Allons! whoever you are come travel with me!

Traveling with me you find what never tires.

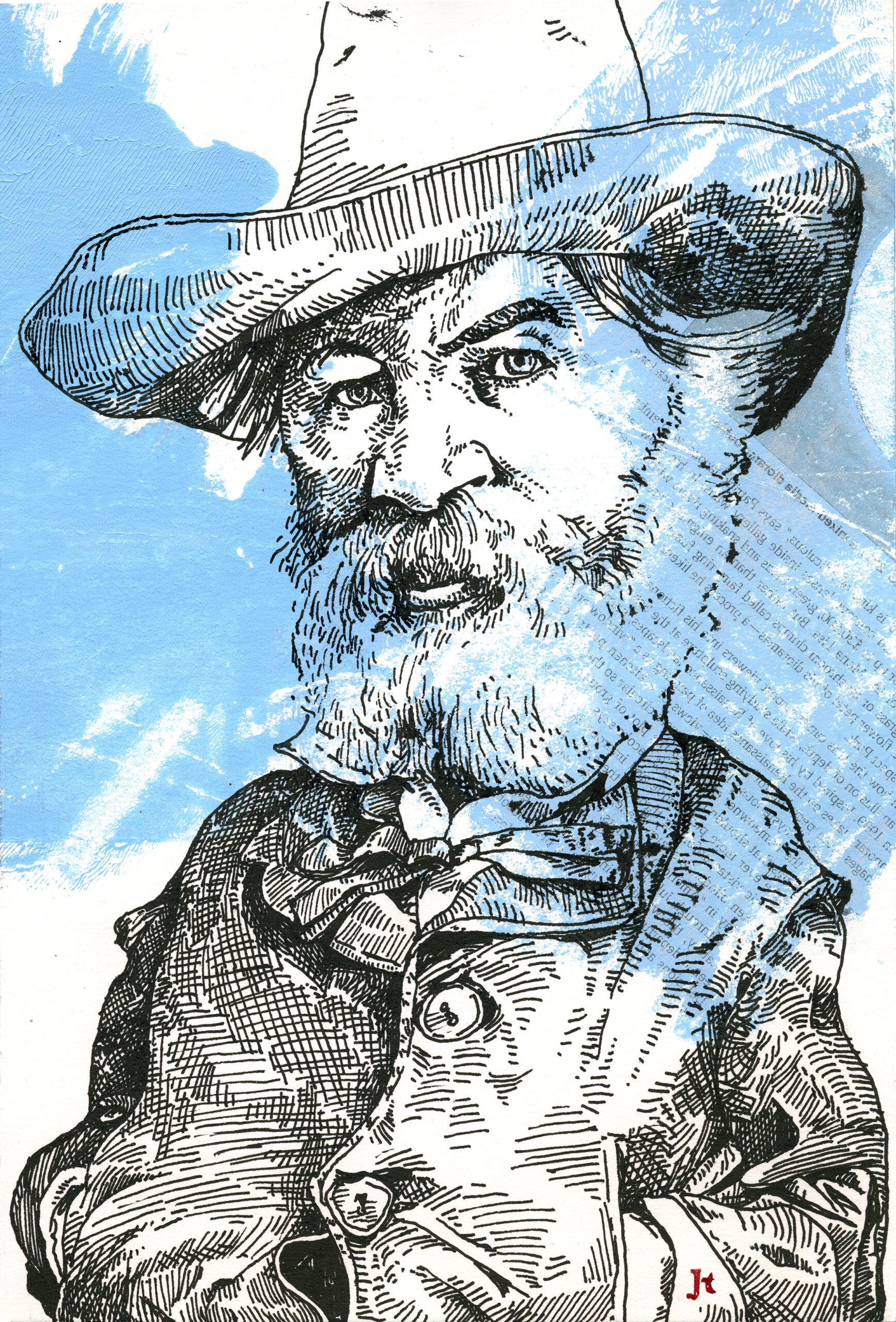

— Walt Whitman

Much like the speaker of Allen Ginsberg’s “A Supermarket in California,” I, too, have thoughts of Walt Whitman tonight. I, too, wonder where his beard points.

I cannot avoid him. I find in my Argentine self an American strain, though I bear no shred of American blood: my grandparents lived in New York for five years, from 1963 to 1968, but they returned to Argentina a month before their daughter, my mother, was born. In his final months, my grandfather told me, when I was American-college-bound, that returning to Argentina was his greatest mistake. Yet American life, cold and individual and work-obsessed, exhausted my grandparents. Though he died penniless, supported almost entirely by my parents (and a generous late-in-life partner), I don’t think my grandfather’s return was an error. I suspect that a part of me was driven northward, to America, in search of intergenerational vindication. Perhaps leaving Argentina was the point. Travel, the road, self-transformation: I have always dreamt of becoming American, but what I really wanted was to transcend myself. I learned, eventually, that the road that Yankees—habitually shameless—claim for themselves was mine.

Read Whitman to understand. The great explorer, the poet of America, the Yankee dandy. Whitman’s best readers were those to whom he did not address himself, who did not speak his language: Darío, Neruda, Paz, Martí, Borges, Mistral. Whitman begins his “Song of the Open Road” thus:

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

The road—not yet motorized or paved or transmogrified into an infrastructural behemoth by Eisenhower’s Cold War skulduggery—was just mud and horse shit, but it beckoned. The American road, unbuilt yet sung; Whitman, the great Faustian, marshaled his pathetic ecstasy into concrete fact, not for the first time or the last.

I have traveled these roads and seen the country’s emptiness, interrupted only by such byways. The Road and The Car were made into defining technologies of our vexed, decaying American age; we must not elude the truth of America’s emptiness, its fundamental stupidity and passionate intensity. Whitman’s great checkmate—that one cannot but rewrite him, one cannot but think of him by definition—is that of the road, too, of those I grew up wandering, not in the US but in Latin America. He writes:

They go! they go! I know that they go, but I know not where they go,

But I know that they go toward the best—toward something great.

We, his subjects, travel, though he knows not where to. The nation, Whitman’s nation, is both enclosed and extensive, never-ending and not quite infinite. Whitman’s nation was the United States of America, his roads the nascent hegemon’s horizontal arteries; his poetic expansiveness and orgasmic sense of the world, his refusal to foreclose its borders, allows me to claim his song. “Something great”: the Pan-American Highway, which runs from Tierra del Fuego to Alaska and passes by my family’s home in suburban Buenos Aires, or the blood-soaked road from Mexico City to New York. What’s the difference?

![]()

The road is, almost without question, the defining symbol of twentieth-century America. Its central protagonist, the automobile, is coterminous with the twentieth century, as is that other great technology of movement that inaugurated our epoch: film. Thomas Edison’s Automobile Parade, which portrays the first annual automobile parade in 1899, held in downtown Manhattan, premiered in 1900. By the early 1910s, the car governed film.

Though various inventors had proposed self-propelled vehicles starting in the mid-eighteenth century, it wasn’t until the “Gay ’90s” that the automobile crossed the Atlantic in force. By 1895, even as the inner mechanics of the vehicle remained unsettled—cars could be powered by diesel, coal, steam, even electricity—the automobile age had begun in full force. What the sociologist John Urry described as “the system of automobility” began to develop: “a self-organizing autopoietic, non-linear system that spreads world-wide, and includes cars, car-drivers, roads, petroleum supplies and many novel objects, technologies and signs.” Cars, but the world around them, too.

Yet, for all its globality (and the European origin of the automobile as technology and word) the “system of automobility” was, at birth, strictly centered in the United States. Detroit—home to the carriage industry in a prior century—was its capital. What had once been the province of inventors and madmen began to shift toward a highly concentrated industrial model. Frederick Winslow Taylor began to publish his theories of “scientific management” that year, which demanded the sophisticated mechanization and individualization of labor and provoked, by the 1910s, a widespread sense that workers were being reduced to “automatons” and inspiring a “politically debilitating” sense of the (white and male) worker’s “effeminacy,” as the cultural historian Cotten Seiler puts it in his magisterial Republic of Drivers. The sovereign, self-reliant Emersonian subject was replaced by the managed, emasculated factory operator, and a “post-individualist” society needed a “compensatory subjectivity characterized by self-determination.” The subject turned inwards, became “expressive” and, eventually, morphed into what the historian Charles McGovern termed the “sovereign consumer,” says Seiler: “It was a social self, but it looked like a sovereign self. Its characteristics were mobility and choice; and its embodiment was the driver.” To drive was the epitome of individual self-expression, a compensation for the outrages of industrial, optimized capitalism and its degradation (real or imagined) of subjectivity to machinery.

Such an experience was no novelty. Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road” appeared in the 1856 edition of Leaves of Grass, inspired by America’s colonial westward drive of that era. In 1893, only two years before the automobile arrived in the US in force, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner delivered his “Significance of the Frontier in American History,” exalting the utopian expansionism of the nineteenth-century United States and rooting the nation’s character in its mobility and settlers’ rugged, individualistic adaptability. In that final decade of the nineteenth century, as the scholar Amy Kaplan documented, imperialist romance novels featuring “swashbuckling . . . knights errant” dominated the literary market and produced a spectacular (even “expressive”) masculinity. Romance heroes displayed their virility in the rescue of endangered heroines from racialized, foreign adversaries. Taylorist optimization optimized the American man, for whom the car was a vehicle for the technological perfection of imperial desires developed over the previous century.

By the 1930s, automobility owned America; the car was returning its drivers to a wilder age, all speed and individual autonomy. Though the car would become an eminently male domain, in its early days it was, to some degree, effete and aristocratic, even open to use by women, many of whom completed the first cross-country drives in the US. But as the car swept the nation and became increasingly popular and accessible to the lower classes, it recovered its masculine, anti-domestic aura.

![]()

As Seiler documents, the Cold War raged and the Truman and Eisenhower administrations were “convinced that the outcome . . . depended upon the vitality of American individualist virtue.” The Great Depression and subsequent abundance of the 1940s “warfare-state economy” provoked a sense of resurgent collectivism and fraying individualism. Such weakness would not fly in the civilizational fight against communism. The Eisenhower administration developed the Interstate Highway System (IHS), starting in the mid-1950s, and sold it as a highly democratic project for the establishment of the (white, male, middle-class) American individual through automobile mobility. To drive was, in some sense, to assert the primacy of democracy (i.e., capitalism) against the ever-encroaching collectivist anomie; to will into being, through the aggregate individual agency of the country’s entire population (of which the IHS was the physical articulation) the triumph of white and male Americans against the Soviet Union and communism writ large.

Around the same time, the road novel became the central genre of countercultural literature almost overnight thanks to the popularity of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, published in 1957, though written some years earlier and portraying events that transpired in the late ’40s and early ’50s. The novel conceptualizes the road as a space of self-discovery and transcendent exploration, a space of pure, quasi-Romantic vitality that made possible a kind of cognitive, even affective elevation. It was also a space of unpredictability and danger, of Whitmanic encounter with the gamut of American society’s underbelly, of that which “the system” or “the man” obfuscated in everyday life. Dean Moriarty, novelistic pseudonym of the Beat and counterculture icon Neal Cassady, is a sexually titanic, hyper-virile asshole, a radical individualist unable to “settle down” or behave with minimal decency toward the friends, lovers, and children he constantly abandons. He is, theoretically, searching for his father, a wandering “wine addict” living on the streets of Denver. The narrator—Kerouac’s cypher, Sal Paradise—makes sense of Moriarty’s “criminality” as a “wild yea-saying overburst of American joy; it was Western, the west wind, an ode from the Plains, something new, long prophesied, long a-coming (he only stole cars for joy rides).” Beyond Paradise’s obvious analogy (Dean Moriarty as the embodiment of manifest destiny, inseparable by name from death), the affective emphasis on vitality is remarkable. Much like Jim Stark, James Dean’s character in 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause, which premiered in 1955, Moriarty is a daredevil and an idiot, wise beyond his years and stupid beyond belief. A child that can drink and fuck and smoke, for whom rejection of parental and societal expectation is, itself, a mandate.

In both book and film, cars and driving allow for the development and even resolution of adolescent homosocial energies. In the latter, a race to see who will brake first leads Jim Stark’s rival to drive off a cliff to his death. In the former, cars (stolen, borrowed, bought) are an enclosure in which Dean Moriarity and Sal Paradise can fulfill their various aesthetic and personal aspirations—finding Dean’s father, getting away from or going toward their wives and ex-wives and partners—but also where they can sort out their own conflicts with each other. The car is the conduit through which to encounter a more real reality, that which the forced conformity of postwar American society secreted away.

Yet if On the Road was received as a paean to male juvenile adventurousness and an epochal affirmation of postwar prosperity—and the alienation such abundance produced—it is also a story of disillusionment, of the adolescent terminus. The novel begins with Paradise’s “split up” from his wife and overcoming “the miserably weary split-up and my feeling that everything was dead. With the coming of Dean Moriarty began the part of my life you could call my life on the road.” Electrified by the possibility of the journey west into which Moriarty enlists him, what follows are a series of misadventures and, in the end, the break, when Dean is not allowed in Sal’s friend’s car and he must watch Dean wander away, aimless and alone:

So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast . . . I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.

Moriarty, never found and always lost; Moriarty, Kerouac’s America.

![]()

Yet my goal, as I set out on this essay and journey, was not to understand America as Americans see it, with roads as messianic pathways to some Western land of God and affirmation of a rather selfish, individualist, and misogynistic vitalism, but rather to exploit their paths for my own purpose. To understand myself, my tradition—if “Latin America” can be said to even exist and have such a tradition—as not only existing in some degree of relation to the American tradition and apart from it but even within Kerouac, or James Dean, or any of the icons of the American road.

Travel narratives like the road novel are, arguably, the foundational genre of writing of the post-1492 Americas. Colonial relations by conquistadors Columbus, Cortés, or Vespucci among many others had to both document the New World at the moment of its discovery and guarantee property claims for all involved. Accounts of their exploits were once the principal source of European knowledge about the New World, and travel narratives remained central to the canons of emergent Latin American nations centuries later. Argentina’s post-independence process of settler-colonial expansion and Indigenous extermination, the “Conquest of the Desert,” relied on travel narratives that portrayed the land to be conquered as deserted. Manifest destiny, with its echoes of Puritan messianism, did not extend toward Catholic Argentina; instead, the Conquest of the Desert was framed within a project of secularizing modernization articulated in the famous opposition by the writer and Argentine president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento: civilization or barbarism?

At a broad, regional level, many of these travel narratives—Lucio V. Mansilla’s An Expedition to the Ranquel Indians; William Henry Hudson’s Idle Days in Patagonia and The Purple Land; Euclides da Cunha’s Os sertões (translated as Rebellion in the Backlands); Manuel Ancízar’s La peregrinación del alpha; Luis Malanco’s Viaje á Oriente among many others—were directly connected to settler-colonial political projects and written mostly by soldiers and politicians. Even more transparently literary works, like José Hernández’s Martín Fierro or the “Anacleto Morones” section in Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, featured travel heavily to reflect—and instantiate—the region’s ambivalent transition into what the recently deceased literary critic Beatriz Sarlo termed a “peripheral modernity” by the early decades of the twentieth century. Some more explicitly novelistic works of the period could also be conceived as proto–road novels, or at the very least travel narratives: for instance, Colombian José Eustasio Rivera’s La vorágine (The vortex), published in 1924, features an aristocratic woman fleeing Colombia’s oppressive upper class toward the jungle with the impoverished poet she has chosen to marry. Though the road—proof of already settled and dominated land—is not, yet, a protagonist, the proto-countercultural, avant-gardist rejection of “proper” societal expectations in favor of the bohemian poetic life was already becoming manifest.

![]()

It’s worth pointing out, however, that in the (allegedly) more egalitarian midcentury United States, the countercultural gesture mostly manifested through the Beats’ petit bourgeois milieu, rather rigorously white and imaginatively masculine. In the radically unequal Colombia, as in the rest of Latin America, it can only be a bourgeois, even aristocratic gesture. Only the wealthy—or the truly subaltern—can truly afford to leave society. If Kerouac’s On the Road singlehandedly shot the genre into popularity in the US (and, with translation, elsewhere around the world), then the book that did much the same for Latin America’s road tradition is the Argentine Cuban revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s Notas de viaje (Notes from a journey), published in 1993 but based on a diary he kept as he and his friend, Alberto Granado, traveled the continent from Buenos Aires to North America in 1951 and 1952. Even though they were published posthumously, Guevara’s journeys across the continent were widely known and mythologized while he lived, and he himself edited them into book form. Although their publication was delayed for decades, the journeys themselves were almost contemporaneous with Kerouac’s own “life on the road,” and express a similar countercultural gesture.

Indeed, both texts bear remarkable tonal and structural similarities. Though one is a novel and the other an edited travelogue, both feature a narrator who sets out on a journey with a friend, framed as a kind of byway into adulthood. Kerouac’s relationship to jazz has been extensively documented, with On the Road featuring multiple scenes at jazz clubs like Birdland and its prose style inspired by its improvisational structures of that music, with sentences like “licks.” Guevara’s prose is simple, as befitted a putatively ascetic revolutionary, but in explaining the inspiration of his journey, Guevara writes:

“Why don’t we go to North America?”

“North America? But how?”

“On La Poderosa, man.”

The trip was decided just like that, and it never erred from the basic principle laid down in that moment: improvisation.

The decision to set off on a journey is narrated rather equally as impulsive as Sal Paradise’s, and the language of improvisation stands out in relation to Kerouac. Guevara may not be an artiste, and calling him jazz-influenced is a stretch, but the parallel emphasis on improvisation is remarkable. Though Guevara did not set out in search of a literary subject, his road—a journey from San Francisco, in the province of Córdoba, down to Bariloche, up through Chile, and concluding in Caracas—is certainly a project of spiritual transformation akin to Kerouac’s. Guevara himself makes his objectives clear at the outset:

In nine months of a man’s life he can think a lot of things, from the loftiest meditations on philosophy to the most desperate longing for a bowl of soup—in total accord with the state of his stomach. And if, at the same time, he’s somewhat of an adventurer, he might live through episodes of interest to other people and his haphazard record might read something like these notes.

Kerouac and Guevara also share a predilection for intoxication. Though Guevara doesn’t smoke pot or consume other substances, he and Granado consume prodigious volumes of wine and share the picaresque Beat penchant for the procurement of food: in their case, they say that, in Argentina, drinking without eating something is seen as rather uncouth, which often gets them fed and even housed. Though Guevara spent his life loathing the United States, and his lifestyle in the ’60s likely didn’t leave him much time for pleasure reading, one wonders if he read On the Road.

However, the two books differ sharply. For starters, Guevara’s diary sets out a singular journey with a relatively clear destination (“North America,” which ultimately resolves into Venezuela) while Kerouac’s concerns a series of journeys across the United States, despite its emphasis on the “West” as a spiritual endpoint. While Guevara suggests that “All this wandering around ‘Our America with a capital A’ has changed me more than I thought,” contextualizing his experiences within a (Whitmanic, like it or not) tradition of Latin Americanist and anti-US thought whose inklings reveal themselves in the text: Guevara quotes or paraphrases Marx, Neruda, the Venezuelan poet Miguel Otero Silva, the Cuban revolutionary José Martí, and others—writers, sure, but also avowed leftists. As he travels the continent, he notices and apprehends its structuring injustices, from exploited mine workers in Chile and Peru to lepers (Guevara, though he did not quite yet have his medical degree, was training as an expert in the condition) and farmers. When Kerouac encounters migrant farmworkers or the homeless, poor and destitute, black and white and Mexican, he does not reflect upon structural conditions; instead, the encounters with difference are narrated as fascinating and exotic, the enclosure of the car and the restricted space of the road allowing Kerouac to push past anything resembling historical or social context and to make a quick getaway thereafter.

Indeed, Guevara famously rode “La Poderosa,” Granado’s crappy Norton motorcycle, which is literally open to the world. Not to mention that “La Poderosa” has an impressive number of technical issues and all manner of accidents before permanently breaking down in Chile around the time Guevara acquired his iconic nickname. Thereafter, the two travelers, always broke, must embrace any mode of transport possible: truck, bus, airplane, kayak, boat, raft, anything to keep heading North. The famously anti-communist On the Road is a paean to “driving” as Seiler understands it—putatively democratic but emptied of difference, a hypermasculine assertion of capitalist America’s primacy and the white American man’s independence—then Guevara’s is truly Whitmanic in spirit: a road poetry of encounter and universal curiosity, an engaged openness to the true discovery of the other, of the possibilities that encounter allows.

I don’t mean that Whitman was a militant revolutionary (he certainly wasn’t) or that Guevara’s revolutionary energies are, themselves, Whitmanic. Indeed, for all of Guevara’s left-wing cred, it’s notable that the déclassé aristocrat—whose family tree threads Argentina’s history—sets off on October 17, the day of Peronist loyalty. Peronism, undeniably a working-class movement, was (not incorrectly) seen by leftists at the time as an anti-communist, anti-revolutionary capitalist force. Yet Kerouac’s role as the “father” of the modern road novel betrays a central pillar of the genre’s potential that Guevara does not squander: its capacity to serve as a thruway to encounter, to provide an account of oneself, bourgeois warts and all, making sense of other lives in their human fullness. To understand the world and resolve to change it.

![]()

Yet the Motorcycle Diaries are by no means the only road narrative in Latin America. Mexico’s Beat-influenced literary movement, derogatorily termed Literatura de la Onda by Margo Glantz, had at its forefront Parménides García Saldaña, whose first novel, Pasto verde (Green grass), was published in 1968, the year in which Mexico’s student movement reached its summit with the brutal Tlatelolco Massacre of demonstrators carried out by military and paramilitary forces. García Saldaña’s story of a young man named Epicuro flouted literary conventions with its unapologetic Spanglish and interest in smashing the US and Mexican cultures together while rehearsing what I’ve been calling the countercultural gesture of taking to the road.

Other writers across the region took up the form: Osvaldo Soriano, a stalwart of Argentina’s liberal left whose writing Bolaño once suggested (correctly, I add) would be forgotten, published Shadows in 1990. In that novel—written with Soriano’s distinctive mopey sentimentalism, blurbed by John Updike and adapted into a film in 1994—an Argentine computer engineer returns to his home country from Europe, where he has a prestigious job, and soon finds himself lost on Patagonian roads, needing to make it to Neuquén. Guillermo Saccomanno, in a preface, called the novel “a moral tale, a fable that implacably reflects the tensions of a country facing its downfall” (translation mine). That country, of course, was Argentina in the aftermath of its early 1980s, postdictatorial “democratic spring,” plagued by hyperinflation and economic immiseration. The Argentine novelist Mempo Giardinelli’s Final de novela en Patagonia (Novel’s conclusion in Patagonia) likewise concerns an adolescent road trip southward toward the once-Indigenous, now-colonized lands of Patagonia, a habitual space of pilgrimage for the children of the Argentine counterculture. Mariana Enríquez’s brilliant Our Share of Night focuses heavily on a road trip to subtropical Northeastern Argentina, while Mexican authors and ex-husband-and-wife duo Valeria Luiselli and Álvaro Enrigue each novelized a road trip taken together from New York City to the Southwestern US: Luiselli’s novel, Lost Children Archive, observes the migrant crisis, while Enrigue’s Ahora me rindo y eso es todo (Now I surrender to you and that is all) uses the story of the extermination of the Apache to explore a longer history of the US-Mexico border. Forget not: much of the US, from Florida to California, was once—and, I’d argue, still is—Latin America.

Yet if there is a defining Latin American road novel, it is without question The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolaño, published at the turn of the millennium and immediately hailed as a classic. A roman á clef like On the Road and its other forebear, Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, The Savage Detectives is about Bolaño and his friend the poet Mario Santiago, fictionalized as Arturo Belano and Ulises Lima, who flee Mexico City northwards in search of Cesárea Tinajero, a mysterious, mythical “Visceral Realist” poet who has vanished from sight. The Savage Detectives also echoes Guevara’s story, with Belano—like Bolaño—traveling by land to Chile in the days of Pinochet’s coup and back to Mexico and ultimately meeting his apparent death in Angola. Belano, Lima, and the narrator, García Madero, come of age throughout the novel and eventually find Tinajero in Sonora, only for her and Lima to die in a shooting. The novel—a loving satire of the “poetic life” and gravitating around three aspiring poets’ search for a fictional poet—dramatizes the tension at the heart of On the Road, Motorcycle Diaries, and even Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road”: the commitment to the search, the road—and, here again, the car (this time, an Impala)—as a conduit to freedom or the transformation of oneself. Poetry itself, Bolaño suggests, is the journey and the road. How else could one make sense of Tinajero’s famous visual poem, its road-like squiggle and car-like cube?

![]()

Of course, novels are not the only form of road narrative—as I said early on, the link between the car and the movie camera is profound, and this is especially the case in Latin America. The two defining films of the genre’s recent history, predictably, bear an intricate relationship to the works I’ve discussed above: the Brazilian director Walter Salles’s 2004 adaptation of Che Guevara’s diaries, Motorcycle Diaries, and the Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón’s Y tu mamá también, from 2001, which shares a kinship with Bolaño’s novel. As the film scholar Nadia Lie has argued, the two films followed a boom period for Latin American film writ large in the ’90s, but the road movie genre’s simplicity is uniquely suited to the resource scarcity that filmmakers in the region were accustomed to working with while providing a globally legible generic frame within which they could tell regionally specific stories. Lie points out that the genre allows filmmakers (others who have participated in the genre include Fernando “Pino” Solanas, Pablo Trapero, Alberto Fuguet, Marité Ugás, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Carlos Sorín, and Alicia Scherson) to reckon with the ambivalent effects of late-capitalist modernization. The films, frequently cofunded by Europeans, are thus “both an expression of modernity and an ambivalent meditation on it,” Lie suggests.

Y tu mamá también is the story of two wealthy childhood best friends, Tenoch Iturbide (Diego Luna) and Julio Zapata (Gael García Bernal), who take an impulsive road trip to a fabricated beach near Puerto Escondido, in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, to impress Luisa Cortés, an older Spanish woman played by Maribel Verdú. Their origins are, to some extent, characteristic of neoliberal 1980s Mexico: one is the son of a high-level politician accused of corruption, the other the son of a progressive, middle-class family. Their relationship will fray irreparably as they vie to seduce Cortés, the car not a Kerouac-esque space of emancipation but an enclosure for their differences to smash against each other. Y tu mamá también thus reads as a reflection on the collapse of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), which ruled Mexico for much of the twentieth century but was consumed by allegations of corruption, enduring a raucous split in 1988 and an ultimate loss of power in 2000. The road shelters the movie’s protagonists, who, out of keeping with the Latin American tradition, do not encounter difference outside of their borrowed car. Instead, they find difference and incompatibility among themselves, and become a microcosm of Mexican politics and culture writ large.

Salles’s Motorcycle Diaries, meanwhile, revisits the figure of Che Guevara—also played by García Bernal—and renders the revolutionary-icon-cum-trademark an inoffensive, generous, and charitable young man with a large heart. He’s a romantic, an intellectual, no threat, just a wandering soul curious about his place in the world. Though encounters with lepers and brutalized mine workers are not excised, and the development of Guevara’s political consciousness is clear, the film’s success—including the Oscar for Best Original Song—attests to its political tameness. Salles’s Guevara is more like Sal Paradise than like the real Che, a requiem for the failure and, frankly, extermination of the revolutionary left in Latin America in the previous decades. Tellingly, in 2012, Salles directed the first-ever film adaptation of On the Road, with a script written by a fellow Latin American, the Puerto Rican playwright José Rivera, and conveniently laundered of much misogyny and racism.

![]()

But I have withheld my discussion of the central role that Mexico plays in On the Road—indeed, in the Beat movement writ large. My hope, I said, was to make sense of my own Whitmanic legacy: not just road stories written by my forebears, but our presence in those texts canonized as ur-American.

Early in the book, Kerouac narrates his love affair with a poor Mexican seasonal worker, whom he erotically exoticizes and quickly discards in his search for what the Chicano writer Manuel Luis Martinez describes as “a sense of mission, patriarchal power, and primal freedom.” As Martinez has argued, the work of Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg are all, in different ways, defined by “a neo-individualism fueled by a neo-colonial imperative” that understands Mexico as a site for “New Imperialism” and a renovated frontier, not west but south. For On the Road’s narrative climax, Paradise and Moriarty travel to a brothel in Mexico, where they drink, party, and have sex with underage prostitutes before running away without paying. Kerouac’s sentences balloon in Mexico, fill with an even greater sense of ecstatic fulfillment, and it is in Mexico—and only in Mexico—that any shred of social consciousness seems to strike Paradise:

The mere thought of looking out the window at Mexico—which was now something else in my mind—was like recoiling from some gloriously riddled glittering treasure-box that you’re afraid to look at because of your eyes, they bend inward, the riches and the treasures are too much to take all at once. I gulped. I saw streams of gold pouring through the sky and right across the tattered roof of the poor old car, right across my eyeballs and indeed right inside them; it was everywhere.

He sees the poverty around him, apprehends his own whiteness and difference, but is unable to truly make sense of it and must recast it as “some gloriously riddled glittering treasure-box”—yet another enclosure. What does such a glimmer of consciousness provoke? Eventually, the collapse of Paradise’s relationship with Moriarty; but first, of course, stiffing the poor sex workers and giving a few bucks to some cops nearby instead. So much for encounters with difference, huh?

![]()

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which has built and improved roads across the Third World, enrages the Yanks because it takes their symbol away from them. Our century seems likely not to be American but Chinese, yet what Eduardo Galeano called the “religion of the automobile” proceeds apace.

Who, then, should be Whitman’s children? Whose tradition, whose world is more properly Whitmanic? It’s a trick question, of course—we are all his children, we cannot help but think of him, sing his “Song of the Open Road,” wander in search of true companionship and radical self-transformation as the world crumbles into fascism or its farce.

Camerado, I give you my hand!

I give you my love more precious than money,

I give you myself before preaching or law;

Will you give me yourself? will you come travel with me?

Shall we stick by each other as long as we live? ![]()

Federico Perelmuter is an essayist and critic from Buenos Aires, Argentina. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Baffler, and Parapraxis, among others. He is a contributing writer for Southwest Review and is at work on a book project about the history of metal extraction in the Americas.

Illustration: Jonathan Twingley