A Massive Living Mural

Reviews

By David Leo Rice

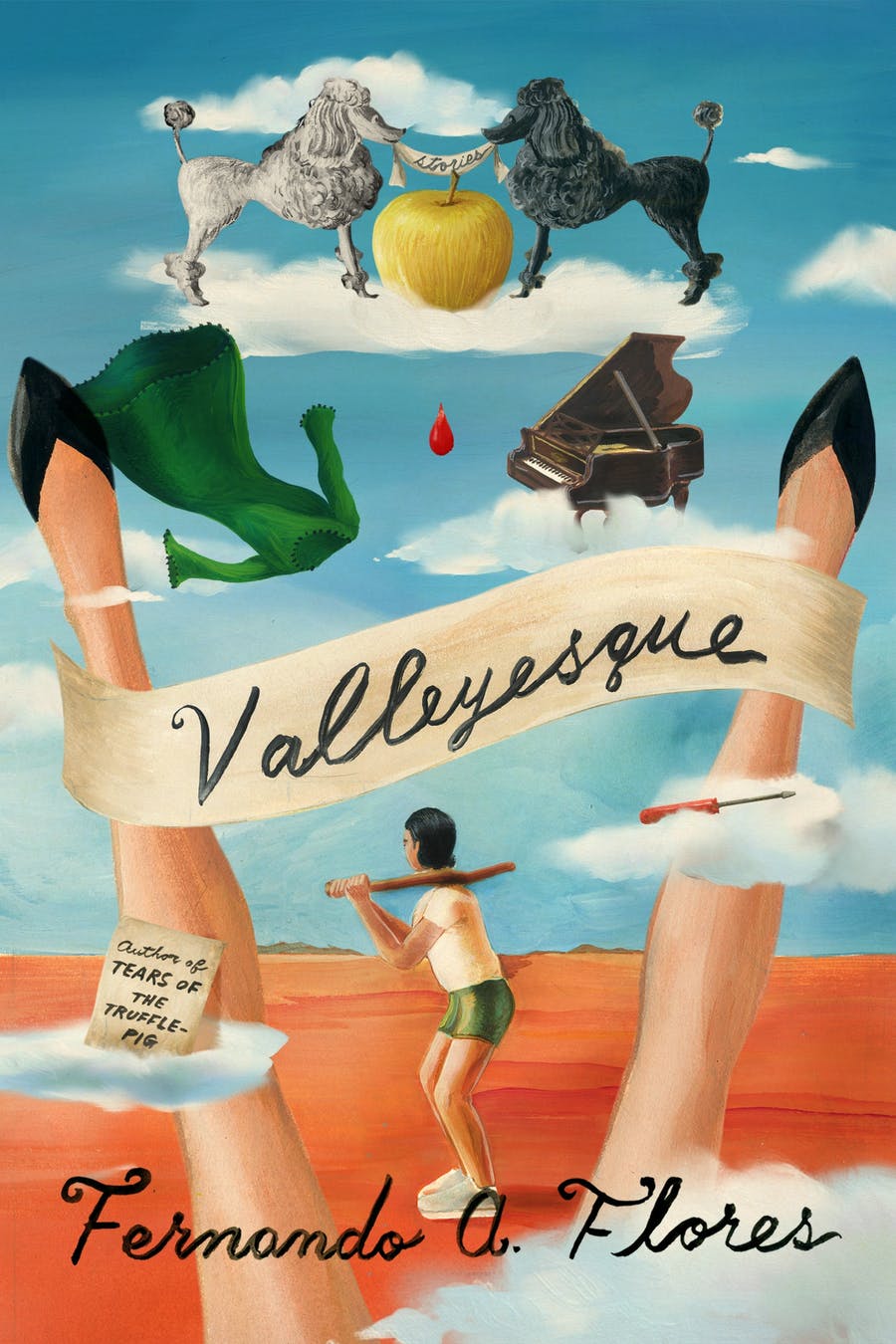

The dozen or so stories in Fernando A. Flores’s second collection, Valleyesque, seethe and seep together into a design that can never be seen all at once. A psychedelic border landscape of forgotten towns, half-empty cafes, and sun-blasted roads, the Valley of the title is the Rio Grande Valley between Texas and Mexico. But it’s also the more abstract and ominous valley where “the new anti-life force is breaking through,” according to the William S. Burroughs quote that opens the book. In this Burroughsian valley of the dead-living and the living-dead, Flores traces the lives of quietly eccentric artists and writers as they move through a larger, stranger framework, never asking what’s real and what isn’t, nor ever positing that any such distinction exists. Altogether, this valley is a realm not so much of lost souls as of meandering ones, feeling their way along like lines of paint, helping to flesh out a vibrant and complex design that only the reader can appreciate in full.

Many of the stories here involve historical figures—Chopin, Zapata, Nostradamus, Simón Bolivar, Proust, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, Lee Harvey Oswald—either as actual characters or as points of reference. But these figures exist always in a translated or transposed form, themselves but not themselves, as in a Bardo where our world has somehow both ended and continued at once. Either way it’s a world haunted by an ever-loosening version of its past, or perhaps only by the persistent fantasy that any such past occurred. These stories are not straightforward reckonings with history, nor are they satires or dismissals of it: they’re something more slippery and playful instead, sly and oblique, like ghosts or people dressed as ghosts performing a tragicomic roadshow for a motley array of strangers on a sweltering afternoon.

More than once, this Bardo reminded me of the worlds created by Antoine Volodine, the French writer who, through innumerable books attributed to innumerable pseudonyms (including, perhaps, that of Antoine Volodine), has created his own Bardo, a kind of post-Fall account of the world as we know it once it’s no longer that at all—once whatever’s coming has come. In both Volodine’s and Flores’s work, there’s no other world, and yet this world is no longer itself, if it ever was. Perhaps, many of the stories here suggest we only think the world was once another way, when actually there has never been anything but whatever happens to present itself before us, sticky with a kind of folklore whose source is ultimately unknowable.

Along with these transfigured historical beings, Valleyesque overflows with enchanted objects: a baby made of earwax, a painting that seethes bees, an impossibly spacious used clothes depot, and a “thin gray fabric that rippled like liquid” and may have been left here by aliens. None of these objects consent to play a predetermined role in the stories they appear in, as none are overt literary devices or pieces in any known game. Instead, they announce their existence on their own terms, fully-fledged entities integrated into the mural’s obscure but intact logic, there to be admired and reckoned with as they are. As in the canvases painted by Remedios Varo, whose name also crops up in these pages, the living objects in Flores’s stories take up real space and have real dimensions. They cast shadows and have weight. One can absorb them or not: the narrators who relay them to us aren’t bothered either way.

Still, despite the gentle and relaxed tone that these narrators tend to employ, this is by no means a world without suffering. The violence of life on the border comes through powerfully here—especially in the gruesome events of “The 29th of April”—but it’s a kind of violence that likewise informs the mural, offering no prospect of cessation nor any impetus for revenge. Violence is simply part of life here, a shadow in the valley, within which these characters have no choice but to walk, caught up in their own dramas—their many humble, heroic efforts to make a living and a life—while remaining aware that this may indeed be the Valley of the Shadow of Death, through which runs the ultimate border. As Burroughs warns at the outset, this valley “exerts a curious magnetism on the moribund,” among whose number we must all count ourselves.

“At what point does a wall become a mural?” wonders the muralist Eduardo Salamanca, who perhaps serves as a miniature self-portrait of the author, in “Zapata Foots the Bill.” He goes on to propose several possibilities, but it’s a testament to the grandeur of Flores’s design that this central question—an analog of the question of whether the border is a limit or a threshold, the edge of the world or a portal between worlds—never resolves into certainty. Nor does it ever cease to generate the strange magic that binds these tales together.

David Leo Rice is a writer living in New York City. His books include A Room in Dodge City, A Room in Dodge City: Vol. 2, Angel House, Drifter: Stories, and The New House.

More Reviews