The rotund, bearded figure standing on Threadgill’s cramped outdoor stage looked uncomfortable, his eyes warily scanning an audience keeping Austin weird by honoring the man who helped the city earn that distinction. But when Roky Erickson apprehensively stepped to the microphone and opened his mouth to sing, it was like a record needle settling into a well-worn groove. Even after years of mental instability and poor health, his voice—a serrated howl conveying apocalyptic peril and emotional vulnerability—was robust, spellbinding, and unmistakably Roky. He didn’t hit all the notes, but he managed most of them, with an authority earned across decades of close-quarters combat with his inner demons. The hometown crowd ate it up, and I knew I was lucky to be there.

Most music fans have a favorite artist that they never got a chance to see perform live before the passage of time eliminated the possibility. My list of such acts is mercifully small, and I am grateful Erickson is not on it. He died on May 31, 2019, leaving behind a body of work that is equal parts compelling and confounding, with long stretches of inactivity punctuated by intermittent flashes of brilliance. To have caught a glimpse of that brilliance on an Austin night in 2012 is something I will always cherish.

I miss him now, and I nearly missed him then. Most of that muggy Saturday was spent debating whether to leave my hotel, located just across the street from Threadgill’s West Riverside location, now sadly closed. The fact that I was willing to stay holed up in an extended-stay room with a dreary parking-lot view reveals a lot about my attitude after a decade of SXSW sojourns. It might seem odd for a music person to kvetch about attending a festival, but burnout is real. After several days packed with panels and performances, I was not keen to reenter the swelter. But something told me not to skip Threadgill’s Psychedelic Ice Cream Social—the annual event to benefit Erickson, who for decades struggled with the aftereffects of prolonged drug use and institutionalization. Even with the threat of rain, I had no good excuse to stay in. And I’m glad I didn’t.

Shows come and go, but the great ones tend to stand out in our memories. I can clearly picture Erickson belting out “Night of the Vampire” with technicolor dread nearly equal to that of the 1979 original. When the music stopped, however, he seemed distant and preoccupied, like he was trying to remember if he’d left the stove on. One of his bandmates stepped up to offer encouragement. “You’re doing great, Roky—only three more songs to go.” Erickson nodded almost imperceptibly as he banged out the opening chords of “You’re Gonna Miss Me”—a song originally recorded with the 13th Floor Elevators and released in 1966, heralding rock’s psychedelic era. As the band fell in, Erickson squinted at the audience and flashed a beatific smile. By that point, the sky could’ve unleashed a deluge and I’d have remained glued to the spot.

It was a true delight to witness one of rock music’s most powerfully idiosyncratic talents delivering a gritty set of indelible garage-psych anthems. Equally remarkable is how those songs hold up decades after they were first put to tape—a testament to their originality, but also their tunefulness. As a songwriter, Erickson was both visionary and economical, evoking the otherworldly with the poetic equivalent of a five-color crayon pack. Not many artists could turn a lyric like “Two headed dog, two headed dog / I’ve been working in the Kremlin with a two headed dog” into a euphonic earworm, but Erickson pulled it off. And he still managed to sell it as a sixty-five-year-old man performing at a glorified barbecue—a minor miracle given his personal history, which contained enough pathos for several lifetimes.

That history can make being a Roky Erickson fan feel like rubbernecking. By now his legend is informed as much by his personal struggles as his musical output, which, over four-plus decades, is admittedly spotty. The same might be said of Brian Wilson, whose delicate mental state is inseparable from his genius, and whose admirers—myself among them—are perhaps too familiar with the grimmer episodes in his biography. Wilson is still with us, but he recently canceled a summer tour due to resurgent emotional issues, underscoring the precariousness of his lifelong battle with mental illness. Musically worlds apart, Erickson and Wilson have their similarities, including LSD experiments that profoundly affected each man’s psyche, leading to cognitive instability and creative decline. That both artists managed to come back from the brink to perform the songs that helped transform music culture in the 1960s and beyond is remarkable. Seeing these troubled figures in concert can arouse a range of emotions, some of them uncomfortable. We celebrate the heroism of artists overcoming profound challenges to spread joy through music. At the same time, their fragility begets a twisted intimacy that is borderline inappropriate. When we glimpse our favorite musicians mumbling between songs or looking dazed, even terrified, it raises questions about our own participation. With artists like Roky Erickson and Brian Wilson, the line between triumph and trauma is not clearly demarcated.

Erickson appeared to be coping well enough at the show I attended. In fact, once he warmed up, it looked like he was having a good time. Or at the very least he seemed happy that others were having a good time. Erickson was, by all accounts, a gracious man with a big heart. He existed on an entirely different wavelength from most human beings, but as he progressed in his recovery, his eccentricities became better integrated with his affable personality and less threatening to his well-being. Some performers are generous by nature, and I’d posit that there is nothing more generous than playing songs composed on the precipice of catastrophic breakdown some forty years prior. That it took Erickson decades to be in a position to do so in no way diminishes the joy he conveyed through his talent, his inner radiance shining through the fog of mischance and malady.

In 2005, Erickson kicked off his comeback on the very same Threadgill stage—a performance that was no doubt poignant for those in attendance, and even more unlikely than the show I saw. It was Erickson’s first musical appearance since a shaky 1993 set at the Austin Music Awards, where he was worrisomely unwell, stumbling around the stage and muttering incoherently. Around that time, a new generation of artists were getting into his tunes, yet the man who helped invent psychedelia lived in squalor—hair matted, teeth rotting, with multiple televisions and radios blaring to drown out the voices in his head. Erickson did manage to deliver a new album in 1995, the folk-tinged All That May Do My Rhyme, released on Trance Syndicate Records, an independent label operated by Butthole Surfers drummer King Coffey. Erickson is in fine voice throughout, though many of the tracks were actually remixes of sessions recorded a decade earlier. The album earned scattered accolades, but as Erickson was in no position to perform live, it sat neglected on store shelves as its creator languished at home.

The best of Roky Erickson’s work occupies a rare space between inspiration and obsession. Despite profound mental and emotional impediments, Erickson possessed an unparalleled ability to channel his confusion and alienation into songs as invigorating as they are unsettling. Erickson was capable of conveying powerful emotion with just his voice and guitar, always sounding authentic whether on homemade cassette tapes or on the scattered studio recordings made for various producers and labels throughout his career. He can still make the hairs on the back of my neck stand at full attention, a fact confirmed by revisiting his catalog in preparation for this article. I love 1960s Roky, the R&B savant with a crooner’s heart and an undomesticated attitude. I love 1970s Roky, the horror-punk prophet whose blistering shriek could shake Lucifer. And I love comeback-era Roky, his honeyed voice offering plainspoken entreaties for deliverance alongside the ominous and macabre.

I initially became intrigued by Erickson as an indie record-store employee and aspiring musician in the 1990s. Actually, it was a compilation album from early in the decade that first hipped me to his songwriting. Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye: A Tribute to Roky Erickson arrived in 1990 and featured artists like R.E.M., The Jesus and Mary Chain, and ZZ Top covering choice Roky cuts. From there I worked my way back through his catalog, becoming especially fond of his 1981 album with the Aliens, The Evil One. Then came the 13th Floor Elevators—Erickson’s 1960s unit that was allegedly the first band to use the word “psychedelic” to describe their brand of kaleidoscopic garage rock. Though the Elevators’ music is hardly commercial by contemporary standards, the group managed to crack the national charts with their debut single, “You’re Gonna Miss Me”—a three-chord romp with deliriously warped vibes that sounds like the British Invasion band Them cavorting with garden gnomes. When the song later turned up in the movie High Fidelity, it confirmed my own tribal affiliation—this was music made by underground weirdos for underground weirdos.

Even before he joined an acid-gobbling garage rock band, Erickson had experience negotiating chaos as the oldest of five brothers in a family that was equal parts nurturing and volatile. Born Roger Kynard Erickson in Dallas on July 15, 1947, Erickson had an upbringing on the low end of Austin’s middle class. His father was a booze-binging architect; his mother an amateur singer and devout fundamentalist who supported her son’s musical talents, starting with piano lessons at age four. “My mom always encouraged everybody to sing,” Erickson recalled in his final interview. “She’d say, ‘If you’re not going to do anything constructive around the house, the least you could do is sing! Sing a happy song.’”

As a kid, Erickson loved comic books and horror movies, influences that, along with his mother’s penchant for fire and brimstone, would inform his songwriting through times halcyon and harrowing (mostly the latter). Musically, he was drawn to cornerstone rock ’n’ roll and R&B artists such as Buddy Holly, Little Richard, and James Brown, all of whom influenced his early work with local act the Spades. Dropping out of high school a month before graduation to pursue his musical dreams, Erickson recorded a primitive version of “You’re Gonna Miss Me”—which he penned at age fifteen—before an encounter with University of Texas psychology student Tommy Hall in 1965 led to the formation of the 13th Floor Elevators.

Erickson was the Elevators’ lead singer and guitarist, his frantic yelps and gritty licks colliding with Hall’s electric jug—an amplified version of the old bluegrass accompaniment that gave the Elevators their distinct sonic wobble. In addition to relentless jug huffing, Hall was also an LSD evangelist; like many of the era’s psychonauts, he was convinced of the drug’s potential to transform human consciousness. Hall encouraged—even demanded—that members of the band take acid before every show. Erickson embraced this mandate to his immediate and long-term detriment. Drummer John Ike Walton later recalled, “It got so bad Roky wouldn’t even sing. He would just sit there with his back to the audience and his amplifiers squealing.” For whatever reason, some people are able to ingest epic amounts of acid and emerge intact, while others suffer breakdowns they are lucky to recover from. For example, the Grateful Dead’s LSD experimentation only enriched their collective interplay, with no obvious cognitive degradation among individual members. Former Pink Floyd leader Syd Barrett, on the other hand, became an early acid casualty whose onstage aphasia was disturbingly similar to Erickson’s.

By early 1966, the Elevators were bona fide stars in Texas, with a promising national profile owing to a warm underground reception for their first record, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators—a groundbreaking effort that advanced an agenda of consciousness expansion at a time when most pop musicians had yet to smoke a joint. Key to the band’s impact was its singer and guitarist, whose salty croon and banshee wail were compellingly original. Former Warner Bros. executive Bill Bentley was effusive about Erickson’s talents. “He was the most electric performer I’ve ever seen, and that includes Hendrix,” Bentley recalled. “He was possessed, so vivid and mesmerizing. His voice was so sharp and cutting—sometimes he’d get lost in his screams.” Screams would soon soundtrack Erickson’s offstage existence as an inmate of Texas’s most notorious institutions. As forward scouts for the Summer of Love, however, Erickson and the Elevators enjoyed a glimmer of transcendental bliss before bad luck and worse choices ravaged their reality.

Dodging drug busts in their hometown, the Elevators took to the road, appearing on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand television show in 1966 and playing a series of well-received West Coast gigs that inspired Bay Area musicians to double down on psychedelia. Erickson’s condition was rapidly deteriorating, however—hard narcotics were soon added to his pharmacological repertoire, and he allegedly started wearing a bandanna so audiences wouldn’t see his third eye. By 1968, Erickson was a shadow of his formerly effervescent self, but he retained some awareness of his increasingly compromised state. “Get out bad spirit!” his friend Terry Moore recalls the singer screaming as he swallowed another fistful of acid.

The situation proceeded from dicey to disastrous. The following year, Erickson was busted for marijuana possession—allegedly a single joint—shortly after which the Elevators broke up. To avoid a protracted prison term, Erickson pleaded insanity, which led to his enduring several years of electroshock therapy and a barbarous Thorazine regimen that no doubt caused as much damage as the illicit drugs. After multiple escape attempts from the comparatively benign Austin State Hospital, he was transferred to the maximum security ward at Rusk State Hospital, where he formed an oldies band with hardened criminals called the Missing Links.

Erickson continued to compose during his institutionalization—a collection of his poems from that period, Openers, was published in the early 1970s, and his mother recorded some of his music during visits. These spare, haunted songs later appeared on the 1999 compilation Never Say Goodbye. Whether his mental health improved or worsened while at Rusk is a matter of debate. Either way, a federal judge in 1972 declared him fit for release. The music he made as a free man tells a different story. Erickson’s output in the ’70s took a turn toward the delusional, with phantasmagorical lyrics packed with B-horror references and paranoid ideation. “I am the doctor / I am the psychiatrist / To make sure they don’t think / That they’d hammer their minds out,” he crooned on the disturbingly revealing “Bloody Hammer.”

British journalist Nick Kent interviewed Erickson for NME in 1980, an article subsequently republished in Kent’s ghastly survey of rock star derangement, The Dark Stuff. Even alongside vexing interactions with the likes of Brian Wilson and Syd Barrett, Erickson’s entry stands out for the alarming degree of delusion on display. “The devil, see, he’s my friend,” Erickson told Kent. “Ah am his, uh, chosen one. Out of all the people in the world he came to me and said, ‘Roky, you are mah . . . human?’ ” The interview took place over two days during a brief UK jaunt to promote Erickson’s solo debut, Five Symbols. The singer was catatonic for most of the trip, but occasionally the mental clouds would clear—albeit briefly, and always after sunset. Even then, Erickson’s grasp on reality was tenuous. “See, them at the hospital, they tried to keep me in there, but they didn’t realize my power,” he said. “How could they?”

Despite his frayed condition, Erickson’s work at the time was powerful, if not maniacal. Upon release from Rusk, Erickson hooked up with legendary Austin musician Doug Sahm, who cajoled Erickson into the studio to record four tunes on a budget of one hundred dollars. Two of them, “Starry Eyes” (which Erickson claimed was sent from heaven by fellow Texan Buddy Holly) and “Red Temple Prayer (Two Headed Dog),” would become standouts of his songbook. Other classic cuts of this period include “Creature with the Atom Brain,” “I Walked with a Zombie,” and “Don’t Shake Me Lucifer”—all of which cemented Erickson’s reputation as the crown prince of graveyard rock. By the late 1970s, a new breed of artists embraced Roky as the real deal. Patti Smith said his work was “inspirational,” and the band Television was known to cover the Elevators’ “Fire Engine.” Peter Buck of R.E.M. called Erickson’s songs “concise and terrifying in their power.” And yet Erickson seemed incapable of capitalizing on his talent or notoriety. A series of bad deals and squandered opportunities left him nearly destitute, his mental and physical health worsening by the year. Still, he managed to get married and divorced twice, fathering three children along the way.

In the 1980s, Erickson rarely left the house, instead developing an obsession with correspondence, spending hours contemplating junk mail and writing manic letters to celebrities—living or otherwise. In 1989, he faced federal charges for stealing his neighbors’ mail. (Charges were dropped when it became clear that Erickson never actually opened any of it—he merely taped it to the walls for “safekeeping.”) During this time, he was looked after by his mother, who believed his mental afflictions were best addressed by prayer. As a result, Erickson’s state further deteriorated; at one point his teeth had rotted to the extent that an abscess nearly infected his brain. When journalist Kevin Curtin later inquired about the period, Erickson replied, “It wasn’t really a time. It was more of a change of concepts.”

Thankfully, more positive changes were imminent. Erickson’s youngest brother, Sumner, a musical prodigy who at the age of eighteen earned a spot playing tuba for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, can be credited with saving the singer’s life. In 2001, after a fraught court battle, Sumner was granted legal custody of his older brother. Erickson’s tangled business affairs were sorted out and his schizophrenia addressed with medication. This period of struggle and renewal is the focus of Keven McAlester’s heart-rending 2005 documentary You’re Gonna Miss Me, which was screened at SXSW the same year Erickson made his onstage comeback. (The film now appears to be out of print—a situation one hopes will soon be remedied.) “It’s just a real strange movie,” Erickson said. “But I enjoyed it.” Later that year he performed a full concert at the Austin City Limits Music Festival, backed by the Explosives and featuring longtime admirer Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top. According to an article by Margaret Moser in the Austin Chronicle, in 2005 Erickson also got his driver’s license, weaned himself off medication, and voted.

The 2000s and ’10s were a good time to be a Roky Erickson fan, and by all appearances, a more humane and inspired period for the artist. Enjoying greater emotional and financial stability, he made compelling music with a contemporary cast of characters drawn from the Austin music community. In interviews, Erickson was more cordial than catatonic, and seemed pleased—or at least amused—that his music still generated interest after all these years. In a 2010 conversation with sometime bandmate Will Sheff, Erickson remarked on what it was like to talk with journalists. “I enjoy it,” Erickson said. “I try to have pity on ’em and not be mean to ’em.” And he still loved his horror movies. “Sometimes I get a little unhappy if I don’t get to see ’em all,” Erickson said backstage at a 2009 concert. “But I know somewhere in my heart that it’d be all right that I didn’t.” Erickson spent more time on the road in the 2000s than at any previous point in his career, with first-ever gigs in New York City and Europe. “I just sing a lot, and scream a lot, and entertain or something like that,” he said of his expanded schedule.

Erickson’s solo bands were always rock solid, with the Aliens being the best of the pre-comeback bunch. When he came back to active duty, he had the good fortune of being backed by some of Austin’s finest indie acts, including Okkervil River and the Black Angels. On their own, these bands are quite different—the former is a sturdy Americana outfit unafraid to color outside the lines; the latter an enveloping psychedelic band that owes as much to the Velvet Underground as the 13th Floor Elevators. Both groups were terrific interpreters of the Roky repertoire, respectful of the contours and context of his work, yet representative of rock’s creative vanguard. Erickson typically rose to the occasion, no matter who was backing him up. He also seemed more accepting of attention, though it was clear that aspects of his identity had been sandblasted through years of suboptimal treatment, self-abuse, and neglect—benign or otherwise. No amount of agreeability could mask the fact that Erickson wasn’t all there. But in performance, at least, his presence was undeniable.

The same can be said about Erickson’s final album, True Love Cast Out All Evil, produced by Will Sheff and released on the ANTI label in 2010. Unlike other artists at the tail end of their careers, Erickson was the sole composer of all twelve songs on the record, though many had been written in years prior. A twangier affair than the garage-psych of the Elevators or the metallic punk of his ’70s and ’80s work, True Love Cast Out All Evil found Erickson in a ruminative mood, his yearning vocals set to soft-focus Americana more cozy than cosmic. Portions of the album could reasonably be called country-gospel—if Roky was once “the devil’s human,” that arrangement had been superseded by a higher authority. Erickson’s ghoulish obsessions were far less prevalent, his third eye now trained on salvation. That doesn’t mean the songs aren’t weird—Erickson couldn’t make a conventional record for all the ice cream in the world. With chugging guitars and Erikson’s sandpaper moan, “John Lawman” is closest in spirit to his previous work. The song has one verse, repeated three times: “I kill people all day long / I sing my song / Because I’m John Lawman.” Erickson manages to resolve the dichotomies of his faith in “Think of as One,” which comes across as more Buddhist than Christian. “You are you / She is she / He is he / I am me / Be you / We are all equal / Think of as are,” he sings in the song’s buoyant refrain.

Everyone loves a good redemption story, but some of them seem to be more a product of public relations than perseverance. Roky Erickson was authentic to the core, so it’s unsurprising that his story scans. At the end of the day, debating which artist’s fall was the most severe or who is most deserving of recovery is not only pointless, but perverse. Erickson was a real human being who at various points in his life suffered greatly. Despite this, he managed to give a tremendous amount of himself as an artist under conditions most would be incapable of enduring. It’s easy enough to see Erickson as a cautionary tale, one of gratuitous self-abuse and poor judgment. Of course, this outlook fails to account for the factors of his upbringing or the institutional injustices he experienced. There’s a heroic aspect to Erickson that I believe is big enough to contain all of the contradictions and idiosyncrasies present in his life and work. Underneath the horror movie tropes and antagonistic dualities is the simple radiance of a gentle soul. I’d like to think that this is a facet of the universal spirit referenced in Erickson’s final recordings—an all-forgiving, all-encompassing wellspring of creativity and compassion. Remember, the Evil One was actually an angel. It’s not so strange to think that Roky was, too. ![]()

Casey Rae is a cultural critic, professor, and music industry professional who lives in Washington, DC. His book William Burroughs and the Cult of Rock ’n’ Roll (University of Texas Press) was published in 2019.

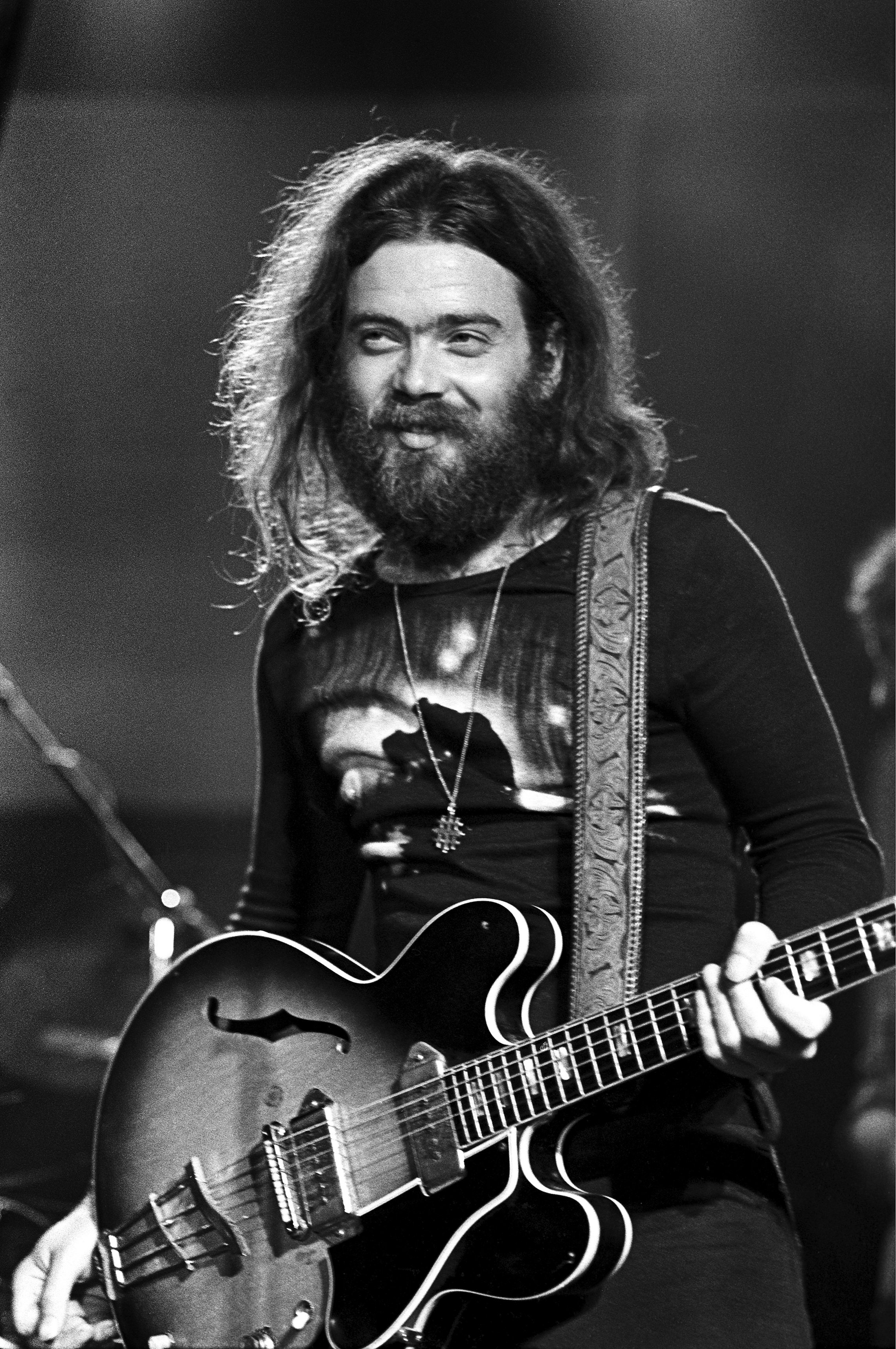

Photo: Scott Newton