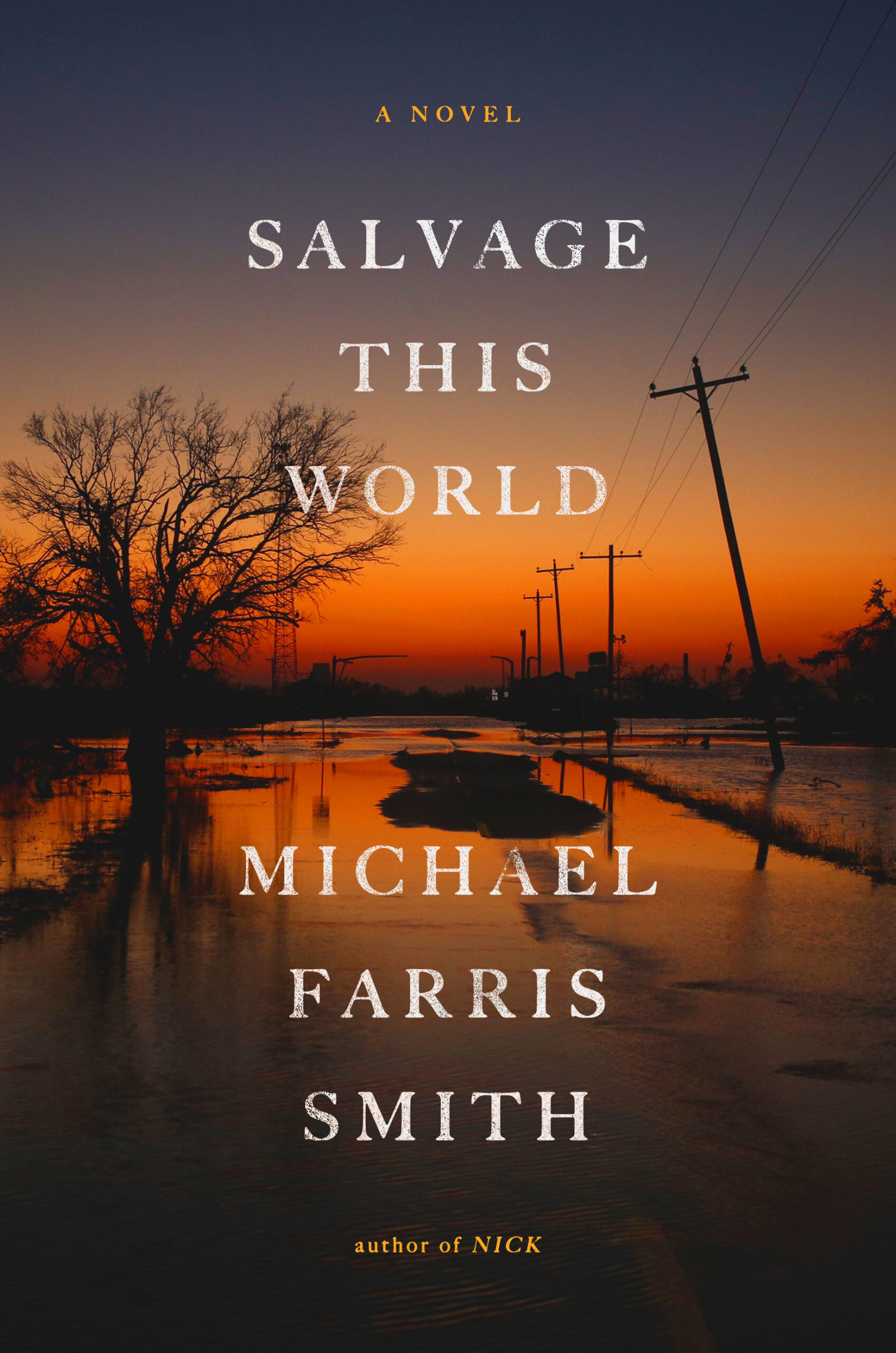

Excerpt from Salvage This World, a New Novel by Michael Farris Smith

Web Exclusives

The following is an excerpt from Michael Farris Smith’s Salvage This World, a novel that “journeys into the heart of a region growing darker and less forgiving, and asks how we keep going in a land where God has fled,” according to the book’s publisher. The novel is out next week from Little, Brown.

She stood bathed in twilight, the dust in her hair and a kid on her hip and she stared at the approaching storm as if trying to figure how to wrangle the thunderheads and steer them to a distant and parched land where desperate souls would pay whatever ransom she demanded. The acres of sugar cane cut to nubs surrounding the house. A dry autumn turned into an unpredictable winter and then eleven days ago he left and she’d seen no one since. It was a mile walk along a dirt road that separated the acreage and another eight miles to walk to the nearest telephone but even if she wanted to bundle up and make it she wouldn’t know who to call. He was gone. And he had taken the car and the cigarettes and every dollar except for the stash she kept hidden beneath a floor plank in the closet. She had finished the last of the whiskey three nights before. The milk had run out yesterday.

Jessie stared at the storm and the wind began to blow and dustclouds rose like souls awakened and she listened to the wind and welcomed the sound of something else. She shifted the child from one hip to the other and pointed out at the lightning and said look at the light. See the light? One side of the sky was thick with stormclouds and the other side of the sky was wrapped in a rustred belt that bled into the horizon like an open wound and the child lifted his small hand and pointed at the light but it was not the lightning he saw but a gathering of headlights approaching in the distance. The thunder roared and the engines roared and she turned and ran for the house, setting the child down on the porch and hurrying for the bedroom, her footfalls hard against the floorboards and her breath in quick sucks as she took the pistol from beneath the mattress and grabbed the set of keys from the dresser drawer that he had always told her to grab if she had to make a run for it and then she hustled out and scooped up the child. The headlights growing closer and splitting the dusk as she hurried around the house and along the beaten trail through the high grass that led into the woods. She ran and the child bounced in her arms and she had just reached the edge of the woods when she looked back to see the vehicles skid to a stop in front of the house, a pale and powdery cloud rising around them. She heard the engines cut and the doors slam behind her and then she heard the shouts coming in her direction as the last of twilight seeped into the earth.

They called out as they chased her into the woods and the child squeezed her neck and held on but did not cry as she ran. She had gone far into these woods before but never far enough to know if there was anything on the other side and she was seized by the thought that she may run over the edge of the earth and that she and the child would plummet soundlessly into nothing. That thought was interrupted when a shotgun fired into the night, its echo ringing through the trees. She pushed harder. Squeezing the child close to her chest. Praying not to run over the edge or if there was such a thing praying that her fall would be brief and painless. Another shotgun blast. And then another. She knew then they were looking for him. She knew there was a fine damn reason he had never returned. She knew she and the child could never go back to the house. And she knew she would have to keep running.

![]()

They shivered through the night. Jessie unbuttoned her flannel shirt and held Jace against her skin and wrapped the shirt around them both but it did not stop the shaking. He cried some. Little whimpers of discomfort. Little whimpers of hunger. She sat on a pile of leaves with her back against a white oak and held him tight. Rocked a little. Hummed and sometimes sang and she kept promising that everything was going to be all right. The boy slept in increments, the ragged sleep of distress and discomfort. An owl hooted. Nightbirds sang. Deer moved in the dark and the sound of their creeping sounded like monsters in wait.

She nodded in and out of sleep. When her eyes fell heavy she imagined strong arms and strong hands reaching for her though the dark, prying the child from her grasp and she would wake with a jerk to find herself squeezing the child so tightly he was struggling for freedom. She would stroke the back of his head and coax him back to sleep and her eyes stayed opened wide, watching the woods and watching for the arms and hands that approached in her dreams but then closing them again.

Finally there was light. She rubbed her eyes. Felt the warmth of the child’s skin against her own. She did not want to wake him so she sat there and watched the morning come. Listened to the chirps and whistles and the movement of the early creatures. The child lifted his head and coughed. Opened his eyes and looked with question at his mother.

She kissed the boy on top of his head and said it’s all right. It’s all right. She then tucked the empty pistol into the back of her pants and she started them walking south, believing if she kept walking south they would run into Delcambre. Amidst the trees she would stop and listen for the hum of a highway. Set the boy down and rest a minute. Listen. Then he would cry to be carried again and she would tell him to hold on. Hush a second. But he was not concerned and he cried harder and made little mad fists and she would pick him up and start again.

In an hour she came to a clearing and the earth grew soft and heavy. The damp ground sucked at her feet and she set the child down and retied the laces on her boots. He wobbled and plopped down on his behind, a smack as his ass hit the wet ground. He screamed. Something different now than toddler whimpers. He screamed and shook and slapped at his own legs, redfaced and releasing as much anger as his little body could muster. And she propped her hands on her hips and looked down at him and said let it out. Let it all out, boy.

When he was done she reached down and helped him to his feet. The back of his pants muddy. He stood next to her and they both looked out across the marshland. Cranes stood on stumps. A flock of blackbirds rose from a clutter of young cypress and scattered across the low sky. The sun sat on the horizon and lathered the marsh in gold. It seemed beautiful to her in a way she had not expected.

But there was no time to admire. The child was now wet. And hungry and cold. She was hungry and cold. She didn’t know where they were but she knew there was highway somewhere.

![]()

They circled around the edge of the marsh for at least an hour. Crossed into another wood where the trees thinned. The sun rose higher into a blue and cloudless sky. Their pace had slowed and the child slept with his head on his mother’s shoulder. The pistol was cold and hard against the small of her back and every now and then she touched the pocket of her jeans, feeling the keys and making sure she had grabbed them and it was not part of a some hurried dream.

First she saw the smoke and she followed it until she was close enough to smell it. She came to the edge of the woods and stopped. Hid herself behind a tree. Saw the small cabin with the smoke rising from its chimney and a trailer next to it. A truck sat unevenly, propped up by a jack. A front tire missing. The hood raised. Behind the truck a hatchback sat running and the driver’s door was open. A cloud of exhaust from the tailpipe as the heat met the cold.

A woman stood on the cabin porch with a lit cigarette. Then another woman joined her. She held a shovel and she leaned it against the doorframe. They both wore denim jackets with collars pushed up around their necks. Both stood with their hips propped while they smoked. They talked between inhales and exhales in one and two word sentences. When they were done smoking they flicked the butts into the dirt and one of them yelled out toward the trailer. Come on. We got shit to do.

The women then stepped back inside the cabin, leaving the door open.

Jesse sprinted from the woods, the child waking with the sudden jolt and he let out a cry that she didn’t acknowledge as she darted between old tires and a pile of firewood and a smoldering heap of trash and then she heard the growl as a wolf on a chain rose from slumber and lurched at her backside with its bonewhite fangs only to be held fast by a chain. She screamed and the wolf yelped but she didn’t slow down, making it to the hatchback and hopping in just as a man in coveralls emerged from the trailer holding a coffee mug. He sipped and watched dumbeyed before realizing it was a stranger in the car. A stranger holding a child. He hollered and the two women came from the cabin and the three of them came down steps and ran for the hatchback as Jesse shifted into reverse, the car door open and flapping like a wing and then slamming shut when she hit the brakes, shifted into drive and stomped the gas, the tires spinning and the three of them trying to corral the hatchback like some untamed animal and as the car raced away from their cries a coffee mug crashed on the hood as if dropped from heaven, just as the tires caught firm on the gravel road.

Michael Farris Smith is the author of the novels Salvage This World, Nick, Blackwood, The Fighter, and Desperation Road. He has also written feature-film adaptations of his novels Desperation Road and The Fighter, retitled for the screen as Rumble Through the Dark. He lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

More Web Exclusives