A Perpetual State of Half-Sleep: An Interview with Troy James Weaver

Interviews

By Wilson McBee

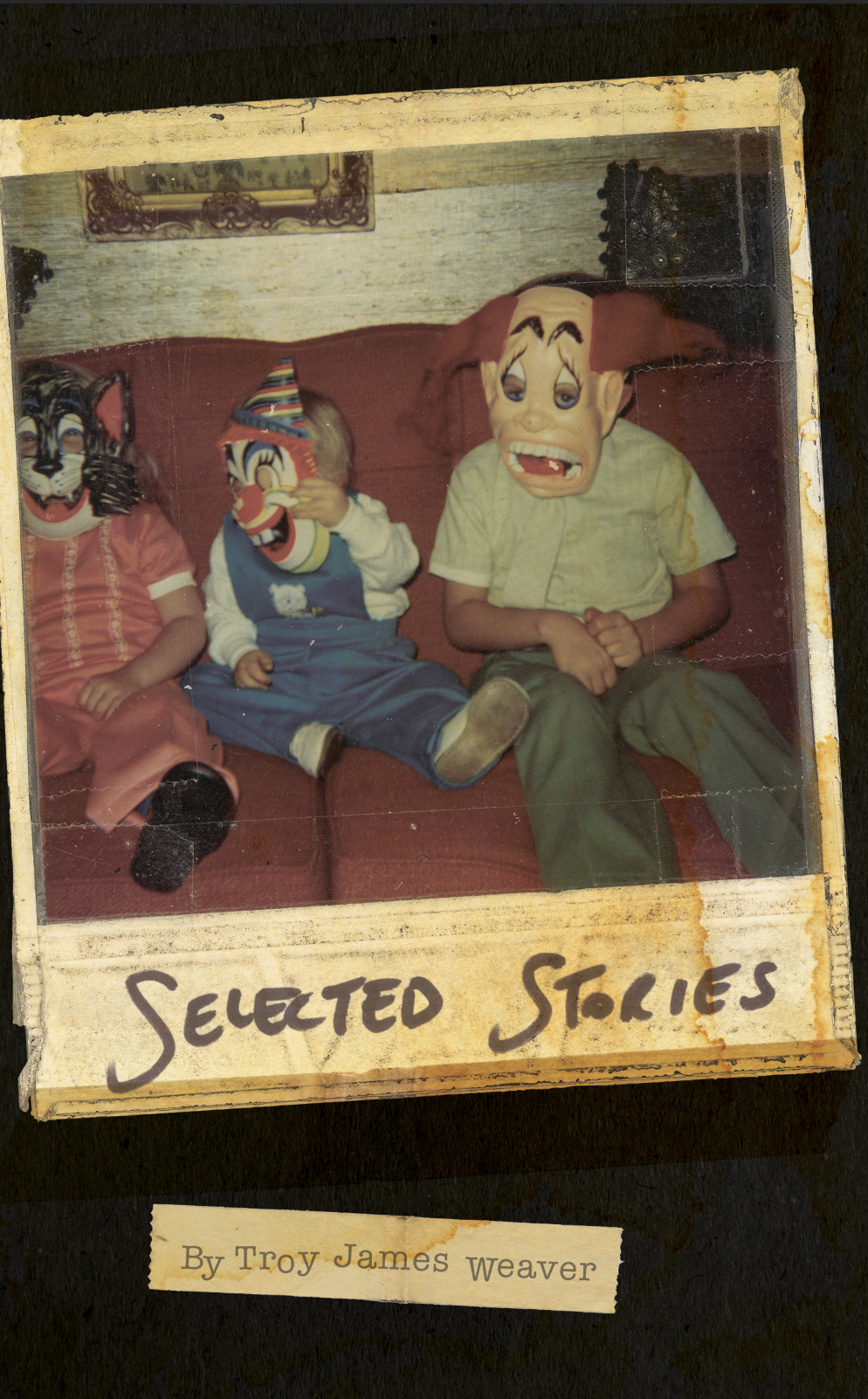

The characters in Troy James Weaver’s latest book, Selected Stories, are in battle with traumas small and large. Some wear their trouble like jewelry, gaudy and eye-catching, while others haul it behind them like an overstuffed suitcase, a miserable and rate-inhibiting burden. Weaver’s fictive bursts—few of these stories are longer than a few pages—zoom us in and out of lives sticky with hurt, leaving a grimy residue of one-liners, often dialogue, in the mind that’s hard to wash away. “Maybe your mom should peg your dad” is the bit of advice offered by one college student to another, the daughter of estranged parents. A flat-earther extends an unforgettable come-on: “I’ll show you my edge.” A wounded veteran of the war in Afghanistan, after having snuck out of a VA hospital to drink beers in a liquor-store parking lot, defends his misbehavior with an excuse that soon takes on a chilling implication: “Not like we killed anyone.”

These moments occur against a background of classic Middle American locations—a construction site, cheap motel rooms, gas stations, Applebee’s, the ER—and Weaver is clearly descended from the rich tradition of writers like Larry Brown and Bobbie Ann Mason who are sometimes grouped under the limiting umbrella of “dirty realism.” A native of Wichita, Kansas, Weaver still works a day job, and, as the interview below reveals, he approaches his writing with a laborer’s dedication. But, as with the work of his predecessors, Weaver’s fiction shouldn’t be defined simply by its gritty subject matter. More important, these stories exhibit a sophisticated understanding of human desire, a subtle facility with language, and an openness to the unexpected, proving that Weaver is a young writer to be watched.

WILSON MCBEE: You have mentioned in previous interviews that you have maintained a full-time job while writing. Your novel Marigold is based on your experience in the floral industry. Are you still working a day job now, and if so, how has that experience informed the stories in Selected Stories?

Troy James Weaver: I still work in wholesale floral. The job informed the stories in the book only in slight ways. I composite characters out of people I know and observe, so a full-time job functions beautifully to that end. Without it, I’m not sure I’d be able to write the way I do.

WM: You inhabit an impressively wide variety of characters in Selected Stories—a successful television writer, a high-school student, a wounded veteran, among others—and voice, even in the stories that are in third person, plays a big role. What kind of work does it take to capture the voices of these characters on the page? How do you know when what you have sounds right?

TJW: Voice is the most important thing to me as a reader. When I first discovered Barry Hannah, for instance, that first story in Airships, when I started reading it, I just thought, “Damn, I can hear this guy’s voice in my head”—it was just so clear. And then I found clips of him reading online. What I had heard in my head and what I heard on the screen were the same thing. I aim for that kind of concision.

I write with pen and paper, longhand. Edit. Rewrite. Edit. Type, print, edit, type, print, record myself reading, listen back, make notes on awkward phrasings, edit, print, on and on and on until it feels done. It is really just intuition at that point.

WM: Grief is a common thread running through a few of these stories. Characters are often mourning something, or someone. Is that something you were conscious of as you were writing the stories or putting the collection together?

TJW: No, not so much. I think that just happened as a result of losing loved ones while working on the stories. My grief worked its way in somehow. Grief is confusing. I only saw that thread after the book was put together.

WM: All of these stories are on the shorter end of the spectrum, and some are as short as a page. Yet they feel big and fully realized. How do you know when a story is finished? Does your work involve a Lish-ian amount of cutting and rewriting?

TJW: I cut a lot out. Some of the stories were twice to three times longer. One of them was 5,000 words at one point. Now it is 500. I don’t really have an answer. Some of them came out fully realized and I just had to change a few words around. It’s mostly intuition. I just know when I’m done with something. I also know when to trash things, too. That’s important. Also, having another set of eyes is always good. The oldest story in the collection is the last one in the book. The first paragraph was the third. I shared it with Brian Allen Carr. He said, “Take those first two paragraphs out.” And he was right. I wrote that one seven or eight years ago. For some reason I couldn’t let it go.

WM: A lot of your stories have what I sometimes call a “trap-door” moment—there is a turn, and everything falls away. As a reader, these are the moments I often return to, because they’re challenging and confusing. Kind of like reading a line of poetry that you love but don’t fully understand. One of my favorites is from “Someday Soon,” when the narrator’s tenant, Mrs. Crenshaw, blurts out, apropos of nothing, “I still have the knife that killed my brother.” I love how startling and strange that sentence is. Another one of these moments comes in “Orthodontics,” when one of the drifters taken in by the narrator suddenly starts going off about how the earth is flat, and then, later, the drifter’s female companion confronts the narrator with an offer to show him her “edge.” It’s both perfect and totally unexpected. As you were writing, did you know that that was where you were headed?

TJW: With Crenshaw and the knife, I think I was trying to reflect the narrator’s state of mind before you realize what that state even is. Probably the most unreliable narrator I’ve ever written. But it also foreshadows the violent reveal at the end. The whole plot happens in his head while he’s killing his cat. Whether or not I pulled this one off is up for debate. The only grounded moment is the last paragraph.

As for that drifter and her “edge,” I’d written the beginning and end of that story before the middle came to me, so it was all about getting all the points to converge.

WM: Ok, I will admit that I didn’t understand “Someday Soon” exactly that way! But I definitely picked up on the dreamy, surrealistic quality of the narration. I’m reminded of a Lydia Davis essay about dream journals. Davis describes an attempt to capture an event from everyday life in the language of a dream, and we learn that so much of the effect is in the writing, which I think happens in your story as well: the present tense, the absence of certain establishing details, the quick movement from one incident to the next. Was it a conscious choice for you to write the story in that dreamlike style, or did it emerge more from what you were writing about?

TJW: It wasn’t a conscious choice at first. That came in later drafts. I felt like since the character is in a perpetual state of half-sleep, the prose should be as well.

WM: There are a few other stories in the book that have a similar, almost-surreal quality. I’m thinking especially of “Preacher with Fruit” and “Post-Apocalyptic Boyhood with Paramedic.” They work really well, and testify to your range, given that you’re clearly so comfortable in the Barry Hannah school of vivid realism. When you’re writing a story, do you know which of these modes—realism or surrealism—you’re in? Can you switch from one to the other?

TJW: I always know which mode I’m in once I begin the first sentence. I’ve written so much on the realism side of things, which is fine—I enjoy it—but with the surrealism or whatever, I’m really just trying to challenge myself and embrace the possibility that the story may fail. I find a lot of enjoyment in that.

WM: Finally, a boring-but-still-useful question: What are you working on now?

TJW: A novel about a murderer who wishes to be arrested, then wishes to die. However, nobody takes him seriously (the police, Death), so he kills more and more people trying to state his case. More surrealism.

Wilson McBee is a staff writer for SwR.

More Interviews