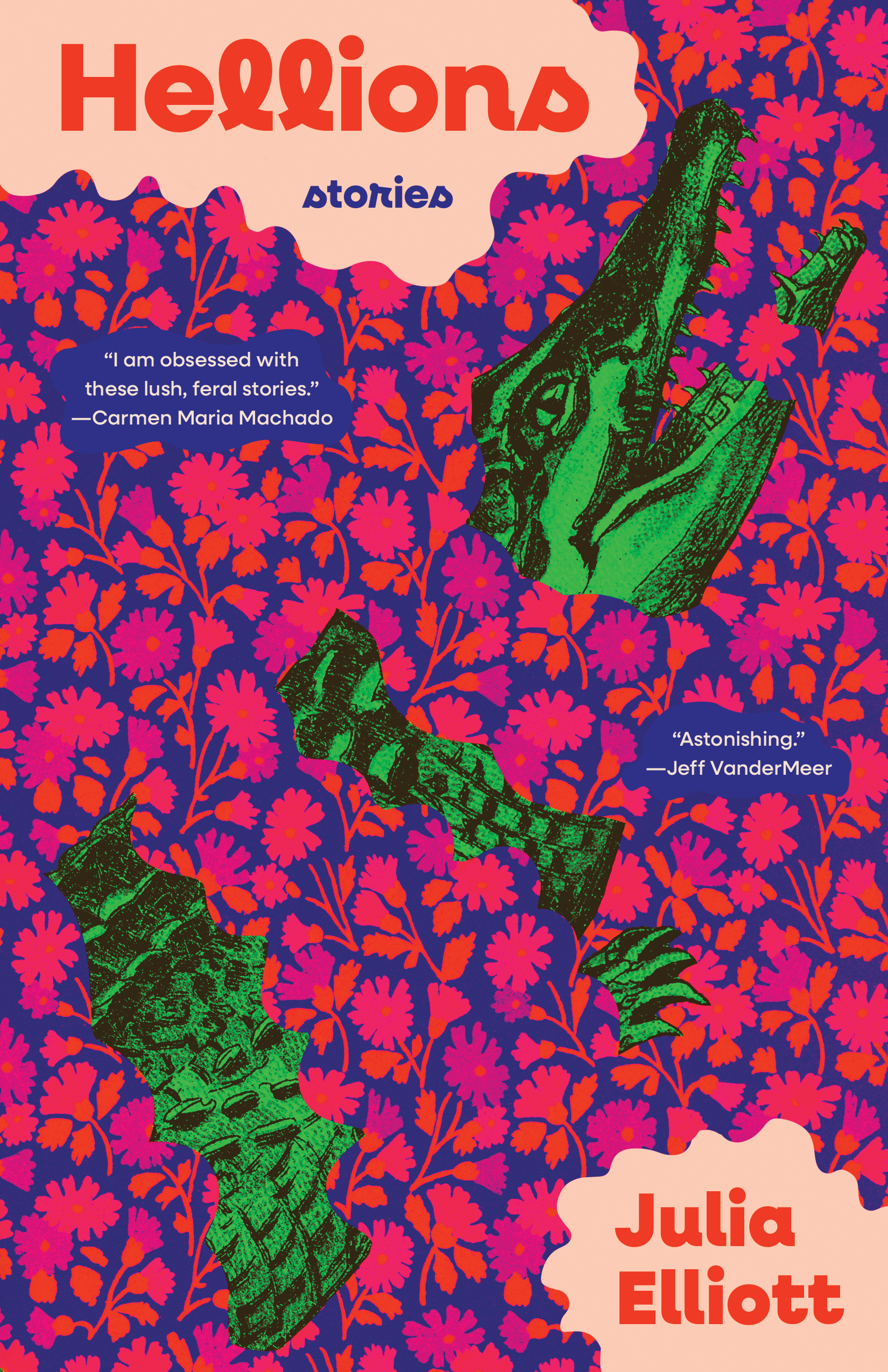

A Fresh Blend of Southern Gothic Weirdness | Julia Elliott’s Hellions

Reviews

By Adrian Van Young

In the story “Erl King”—one of the strongest and most memorable in Julia Elliott’s invariably strong, memorable new collection, Hellions (Tin House/Zando, 2025)— a young female college student finds herself in thrall to a powerful older man known only as the Wild Professor, a shameless, Andrew Lytle–esque senior faculty member who lives in a cabin among dark hills on the outskirts of a small Southern university. But the Wild Professor in “Erl King” is more than just lecherous; the young college student, who is also the narrator, gives herself over abundantly to his strange, sylvan magnetism, disconcerting and compelling the reader at once. “He was a feminist, he said,” the narrator tells us, “and we were full-grown mammals who shed menstrual blood. In the firelight, he looked younger, fine-boned, with a gold-green pre-Raphaelite gaze.”

If you’ve read the story of the same name by the British literary necromancer Angela Carter, from which Elliott takes direct inspiration, it should come as no surprise that Elliott’s Wild Professor is also more than human. Part satyr, part minstrel, and alllllll lover—albeit of the profoundly age-and-status-inappropriate variety—Elliott’s erl king, like Carter’s, seduces the narrator into an unorthodox living arrangement in his hill-country cabin while teaching her the ways of the lush, fairy-haunted woods that surround her. Not to mention forcing her to bear witness when “bone nubbins crack through his skull and flare into antlers. . . . Black hair sprouted from his scalp,” Elliott’s narrator says, “and flowed down his back like a cape. He grew six inches. He climbed out of his pants. He cast off his shirt, puffed up his chest, and scratched his furry thighs.” Gradually, then, like some sort of sorcerous STD, the Wild Professor’s shape-shifting gene begins to infect the narrator. “My skull burned,” says the young narrator. “I fingered the bumps on my cranium. At last, I felt damp bone pushing though. Blood seeped into my hair.” And yet, instead of cursing her to wander the woodlands in purgatory, the newly minted satyress discovers in her transformation a carnal, primordial power that strengthens as the Wild Professor’s declines: “I craved atmospheric electricity and the blackness of forest soil. I craved roiling clouds and the scent of my own wet fur. I wanted to climb a rocky hill and gaze upon the raw sublime, watch lightning jag from heaven to earth, catch the silhouette of some dangerous new beast galloping toward me across the meadow.” In this as in many of the best stories featured in Hellions, a seemingly powerless young woman—or women—willingly loses herself to an alchemical transformation at the hands of an otherworldly force only to discover herself in ascendance, becoming who she truly is.

Angela Carter’s story “The Erl-King,” on the other hand, in which something similar to Elliott’s takes place, comes from Carter’s groundbreaking and florid 1979 short story collection, The Bloody Chamber, a book-length reengineering of popular European fairy tales—the grotesquely tweaked boilerplate narratives for stories widely known as “Bluebeard,” “Beauty and the Beast,” “Puss-in-Boots,” and “Sleeping Beauty” among them. (The tale of the erl king, as adapted by both Carter and Elliott, comes more generally from German folklore and a long poem by Goethe.) And just like the stories in Elliott’s Hellions, Carter’s are often unapologetically and primordially feminist in theme and affect. In writing The Bloody Chamber, it was Carter’s oft-cited intention not to do “versions of . . . fairy tales, but to extract the latent content of the traditional stories” for an adult literary readership. That aside, the stories that make up The Bloody Chamber are largely recognizable by their popular source material; in part, that’s what makes them great. Whereas the stories in Hellions are full-throated, grown-ass Southern Gothic fairy tales of seemingly original extraction; that’s what makes them great—and fresh.

In “Bride,” another standout from Hellions, a self-flagellating nun in a plague-stricken medieval convent sheds the bramble-scarred skin of her devotion to God in favor of pursuing increasingly decadent and eventually downright heretical pleasures. “The Maiden,” a marvel of first-person-plural narration, tells of a gaggle of hardscrabble teens obsessed with a neighborhood trampoline who encounter an uncanny young gymnast named Cujo, the daughter of backwoods, dulcimer-making hippies, who leads them away from a safe, simple world. “Flying” is a lyrical jaw-dropper narrated in second-person direct address (Elliott, seemingly somewhat of a craft wonk, covers nearly every literary POV over the course of her collection). In this tale, a struggling emasculated yeoman surrenders himself to a woodland succubus in a moment of weakness only to discover that what’s given freely cannot be freely taken back. In “The Mothers,” which reads like a mash-up of Alice Munro and Carmen Maria Machado, an artist colony that caters to women with young children harbors an eerie atavistic secret in the form of animal-masked kids who emerge from the nearby woods. And in “All the Other Demons,” a teen girl and her siblings in the crosshairs of a failing marriage live through the sublimely dread-soaked weeks that preceded William Friedkin’s horror classic The Exorcist being aired on national television.

As one might be able to discern from the loglines of many of these stories, Elliott is a genre-blending writer, making robust use of a postmodern literary technique that has been made much of in the last several decades, particularly in the work of story writers such as Machado, Karen Russell, Matt Bell, and Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah. In Hellions, Elliott adeptly blends the narrative conventions of historical and gothic (“Bride”), Southern Gothic and coming-of-age (“Hellions”), horror and fairy tale (“The Maiden”), and even sci-fi and realism (“Moon Witch, Moon Witch”) to create narratives that are both singular and compelling. Yet where similar stories in another writer’s hands can sometimes show the seams between the genres themselves, in Elliott’s, the layering and transitioning among formal conventions are all but seamless; for a writer so entrenched in the vicissitudes of craft, Elliott’s is largely hidden. She might just be one of the best genre blenders to shed her human skin and screech.

Adrian Van Young is the author of three books of fiction: the story collection, The Man Who Noticed Everything (Black Lawrence Press), the novel, Shadows in Summerland (Open Road Media), and the collection, Midnight Self (Black Lawrence Press). His fiction, non-fiction, and criticism have been published or are forthcoming in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, Black Warrior Review, Conjunctions, Guernica, Slate, BOMB, Granta, McSweeney’s and The New Yorker online, among others.

More Reviews