A Porous Exchange of Mutual Creation | A Conversation with Nate Lippens

Interviews

By Lindsay Lerman

Nate Lippens is on a roll. Semiotext(e) has just reissued his first book, My Dead Book, and published his second, Ripcord. Fans of My Dead Book will be pleased to see that Lippens’s masterful use of Wildean bon mots and acerbic aphorism continues, but Ripcord is no mere continuation of what began in My Dead Book.

Ripcord wrestles with what it means to make art—and what it means to succeed, to fail, to do what it takes to pay the bills, to fall in and out of love, to be tender and violent and unafraid, to keep going, somehow. In Lippens’s books, the messiness of life is stylized, or sharpened into sensibility, but it is not covered up, ignored, or given a gloss so slick it lacks all relation to life, as we see, for example, in much of the writing of the terminally online. Both books are evidence of life lived gloriously, dangerously, and glamorously outside of or beyond the internet—which is not to suggest that they’re out of touch or irrelevant. On the contrary, their relevance is timeless. They are perilously close to the heart of art and the artist’s need for freedom.

Nate and I began emailing and talking over the phone back in 2021, just before his first book was published. Since then, each time one of us has published a book, we’ve interviewed each other. This is part three of our ongoing correspondence.

Lindsay Lerman: You were saying that you kind of enjoy your obsolescence.

Nate Lippens: I do—there’s something that suits me about being outdated as a person, kind of lost to time even as you’re still in its flow.

Nate Lippens: I do—there’s something that suits me about being outdated as a person, kind of lost to time even as you’re still in its flow.

LL: But what about cultural obsolescence? How stupid is it that we think youth is the only way culture advances? Like, I have way more explosive power than I did when I was twenty-five. I love how your writing rejects youth obsession.

NL: I’ve been kind of thrilled by my cultural obsolescence, of being out of the loop, out of importance. It’s something the characters in Ripcord wrangle with, watching their old world fade and a new and often indecipherable one replacing it. There’s something of the natural order in it and also, always, the marketplace. Youth obviously sells. Newness is the draw to everything—endless updates, twists on language, fashion. To me, it’s removed from anything I consider important. I take solace in not having a dog in any of those fights. I feel much more contentment and solidity now than I ever have. I like being middle-aged and out of the competition. I was never good at it anyway. Fortunately, I have friends who are in a similar mindset.

LL: That’s the beauty of friendship, though, and that always comes through in your work. That came through so strong in My Dead Book and also in Ripcord. Sometimes I think we spend too much time trying to know ourselves on our own terms, and there’s so much to be learned from letting other people tell us who we are. That’s very dangerous, of course. I love the way relationships are written by you and your narrator. I say “you and your narrator” because I feel like your narrator is a writer and you are a writer of your narrator, if that makes sense. I don’t necessarily want to call your work autofiction though, because your work is doing so much more than what people are reducing autofiction to in this moment. Are you and your narrator writing side by side? Does that make sense?

NL: I think of him more as a reader and notetaker than a writer. He jokes at one point that his friend Charlie always wanted to be a writer and Greer always wanted to be an artist and he wanted to be a character actress in the 1940s but there were a lot of obstacles. I see him as shaped by art and books and music but as someone who could never access those worlds. He could only ever be peripheral as a zine maker, a fan. He’s so many people I’ve known and also been. I don’t think of my writing as autofiction at all, but I do love stealing from that form and diaries and essayistic asides and aphorisms and getting them wrong. Of course, I use my own physical description and personal details but they’re more of a form to drape everything else over. I have to imagine the narrative for it to be real. Maybe part of it is that I’ve always thought I made more sense as an idea than as a person.

Friendship is the center of the narrator’s life. These are the ways he sees himself in the world. He would be lost without his friends. They ground him, help him negotiate the past and present, challenge and frustrate him. All those elements are important. Culturally, we tend to glorify either the individual, the loner, or the community, the person as a proper citizen, or the family member, but the smaller, closer, more tenuous work of friendship isn’t seen as important. I once had a younger gay guy, a doctor, tell me in the end it’s always family that gathers bedside and takes care of a dying person. I said, “Tell me you didn’t live through the darkest hell of the AIDS crisis without telling me.” My queer friendships are the ones that have sustained me, especially as I’ve aged. There’s a powerful shorthand, a way we check in on each other without making a production of it. Offhand lowercase love. The best.

LL: This is the strangest moment to be a writer. They keep telling us no one reads and no one cares and books aren’t important, but if you look up any global celebrity—no matter who they are, no matter what they’ve done with their lives, if they’re a model or a chef or an actor or whatever, if they’ve had a book ghostwritten (because few of them are writing their own)—the very first thing they will say in their profile is “author.” Always. And here we are, writing because it’s all we can do, and we never know if we’re going to get published, even if readers are really connecting with our work and our books are selling.

NL: I worked as a ghostwriter for a few years. Absolutely abysmal. I figured I would be a medium, some go-between to help shape people’s stories. But most were interested in the title of author and their personal brand and not at all in words. No natural rhythm, no voice, no love for language. And because they were wealthy, I fought to get paid every time.

The most miserable times in my life were when I tried to make a career of this thing, tried to sanctify it. I always hesitate at what to call this—nothing quite works. Maybe advanced reading. Like you’ve read so long that you can’t help but be a writer. It’s my favorite kind of communication. Novels do something nothing else can for me. And I like the illegitimacy, the fact people think of it as a dead form. Sometimes when I hear the term “gatekeeper,” I picture one of Edward Gorey’s illustrations. Ghosts behind cast-iron gates at a cemetery.

LL: I’m thinking about how gatekeeping is not always a bad thing. I’m glad my early work didn’t get published. It wasn’t good enough. I’m glad I had no money or connections to force my way in. It’s just that gatekeepers need a better calling than money and power.

NL: I’m glad the short story collection and novel I worked on didn’t get published. I look at them now and see the deep realist drag I was attempting, the nineteenth-century format, dreary little plot, people moving in and out of rooms. Character arcs I’ve never witnessed in life. Epiphanies! So, the gatekeepers did me a favor. I was trying to be in the wrong room at a table I would have hated. At the time, it felt too audacious to write like I think—fragmented, gnarly asides, marginalia, compliant. Too shameful. But then my life kept breaking apart and I saw I had to write how I am and ditch the realist, plot-driven, historical reenactment model with its pop-psych Christian hangover—resolution, closure, catharsis, salvation. Those are fleeting sensations, like something out of Nathalie Sarraute’s Tropisms. They’re not stations or states of being. Reflected light from a passing car at most.

Money and power is something gatekeepers and so-called tastemakers—or are they influencers now?—cling to because it’s measurable. One of the things I realized as the publication of Ripcord approached was that it isn’t necessary to do everything at once—a spasm of publicity. It can happen on its own dawdling schedule. Or anti-schedule. My Dead Book has had a long life from 2021 until now. Readers discover that book from other readers and it’s independent of the artificial promotional cycle. I’m doing events at my own pace and as I can financially afford them, so they will probably go on through the spring, or whenever I want.

LL: But I think we should feel very comfortable doing that, because the old system of determining in advance what’s going to sell and how it’s going to get to the audience—that’s all completely breaking down.

NL: They don’t know at all. You’ll hear of six-figure deals for a writer from some scene The New York Times has relentlessly pushed in dead-on-arrival Styles section pieces. When the Times is writing about famous publicists—I mean, the royalty of a six-block radius—they’re reaching hard. These books are largely about product and persona. The reader is seen only as a consumer. I’m pleased to be far away from all that, and now that I’m off most social media and have killed my news subscriptions, I will never know.

LL: Yes, and they’re full of fear too. Fear that the work won’t stand on its own. In ten years, one hundred years. That desperate fear that you won’t get to reap the benefits while you’re alive. I get it. I hope to be read well while I’m alive. No doubt. If I’m going to keep writing, I definitely need some resources and opportunities. I’m honest with myself about that. And so, I hope to see them, and in fact, I already am seeing them. That’s how I was able to come to Berlin. Someone wise said to me, “It’s going to come—everything will come—if the work is really speaking,” and I’m starting to see what they meant. In Ripcord, Greer expresses a lot of this with wisdom and cynicism and hope, too, I think.

NL: Greer has weathered a lot of scenes and moments where the art world and her practice has either been ignored, unfashionable, unsellable, or misaligned. But she kept going. I think an internal—I hate to say logic or necessity but something that arranges and is propulsive—is crucial. I never know where I’m going. I just have some faint direction—a first line, a last image, a voice—and I go until I have to make choices and those create the next ones. If it’s exciting to me as a reader, I can hope it will be for other people.

I definitely understand what you mean about resources and opportunities. Mine have taken the most unexpected turns, like going to London and doing events at Foyles and Donlon Books, and then having a day where Rich Porter and I went to six bookstores, and I signed copies. I got to meet the booksellers who made My Dead Book such a success there. It was one of the best weeks of my life. And then I went to Dungeness and Prospect Cottage the next day with Rich and Hesse K. When I returned to the US, I read in Milwaukee at a house series called the Bell Tower and the audience felt so tuned-in and open. None of these things were something I could have imagined.

LL: I’m so excited for these two books. It’s amazing to see your work getting the attention and the distribution it deserves. I’ve already told you it fills me with hope.

NL: Thank you so much. I think the way all of it happened was really natural and came from mutual respect and admiration. Both books got to be what they needed to be, to maintain the form I wanted for them. When I was looking for a publisher to reissue My Dead Book in the United States, editors told me they wouldn’t know how to publish and promote it.

LL: They seem to struggle to appreciate work that bucks certain trends and conventions. And they’re not necessarily savvy or skillful enough to say, for example, okay, this queer novel is also about so much more than queerness. So, can we find a way to make it play in multiple worlds? And let’s do it in an interesting way, you know, and let’s make this book come to life. They don’t do that. They just put the colorful-blob cover on it, and they give it mid-list treatment.

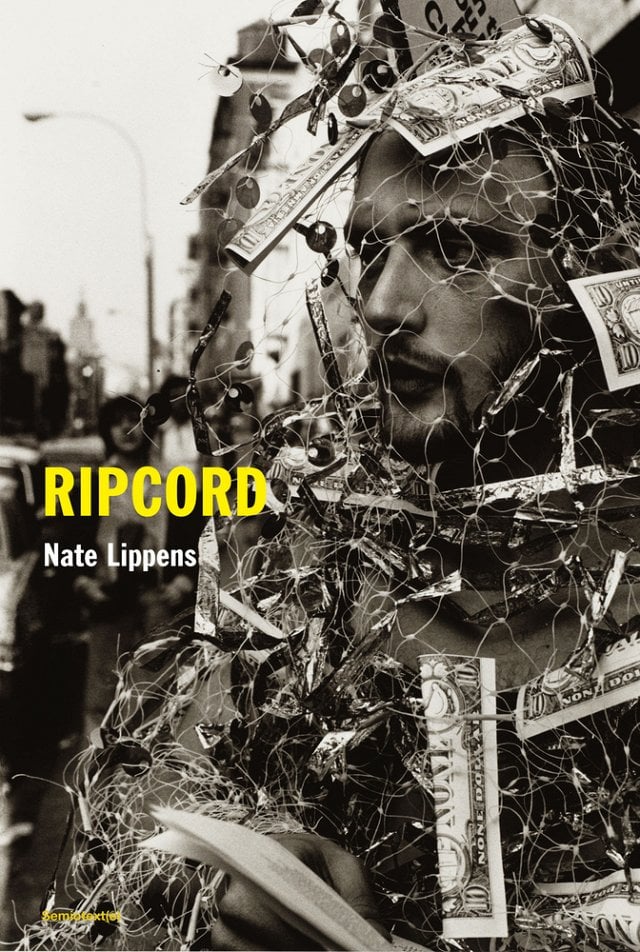

NL: The bubble tea covers. A bookseller told me the current cover color is yellow. Everything is yellow. Some brand strategist focus-grouped this and the decision is out: yellow sells. I joked with Rich that a different type of press would have nixed my Stephen Varble photograph by Peter Hujar in favor of an illustration of a man descending on a yellow parachute. No correlation with the content, just the title.

LL: You were saying earlier that you get a lot of leading questions, like How much have you been edited? As though you couldn’t really have done this, could you? I get a lot of No, no, no, you’re not real. You’re not real. It’s all smoke and mirrors. And I don’t know. What else can I say other than I did this, and I am still doing it. And I’m just getting started.

NL: I think there’s the assumption—thanks Gordon Lish—that working-class writers must somehow be pruned and guided. Clearly, we don’t have the sophistication and ability to edit ourselves. There are a lot of heavy editors at work at journals. I’ve pulled multiple stories over the years. I’m extremely protective of my writing, especially when someone hacks away with the assumption something must be wrong and needs to be fixed. I edit and rewrite and edit over and over as I go. I’m ruthless. I had a great experience with Robert Dewhurst at Semiotext(e). He’s a great copy editor, really sensitive and respectful. Not someone cutting a third and retitling the story at their whim.

LL: No, I don’t want that. I believe that artists are the mediums or channels for so much of what’s happening in the world, and if that gets edited into a particular style, what’s the point?

NL: When I worked as an editor, I saw my role as being at the service of the writer and the reader. Ideally, they’re the same person. It’s a porous exchange of mutual creation. That’s always my aim when I’m writing, to break that barrier.

LL: I keep coming back to the closing scene of Ripcord, and how it feels like the narrator is really in motion, despite an implied motionlessness, or a history of motionlessness. “I’m not on my way to a plane or a bus. I have an all-day catering gig.” And yet, he is going somewhere, and he knows what he wants. “I lean forward and say to the driver, ‘Could you put some music on?’” This has me wondering: what happens if the narrator’s life changes—maybe even changes a lot—and what if he is on his way to a plane or a bus?

NL: I could definitely see that happening. And probably in the most unlikely of ways. He’s yearning for escape, which is often when it doesn’t happen. When the yearning moves on and life seems static is usually when something comes and unsettles it. At least, in my experience.

Lindsay Lerman is a writer and translator. Her first book, I’m From Nowhere, was published in 2019. Her second book, What Are You, was published in 2022. Her essays, interviews, short stories, and poems have been published in the Los Angeles Review of Books, New York Tyrant, The Creative Independent, Archway Editions, and elsewhere. She has a PhD in Philosophy from the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. Her translation of François Laruelle’s first book, Phenomenon and Difference: An Essay on Ravaisson’s Ontology, was published in March 2024. She lives in Berlin.

Nate Lippens is the author of two novels, My Dead Book, a finalist for the Republic of Consciousness Prize, and Ripcord, both published by Semiotext(e) and Pilot Press (UK). His fiction has appeared in many anthologies, including Sluts, edited by Michelle Tea (Dopamine, 2024) Little Birds (Filthy Loot, 2021), Responses to Derek Jarman’s Blue (Pilot Press, 2022), and Pathetic Literature, edited by Eileen Myles (Grove, 2022).

More Interviews