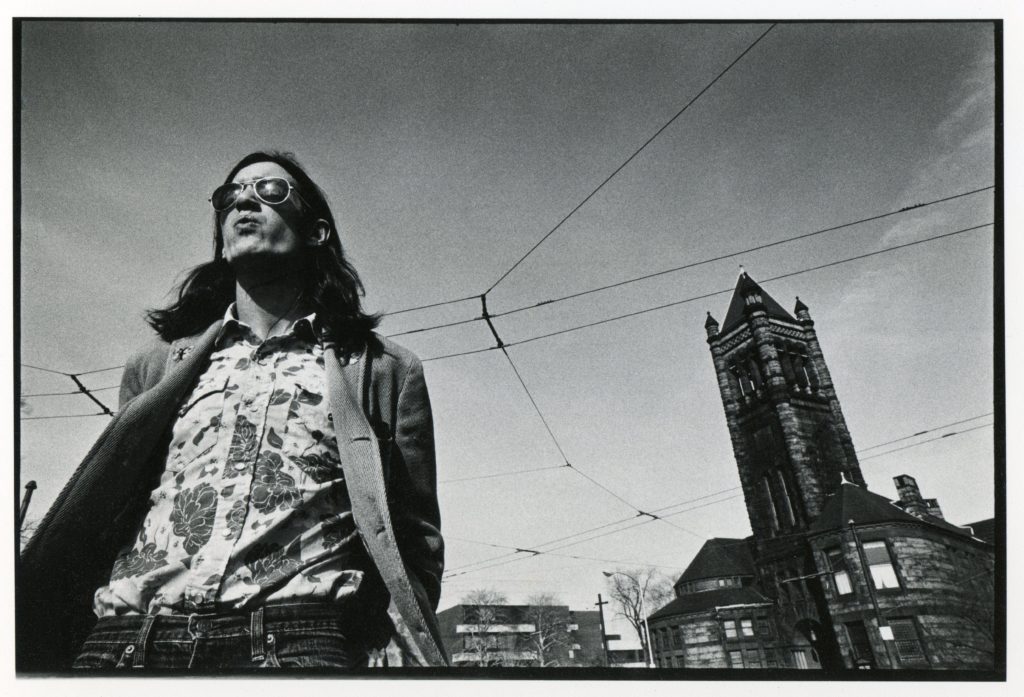

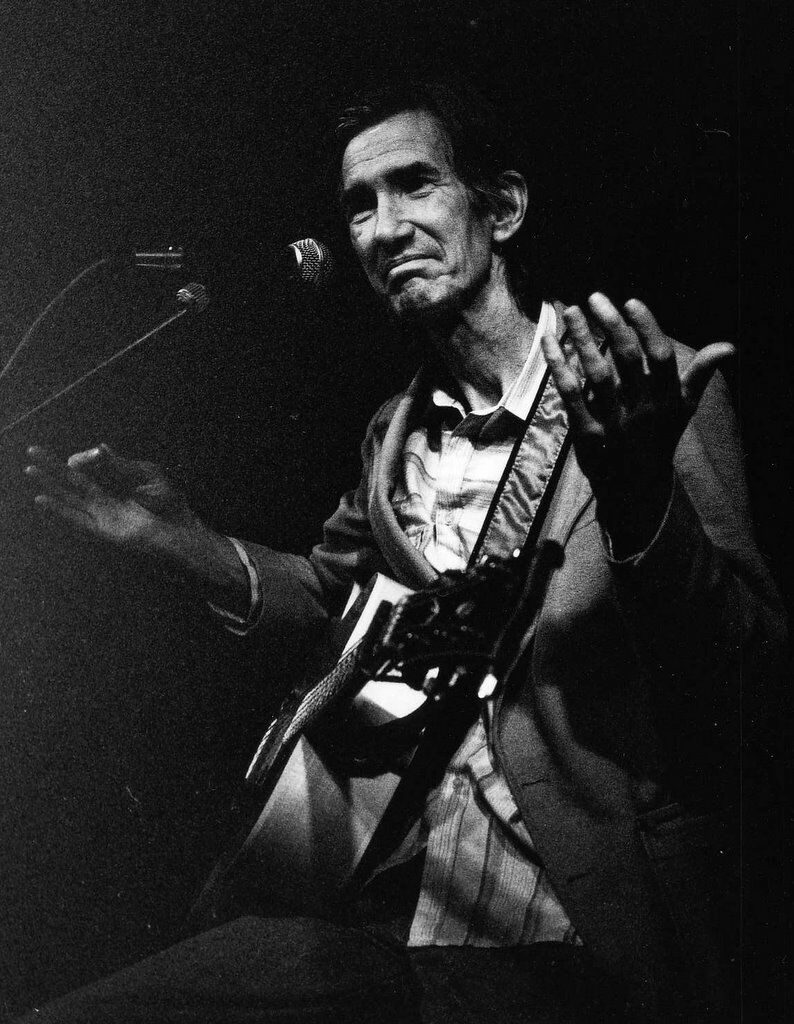

T oday would have marked the seventy-fifth birthday of country music outlaw Townes Van Zandt. To honor the occasion, TVZ Records and Fat Possum have issued a collection of unreleased recordings from 1973. Sky Blue features early versions of classics like “Pancho and Lefty” and “Rex’s Blues,” but the real news here is a pair of never-before-heard songs, “Sky Blue” and “All I Need.” We reached out to some of our favorite writers and asked them what they thought. You can read their comments below.

“With that unmistakable drop in octave tailing off the line, Townes’ voice swings like a sledgehammer against the human heart. I’ve spent many a night letting his words pour me empty. Thank God we now have two more tunes to cry to.”

—David Joy, author of Where All Light Tends To Go, The Weight Of This World, and The Line That Held Us

“I have always marveled at the way a Townes Van Zandt melody played in a major key can nevertheless sound minor. ‘To Live Is To Fly’ is a good example. ‘Colorado Girl’ is another. He can also move unpredictably from one minor chord to another, deeper-down minor chord, as if he’s plumbing an emotional reality unavailable to most of us. Van Zandt’s ability to shape and turn a melody gives his songs a surprisingly formal quality, as if the mood is intensified the more it is guided by musical structure, and by driving the mood to greater intensity, it is released. ‘Flyin’ Shoes’ comes to mind. I’m also reminded of an opening line by Emily Dickinson: ‘After great pain, a formal feeling comes.’ Dickinson also comes to mind for sharing a similar emotional terrain—heartbreak, despair, oblivion, transcendence.

“These qualities are especially present in two songs on this poignant new album, ‘All I Need’ and ‘Sky Blue.’ As I hear these songs, that tension between minor and major seems to be at work in both. In ‘All I Need,’ I hear the sung melody in a sort of major key, whereas the guitar steps down almost but not completely to a minor note in the third line of the verse. ‘Sky Blue’ is almost the reverse arrangement: the guitar is heavily minor, but the sung melody rises up from it toward the brighter light of the major notes, also in the third line of the verse. Although I’m not a trained musician, I can hear the musical structure of these songs, and, in terms of musical design, these songs sound like mirror opposites of each other. I think I’m observing form, at least what I’d call form in the realm of poetry—how shaping the sound through arrangement and pattern reveals a reality, an underworld, perhaps, that can be felt but not wholly articulated. This is the magic of art, its transport.

“The musical structure is one thing, but the lyrics have a similar mystery, and here I’m on firmer ground. I know of no other songwriter who practices the craft of poetry as Townes Van Zandt did. His verses are as careful as any stanza in poetry, and his arresting use of rhyme and also his play with language cause me to experience his songs not only as music, but also as literary expressions. Here are the final words of each verse in ‘All I Need’: down, home, own, load, and rain. The pattern is psychologically logical and persuasive. The verses move from registering a melancholy mood, to truth offered by friends, to the fickle nature of love, on to the deeply moving third verse in which the singer looks into his baby’s eyes and wonders, ‘Will his life be like mine?’ That line is fully loaded. It’s not a sentimental wonder; it’s a real, underlying worry, a moment of clear awareness shining out of the depths of the song. ‘All I need,’ the verse concludes, ‘is a way to take his load,’ the utter responsibility of love any parent faces when gazing into the eyes of a child.

“The emotional freight of personal despair and the responsibility of love find harmony in the rich final verse:

Aw, when good times

come fallin’ over me,

breath turns to melody.

All I need is gonna fall away like rain.

Here we see a gesture common in many Van Zandt lyrics, a turn to nature, even the apparently simple nature of rain. As I’ve listened to many Van Zandt songs recently, I’m struck by how often he steps back from the personal circumstance to bring in the sky, the wind, the sun, water, light, dark. ‘Breath turns to melody,’ he says, suggesting a transformation of the ordinary into art. The turn to nature also proves the human imagination, for all its darkness, is clarified when it returns to nature. By stepping back to nature, Van Zandt finds the broadest possible perspective, something universal and timeless that simply folds human experience into its silent reality. Is this a way out? Or is it simply the truth? I like to think it’s the latter. I can’t think of another songwriter who returns to nature with such eloquence and wisdom. It’s an ancient move in poetry.

“Whereas ‘good times / come fallin’ over me’ in ‘All I Need,’ the ‘blues keep fallin’ down on me’ in ‘Sky Blue.’ There’s a small but potent difference between the two adverbs. Falling over is generous, an outright gift. Falling down, on the other hand, is oppressive. The most poetic lines in ‘Sky Blue’ go like this: ‘to me livin’s to be laughin’ / in satisfaction’s face.’ This is poetry on the order of Robert Frost; the poetic devices are packed so tightly into such a small allocation of time and phrase. There is play between ‘to me’ and ‘to be,’ that is both sonic and grammatical. Laughin’ and livin’ are nicely alliterative. Then there’s the sonic current of the dense use of short a sounds in laughin’ and satisfaction, resolving with the long a sound in face. But the personification of satisfaction—giving this abstraction a face—turns the melancholy of the song into an expression that belongs to the world and therefore escapes the merely personal. This is the sort of hope any of us would have, an eternal hope that we may at last escape the darkest features of the human condition. And that makes the last two verses of this song all the more powerful. In the third verse, Van Zandt says, ‘Wish I was a settin’ sun,’ again making a turn to nature. Once in that state, the singer himself will assume the qualities of the sun on a mountainside: ‘feelin’ golden, burnin’ crimson.’ That’s how he’ll enter the dark. In the final verse, he tells how he’ll manage the dark, as a moon to ‘float the blackest skies.’ In that state he’ll assume the transcendent qualities of the moon, ‘being silent, being silver.’ And that’s how he’ll enter the light.”

—Maurice Manning, author of six books of poetry and a seventh, Railsplitter, due in the fall

“Like his hero, Guy Clark, Van Zandt had a way of capturing Texas—which is an impossible task—yet they did it somehow. The high-dry lonesome, the sweeping plains, the plenty masquerading as spareness; at once humble and grand. A sweet contradiction. A breath of fresh air. Hearing these songs feels like a resurrection.”

“Like his hero, Guy Clark, Van Zandt had a way of capturing Texas—which is an impossible task—yet they did it somehow. The high-dry lonesome, the sweeping plains, the plenty masquerading as spareness; at once humble and grand. A sweet contradiction. A breath of fresh air. Hearing these songs feels like a resurrection.”

—Randall Kenan, author of A Visitation of Spirits, Let the Dead Bury Their Dead, and the upcoming If I Had Two Wings

“There ain’t nothing wrong with ‘All I Need.’ Nothing at all. It’s Townes on my favorite themes: freedom and chains, the good kinds and the bad ones, and the impossibility of getting out them. I’m down with that. It’s what I want from Townes. That’s why Townes is one of my favorite songwriters: he won’t bullshit you about life. Except then we get to the end of ‘All I Need,’ and Townes reverses course to let you know there is one way out: singing. I don’t believe that. And I don’t believe Townes ever did. Maybe I’m wrong, but there’s nothing in his own life that’d lead anybody to that conclusion.

“There ain’t nothing wrong with ‘All I Need.’ Nothing at all. It’s Townes on my favorite themes: freedom and chains, the good kinds and the bad ones, and the impossibility of getting out them. I’m down with that. It’s what I want from Townes. That’s why Townes is one of my favorite songwriters: he won’t bullshit you about life. Except then we get to the end of ‘All I Need,’ and Townes reverses course to let you know there is one way out: singing. I don’t believe that. And I don’t believe Townes ever did. Maybe I’m wrong, but there’s nothing in his own life that’d lead anybody to that conclusion.

“But ‘Sky Blue’ is something else. I’ll take my Townes songs about the blues. There ain’t no getting out of the chains here. You can sing, sure, but it’ll be a sad song and won’t do shit to break any kind of chains.”

—Benjamin Whitmer, author of Cry Father and Pike and coauthor (with Charlie Louvin) of Satan is Real

“I always think the closest literary companion to Townes is Raymond Carver. There is consequence in what is stated and sung, but the menace and the meaning and the true artistry is all in what’s left out. Townes is a brutal editor of the human experience. ‘No good reason / to be living.’ Not for him, anyway. ‘Wish I was a setting sun / On a rocky mountain side.’ Well, who doesn’t, fucker? I know you know you are missed. Couldn’t you have settled for less, just this once?”

—Elizabeth Nelson, television writer, singer-songwriter in the garage-punk band The Paranoid Style, and regular contributor to the Oxford American, The Ringer, and Lawyers, Guns & Money

“Our modernity makes Townes Van Zandt’s voice available any second of any day. With the swipe of a finger or an incantation spoken to empty air, we summon him: John Townes, Come forth. But when these two songs never heard before—‘Sky Blue’ and ‘All I Need,’ recorded in 1973—filled my ears for the first time, I had a moment of fresh discovery, a break from the traditional, definitive catalog I’ve listened to most of my years. A cold February morning on the porch, a breeze startles the wind chime’s sail, the striker against the tubes. But the tubes’ once-hollows, now full with dry mud, crab spider husks, and dirt daubers’ eggs, bump together in muted song. This is Townes Van Zandt’s voice to me. Always has been. These new songs resurrect, if only for a few lean minutes, the body and voice—a life—once brimming with wildness, peril, and disease in always-midnight weather.”

—Elijah Burrell, author of the poetry collections TROUBLER and The Skin of the River

“TVZ, he’s my patron saint and I am his azure child. He bit his fingernail off and he threw it off. Now that’s where I come from. Spindletree bowing from crack in 7eleven tarmac. Come eleven.

“TVZ, he’s my patron saint and I am his azure child. He bit his fingernail off and he threw it off. Now that’s where I come from. Spindletree bowing from crack in 7eleven tarmac. Come eleven.

“Solemn as stone. Wild as wind worn to passion fires. Stones in ones you keep yourself beat any firework you might muster, buster. Mustard in her jeans. You can hear the oak palm the acorn. Can hear the rags quilting. Everything from ‘Flying Shoes’ to ‘You Are Not Needed Now’ to ‘Heavenly House Boat’ to ‘Greensboro Woman.’ Their threads crisscross these. Those songbreaths warming these to the temperature of a familiar hand.

“But Townes never was Townes in the studio—tho this beauty rings closer than anything to his actual stoicmanicpeakvale way. Can you hear him holding his face in studios. Can hear him trying to sound Townesy. So the felted words come like green velvet elbowpatches backed into old cypresses themselves shawled and webcobbed in Spanish moss. Face petrified.

“Follow the circle down he’s almost singing. Like a summer Thursday he’s almost singin. My heart laid on the ground he’s almost singing. High and low and in between he’s almost singing. To live is to fly he’s almost singing. Bottom low. A Song For, almost. The Hole for certain for sure. Buckskin sauce.

“A poet like this he’s a weather. Keeps a weathereye in. Mariner bites his skyblue own skin and radios in specter ships spare. Doom zoom. Gonna gamble for ya. You can hear here every song before and after as if herons lowerin over the river and now and soon to muscle up the mesquite the mosquito needle the brush the dusk. And you can hear it all exploded by tnt of self sent blue high set to settling. Always in Townes the sky the sky is falling. Playin chickencricket with sun then moon. Or the two clasped in exquisite and horrid broachbream while welcomin that, with wine, with guitars.

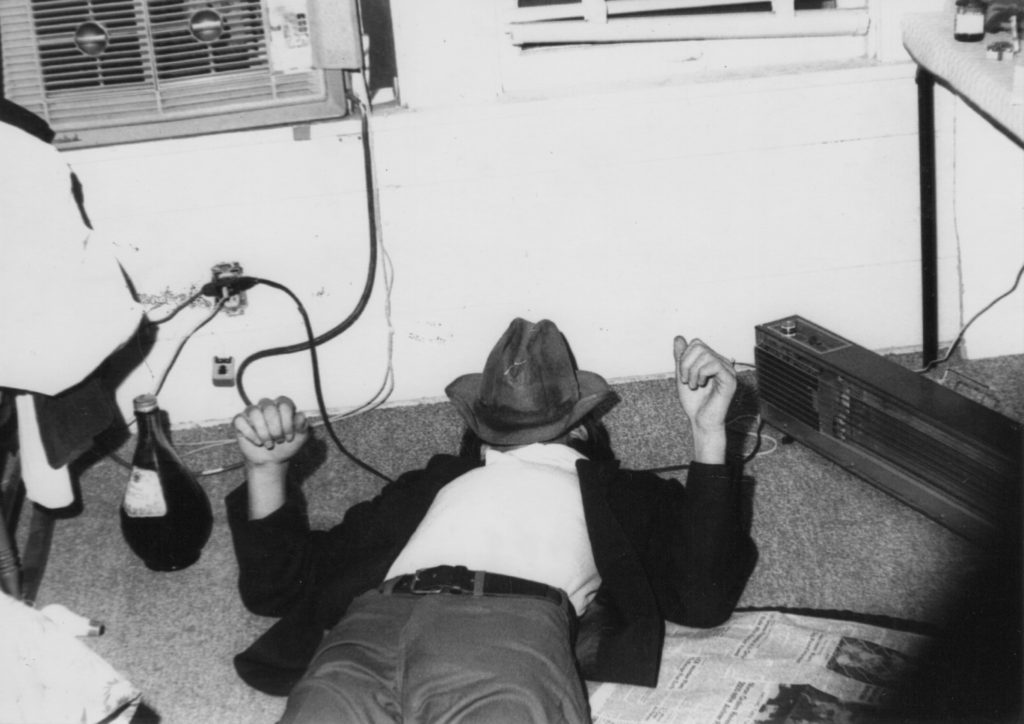

“Townes was Townes on the road where he was sandy prophet always. Thin so soon and with animal-never-meant-for-humanfeedin eyes. Full only in the hair. And often despairing on down to stone. Everyone has their story about a brush with his leaden parsimony while he hovered over a masonjar of brown goodbye. Mostly he said the same damn thing: two kinds of music the blues and zipadeedoodaa.

“Once she told me He bit my breast square on the nipple and I told him No one does that that’s not mine. So to give her a handle on himself he drew her this cactus. She showed me that pencil sketching like she was showing me the eyeteeth of her soul. Memory of Roadsongs’ thinset stalwart desert loll.

“The songs on the road and of the road and of the mountain and of the river, at his finest there there there there, seemed wrenched from him. As if he were a great vinegar flag the unseen and furious beauties turned and turned into revoluted cyclone still, the songs spilling there below, last taste quenchings those. Yes any floorwood you’ve ever seen shines, strange designs, Nothin moccasin skinnin. Skinny dew. There there and

for always he was just trying to go as he came. Back to this life he grins, the later visegripplucked goldtooth glinting like vitamin urine while sandwiched Rex pumps bb’s into beyond. Keats about how the drunked poem is the leopard and the drunket poet in wobblewheel carriage gets tugged sideways on.

“Poet Townes there’s something sad in knowing leoparded most of his gemchrome in lightning fashion before and soon after these Sky Blues and then just sort of hung on in thru the brackish backstreet hills, sideways. The road squeezed him. And trying everything 333 times squeezed him. By the wrists. He wrote maybe 12 more etched-to-mansion skybursts after ’73. Mainly he hung on to

the road the blackout undream. Or road spoiled sweeter: vinyl groove. Lil died of a broken heart. And maybe there’s a hybrid Loop flock still, in the bodega trashbag trees of NYC, the trashbags like great sharkjaws releasing.

“I had the poles in my life. Saw Townes in ’95 in London, sold out Chapel show and Townes rockcandy sold in the back. Now did I wear that No Deeper Blue tshirt until it fell to pieces. Until there was but one oval scrap over half one nipple. Yes. He played over three hours. Shook so hard from a new sobriety a pick leapt like magic from his frailin fingers and I fell on it, fell on like dog mousing hayrick mice. Said breathless to no-one I’ll carry this always: Xanadu fruit peel; Basho tear in a vial in a pocket. But I lost that. Like everything. And in Madison in ’96&3/4 after a Badgers football game, so sooner to his death day, in Townes time, the when he always said he’d go, the when Hank had gone, on Jan 1, and on that night in Madtown he was already in the Virginias, froze in the backseat of his heart. On that night while fat Badgers fans talked over him beefing beers into their brandyred faces he was the kind of drunk that can’t push down the string against the fret. Once I remember he yelled out, Hey, ddd’y’all win? Until gave up and tore into a meandertale about when he was last in Europe and how he’d thanked folks then promptly like a cartoon coyote fell off the high high stage and had recognized he was fallin in festival Germany and had turned midair for to protect his guitar. Might have been Blaze’s. Bam. Crk. On his back. Townes’ go-to sound for when something sudden happens. Crk. Hank too fell on his back–kirk–when drunk and hunting with his cousins with whom he first learned to fire that water and his back hurt like the lightnin of heaven ever after unless more. Jan 1. Crk.

“Like I say around more-more Townes the sky always is falling. And here you have him still rising to meet it, bleed it, need it. Take great care with this isn’t some old artifact or curio. The hot tea new again in the poetsculptor’s wide hand. The sweet slow hip of the Rockies fixing to be turning radiant from the shore from the stone to the sky. And I hope to see again one day. Wide-eyed. Woandering.”

—Abraham Smith, author of five poetry collections, most recently Destruction of Man, and co-editor of Hick Poetics, an anthology of contemporary rural American poetry and related essays

“Despite a well-heeled upbringing in one of the Lone Star State’s richest families, Van Zandt managed to craft songs of rambling and countrified lonesome that both buoy and bruise. His songs feel as bone-marrow true as those penned by less privileged geniuses such as Hank Williams or Keith Whitley. Yet, within these two previously unreleased tracks, one hears what has always separated him from the run-of-the-mill troubadours, those mockers of truth and beauty. It is akin to what the poet Robinson Jeffers christened ‘inhumanism’: a rejection of the frailty of flesh and the fickleness of desire that allows one to take up the cutting stone of language itself and so be willing to signify in song that which cannot be named. It is well enough to sing of the sky, or the rain, and not see a metaphor for the follies of man. But when one hears Townes Van Zandt at his best, one listens to an indwelling mystery that harbors no thought of man but sends forth praises for God. And as the old bluegrass tune would have it, the mystery ‘rings like silver and shines like gold.’”

—Alex Taylor, author of The Name of the Nearest River, The Marble Orchard, and the forthcoming novel, Blood Speeds the Traveler

“This is exactly what you’d expect from Townes—the aching voice full of longing and regret, tempered by the notion that the sun will rise again, somehow, someway. These songs possess the grit and beauty that make his world unique.”

—Michael Farris Smith, author of The Fighter and Desperation Road

“In ‘All I Need,’ Townes sings, ‘My chains keep playing tricks on me, / and all I need is a place to lay ’em down.’ It’s one of those lines that you feel like you know before you hear it, and it speaks to his great magic as a songwriter. ‘All I Need’ is sad and searching; it duplicates, like the best of his work, a certain kind of melancholy that lives in so many of us. It’s the sound of being lost and searching for a center. The same goes for the stunning ‘Sky Blue,’ where he sings: ‘I wish I was a snow-white moon. / I’d float the blackest skies, / being silent, being silver / till the break of day.’ These songs beat like hearts, showing us Townes at his vulnerable best.”

—William Boyle, author of Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, and A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself

“The closest I can get to describing the way these songs break upon me is to say I feel like I am listening to a ghost freestyle. The songs angle my mind and heart in different directions, as if the vocals are going forward and the guitar track is cut in reverse. How did he do it? There’s no one else like him. You have to listen, have to give yourself up to it, like he says in ‘All I Need,’ until ‘breath turns to melody.’ Breath turns to melody. My God. It’s all I need to be grateful again. Thank you, Townes.”

—M.O. Walsh, author of the novel My Sunshine Away and the story collection The Prospect of Magic