cancel culture”—and thank God! I can’t imagine anything more tedious. Instead, Russo fashions a vast and ambitious world. Vivienne is an ekphrastic work that blends truth and fiction. The character Vivienne is a fictional creation of Russo’s, while Bellmer is a real artist whose real partner and collaborator, Unica Zürn, did die by suicide. The novel alternates between three genres: a multigenerational and multi-perspective family drama, a satire of the New York art scene, and a social media comment section. Within those sections, it meditates on guilt, faith, motherhood, family, the act of creation, the intrusion of the public into private lives, visions, and ghosts (holy and otherwise). Images and themes are often doubled: Two female artists are rumored to have been pushed out windows; two daughters grow up without fathers; four relationships occur between people with age gaps of over three decades; and the three women of the family all have visions (though they receive and interpret them very differently). There’s a lot going on, and the book doesn’t have the page count to develop all its ideas with equal conviction or to make the varying tones coalesce. Nonetheless, Russo’s elegant prose and clever plot make any unevenness forgivable, and it’s much more fun to read a novel with expansive aims, even if it doesn’t always hit the mark.

Russo’s art scene is delicious and dreadful, exaggerated so that it balances delicately only a note or two above the absurd. Lars Arden, a Manhattan gallery owner (an enterprise funded by his father, of course) whose “latest goal” is to “believe in and be moved by” the work he sells, approaches Vivienne after her work has been removed from the “Forgotten Women Surrealists” show, sensing an opportunity for spectacle, “something electric and scandalous.” He tries to convince himself that his motives are altruistic, that he’s “committing an act of great service” to the world by rehoming “a forgotten artist burned at the internet’s stake,” but he can’t finish watching one video about Vivienne’s work without falling asleep with his hands down his pants.

Lars’s world is one that Vivienne and Velour were both once part of, and have purposefully decided to abandon. Their life in Pennsylvania is not exactly quiet, but it’s humble, at least compared to the art world parties of their youths. The family scenes stretch mostly across four perspectives—Vivienne’s, her daughter Velour’s, her granddaughter Vesta’s, and her boyfriend Lou’s. Vivienne’s sections are compelling, detailing the inner life of an eighty-year-old artist made young again by the idea of her work being revisited. Vivienne is “charming, moody, and suddenly cruel, with capable technician’s hands and a bonkers artist heart.” She’s a practicing Catholic, though several characters—including her daughter Velour—question the sincerity of her faith. Vivienne, with her outsized personality, “sets the tone” of this household. Velour provides a more subdued commentary, the perspective of a daughter who has lived in her mother’s shadow. She spends her time researching her parents’ lives and works, while sitting in the chair where she found her husband’s body after an accidental overdose. Her seven-year-old daughter Vesta is precocious, curious, and overexposed to adult life. The family serves as the center of the novel, but their sections could use the most expansion. It is obvious that Russo has a clear vision of who these characters are and how they move through the world, and though their family dynamic is deftly drawn, all four characters (particularly Lou) remain somewhat enigmatic, their motives clearer to each other than to the reader.

Velour and Lou are the only two in the household who spend time reading the online comments and tweets about Vivienne—Vivienne is too old for social media, Vesta is too young. The comment sections are full of trolls, wokescolds, and schizoposters seeking good gossip, God, a savior for Western civilization, and companionship. Some posts are lyrical, some are funny, some are strange, and many are all three at once:

@survbapmessage

i performed open heart surgery but i am not a surgeon

never went to med school but i knew i could

do it the patient was Hans Bellmer

my hands had eyes and they were unsanitized

Volker stood over me watching my work

unimpressed hopeful Wilma was there, too

all died brutally me included

The comments are cleverly woven together, and, as the days pass, comments begin to build upon each other, and characters, even relationships, emerge out of a sea of anons. All of Vivienne is written with a poet’s economy and precision, but these social media sections especially reward a re-read.

Vivienne’s past—“those days in Paris”—peek tantalizingly through the present day of the novel. Vivienne remembers an early adulthood spent exhilarated by creativity, feeling “inhabited by a force which sucked out portions of her and replaced them, bit by bit, with more amplified, inflated energies.” Perhaps it’s a voyeuristic instinct in me—the same morbid curiosity about violence and tragedy that powers comment sections—that makes me wish Russo spent more time fleshing out Vivienne’s past. But Vivienne is the heart of the novel, and certainly its most interesting character. I don’t think it’s prurient to want to see more of Vivienne, or more of “the manic madness” of her youth.

I suppose what I’m really reacting to is the distance I felt from the characters of the novel. Even as the novel’s center, and even while the text is from her perspective, Vivienne remains somewhat of a mystery. Her reflection on the question of her own culpability in Wilma’s death is very brief. It’s a movingly ambivalent passage, made all the more compelling by how fallacious the allegations seem at the outset of the novel. The reader may not take them seriously, but Vivienne does, and believes them to be true “in a sense.” But even in this moment of reflection, the reader isn’t allowed to fully inhabit Vivienne’s feelings on the matter: We hear Vivienne’s reflection from the perspective of a child, her granddaughter Vesta, as they sit together in an empty church. It’s a gorgeous scene of communion between generations, but it’s over almost as soon as it begins. Vivienne steps into a confessional booth, and the curtain swings closed behind her.

R. M. N. Landry writes Book Notes, a blog on Substack. She is from New Orleans.

More Reviews