A Productive Tension | An Interview with Kathryn Scanlan

Interviews

By Zach Davidson

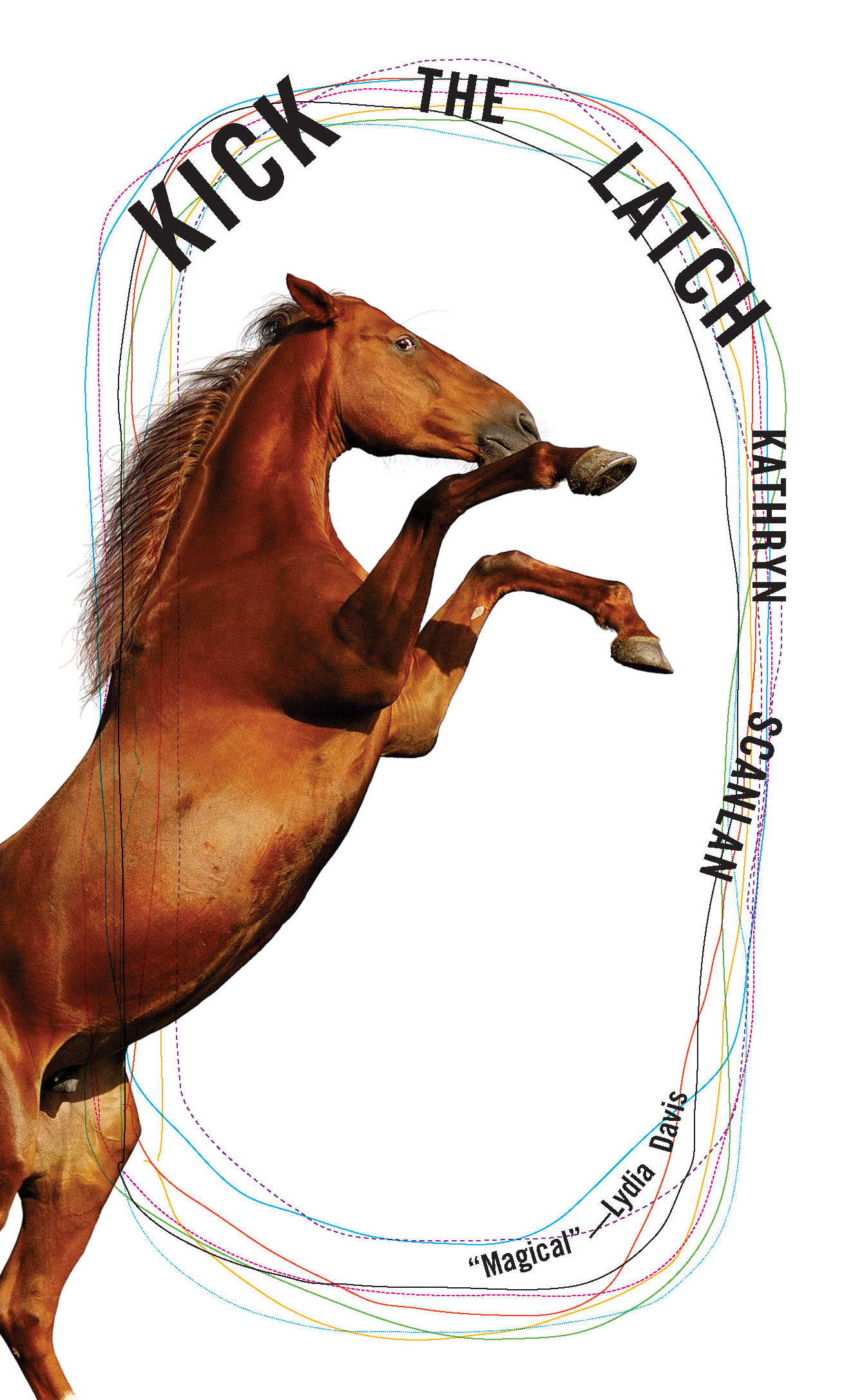

The paragraphs of Kathryn Scanlan recall flat plains: they are without ornament, and their candidness may stun you. In Kick the Latch, the geography of Scanlan’s prose echoes the frankness of her narrator: Sonia, a horse trainer. The novel—based on a series of recorded conversations between Sonia and Scanlan, both of whom were born in Iowa, where this first-person narration opens—exhibits the power of the unadorned. Through plain speaking, plain writing, Scanlan shows the everyday features of a life to be worthy of recognition.

Over email, I asked Scanlan to discuss how Kick the Latch bore on her own artistic practice, as well as to identify resemblances between her creative process and horse training—a rigorous editor of her work, Scanlan puts language through its paces as Sonia does thoroughbreds. We also spoke about how this novel is, and is not, like her two previous books: Aug 9—Fog, a kind of poetic collage based on a found diary at an estate sale, and The Dominant Animal, her collection of short stories.

Zach Davidson: Kick the Latch bears an assertive title with a forceful narrative to match. The events themselves happen in and against the flesh: Sonia is born with a dislocated hip; horses break down on the racetrack. Bodies of horses and humans are continually disrupted. As a reader, I felt like this was, in part, a tale of victorious survival. In what ways did the writing of Kick the Latch test you as an artist?

Kathryn Scanlan: At the end of my first conversation with Sonia, which lasted almost four hours, I stood up stiff, shivering, in need of a restroom, with an intense sunburn on one half of my face. I’d been sitting rigidly the whole time, listening intently, afraid to get up and break her narrative. Our phone conversations were similarly lengthy and intense—though I should add that it was also a lot of fun to speak with her.

Transcribing the recordings was tedious, physically uncomfortable. Approaching the transcribed material was overwhelming in terms of its volume, but I also felt anxiety about the responsibility I owed Sonia—I wanted her to approve of what I was doing. It was a challenge to shape and control the text in an artistic sense without straying too far from the person and the life it’s based on.

ZD: What role does syntax play in reverberating, on a formal level, the kind of collisions that riders endure, including Sonia, whose horse is T-boned?

KS: I wanted the book to have a kind of concussive force or physical impact similar to the roughness and speed of a race. But I think I’m always trying to arrange language in a way that feels blunt, abrupt, alarming, because life often feels that way to me—“you get hit”—

ZD: I also thought about Kick the Latch in terms of thresholds. In horse racing, competitors strive for their horses to achieve optimal performance. Trainers, jockeys, grooms, owners: they are all pushing their animals to the limit, sometimes past the limit—like, say, through the use of a “hotshot machine” or by taking blood from a horse’s neck prior to a race. At what point do you think a work of your own fiction has achieved its “optimal performance”? Are you able to detect when that next edit or addition risks, so to speak, endangering the health of the whole?

KS: I don’t know. Sometimes I feel confident in my ability to do this, other times I do not. It’s a critical and analytical skill, but it’s also intuitive. The passage of time is the only reliable way I’ve found to get a vantage on what I’ve done. A certain detachment seems necessary. I try to stand outside myself—to look at my work like a stranger might.

ZD: The book raises questions about the distinction between fiction and nonfiction. Sonia is a nonfictional person whose conversations you recorded and transcribed. Kick the Latch is a work of fiction. Returning to the issue of thresholds, I’m wondering: What boundary is crossed when a narrative goes from nonfiction to fiction? Do you regard Kick the Latch as a work of fiction?

KS: Yes, I regard it as fiction, a novel—that’s how I presented it to publishers, and I wouldn’t allow it to be marketed as such if I hadn’t—but I also like “fiction” as a sort of default or catch-all literary genre. The existence of a clear “boundary” between narrative nonfiction and narrative fiction seems unlikely—is it a single departure from fact, a single act of invention?—but I’m aware of a tension between the two when I write, and it’s a productive tension. To me, the idea of genre is useful as something to question, push against, make mischief with.

I like what Emily Stokes is doing at the Paris Review—she reconfigured the table of contents so that fiction and nonfiction are now grouped together as “prose.” As a result, I became aware that some readers thought an excerpt of Kick the Latch, published in a recent issue of the magazine, was an essay. And my editor at New Directions, who read the book without reading my agent’s cover letter first, thought it was a memoir. I like this friction—the feeling of wondering, “What is this? What am I reading?”

ZD: Kick the Latch, like your previous book Aug 9—Fog, begins with a nonfictional recording—in the case of Aug 9—Fog, a diary—that then, according to your artistry, is transformed into a work of fiction. How did the fictionalization process of Kick the Latch compare to that of Aug 9—Fog?

KS: Aug 9—Fog became fiction through my selection, arrangement, and edit of what was essentially a tiny fraction of the five-year diary’s original material—a written document, terse and restrained by default due to its cramped format—into a new narrative arc. In Kick the Latch, though it contains a lot of Sonia’s original speech or a near approximation of it, I shaped and organized and sometimes reimagined and rewrote the source material, which is expansive and wandering in the typical way of casual speech.

ZD: Your trust in details that might otherwise pass for mundane or unworthy—such as: “My cousins have been here and I was shampooing carpets before that.”—enable entry into the realm of the private. This reminds me of Sonia and a horse like Dark Side, who was on the kill truck, on the way to the slaughterhouse. Sonia sees something in Dark Side, and she trains him into a champion. In her own way, Sonia is a kind of an artist, sculpting the horses under her care. What parallels do you observe between the practice of writing and horse training?

KS: I think both probably favor the ability to be quiet and pay attention.

ZD: I want to ask you about the gaps in your dialogue with Sonia. In the afterword, you mention that interviews occurred in 2018, 2020, and 2022. What was the status of the project during those intervals?

KS: After our first conversation in October 2018, I transcribed the recording and started working with it. I emailed a short sample—“Racetrackers”—to Sonia in spring 2019. She wrote back: she was excited I was working on something, but she couldn’t open the files. I tried to arrange a phone call but didn’t hear from her; I later learned she was taking care of ill family members at this time. I continued to think about the project but put it on the back burner awhile. Aug 9 and The Dominant Animal were coming out, and I was working on other things.

In spring 2020, I returned to it, finished a draft using the material I had—still from that single conversation—and sent it to my agent in the fall, but we both felt it wasn’t right yet. I emailed Sonia again and was able to set up a phone call with her. We spoke for several hours in October, and I recorded the call with her permission. I had a list of notes and questions for her, things I wanted to know more about.

I recorded another call with her after that, then transcribed both of those and revised the manuscript to include the new material. I mailed her a copy of my draft in February 2021. She sent me some notes, we had another phone conversation, and I revised the draft again.

We had one last recorded call in March 2021. I did an overhaul of the manuscript after that. I finished the final draft at the end of April, then mailed it to her to make sure I had her blessing before sending it to publishers.

ZD: Did it take a long time to land on the form of Kick the Latch—its division into twelve sections, the order of its anecdotes, the stark appearance of the text amid the negative space of the page?

KS: Yes: I wrote many drafts of the individual chapters and tried many arrangements of the chapters into sections. I shuffled and reshuffled section and chapter order. I had maybe two dozen sections at one point but landed on twelve in the end because it felt right, and because a thoroughbred race—at longest—is twelve furlongs.

ZD: Your conversations with Sonia occurred in person and over the phone. How did the mode of interview affect the conversation? Did you prefer one to the other?

KS: It’s easier to communicate nonverbally in person, of course—to show you’re listening, to show interest without saying anything. It was easier to meet Sonia in person, I imagine, than to’ve tried to do it over the phone. But the phone calls were fun and more conversational than our first meeting—I was asking more questions, we were catching up. I mostly listened during our first meeting.

ZD: This interview is taking place over email. What is that experience like for you? Generally speaking, do you prefer asking questions or answering them?

KS: I’m generally uncomfortable answering interview questions—I’m wary of opinions, especially regarding writing—and prefer an email format to a call because I never feel like I can think of what I want to say on the spot. I’m sort of distrustful of my speaking self. The imprecision of speech makes me a little sick if it’s being recorded for print. I don’t prefer asking questions or answering them—I prefer listening.

ZD: What have Aug 9—Fog, Kick the Latch, and The Dominant Animal taught you about the process of editing? How have you evolved as an editor of your own work across these projects?

KS: In some ways I think editing is like anything else—proficiency comes with practice—but there’s also something about it—and about writing in general—that exists outside the idea of proficiency. Even a good editor misses opportunities. It’s maddening. I guess that’s why I like it.

ZD: The Dominant Animal is dedicated to your dog Ruby. Sonia’s life was dedicated to horses. In Kick the Latch, we experience, vividly, the humanness and humaneness of animals—at times, in severe contrast to the bestial behavior of people in the book. As Sonia says at one point, “That’s why I always say my horse raised me.” Can you talk about your relationship to animals and what they’ve meant to you as both a person and an artist?

KS: I’ve never liked what “humane” and “bestial” are typically meant to imply—that humans are essentially kind, merciful, compassionate, and nonhuman animals are essentially brutal, depraved, non-thinking. I dedicated the story collection to my dog because for fifteen years she was my constant companion while I wrote, and because the title of the story for which the collection is named came from a line about her that was eventually cut from the draft, and because she died around the time I finished the book. The lines that were cut were about the discomfort I often felt about having a pet—this little creature who’s dependent on me by human design, whose physical attributes have been sexually engineered by us to suit our whims, and who I can pick up and lift into the air whether she wants me to or not. I’m not sure how articulate I can be about what animals mean to me except to say that they occupy a very large part of my thinking and writing, and that I’m always looking for them on the ground, in trees, in the sky.

ZD: At one point in the book, Sonia says, “They say horse racing is cruel, but there’s more cases of cruelty with backyard stable people.” How did your views about horse racing change—or did they change—after speaking with Sonia?

KS: I knew about the cruelties of horse racing before I started working on the book—but I’ve also loved going to the races since I was a kid. This tension is probably part of my interest in the subject. It was interesting to hear Sonia’s perspective: here’s someone who’s attuned to the animals, connected to them, who treats them with care and respect. She obviously feels disgust, indignity for the brutal way they’re sometimes treated. Yet she spent a good part of her life in this world. It’s complicated—a lot of people involved in horse racing just want to be near the horses, caring for them, looking out for them.

ZD: Kick the Latch also accentuates power structures. We notice their existence in the horse racing community—between owner, jockey, trainer, groom—between men and women, and in Sonia’s second career as a correctional officer. I’m curious about the power dynamic that existed between you and Sonia. How much scope did Sonia give you to shape her narrative? Did this dynamic change over time? Do you regard Sonia as co-author, as subject, or as something or someone else?

KS: I had no idea I would write this book when I first met Sonia. I told her I was a writer, that I wasn’t sure what form it would take if I did write something about her or whether I’d end up writing anything at all, but that I’d like to talk with her. She was interested and open from the beginning. I was a stranger, but she talked to me about her life in an intimate and generous way. After that conversation, I pictured the book as a continuation of the impulse behind Aug 9—Fog. But because Sonia is a living person, it was a more collaborative process. I asked what she thought about my drafts; I asked for her permission, her blessing—and I wouldn’t have proceeded if she hadn’t been happy.

ZD: On a related note, how do you perceive the power dynamic that exists between author and editor? Has this changed over the course of your career?

KS: I think there’s a lot of power and confidence to be gained in being able to acknowledge and embrace an editor’s improvement of your writing. When I was younger I might’ve felt more shame, more dejectedness about not getting it right on my own—or I might’ve been more quick to reject what was suggested to me. It depends on whether you trust and respect the person who’s editing you. I’m stubborn and I want to be able to do everything myself—I want and strive to be my own best editor—but a good editor will see things you can’t. You’ll say, “Oh—of course that’s better! Thank you!”

ZD: So much of Kick the Latch has to do with intimacy: its presence and its absence, and how the experience of each motivates behavior. When I think about your work, I think about the author behind it on a quest for connection. You inhabited the diary that formed the basis of Aug 9—Fog. You occupy the first-person “I” of Kick the Latch. In the case of a diary, its content is not intended to be read by anyone other than its author. In the case of Kick the Latch, Sonia told you her stories. Sonia, it seems, sought intimacy with you, with someone who would not only not be alienated by the language of her stories (“When I tell Jerry stories about the racetrack he doesn’t say much. It’s hard for people who haven’t been there to understand. There’s a particular language you pick up on the track.”) but also actually drawn to the particular language of her stories. For you, is writing, fundamentally, about achieving a particular language—a language that you can connect with in itself and one that is a means to connection with others?

KS: I do hope that language arranged in a particular way might provide some means of connection—with a reader or with myself—but I’m also aware of how difficult it can be to communicate with other people, or even to articulate something to yourself. I don’t think it’s possible to have something specific you want to say in a piece of writing and to say it in a way that everyone will understand you. Better, maybe, to abandon that idea and find delight in whatever you say instead—and in the ways it might be interpreted by someone else.

Zach Davidson is a senior editor of NOON and a contributing editor to BOMB. His fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

More Interviews