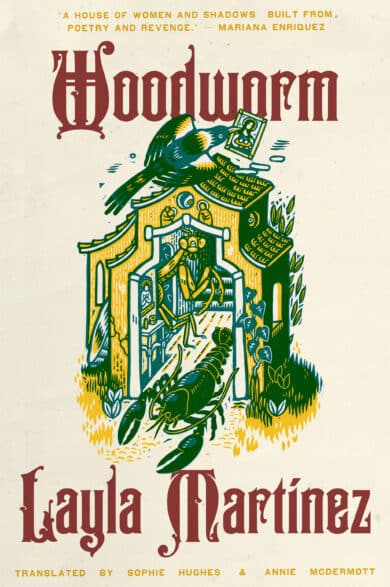

A Gothic Fable of Female Revenge

Reviews

By Cory Oldweiler

Much like the specters that often haunt its pages, gothic fiction as a genre has proved unwilling to quietly fade away, continuing to clamor for attention more than 150 years after its arguable heyday during the Victorian era. That high point should be qualified, however, as referring only to works originally written in English, because for Spanish-language authors, the golden age of gothic is happening right now, led by a remarkable group of Latin American writers who have embraced and adapted the genre’s conventions to yield significant commercial and critical successes over the past decade or so. Layla Martínez hails from Spain, not Latin America, but her debut novel Woodworm, a gothic haunted house story with a modern social consciousness, so seamlessly feels like part of the recent transatlantic trend that if it were set in the outskirts of Buenos Aires or Mexico City instead of the central plains of La Mancha, I wouldn’t have blinked an eye. For English-language readers, Wormwood also slots into the current craze thanks to its translators, Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott, who have both played prominent roles in the Latin American horror boom and here deliver another well-considered and distinctive translation.

In addition to its Latin American imprints, Woodworm pays homage to genre icons like Edgar Allan Poe and Shirley Jackson, yet remains a deeply Spanish novel, deriving from considerations of social class and political history that are specific to twentieth-century Spain but universal enough to resonate with international audiences. The story is also a deeply personal one for Martínez, born from the fact that her maternal great-grandfather “lived off women,” as she writes in the novel’s acknowledgments, by running a brothel. As depicted in the novel, the business, which began in the years leading up to the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), was not a place where autonomous women willingly chose a career as sex workers, but rather a place where enslaved women were forced to turn tricks, first in a stable and then in an abandoned mill. Using the profit he makes from women’s bodies, the great-grandfather builds a house for his wife, and thereby bequeaths his original sin to the women in his family.

Woodworm chronicles four generations of these women, all of whom are unnamed—great-grandma, grandma, mother, and daughter—and all of whom cannot escape their domestic legacy. The retrospective story is told by the house’s current residents, the daughter and grandma, whose perspectives alternate chapters; the mother disappeared as a teenager, presumably abducted. The daughter emphasizes that she intends to be an honest narrator—“I want to tell you things exactly as they happened”—though in the next chapter the grandma tells readers that the girl “lied to the police and she lied to the judge and she’s lied to you as well.” That alleged deception relates to the daughter’s role in the disappearance of Guillermo Jarabo, a boy she tended to as a nanny. Guillermo comes from a wealthy family, which in the novel makes it feel like his life “matters” more: “This world wasn’t made for those children to disappear.” Martínez perhaps further highlights this dichotomy by giving the child a name, unlike her lower-class female characters. When the novel opens, the scandal has been sensationalized in the media, but the girl has been released from jail for lack of evidence and returned to her grandma’s home.

When the family house was built in the 1930s, it was a “grand building for a village like this . . . but not so grand that the rich saw [its owner] as a threat.” It had electricity, but just enough to power “a single bulb on a long cable.” Decades later, the grandma sees the house as “a curse, a curse my father put on us when he condemned us to live out the rest of our years between its walls. And we’ve been here ever since, and here we’ll stay till we rot and for a long time after that.” They won’t rot alone, as the house is “chock-full” of shadows that pounce on visitors and inhabitants, twist their guts, make their teeth fall out and their “insides shrivel up.” People disappear into the wardrobe, see the contents of drawers and cupboards egested, and quickly learn to never get lured under the bed. These ghosts may have first appeared as a consequence of the house’s origin, but now they are drawn by the grandma, who practices sympathetic magic and communes with the saints: “People only come here when they’ve tried everything else, when the day the week and even the years have got them cornered and their one remaining option is to have the old woman pray to the saints or perhaps to the dead, though it’s all the same.”

The psychological burden of the house manifests for the grandma partly as a “gnawing restlessness, that woodworm . . . that bastard itch that won’t leave you in peace or let you leave others in peace either.” When the daughter accepted the nanny job with the Jarabos, the grandma knew “that thing had grown inside her just like it had with my mother, just like it had with me.” Woodworm refers specifically to the larva of certain beetles that infest untreated wood. The insects are especially pernicious because they have a three-to-four-year life cycle, meaning that by the time they reveal their existence, by boring a hole and flying away, they have spent years destabilizing their host and laying eggs. It is also worth noting that the novel’s title in Spanish, Carcoma, colloquially means anxiety.

Hughes and McDermott capture this “gnawing restlessness” linguistically by using onomatopoeia. In the original Spanish text, Martínez created various words, including cracracra and rarrarrarra, to indicate the itch of the woodworm, but Hughes and McDermott standardize the coinages to cracracra, which appears a half dozen times throughout the novel. The origin of the sound is linked to the actions of the great-grandfather during the last days of his life, spent under circumstances—which I won’t spoil here—that yield a neat lexical legacy. Other repetitions in the text subtly echo the uneasy feeling as well, as when the daughter describes her grandma as a spider “staying still still still as can be till at last it’s time to spring out,” or explains that everything in the house “gets inside you and scratch scratch scratches away.” Another stylistic choice that evokes this repetitive itch is a tendency to deconstruct a series of clauses so that the nouns and verbs clump together, as with “her pain her guilt her sadness her innards ripping tearing rending.”

McDermott and Hughes’s considerable skill is also on display when Martínez is having her characters emphasize class differences via dialect. The translators handle this potential challenge by simply using Spanish words, but in ways that clearly enable the reader to see what is happening even if they don’t speak a word of Spanish. In one instance, a woman explains how “the other day he said comío instead of comido and I swear I almost packed my bags there and then.” In another, the daughter explains how Guillermo’s mom “sounded so good, so private school, not a single muchismo instead of muchísimo or bonico instead of bonito.”

These class issues are critical to the story, playing a role in the disappearance of Guillermo and the mother. Despite the village setting, there are haves and have-nots, with the Jarabos representing the haves and the daughter and grandma the have-nots. These distinctions originated before Franco’s failed coup kicked off the Spanish Civil War and only intensified with the postwar denunciations and purges that roiled the country. Class dictates profession in the village. Whereas the Jarabos own a winery, the grandma’s family is only permitted to serve, tailoring clothes, cleaning houses, and doing other menial labor. Like her granddaughter, the grandma worked for the Jarabos, which partly explains why she is so dismayed when the girl takes the nanny job. The younger generation, including at one point the daughter, dreams of escaping this fate by going to Cuenca to work or Madrid to study, but generally only “rich kids” get out. The daughter has, like her grandma, accepted her fate: “The women in this family only leave when we’re forced, in my case when they locked me up and in my mother’s when they took her.”

The novel’s only real shortcoming is its timeline. The grandma is born in 1937 (“My mother gave birth to me five months” after the first months of the civil war) and gives birth to the mother at age twenty (“I served . . . between the ages of ten and nineteen” and “stopped working . . . before I started showing”). Since the mother subsequently gives birth then disappears while still a teenager, the latest the daughter could conceivably have been born would be 1976, meaning the early 1990s are the logical timeframe for the opening of the novel, which makes it difficult to understand how the daughter has a cell phone and the neighborhood “gossip and lies” go “viral on social media.”

Woodworm has a lot to say about class distinctions, and none of what it says is subtle, with the text often serving as the subtext, as when the daughter says, “To the police I said he’s a restless child with an independent streak, which is what teachers at fancy schools tell the parents of unbearable children and those parents think it means their kid’s going to revolutionize robotics when really it just means no one can stand them.” Near the end, the messaging and narrative start to grow a bit repetitive as the grandma and daughter echo each other as well as previously stated themes and complaints, but a couple plot developments slowly reorient the story’s motivation toward revenge. “I knew that once we poor folk started collecting our debts [the rich] wouldn’t have so much as a pigsty to hide in,” the grandma observes. She’s right, of course, because once you’ve got that gnawing itch, sometimes the only solution is to scratch scratch scratch it.

Cory Oldweiler is an itinerant writer who focuses on literature in translation. In 2022, he served on the long-list committee for the National Book Critics Circle’s inaugural Barrios Book in Translation Prize. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe, Star Tribune, Los Angeles Review of Books, Washington Post, and other publications.

More Reviews