Animated Profundity

Reviews

By Ryan Ridge

My first introduction to the awesome power of cartoons arrived in 1995. I was sixteen. It was fall break, and with the day off school, I’d scored two hits of acid from an acquaintance named Wayne. “Be careful,” Wayne warned as I pressed a tab to my tongue at 10 a.m., “they’re double-dipped. One is more than enough.” A likely story, I thought as I handed him a twenty, figuring it was only a ruse to overcharge. Later, as my head began humming in the park, I sat in the grass, peering through the cigarette cellophane containing the other dose. I laughed as I realized the acid had a little cartoon bomb on it. The bomb’s wick was lit, and above it, a fiery-red caption read bonk! Indeed. After a failed campaign to enlist one of my friends to eat the other blotter, I gobbled it myself, dumbly ignoring Wayne’s warning. My friends were already tripping on something else that day: Jesus Christ. They’d each eaten a tab of LSD with Christ’s visage on it. We were Catholics then, and my friends claimed the Jesus acid would produce a more spiritual trip. Right, I thought, as my vision suddenly went sideways. Nearby, a skinny branch from a sugar maple reached out like a stranger’s hand, waving for a moment before it shot me a middle finger. “Guys,” I announced. “I don’t feel so good. I’m going home.”

Once home, I lay on my back on the linoleum bathroom floor, watching bizarre flowers blooming and mutating into classic movie monsters in the stucco ceiling as the afternoon turned into evening in the skylight above. Then, my mom loomed over me, glaring down after a day at work. “You look terrible,” she said. “You’re green.” I covered my face with my hands and confessed that I was super high. She returned and handed me a cordless phone. The guy from Poison Control asked what I’d taken. I knew better than to tell him about the acid, so I said I’d just smoked some weed. “How many joints?” he asked. I told him we never smoked joints and that we preferred bong hits. “How many bong hits did you take?” he asked. In my mangled mind, I ran the numbers. I figured ten bong rips equaled a hit of acid, so two hits then meant twenty bong rips, but then I remembered the blotters were double-dipped and thus multiplied my estimate. “Forty,” I said. “You took forty bong hits?” he said, sighing. “Put your mother back on the phone.” After they hung up, my mom relayed the diagnosis: “He said you’d be fine. He said you should lie on the couch with a cold washcloth on your head and watch cartoons. You should also drink a lot of water, he said.” So I did, watching a Hanna-Barbera marathon until my shattered sense of self slowly returned many hours later. As I started to come down, I remember thinking, These cartoons are fucking profound!

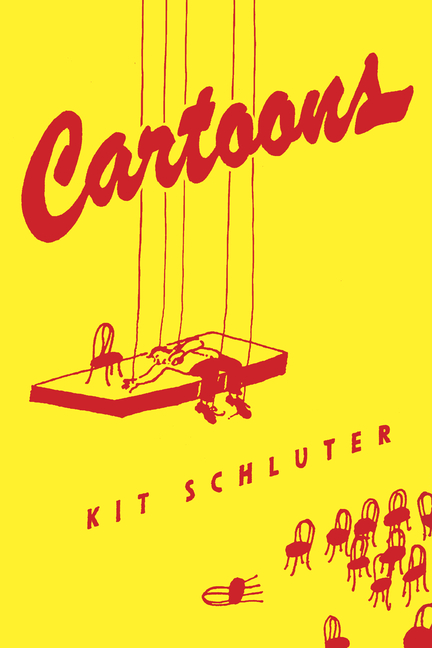

I’d forgotten this ludicrous memory for nearly thirty years, but it roared back as I read Kit Schluter’s remarkable collection of absurdist fiction, Cartoons. Nothing is as it seems, and the surreal permeates Schluter’s hilarious and hallucinatory tales. In terms of a vibe, imagine if Borges, Richard Brautigan, and Aimee Bender went on a tequila binge and, in the process, rewrote and updated Aesop’s fables; then you might get an idea of what Schluter is up to in these thirty-odd stories accompanied by fourteen equally compelling illustrations that could be described as Raymond Pettibon-esque. While the stories range from short (the longest is fifteen pages) to very short (a single sentence), almost every piece warrants an immediate reread to marvel at the tale’s unorthodox turns. Just when you think a scene will zig, it zags. When you assume a beat will move linearly to the next, Schluter doubles back and offers a meta-commentary on the possible paths the piece might take. We never arrive in proximity to the predictable. Schluter always keeps us guessing, making Cartoons such a fun trip.

The collection kicks off with an allegorical preface. While wandering through the Mexico City night, the narrator encounters an open sewer cap teeming with cockroaches. A disembodied voice cuts through the night and challenges him to embrace the cockroach, warning of the perils of rejecting it. This encounter sparks a profound change in the narrator’s perspective, as he now sees the cockroach’s “superiority to the human” in its “lack of sentimentality” and “liquid manner of striding in unison.” Like the cockroach, the subsequent stories possess a “liquid manner” of movement. Like any great writer, Schluter isn’t afraid to risk sentimentality, and due to his angular approach, he never slips into the sanguine.

Indeed, Schluter excels when he interrogates the past. In “30th Birthday Story,” a fictional Kit Schluter spends a quiet celebratory afternoon reading, writing, and chilling with his dog, Xochi, until he’s interrupted by a knock at the door where he discovers three different versions of his past self: a baby Kit, a ten-year-old Kit, and a twenty-year-old Kit. The scene devolves into a controlled chaos that offers poignant commentary on aging and identity thanks to Xochi’s reaction to the various Kits. The story reads like a crafty nod to Borges’s “Borges and I.” It asks: (1) What separates the artist from the self? and (2) Can a person transcend their past?

With echoes of Arthur Bradford’s iconic Dogwalker or Brad Watson’s equally excellent Last Days of the Dog-Men, dogs are a recurring theme throughout Cartoons. The short-short “Dog Person” begins, “Today I sat in the shallow sea trying to pet the foam of the waves, as if it were a dog.” Two sentences later, the story concludes on a graceful note with the narrator unable to harness the sea: “For this I loved the foam, and I reached toward it with ever greater obstination.” Similarly, “Civil Discourse” unfolds as a dialogue between the narrator and his dog wherein they pontificate about the flawed nature of communication between species—but in typical Schluter fashion, the roles get reversed. After the dog destroys the narrator’s property, she speaks shrewd aphorisms, and the narrator responds with a primal scream. It’s a perfect bit of defamiliarization.

In addition to defamiliarization, anthropomorphism is a primary apparatus in Schluter’s toolbox. Along the way, we encounter talking ants, cockroaches, crickets, lobsters, pencils, philosophical sloths, and even an umbrella on a self-improvement journey. Still, my favorite is the unhinged appliance we meet in “Handwritten Account of an Afternoon Spent Talking with the Microwave.” In the dialogue-driven piece, a metafictional Kit Schluter attempts to comfort the sad microwave with an old tweet that says Schluter is “unabashedly, pro-microwave.” But the skeptical microwave isn’t having it: “WE ALL KNOW THE CYNICAL HUMOR OF THE TWITTERVERSE . . . ! HOW CAN I BE SURE YOU WEREN’T SATIRIZING?” The circular conversation leaves Schluter rattled and longing for home and thus concludes with him stealing a car and driving from Mexico City to his hometown of Boston. As always, the story ends unexpectedly, with a trope turned upside down. Here, Schluter knows a writer can’t go home again, but he goes anyway.

In “Parable of the Perfect Translator,” perhaps the collection’s pièce de résistance, an itinerant translator strolls into a Paris café claiming to have produced a perfect French translation of Virgilio Piñera’s stories. On the surface, it seems to the skeptical students he meets that the translator has copied Piñera’s book by hand in Spanish, but upon closer inspection, it’s revealed that the words are somehow capable of translating themselves into French.

Story after story, Schluter suggests that the impossible is not simply possible but probable with the right eyes. Certain writers reaffirm reality in their prose. Others endorse the idea that a consensus certainty is an entirely unreal set of expectations and that there’s always more to it than we can ever account for. I prefer the latter of stylists, which is why Schluter’s work resonates so much with this reader. In a time when many writers speak in talking points and debate the sanctioned issues of the day on social media, Schluter seems content to retreat into the wilderness of his imagination and dream up what he calls his “little cartoons.” I’m again reminded of my teenage self, coming down from the double-dipped acid trip: these cartoons are fucking profound!

Ryan Ridge is the author of five chapbooks and five books, including the story collection New Bad News (Sarabande Books, 2020) and the poetry chapbook Ox (Alternating Current, 2021). His YA novel, Beyond Human, is due out in 2025 from Gibbs Smith, and his collaborative collection Climate Strange is forthcoming from Astrophil Press in 2026. An associate professor at Weber State University in Ogden, Utah, he codirects the creative writing program. He lives in Salt Lake City with the writer Ashley Marie Farmer and plays bass in the Snarlin’ Yarns (Dial Back Sound).

More Reviews