Let Us Now Praise Giant Men | A Song for Manute Bol

sports

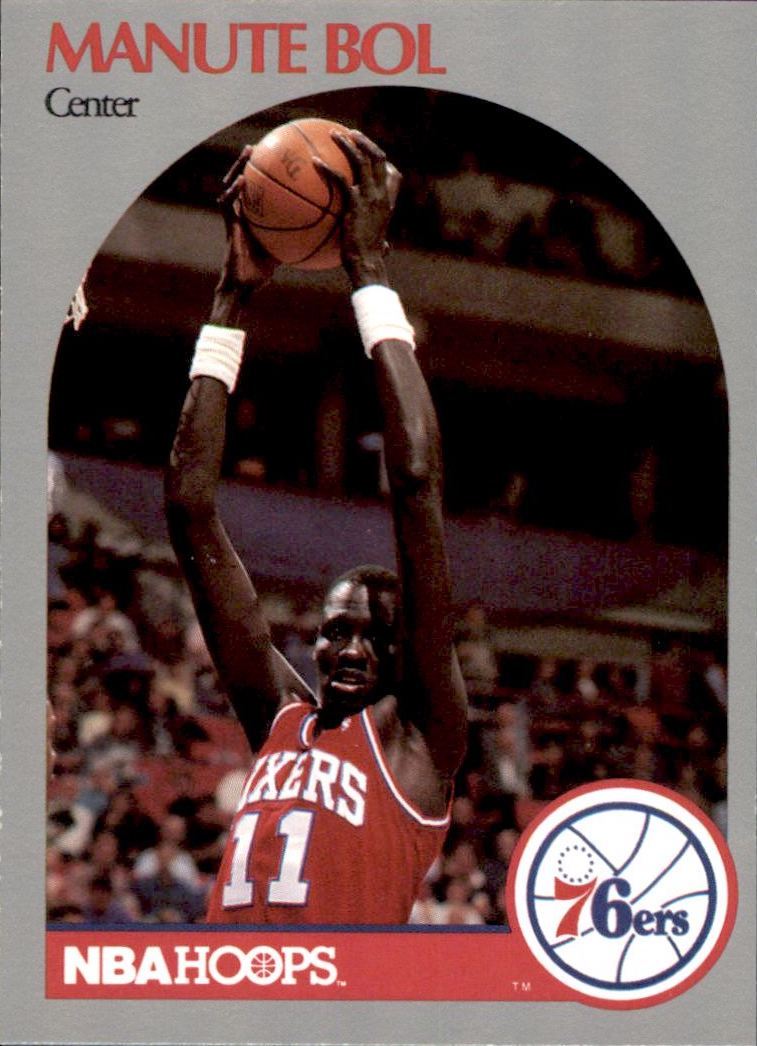

Let Us Now Praise Giant Men is a basketball column by Liam Baranauskas. This inaugural edition is about a game in which seven-foot-seven Manute Bol hit six three-pointers.

The song I sing my son to sleep with every night goes like this: Abiyoyo, Abiyoyo, Abiyoyo, bi-yo-yo, bi-yo-yo, Abiyoyo, bi-yo-yo, bi-yo-yo. It’s a Pete Seeger song, from a retelling of a South African folktale. Abiyoyo is the name of a giant who terrorizes a village. He steals sheep.

In the story, a boy and his father confront the giant. They’re outcasts, made to live on the edge of town, mostly because they’re annoying; the boy won’t stop badly playing the ukulele, and the father keeps making everyone’s stuff disappear with his magic wand. The song I sing to my son is the one the boy sings to the giant, to lull him to the ground.

The giant had never heard a song about himself before, the story goes, and he started to dance.

Here is something that I do not think is up for debate: if you are a child, you are probably very small. This also means that everything around you is, yes, very large. The world is made for adults, and we are giants, monstrous and fascinating, our power to be feared and aspired to. I think this is why kids a little older than my son (he’s almost two) gravitate toward dinosaurs, creatures so huge that buildings don’t fit them and so capricious they could eat up mom or dad without a second thought.

When Abiyoyo’s furious dancing makes him fall, the father waves his magic wand and—zoop zoop!—makes him disappear.

I sing until my son is on the cusp of sleep. When his eyes finally close, the large world around him will fall away and he will enter one exactly his size. There will be just him. In sleep he will be the giant as well as the boy. Remember, when you’re a child, one way to disappear is to close your eyes.

![]()

A sportswriter did some cocktail-napkin math once and found that men who are seven feet tall have historically had a seventeen percent chance to play in the NBA. If you’re, say, 6’7”, making it to the pros still requires being blessed with fast-twitch muscles like tightly coiled springs, an unfaltering work ethic, the dexterity of a juggler, the confidence of a flimflam artist, and enough luck for seven lifetimes. A seven footer just needs to be better than six other tall guys.

It all rings true if you grew up watching basketball when I did, in the late 80s and early 90s. Back then, there were, of course, giants on the court who were terrifically skilled players—Hakeem Olajuwon and his balletic, wonderfully named “Dream Shake,” Yao Ming (all seven feet, six inches of him) and his surprising grace. David Robinson, Patrick Ewing. Even Shaq, for all his brutishness, wasn’t simply bigger and stronger than everyone else; he used his body as precisely and decisively as a carpenter hammering a nail, forcing it where he wanted it to go, resistance be damned.

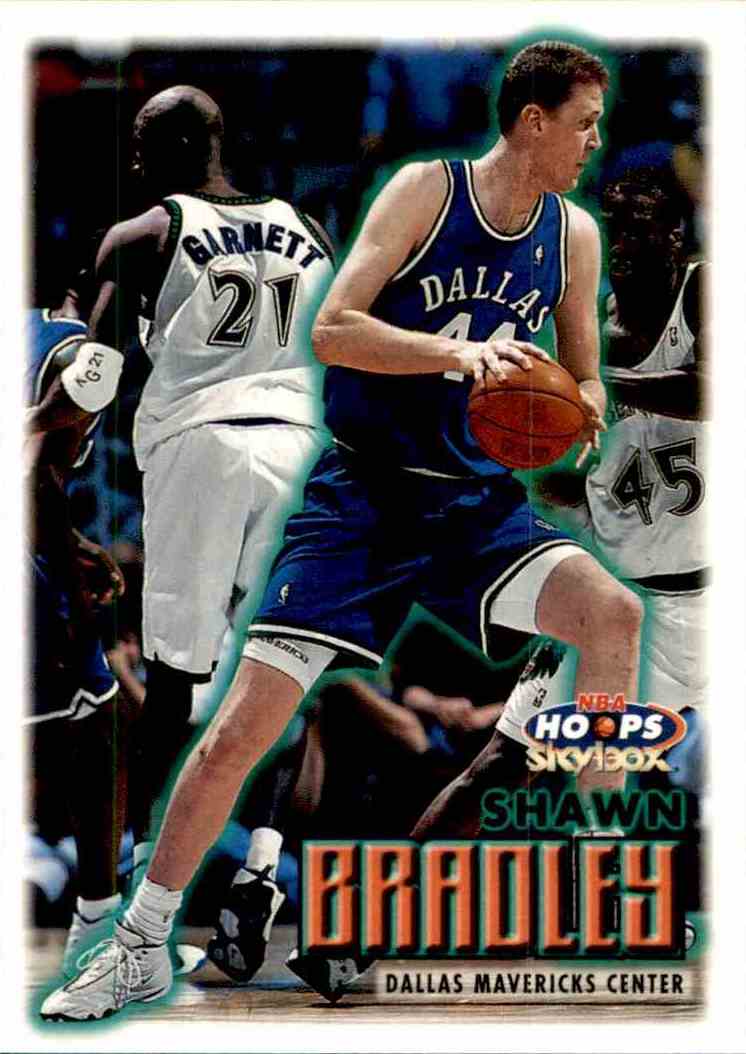

But the NBA I grew up with also contained clods, doofuses, goons, yobs, and all manner of uncoordinated and very tall losers who did not really seem to like basketball very much. They played like they wanted a cigarette. You can see them in the backgrounds of old highlight videos, futilely waving their arms like inflatable tube men promoting a car wash while Michael Jordan, tongue out, floats past them in slow motion. Their names sound like video game bosses: Luc Longley (yes), the Collins Twins, Yinka Dare. There was Greg Ostertag and Shawn Bradley and Uwe Blab.

But the NBA I grew up with also contained clods, doofuses, goons, yobs, and all manner of uncoordinated and very tall losers who did not really seem to like basketball very much. They played like they wanted a cigarette. You can see them in the backgrounds of old highlight videos, futilely waving their arms like inflatable tube men promoting a car wash while Michael Jordan, tongue out, floats past them in slow motion. Their names sound like video game bosses: Luc Longley (yes), the Collins Twins, Yinka Dare. There was Greg Ostertag and Shawn Bradley and Uwe Blab.

In the last few years, professional basketball has undergone a well-documented stylistic change. What’s now thought to be the best way to score points is shooting from beyond the three-point arc rather than getting close to the basket for an easier but less valuable shot. This is a matter of degrees, of course—players still dunk, make layups, and shoot short jumpers, but the balance has shifted. The result is, in many ways, a more aesthetically pleasing game, resembling the joga bonito era of Brazilian soccer. Teams pass quickly and frequently over wide swaths of court, their players whirl around each other with the dizzying, coordinated movements of Busby Berkeley choreography. And there’s a thrilling whiff of the paranormal to a long three-pointer, as if the ball is being guided to where it’s meant to go through some strange telekinesis, and the surprise and joy when it arrives seem to be shared by many of the best players, who skip and wink their way through games. Many of them, like Steph Curry or James Harden, are more or less normal-sized, around the height of your tall friend.

Of course, in a sport with a geometry that, more than any other, includes height, being big remains a legitimate and scarce asset. But today’s big men have to do more than their predecessors. They have to guard comparatively tiny opponents far from the basket. They have to shoot three-pointers themselves. They have to be able to dribble without falling down. A few play with such speed and artistry that it’s easy to forget that they are among the tallest people in the world. They are tall, but that is because they are basketball players. The oafs, the true giants, the ones who were on the court for their size alone, have all but disappeared. And as beautiful as today’s game is, this is a deep loss.

![]()

“No one roots for Goliath,” Wilt “The Stilt” Chamberlain once said. This was not, it seems, a simple comment about height, but about the supposed advantages height conferred on him. We learn early on to put ourselves in David’s place, because it’s with courage and skill that we’re meant to make our place in the world. Our outward size does not prove the size of our hearts. We don’t have it easy, not like the giants. That’s what we’ve always been told.

There’s a character in the video game Street Fighter II named Zangief, a Russian wrestler who’s twice the size of the other playable characters. Of course, choosing to play as Zangief is a sucker’s move. You’d be hard-pressed to find any legend or fairytale or story where the giant actually triumphs in the end. Ultimately, the giant exists to fall. To disappear.

Except. One of the developers who created Street Fighter II apparently loved playing as Zangief, to the point that other members of the team believed he was secretly trying to improve the character’s attributes. The result, according to an oral history of the game, was that his feedback during testing, even about non-leviathan matters, wasn’t taken seriously. His desire to see the giant win—his desire to be the giant—rendered him abnormal, his opinions worthless.

The NCAA made dunking illegal when Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was in college, on the grounds that it gave him an unfair advantage. No one roots for Goliath.

![]()

On March 3, 1993, the Philadelphia 76ers played the Phoenix Suns, and 7’7” Manute Bol—an ungainly stick figure remarkable for both palpable dignity and a stunning lack of coordination—hit six three-pointers for the 76ers in the second half. Bol was no forerunner to today’s sweet-shooting big men; he had grown up playing soccer in southern Sudan and his shooting motion was two handed, from behind his head, as if throwing a soccer ball in from the sideline, or a life preserver into the wind at someone drowning. In the highlights on YouTube, the announcers’ disbelieving laughter as each shot goes in is laced with ridicule. The recording is from a grainy VHS, and the other players on the court look like children. Bol looks like Slender Man.

This, to me, is beautiful. There was no reason for Bol, who before that night had not hit a three-pointer in over two years, to shoot from behind the arc twelve times, but he did. For his career, Bol hit 21% of his three-pointers; he hit half in this game. After two consecutive misses, one an egregious airball, the color commentator wearily says, “That’s enough.” Bol cans his next three shots.

This was the giant’s triumph. He was not stealing sheep like Abiyoyo, but instead sat down at the table, spread his napkin neatly on his lap, and used the correct fork for the salad and the correct fork for the fish.

The story of Abiyoyo doesn’t explain where Abiyoyo goes when he disappears. He’s simply gone, turned—zoop zoop!—to white space on the page of the storybook. The villagers carry the boy and his father off on their shoulders, telling them that they’re welcome to return to town. They can even bring the ukulele and magic wand. They all sing. Abiyoyo, Abiyoyo, Abiyoyo, bi-yo-yo, bi-yo-yo.

You and I will never play professional basketball. We will never be carried off on anyone’s shoulders in triumph. We will never boycott an awards ceremony or surreptitiously hand off a flash drive with classified information at a busy train station, or live out most of our childish dreams. These are rarified heavens accessible to the very few, and this is what makes the oversized lummoxes who once played professional basketball figures of hope. Their presence on the court was a fluke, and their beautiful bumbling made them more like us than the players who were more like us, mortals encroaching on the terrain of the gods through accidents of anatomy.

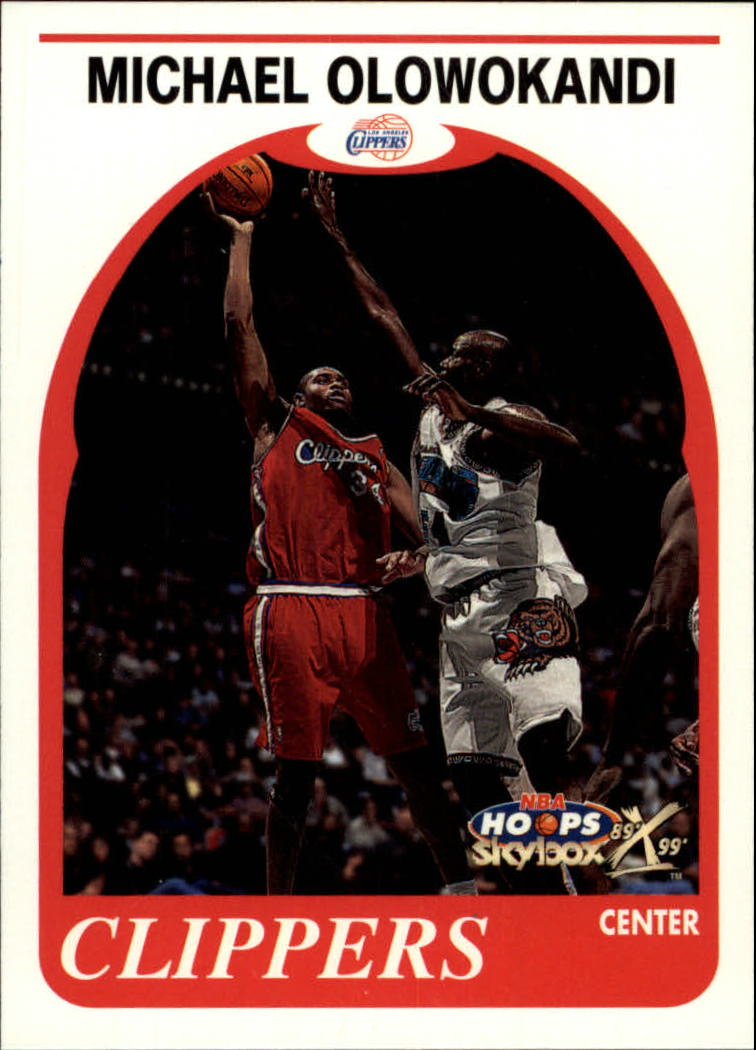

I believe Mark Eaton’s parents called him on Sunday evenings and offered encouragement that did not quite veil their disappointment. I believe Michael Olowokandi wakes up on Monday morning with his stomach a tight ball at the prospect of five coming days at a job that he hates. Todd McCullough probably wastes too much time on his phone, and it, too, is no more or less unfulfilling than the time wasted by someone regular-sized. I do not think these things are true of, say, Allen Iverson.

I believe Mark Eaton’s parents called him on Sunday evenings and offered encouragement that did not quite veil their disappointment. I believe Michael Olowokandi wakes up on Monday morning with his stomach a tight ball at the prospect of five coming days at a job that he hates. Todd McCullough probably wastes too much time on his phone, and it, too, is no more or less unfulfilling than the time wasted by someone regular-sized. I do not think these things are true of, say, Allen Iverson.

I think about what Manute Bol must have felt when he hit those unlikely three-pointers. From the court, he would not have been able to hear the television announcers making fun of him. He would have only heard his name over the public address system, Manute Bol, Manute Bol, Manute Bol. Abiyoyo, bi-yo-yo, bi-yo-yo.

Someday, my son will realize that giants do not exist, and that is the day he will also become one of us. I hope he knows the joy of dancing to a song about himself before he disappears.

Liam Baranauskas is a writer from Philadelphia. He is currently working on a novel.

More sports