A Couple without Qualities | Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection

Reviews

By Conor Truax

On Christmas Eve of 1938, bereft after the recent loss of his father, which had thrust him into a creative crisis, Jorge Luis Borges walked aimlessly into a window frame that jawed a large piece of flesh from his head. The wound quickly became infected, giving way to a bout of septicemia that he narrowly escaped. As he recovered from his brush with death in a fevered paranoia, Borges became convinced that the spotless window had damaged his brain irreversibly; that he’d permanently lost his ability to speak, reduced now to communicating in wordless grunts; and that he was to become insane forever after.

The fever subsided, his speech returned to him, and Borges set out to test the extent to which he’d lost his mind, his sensibilities, and most important, his creative faculties. The product of his self-evaluation was a very short metafictional story of the now widely regarded Borgesian variety called “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote.” “Menard” is an epistolary story in the form of a critical obituary for the titular French Symbolist Menard, a composite character styled after Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Valéry. Menard, it is written, is so inspired by Novalis’s dictum that he has only ever really “understood a writer” when he is “able to act in the spirit of his thoughts,” that he decides to rewrite an identical version of Quixote by inhabiting Cervantes’s consciousness.

At first, Menard attempts to mimic the life and language of Cervantes under the deterministic pretense that by experiencing the life beats of his predecessor, he will be able to organically repeat his output (a conceit more recently replicated in Season Two of Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal). Eventually, although obviously impossible, we are told that Menard abandons his initial project because he believes it is “too easy.” Instead, he seeks to write through the prism of his distinct life experiences—and his distinct position in history—to produce and justify the same sequence of words as is found in Cervantes’s original text.

“Menard,” alongside Borges’s later story “The Library of Babel,” is paradigmatically concerned with the generative nature of authorship and chance, and the regenerative nature of influence and fate; the former finds meaning in both, while the latter—its spiritual counterpoint—is more cynical. Despite Pierre Menard writing a version of Quixote that is identical to the original, his obituarist considers the later version superior in essence because of the conditions of its production; a perfect remake and a superior adaptation. The adaptation, it is implied, is a genre keenly distinguished from the remake—“those parasitic books that set Christ on a boulevard, Hamlet on La Cannabière, or Don Quixote on Wall Street.”[1]

Borges represents Menard’s Quixote as an ideal text that is both a perfect adaptation and a perfect remake—an impossibility rendered palatable by the slippery playfulness of the author’s genius, with an irony that masks the self-evident farce of Menard not having translated Cervantes’s original text at all.

But Borges points toward an important distinction not often considered within the literary form: typically, adaptations are considered as being translations between forms (e.g., a literary adaptation into film), whereas remakes are considered as being replications within them (a shot-for-shot remake).

However, “Menard” makes implicit the existence of intraformal adaptations, and defines them (by way of Novalis) as being driven by an embodiment of consciousness that permits the spirit of an original text and its author to be translated through a new consciousness that produces an original work, even if it means altering the fundamental structure of the original to accommodate the historical distance between it and its adaptation. On the other hand, a remake involves a much more straightforward reconstruction, with most changes in content being basic—and often crude—substitutions of historical reference and place.

Whereas much has been said about Hollywood’s net-zero economy of recycled ideas, there is less contemporary writing concerned with literary adaptations and remakes, despite their growing prominence and their long history—a history that spawned the structuralist methodology of critical evaluation, and that tends to be grounded in retellings of Biblical stories and ancient mythologies or histories. (For the former case, think Leo Tolstoy’s The Gospel in Brief, John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers, and more recently Karl Knausgaard’s A Time for Everything. For the latter, consider much of the works of Roberto Calasso and Marguerite Yourcernar, The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood, Oreo by Fran Ross, and of course James Joyce’s Ulysses. And all of this is to say nothing of Shakespeare.)

In recent years, however, there has been a turn toward the Western canon’s recent history, one more inclined to the national mythos and modern mundanity, and less to creation stories and God. Last year, Percival Everett’s James reimagined Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim and won popular acclaim as Barnes and Noble’s book of the year, while winning critical acclaim with both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction; in 2023, Demon Copperhead, Barbara Kingsolver’s modern Appalachian reimagining of Dickens’s David Copperfield similarly won the latter prize. Both adaptations leverage a perspectival reconfigurement to interrogate considered histories, whether recent or further into the past.

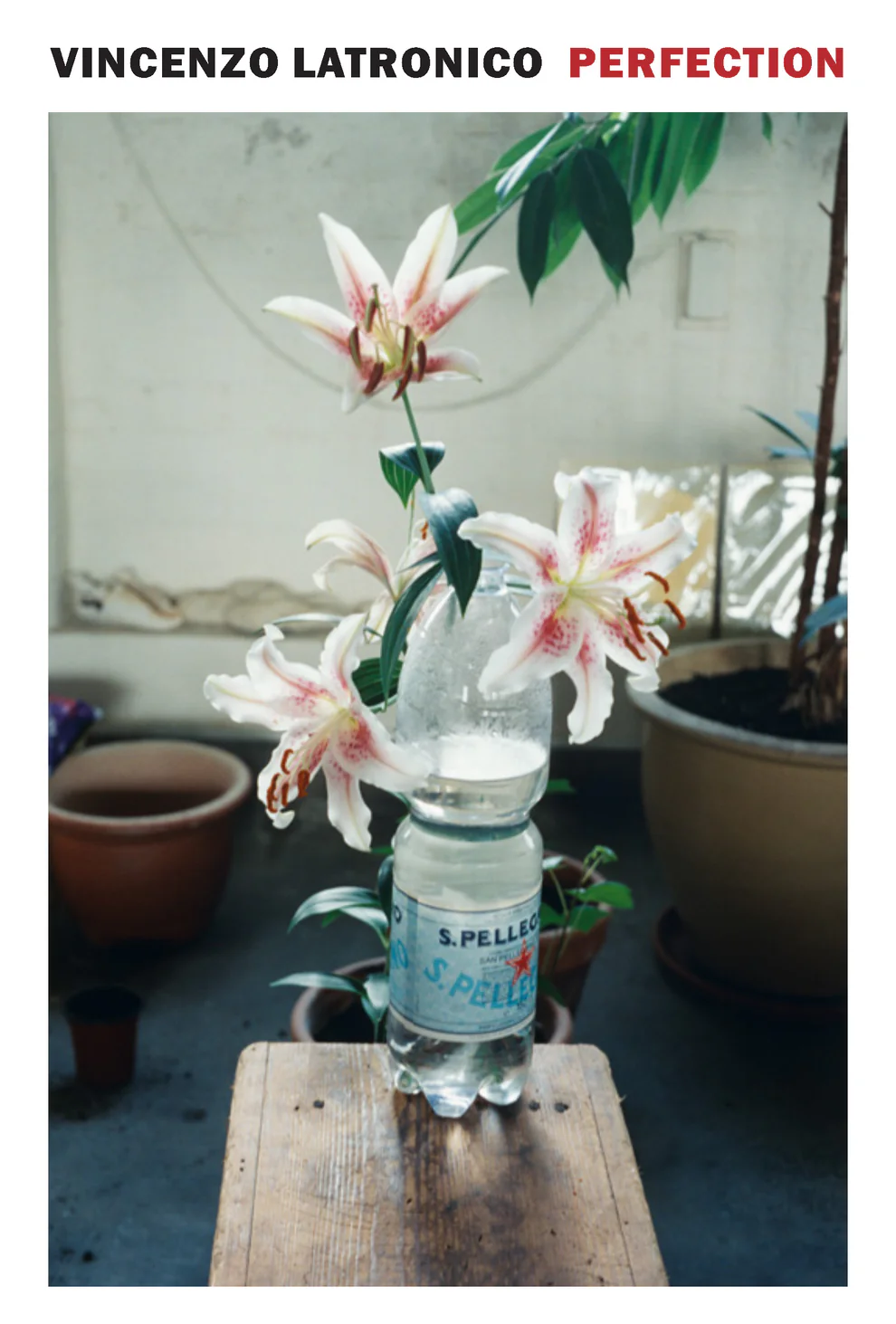

Now a newer adaptation has arrived: an oblique descendent of Borges whose discerning audience will be markedly narrower than those aforementioned texts. Vincenzo Latronico’s Perfection (2025) is a modern retelling of Georges Perec’s pre-Oulipo debut, Things: A Story of the Sixties (1965), and has enjoyed immediate critical success; only ten days after its UK release, it was longlisted for the International Booker Prize, where it now remains on the shortlist. It is a story about a generalized couple adrift in history—to use Robert Musil’s term, “a couple without qualities,” whose prime commitment is to their lack of conviction. They are, for all intents and purposes, the digital nomad’s Adam and Eve.

But on a structural level at least, their story owes a great debt to Perec’s Things, itself “a sociology of the quotidian” that tells the story of Sylvie and Jérôme, two middle-class market researchers in their mid-twenties lost in the chasm between their desires and their material means. The couple’s image of success is informed by global appeals—British tailoring and American films—that are pure simulacrum. They do not ascribe to the sartorial ideal “of the English gentleman, but the utterly continental caricature of it presented by a recent emigrant on a modest salary.” Likewise, they do not know any Americans but think “the lives they would lead would be as magical, as flexible, as whimsical as American comedy films or title sequences by Saul Bass.” Their lives, it seems, are always at least one remove from reality.

“The vastness of their desires paralysed them,” Perec writes, but not because they believe their desires are unattainable; rather, “the mere prospect of the work involved scared them.” Hence, after first presenting Sylvie and Jérôme as striving dreamers, Perec constructs their image as people whose frustrations are never at parity with the energy needed to overcome their circumstances, because their ultimate desire is not to overcome their circumstances; it’s to overcome desire itself.

Perec’s debut is striking for the ethnographic assuredness of his authorial voice, a “passionate coldness” he derived from Flaubert that is clinical but neither outright diagnostic nor condemning. The book begins with a detailed description of the couple’s apartment, and they are not given names until the book’s second chapter. Their lives are detailed in the habitual past tense in sentences often beginning with “They would,” and the languor of their passive history is punctuated by conditional statements that hypothesize what might emerge from the tawny agar of their petri-dish lives, if only they had the courage to broaden their experiment.

Politics has little recourse for Sylvie and Jérôme; they once participated in student protests against the Algerian War and the coming of Gaullism. By the time of the novel’s events, however, they have succumbed totally to their world’s consequent consumerism. They move briefly to Tunisia in search of adventure or purpose, but they’re quickly bored by their routine, which is restricted to a facsimile of their Parisian life in Sfax’s French quarters. As soon as they leave, they reflect wistfully on their experience: “They will tell all about Sfax, deserts, splendid ruins, how cheaply you can live there, the sea so blue.” The novel concludes with a future-tense epilogue that ambiguously describes their move to Bordeaux after a windfall puts an advertising agency in their lap. They leave Paris to begin their new, “real” life, accoutred with buffets of vulgar pleasure, everything being different and nothing having changed.

There is general consensus that Borges was a, if not the, major inciting influence on Perec, and Perec openly acknowledged that “The Library of Babel,” the fraternal twin of “Menard,” was the primary inspiration for his later semi-autobiographical novel W, or the Memory of Childhood. To those familiar with Perec, it seems self-evident that he would have taken no issue with adaptations of his own work; his experimental memoir I Remember, published in 1978, mimicked the methodology employed by Joe Brainard’s original I Remember from 1970.

While both memoirs are composed of simple declarative sentences that begin with “I remember,” the cause of their differentiation is clear: the life experiences that Joe Brainard donates to the anaphoric scaffolding are markedly different in both sequence and content than Perec’s. Perec even goes as far to say in an epigraph that beyond the title and form, “to a certain extent, the spirit of these texts [is] inspired by . . . Joe Brainard” (emphasis mine).

Likewise, Latronico’s Perfection begins with an epigraph from Things, and it follows from there with relatively strict formal adherence to its original, although in this case the couple’s living space is introduced by a description of images posted on an apartment-sharing website, taking the reader another remove from reality. Apart from small historical updates like these, it is difficult to immediately identify how Perfection has been adapted to capture a more contemporary zeitgeist, or whether the essence of the contemporary zeitgeist is any different than that depicted in the decade distilled by Things: “‘Impatience,’ Jérôme and Sylvie think, ‘is a twentieth-century virtue.’”

Similarly unnamed until the novel’s second chapter, Anna and Tom are a millennial couple from a “peripheral city in Southern Europe” who, we are told, had taught themselves Photoshop, Flash, JavaScript, and CSS as they came of age alongside social media’s earliest incarnations. As young adults in the early aughts, they moved to Berlin’s hip Neukölln neighborhood, where they are able to leverage their “passion” into a living as multi-hyphenate creatives: graphic-designers–brand-strategists.

Like Sylvie and Jérôme, they apply their specialized knowledge to lube the machinery that manufactures their consumptive desires, but lack the requisite distance to reflect meaningfully on its effects: “They could name every single [social media] update—the introduction of likes and notifications, video sharing, picture posting, tagging. But any attempt to draw a connection between those minutiae and the way in which social media had spread through every aspect of their lives was so reductive as to miss the point entirely.”

Berlin’s gentrification reaches new heights with an onslaught of Brits and Americans, native Anglophones who colonize the expat Berliners’ de facto lingua franca, chosen for being common to all and native to none. A search for broader purpose, much like Sylvie and Jérôme’s sojourn into student activism, is met with limp defeat: amid the Syrian refugee crisis in 2015, the pair are helpless to contribute their specialized share: “Anna and Tom offered to typeset [a basic German–Arabic phrasebook], but someone else got there first.”

Rather than a stint in Tunisia, Anna and Tom embark on a peripatetic stretch of remote work in Lisbon, then Sicily, where they hope to locate a less-gentrified and hence hipper and cheaper home base, one that is similar to their first experience of Berlin. When the back half of their trip ends in “the unhappiest [months] of their relationship,” they return to Berlin depressed, where winter spreads its reaches across spring.

Like its forebearer, the novel’s epilogue transitions to future tense. A similarly unexpected windfall sees Anna and Tom inherit a rustic country home on what is implied to be the Amalfi Coast, which they convert into a picture-perfect holiday rental. While Perec’s story ends by describing a sumptuous but tasteless meal, Latronico’s conclusion sees Tom and Anna achieving their desire: to live in a place that, in fleeting moments, “is just like it is in the pictures.”

Stylistically, Latronico duplicates Perec’s “passionate coldness” to describe the hedonic treadmill of his contemporary couple: a distanced third person in conditional-punctuated habitual. Without consulting either book, it would be impossible to determine which one had said, “Their real lives were elsewhere, in a near or distant future also full of menace, but of a more subtle, less straightforward kind: traps you could not touch, spellbound webs.”[2] There is little that differentiates between Anna and Tom’s obsession with social media images, which make for the second half of their “double life,” and the cinematic images that reign tyrant over Sylvie and Jérôme.

Yet, despite the fact that Perfection might appear to readers as a vacuous remake, particularly in a time of cultural nostalgia and fading sui generis creation, most critics have argued that it isn’t.

Why?

Perec’s debut was coterminous with his time; he began writing his story of the ’60s in 1962, after abandoning his work as a market researcher, which had led him into a depressive crisis. Latronico’s work is cushioned by a sense of retrospect: a near-past nostalgia that seems increasingly typical of millennial novels in their documentation of accelerating metropolitan gentrification, the pandemic of social media, and the rise of podcasting as a cultural form (Latronico writes: “Their sudden inability to access a version of their past unfiltered by nostalgia, will be their understanding of nostalgia”). Unlike some of his contemporaries, Latronico uses this narrow distance to his advantage, and he writes with a subtle criticality suffused with empathy and humor that more readily invites identification with his protagonists, compared with Perec’s.

But the finer, more distinctive differentiation in Perfection is that Latronico subtly inflects Anna and Tom’s story with a globalism that has compounded in the decades since de Gaulle’s rise. The following quote—a break from Latronico’s typical simple single-clause declaratives—encapsulates the global network engaged instantaneously by renting their home online: “…plus the fee to cover the Ukrainian cleaner, paid through a French gig economy company that files its taxes in Ireland; plus the commission for the online hosting platform, with offices in California but tax-registered in the Netherlands; plus another cut for the online payments system, which has its headquarters in Seattle but runs its European subsidiary out of Luxembourg; plus the city tax imposed by Berlin.”

Unlike Sylvie and Jérôme, Anna and Tom are able to acquire most of what they seek by capitalizing on globalism’s exploitative cost efficiencies. Of course, they are no more emotionally fulfilled; but by allowing his protagonists to reach their desired endpoint—the villa that looks just like the pictures— Latronico is able to end his story with a more redemptive bend, one slightly more suggestive of the possibility for change.

Perfection’s more interesting point, one that Latronico cites as the anchor for his book, is the question of “how the hierarchy of languages shifting towards English is impacting what non-native readers expect, and what writers feel allowed to write.” It is a question that has famously preoccupied the Nobel laureate J. M. Coetzee for the bulk of his career, and one of increasing general cultural interest, receiving book length treatments, roundtable dispatches in cultural magazines, and even interactive walk-throughs in the New York Times (by Latronico’s brilliant translator, Sophie Hughes, who imports Perfection’s placid disaffection into English with the same distinctive grace as Fernanda Melchor’s violent, maximalist modern mythologies).

Yet, despite the relevance of Latronico’s interest and the willing audience for such an investigation, it is difficult not to feel like Latronico’s ambition is hampered by the structural framework he has inherited from Perec; that his thematic anchor is drowned in the slim novel’s ocean of descriptive detail; and that he would have been better off expanding the structure of Things rather than abiding by it so strictly.

The fact that history is relegated to the periphery of both stories is essential to their criticisms; the fact that Latronico identified the agility of Perec’s original form is a credit to his wit, and the fact that he finished and published the novel—a task he reflected on as feeling frivolous at times—is a credit to his grit. However, the detailed descriptions that compose the bulk of Latronico’s text are so predominant that they largely overshadow the finer points about globalism (particularly, linguistic colonization) that elevate Latronico’s Perfection to more than a remake.

Perfection, then, shares much with Menard’s Quixote. It is a literary adaptation disguised as a remake whose conceptual renovations justify its existence, one that is well constructed, and entertaining to read. Nevertheless, Perfection remains a book that is ultimately too tacit to extend beyond the shadow drawn by its original, an action that is imperative to the ‘newness’ of the novelistic form.

[1] The concept of remade or adapted art is most popularly associated with film, whose history of remakes and adaptations predates Borges’s writing of “Menard,” but whose prominence reached a cultural fever pitch in America at the turn of the millennium due to a confluence of factors—chief among them the economic cataclysm caused by a bursting dot-com bubble and 9/11—that pushed Hollywood studios to hedge the notorious unpredictability of box office returns by making “‘safer bets’” on that all-too familiar ‘IP.’ The result has been an endless stream of refactored work, and while some film scholars, like Daniel Varndell, have argued that an intertextual view of this cultural repetition can be important for connecting to a sense of collective social memory and historical insight, others have rightly decried the volume and consequent quality of remade films as a sign both of creative cowardice and of a culture drunk on ill-advised and ill-informed nostalgia (a particularly important point amid the recent rise and cultural dominance of reactionary politics).

Remakes are generally viewed with more straightforward disregard; to take two well-known examples, Gus Van Sant’s shot-for-shot reproduction of Psycho and Michael Haneke’s shot-for-shot English language reproduction of his German-language Funny Games, which were both universally panned.

Adaptations, on the other hand, tend to be viewed more complexly, and are even favored by the Hollywood Award Industrial Complex—think about all those formulaic musician biopics and adapted political biographies. Interformal adaptations that translate literary works into films have a rich, complex history that are less relevant to developing a paradigm for literary remakes. What is more useful is considering the intraformal adaptations that appropriate the name and ethos of existing films while varying in structural detail.

Take, for instance, the 2024 Amazon remake of Roadhouse, a cult classic adapted with an $85 million budget and released direct to streaming; an apparent “‘star-making’” turn for former UFC fighter and current White House mouthpiece Conor McGregor ( found liable for rape in Ireland in November of last year), in a film that inherits only the barbaric vigilantism of its forebearer, absent its same dilemmas of conscience and in CGI-choreographed form. Amazon recently announced that their Roadhouse has a sequel in the works. It seems that even the best case for an intraformal adaptation, such as Martin Scorsese’s international adaptation of Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s Infernal Affairs into The Departed, is for the adaptation to rise to the level of its original—a position it can never supplant, lest a viewer be unfamiliar with its influence, given the heredity of its creative force.

[2] The implications of English’s linguistic hegemony is in many ways core to Latronico’s Perfection. I have read Perec’s Things in French and in English as translated by David Bellos, whereas I have read Perfection only in English as translated by Sophie Hughes but not in the original Italian. It is unclear whether Latronico read Perec’s version in its original language or whether Hughes consulted Bellos’s interpretation of Perec’s French original. This is all to acknowledge that, like the couples in either novel, I am interpreting the essence of both of these works—their texture, feeling, and holistic style—in an inherently thwarted form (albeit one that Hughes and Bellos do justice by) that is one remove from its reality.

Conor Truax is a Canadian writer who has written for The Times Literary Supplement, BOMB Magazine, Spike Art Magazine, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Drift, and others. He interviews filmmakers for In Review Online, and is a recipient of the Giancarlo DiTrapano Foundation for Literature and the Arts’ Spring 2025 Residency.

More Reviews