A Drug Story Is Never Just About Drugs | An Interview with Nick Rees Gardner

Interviews

By Gene Kwak

In June of the year of our Lord two thousand and twenty-four, I was blessed to come across an all-caps tweet from award-winning author Morgan Talty singing the praises of a book called Delinquents and Other Escape Attempts by Nick Rees Gardner. Talty called it “brilliant” and “begg[ed] everyone to buy this book.” The tweet wasn’t actually in all caps, it just seemed like it. I immediately reached out to Kevin Breen, the founder and executive editor of Madrona Books, the publisher of said brilliance, and he graciously sent it to me in a digital file. I specifically asked for a digital copy because I was leaving the next day for a writing residency in the wilds of Wyoming, where I promptly devoured the thing while staring at downpour-avoidant fawns, entirely too comfortable bull snakes, and dead roadside porcupines. Although Wyoming and Ohio are incredibly far apart geographically, we were staying near small towns (although even labeling them towns would be pushing it, more like hamlets) that abutted majestic mountains, which meant that their populations were a mix of never-left locals and outside high rollers who hoovered up all the available land. One town consisted of a single street with four bars and a wood-fired pizza place housed in an old mercantile building. So the class issues that Gardner grapples with in Delinquents felt pertinent during my residency read.

I remember one day, right after I’d gotten done devouring “Spit Backs,” a heart razer of a story about documentary filmmaking and friendships and disappearances all revolving around a recovery house, I just had to stare out of a window for an hour. True story: about two hours later a flock of wild turkeys tried to headbutt themselves in their own reflections in the very same back window. I didn’t have that physical of a reaction, but I understood that sometimes you just wanted to double-check that you’re alive. I immediately emailed Nick Rees Gardner for some answers.

Gene Kwak: In an interview with Madrona, you talked about how there was initially a massive novel draft that then got turned into Delinquents. Can you talk about the process of shifting that draft into the current version of the book? Was it completely restructured from the ground up?

Nick Rees Gardner: I still think about that novel draft a lot. Before the novel, I’d written a lot of short stories and poems, but I still wondered if I had what it took to be a real writer. When I finished that one-hundred-thousand-word draft, that was the evidence I needed that I could actually be a writer, could actually write books.

Nick Rees Gardner: I still think about that novel draft a lot. Before the novel, I’d written a lot of short stories and poems, but I still wondered if I had what it took to be a real writer. When I finished that one-hundred-thousand-word draft, that was the evidence I needed that I could actually be a writer, could actually write books.

Delinquents, the failed novel, was a story about two friends, one a heroin addict and the other recently recovered, who live together in a podunk Midwestern town. There were lots of DIY punk shows in that draft, lots of “urban exploration.” I was interested in the connections between people and place. I’d recently gotten out of rehab for opioids, and in a way that draft was teaching me how to enjoy the same things I once did, but this time without drugs.

Delinquents, the story collection, definitely shares a lot of those same themes. I wanted to track the use of buildings from their original intended use to their abandonment and then reuse by the unhoused, the urban explorers, etcetera. So, yeah, the story was completely restructured, but it’s about a lot of the same things.

In the novel, I called the town “Westinghouse, Ohio” because I didn’t want people drawing too many connections between the fictional town and my hometown of Mansfield, Ohio. But by the time I got around to writing the stories in Delinquents (the collection), I’d settled into Westinghouse. I’d used it in a couple other stories (that didn’t make the collection), and even my novella, Hurricane Trinity, though it doesn’t mention Westinghouse specifically, features characters from Westinghouse. The tentative title for the novel was Delinquents, and when I finished writing the stories that make up my collection, I felt like the title fit.

GK: Can you talk about the process of organizing and ordering the stories once you reimagined the book as “linked stories”? And why was it important to refer to it as “linked stories”? What do you think that does for the expectations of the readers? Or for you in thinking about it as a whole?

NRG: The structure actually hasn’t changed too much. Over the couple years I had the collection on submission, I bounced between the current nine stories and a version with eleven stories. But the extra stories had a different voice, even though they shared a locale and had overlapping characters. The novella, as may be expected, was the most difficult to place. So often the novella is the last piece in the book, but one of my professors, Lawrence Coates, mentioned the idea of adding a short piece after the novella as a “grace note.” I loved the idea. Like, a novella takes a bit more commitment to read. If it’s done right, the reader lingers on it for a while. But then, before they check out, move on to the next book, there’s this little energetic zinger at the end. A novella can be a slog. A “grace note” story is a relief, in a way.

In my Madrona Books interview, I talked a bit about how one press told me they “failed to see a through line” in the collection. Sometime after that rejection, I added the subtitle: And Other Escape Attempts. If editors were missing the connections, I wanted to spoon-feed it. Once Madrona picked up the book, my editor, Kevin Breen, suggested adding “linked” to the cover. I’m pretty ambivalent about that. It’s a marketing thing. But I imagine a reader might think of the collection as something bigger. I mean, novels outsell story collections all the time, so that one word, “Linked,” I think tells the reader that even though these are standalone stories, their connections will build something bigger. Critics call books “unputdownable” as if that makes it a better book. With short stories, you can put the book down every ten to twenty pages. So maybe that “linked” aspect gets the novel readers’ attention. Again, in my mind, it’s a marketing thing, and I appreciate working with a publisher who will add the words necessary to the title to get people to read my book.

Once I dug into editing with Kevin, I began to see other options to connect the stories. Each story is its own thing, powerful in its own way, but once you’ve finished the book, you get a sense not only of the town, the place, but also its mythology, its history, how these things shape a person. So you basically get to understand all the characters more deeply as you understand the place that connects them. In the final round of edits, I added a couple Easter eggs. In one scene in Captain Failure, Dunk walks into a bookstore and notices two other shoppers who are actually main characters in earlier stories. It’s fun to notice these things. You get to see how interconnected everything is. You get to see the same world from different perspectives and that’s kind of what literature is all about.

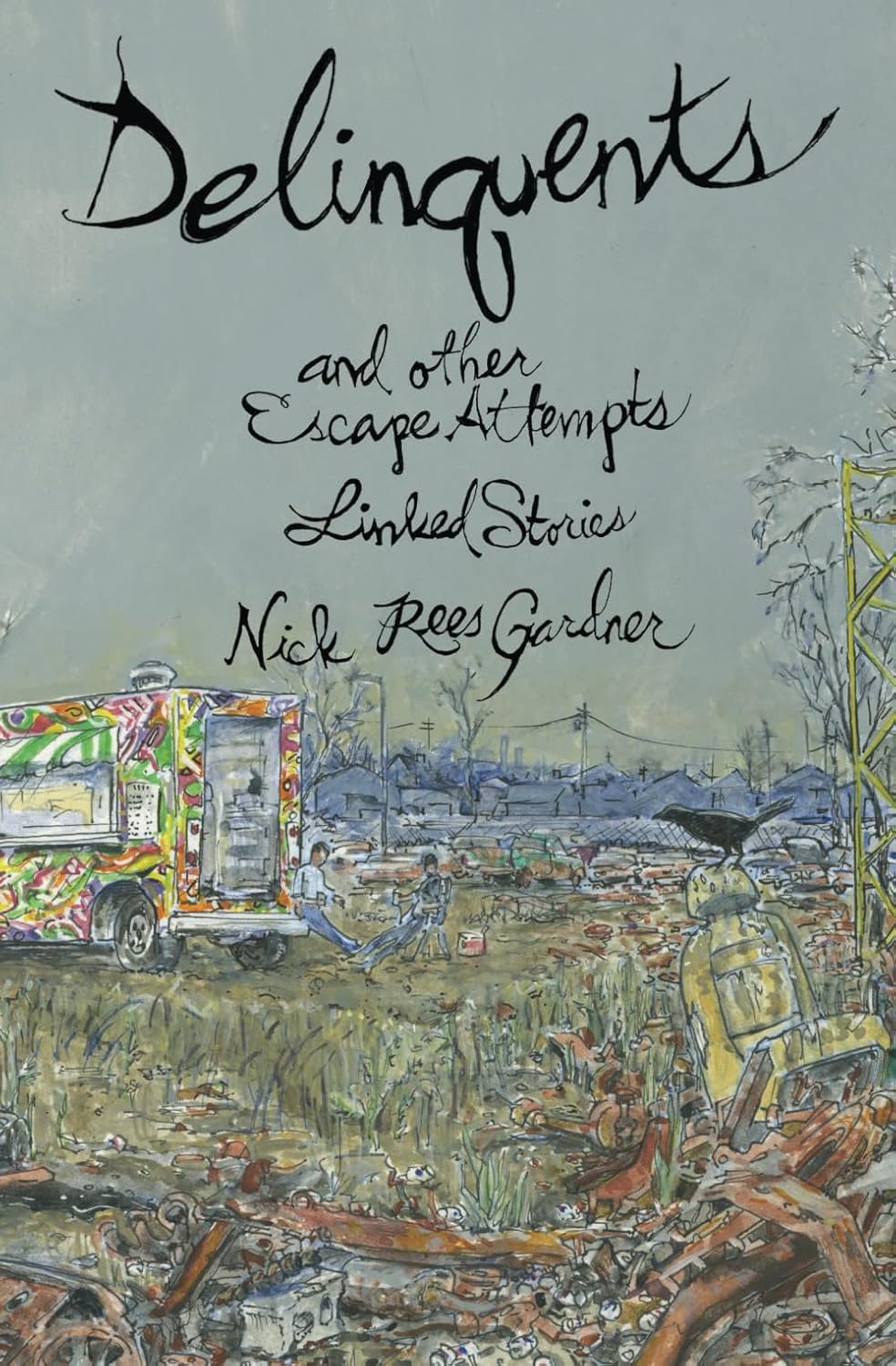

GK: Can you talk about the process in working with the artist who did the cover and the inside map? The artwork really matches the stories well. There’s a vibrancy among these muted colors. Really nailed a Midwestern sky.

NRG: Hell yeah! John Thrasher’s artwork made this book. The physical object of any book is really important to me. That’s one of the reasons I felt safe with Madrona to begin with; Kevin Breen has a good eye and his layout is spot-on. When a cover doesn’t line up right or just plain sucks, or if the pages are jam-packed with words and tiny margins, it really turns me off. I also knew from the time I first submitted Delinquents that it needed a map, and Kevin was very open to my ideas.

I used to hang out in John’s art room in college and I always admired his art, so he was the first person I asked. He was enthusiastic about the project. I think he read the book like two or three times and we exchanged a dozen or so drafts of the map. One funny thing: I asked him to add “The Drinks Bar,” a local watering hole mentioned in a few of my other Westinghouse stories, but which I apparently never mentioned in the current iteration of Delinquents. He caught that slip-up, among others.

After the map, John offered to draw the cover. We went through several versions over a couple months with both Kevin Breen and my partner (a book buyer at a local bookstore) adding comments. Originally, Kevin mocked up a couple cover designs that emphasized the more ludic nature of the stories, and when John jumped on board, his early sketches leaned toward dingy and dilapidated visions of the Rust Belt. Kevin’s sky was blue and John’s was dark gray. It took many, many drafts to come to the current coloration, before we landed on something that spoke to everyone’s understanding of the book. And I think that’s really the point. A book is a collaboration. It’s my ideas, my voice, but, as an editor, Kevin guided me to a translation that was easier to consume. And then the art is another translation. It’s awesome to see John’s penchant for graffiti and cartoons sprinkled into the cover, all these different personalities meshing. I mean, the cover is definitely John’s art, but it takes into account all four collaborators’ understanding of the book. I’m biased, but I think it’s perfect.

GK: And to piggyback off that question, can you talk a little about the creation of Westinghouse, Ohio? At what point did you know you needed to create your own “postage stamp of America” according to Faulkner? And what purpose did it serve for you?

NRG: I realized early on that I couldn’t set these stories in my actual hometown. There are too many logistical issues, not to mention I don’t want to piss off any locals, or worse, deal with fact-checkers. In many ways, Westinghouse is the version of Mansfield I experienced while I was using. I inhabited dingy spaces, even hung out with drug dealers in junkyards. So there are a lot of autobiographical experiences involved in the placemaking.

But Westinghouse became a lot more than a Mansfield proxy as I tried to weave the stories together. At one point, I sketched a crude map of all of these places, and I think that’s when Westinghouse really became a solid, real place. I learned about Westinghouse as I wrote, too. I’d write a scene in a bar and be thinking about that bar, wondering who else was in there. Was Dunk bartending? When my food truck workers park at the local brewery, do they run into Lissa from “Lifers, Locals, Hangers-On”? There’s something cool and fun about diving headlong into a character’s life and then looking up and seeing another character in the periphery. In short, it was a lot of fun to write that way. And I think it’s fun for readers to pick up on that stuff too.

GK: I enjoyed how the book forced these characters from different classes to constantly bump up against each other. The wine and food truck guys serving upper-middle-class folks. Local art space owners running into fresh stepped from grad school cowboys. You also talked about how you wrote a lot of this while you were finishing grad school, and this got me thinking about how grad students are in an interesting place in terms of public perceptions of class. Because they’re participating in this process that is, admittedly, not accessible to everyone and yet it’s not like English and creative-writing grad students are receiving massive stipends, oftentimes the funding is slim and attached to teaching, and there’s no guarantee of a plush gig at the end of the rainbow. Which is all to say that their class status is complicated, and I really enjoyed how you complicated these perceptions of class and status throughout the book. Was this something you were aiming to do from the outset or was it a matter of writing from that headspace because you were in it at the time?

NRG: I have a lot of working-class pride. I can kick it at a dive bar and crack jokes with a group of roofers or bitch about a bad tipper with a fellow bartender. I remember feeling a bit like a traitor going to grad school at first. I was in my thirties and was leaving hard work and a working-class career to go into this perceived snobbishness and nerdom. And I can say that, even with the stipend, Bowling Green was the most stable my life ever was, jobwise.

Another thing I thought about a lot while writing were the artists in my hometown, many of whom have MFAs but also work at factories and make art in their garage. There are also all these high-school-dropout artists who make equally inspired art. A big part of Delinquents was inspired by the fact that I don’t see many stories about artists and academics outside of the coastal artistic meccas. But there are some brilliant artists in Mansfield, Ohio. They’re just so often overlooked, flown over.

Class is also a lot different in small towns. You run into everyone every time you go out. The wealthy factory owners who take advantage of their employees by paying them low wages drink at the same brewery as their artist/press operators. While those separations of class exist, they’re also in your face a lot of the time. That doesn’t stop rich dudes from being dickheads, being inconsiderate like the character Scusi in “Sever the Head,” but it does mean that you have to see each other as people. It takes a bigger stretch of the imagination to objectify or stereotype those from other classes. And even the wealthy people, they aren’t fancy like big-city wealthy people. We’re all overlooked to different degrees. I wanted to capture that, to kind of emphasize that overlooked places like Mansfield or Westinghouse have their own communities of artists. Maybe don’t fly over next time. Stop. Say hey.

GK: To build off that, why was it important to you to have so many of the characters write? Sometimes it feels like the writers in stories are so often stumped by or conflicted over very writerly concerns that feel disconnected from a non-writing audience: deadlines or publications or what have you. But it seems like you’re using writers here who aren’t fretting about those concerns as much as they are using that framework to consider how they’re telling their own stories or even thinking of their own myth-making. For example, Dallas wanting to “preserve [his] legacy.” Or the cowboy being aware that him being a cowboy was “an identity thing” that “felt cozy.” Can you talk about that decision?

NRG: Honestly, I often find fiction with main characters who write a bit cringy. And I was a bit worried about being called out on that. The opening story, “Delinquents,” is narrated by a guy who wants to be a writer but gets so involved in a pill-mill ring that he has trouble finding time to write. That story is one of the most autobiographical ones in the collection. When I was using, the hustle took up all my time, all my headspace, and I couldn’t get anything solid down. When I got clean, a lot of people encouraged me to write about my experience with drugs, but I couldn’t get the writing to work. It’s hard to tell a story that I’m still trying to figure out or one that’s actually many stories. A drug story is never just about drugs. So, with the title story, I was really trying to figure out how to write about my own drug use just as the narrator is figuring out how to tell his story.

Dallas is actually modeled after an old dealer I rode around with back in the day. He was very concerned about his legacy, and we often brainstormed, half-assedly, about me writing his memoirs. But he was a small-time middleman and a shitty father. I still don’t know what legacy he thought he’d pass on. Call it sad or prideful. The dude passed away last I heard and I’m not sure many people beyond his family even paid attention.

But, and this may sound a bit arrogant, I do think that Delinquents is there to preserve some sort of legacy. I think many people in small towns like Mansfield write or make art because they want to be seen or because they want their art to be seen. A lot of my characters are trying to figure out life, how to live, and a lot of times they do that through writing. They want to be seen, so they share that art or writing. If I can get people outside of a small town to read about the small town, to laugh about it, maybe visit, I can help those people be seen.

Gene Kwak has published in The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Rumpus, Lit Hub, Wigleaf, and Electric Literature among others. Go Home, Ricky! is his debut novel and was a Rumpus October Book Club Selection, was featured in Vanity Fair magazine and Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, and has garnered rave reviews from Publisher’s Weekly and Booklist among others. He is also the winner of the 2022 Poets & Writers Maureen Egen WEX Prize, has attended workshops at Tin House and Yale, and soon plans to attend a residency through Ragdale. He is also a Periplus mentor and in the fall he will be an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Oklahoma State University.

More Interviews