A Cure for Loneliness

Reviews

By Drew Broussard

When I worked in theater, I overheard a literary agent giving a group of playwrights some advice that has stuck with me through the years. The playwrights had just come out of a new-work showcase, where they’d presented ten minutes from their in-progress scripts, and the agent said: “If you chose anything other than the very beginning of your play, the scene you chose should be the beginning of your play. Start with what’s most exciting to you and the audience will catch up.” It’s good advice, a particular kind of “kill your darlings,” and it came back to me about halfway through Charlee Dyroff’s Loneliness and Company, a novel with heart and good intentions that is nevertheless unsure of what it actually wants to be.

The novel follows Lee, a brilliant research analyst who expected to land a high-flying job at a major corporation but unexpectedly ends up in a podunk gig at a company in a hollowed-out New York City. She discovers that her team is meant to be training an AI called Vicky as a government-funded weapon against a growing epidemic of loneliness. As she works, she begins to interrogate her own self-sufficiency and the true cost of our technological lives.

We’re meant to understand that the novel is taking place in The Future, although how far in the future is an unresolved question. Dyroff leans on the shorthand of dystopia to suggest that we are some ways off from the present. Generic proper nouns pepper the novel like so many mushrooms after summer rains (the Program, the Government, the Emotional Index, devices just called Screens, a dating app just called Dating), and there are vague references to climate disasters that have left the East Coast decimated and turned Midwestern cities into the hubs of art and commerce. We are also told, in a most unbelievable and confusing leap in logic, that the idea of loneliness—the very word itself!—was erased from society several decades prior. What a tragedy, then, to learn that every recording of Elbow’s spectacular “The Loneliness of a Tower Crane Driver” or every copy of Olivia Lang’s seminal The Lonely City must have been destroyed at some point, in some kind of well-meaning but short-sighted purge.

I’m being a little harsh, and I suppose there is room to argue that I should just do a better job at suspending my disbelief, but the plot of the novel hinges on an idea that collapses any time I so much as look at it sideways. People are still experiencing loneliness, but now they don’t have the words for it? And it turns out the government (sorry, the Government) has been aware of this all along and thought that a virtual friend would be a cheaper solution to the problem than investing in mental health support or community building? (To be fair, that last part does sound like something the government would do.)

Shaky world-building combined with a myopic main character whose only interest is in getting a better job do not make for tremendously compelling reading and I struggled to get traction with the book—but then, Lee comes home from a tough day at work (the existence of loneliness has just been revealed and it has thoroughly shaken her whole team) to find her roommate on a video happy hour with friends. She joins their conversation, ostensibly to take notes for the AI she’s training, but ends up agreeing to make a dating profile and start getting out and experiencing the world. All at once, the novel springs to life. Here, I thought, here is where things should begin.

Dyroff has an absolute blast writing Lee’s headlong dive into the messiness of a well-lived life, from a series of ridiculous dates and commensurate heartbreaks to trying new cuisine (“no interesting night starts with a salad,” Lee’s research tells her) to the glorious pain of recreational running. I could have spent twice as long in this phase of the novel, and I wondered as I was reading it whether Dyroff needed any of the contorted dystopian elements of the novel at all. At its best in this mode, the book aspires to the heights of Marie-Helene Bertino’s Beautyland, a novel whose unselfconscious delight in depicting the beautiful weirdness of the human experience through the curious and anthropological lens of its overly analytical main character represents a high-water mark for hopeful literature.

It is not much in the way of a spoiler to note that Loneliness and Company ends as you might expect, with a triumph of humanity over technology. The ticking bomb of the plot returns (more and more people are manifesting symptoms of the loneliness epidemic, although I would describe their symptoms—listlessness, ennui, suicidal ideation—as those of clinical depression rather than garden-variety loneliness), followed by the revelation that all of the other labs working on “cures” for loneliness have failed, a scene that reminded me of nothing so much as a similar scene in The Cabin in the Woods except with none of the underlying horror needed to support the characters’ intensity. Indeed, as the novel speeds toward its conclusion, characters start to act in increasingly ’90s-sitcom ways, prone to bombastic pronouncements and serendipitous interactions: one character announces a change of heart about their work by saying that “Vicky is on the cusp of working, and then what? A world where people connect with technology instead of each other? We already have that. I’d rather have a world of lonely people than a world of numb ones.” This, despite the fact that they’ve all apparently worked in tech for their whole adult lives.

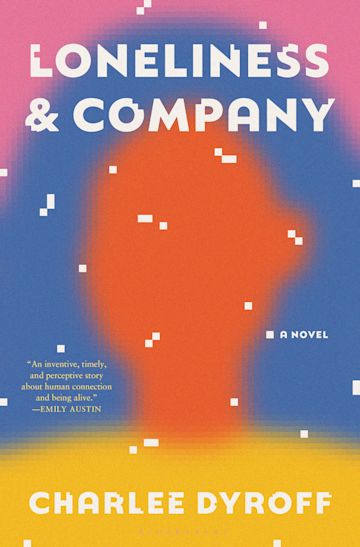

It’s all so obvious, and that’s not exactly a problem—if anything, I think the recent boom in romance novels and cozy genre fiction is a sign that readers are in fact hungry for warm-hearted reminders of the perils of technological over-reliance and the awkward charms of human interaction—except that, again, I found myself wondering about the why of it all. Dyroff has a gift for writing about the simple beauty of human connection and a clear, urgent desire to get us to look away from our devices and toward one another, but Loneliness and Company is as pixelated and buggy as its cover unintentionally suggests it will be, leaving its timely message lost in lines of bad code.

Drew Broussard is a writer, producer, and bookseller living in the Hudson Valley. His writing has appeared at Literary Hub, Tor Nightfire, Oh Reader, 3:AM Magazine, Unbound Worlds, and in friends’ mailboxes. He spent eight years on the artistic staff of The Public Theater and now produces podcasts with Literary Hub and events at The Golden Notebook bookstore in Woodstock, NY.

More Reviews