Birds Are Also Free to Walk

Reviews

By Gavin Thomson

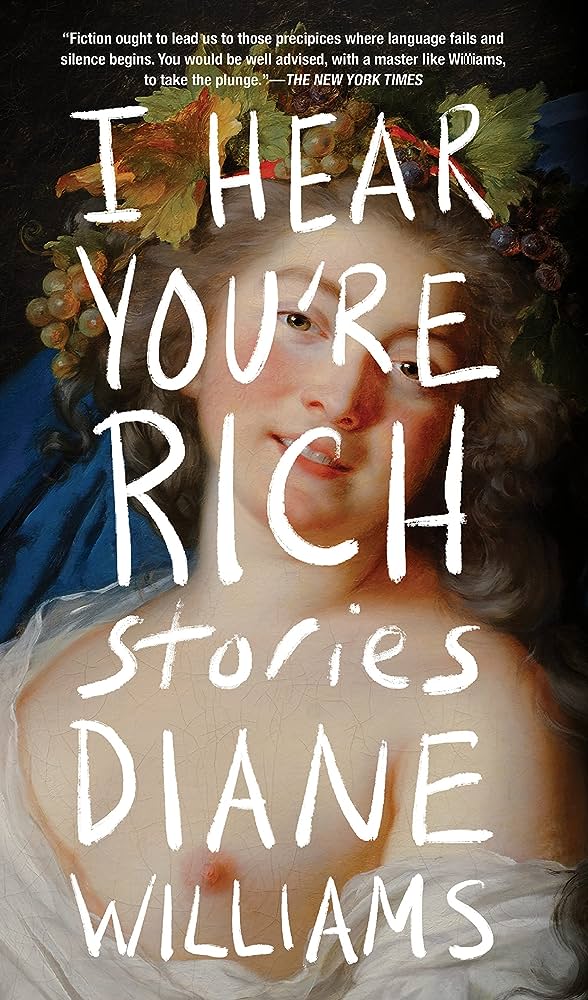

Who do we talk about when we talk about so-called flash fiction? Lydia Davis, mainly. But sometimes Diane Williams as well, at least for those in the know. Her latest collection of short stories, I Hear You’re Rich, contains thirty-three stories in only one-hundred-and-eleven-pages. Her second most recent collection, How High?—That High (2021), is almost identically built. Rarely does a story exceed four pages; the few that do are five. But it’s not only her writing that testifies to her unwavering fidelity to brevity: Williams is the founder and editor of a literary journal, NOON Annual, that publishes short stories of similar stature, including ones by Lydia Davis.

All this might suggest that both Williams the writer and Williams the editor are fans of concision and foes of its alternatives, averse to adjectives and other gimmicks and gewgaws, ink-constipated when writing but torrential with their edits, or otherwise evangelicals of the less-is-more denomination that for short fiction in America has remained in vogue since at least the mid-seventies, when Raymond Carver published a debut short story collection whose every word bore the DNA of Gordon Lish, apostle of minimalism. Williams, who has also worked with Lish, often gets labeled a minimalist. “Williams can do more with two sentences than what most writers can do with two-hundred-pages” is the sort of thing that critics have said about her work. Yet if she really is a minimalist, she’s not of the Carver type. “‘Gladly!’,” the eighth story in I Hear You’re Rich, begins, “He is a figure I once engaged with for years, amid scenes with nearly religious significance attached to them.” Carver would write something more like “We used to be in love.”

Williams’s sentences are syntactically flexible, spasmodic, surprising, artfully anal-retentive, and always drawing attention to themselves. Her stories dabble in metafiction and for the most part eschew dramatic dialogue, orienting details, rising stakes, dénouements, climactic epiphanies, and other fundamentals of traditional realist fiction. Characters aren’t always sketched-in, and settings are not always clear, including the decades during which stories take place—although the names of characters, the furniture and food, and the absence of smartphones and Wi-Fi offer clues. All her narrators sound more or less the same.

“‘Gladly!’” takes up a little over two pages and contains sixteen sentences in nearly as many paragraphs. The story, like others in the collection, is a sort of lyric in prose that moves not exactly linearly, nor especially logically, but rather like a somewhat disjointed daydream someone might enjoy while ambling along a path in a park—a daydream, to be sure, that’s been meticulously revised and condensed. The narrator of “‘Gladly!’” tells us that, just the other day while ambling along a path in a park, she happened to catch the figure she once engaged with for years. He smiled when he saw her, she tells us, yet when she reached him, “he was speechless and sour, and then he proceeded on his way headlong.” The narrator wished he’d asked her to come with him, but he hadn’t, so she held back. In the sixth sentence and paragraph of the story, she says—presumably referring to the figure—“But let us leave a famous man for a moment.” Yet she never does return to him. (Perhaps by leaving him behind in her story she takes revenge on him for having left her behind at the park?) Continuing along the path, she spotted a boy picking up handfuls of nuts that she thought were meant for squirrels and “inspecting the ground and most efficiently scavenging, stuffing his pockets, and repeatedly patting his large, jammed pockets.” The story ends:

He’ll be known later in life for his gluttony or his enterprise.

What am I—I wonder, dear god—now best known for?

“‘Gladly!’” is not the only story in I Hear You’re Rich that appeals to God for answers. Nor is it the only story that ends with a question left unanswered. The skinny collection is stuffed with all sorts of questions. From “Tom’s Fine”:

Am I still fair and worthy?

From “Mother of Nature”:

Could there be a speck of my original self anywhere?—that I have left behind. God, and if I have forgotten about it, can it save me?

From “Nancy’s Victory”:

She saw a small swatch of pink and supposed a sunset was out there and thought, What can that knockout pink do for me?

From “We Had a Lot of Fun Dancing”:

Am I qualified for my reward?

From “Everything Is Wonder”:

It is sad to ask, please don’t ask—but what is the measure of this wife’s utility, character, desirability?

Why did I ask?

Flip to a random page and you’ll likely find at least one question. The world for Williams’s characters is an endlessly baffling place—which might be another way of saying it’s endlessly interesting. “Doesn’t everyone want to learn,” says the narrator of “To What Beautiful End?,” “to explore—and to interpret the actions of people . . .” Well, no, unfortunately, but yes for most everyone in the collection. Appropriately, the title of the first story, “Oriel?,” is punctuated by a question mark, and the story itself is narrated by a pregnant woman so confused, when carrying a cake to a table at a party, that in seven sentences she asks eight questions:

But where best to look as I went forward? At the cake? Or at their face? This task takes common sense and balance as do all my others.

What to name our baby?—a sobriquet that means rich? Why not helper of humankind?—ardent or dawn? Deirdre, I like, but the name means sorrow—or Oriel?

(What’s going on? What should I do? What words should I chose? These are writerly questions.) Even sentences without question marks can be questions. “A Slew of Attractions” ends, “Where I am has an urban flavor and I ask myself to please make plain what my laughing matters are.”

If that’s an epiphany, it’s not of the climactic sort found in realist short stories by, for instance, Munro and Joyce. Rather than answering a question, the last line of “A Slew of Attractions” reveals a new question worth asking. Relentless curiosity is insatiable.

There is wisdom in relentless questioning and self-examining. There is also something immature. Philosophers and adolescents ask the most questions about the self (the latter about themselves). Philosophers and children ask the most questions about the world. The child is father of the man.

But man is no father of the child, if man can include the grandmother in “Zwhip-Zwhip.” She does not feel appreciated by her grandson, Neddie, a child, and “quite possibly she hates Neddie.” She watches Neddie play with an Easy Disk, and later, after dinner, she lingers in the kitchen, where she “prevails as a large body, slow walking, taking short strides from the table, thinking, Is it too much to ask for?—that the happiest, proudest day of my life will arrive?—when it is all I have ever aimed for.” It’s good for her sake that she doesn’t ask these questions aloud, because the sort of questions people ask expose the sort of people they are. Someone who asks who he is, for example, is someone who doesn’t know who he is. Someone who asks if he’s desirable is also someone who doesn’t know who he is. Variations of “Who am I?” and “Am I desirable?” recur throughout I Hear You’re Rich.

These questions inevitably overlap, particularly for those who place a lot of importance on sex, and Williams does. In I Hear You’re Rich (as well as in her previous books), her prose is often gleefully libidinal, as if she feels that she’s getting away with breaking a rule. Many characters are, scientifically speaking, horny. And there is some ado about dicks. “Keepsake” reads in its entirety:

I received a strong smooth cock that had nearly lifted itself out of itself—such a feat—but I could not keep it.

Williams’s second book, published in 1992, is titled Some Sexual Success Stories Plus Other Stories in Which God Might Choose to Appear. In I Hear You’re Rich, sex and God are also linked. From “Each Person To Her Paradise”:

When water gushed down his body when he rose from the tub, after he had bathed, that flow of water was a drumroll.

The god in this story is this man and I do not accuse him of anything. I could.

Williams was born in 1946 and studied at the University of Pennsylvania with Philip Roth. Williams’s themes also link her to Roth’s era, not so much to work by Roth himself but to work by Updike, Cheever, and Munro: realists invested in middle and upper-middle-class suburban life. Whether set in the suburbs or not, her work concerns what one critic has called “the annihilating demands of husbands, lovers, and children,” and what another has called “the dark underbelly of domestic life.” From “To What Beautiful End”:

We have tried out courtesy with one another for our safety’s sake, but I have no choice but to report danger. To whom? To him.

From “Seated Woman”:

Well, the atmosphere here is thick with dismissal and with so much I have done and do wrong.

Scenes take place in kitchens, sandboxes (for children), island homes, backyard pools with luncheon buffets, and the gift shop at a Vanderbilt mansion. Furniture and decorations include folding chairs, garden chaise lounges, thistles and wildflowers, armchairs, and carpets with carnations. Characters have names like Prissy, Dick, Polly, Marigold, and Gwen May. They eat biscuits and bread, endives and radishes, and something called a “big cheese-egg float.” Excluding the narrator of the titular story, they refrain from mentioning money at the dinner table.

There is often the threat of violence. Sometimes there is more than the threat of violence. In “Live a Little,” a woman named Ariadne (in Greek mythology, Ariadne was the daughter of Minos, King of Crete) is “stretched out on a garden chaise lounge” while her children are playing in the sandbox. Her husband “puts his hands on Ariadne’s throat when she speaks to him, pinching it just enough to snap a stem, but not enough to kill a whole plant.” She cries. Later in the story, the husband “takes into account their children,” and “he thinks that perhaps they are not so sad, for what do they lack?” Finally, a question with an answer: the children lack a father who doesn’t pinch their mother’s neck. The story ends with the children in the sandbox “stabbing at the sand.”

Birds fly in the sky. This is a known fact. Another thing birds fly through is I Hear You’re Rich. Doves, wood thrushes, blue jays, sparrows, and other birds appear throughout, typically as welcome guests. They aren’t fettered to marriages, mortgages, or money. They are free to fly.

They are also free to walk, which is an odd thing birds do, given the alternative, but they do it anyway. (Maybe they envy us? Probably not.) In “The Tune,” the narrator whistles along with a bird as it flies a bit beyond her, settles on a fence, and finally jumps to the ground at her feet. What follows is one of the most sexually ecstatic moments in I Hear You’re Rich and the closest Williams comes to ending a story with a neat and tidy climactic epiphany:

He was my creature briefly. We didn’t even vary the volume.

What I like best is taking my pleasure alongside somebody I barely know in such spasms.

Taking pleasure with someone you know well is another story, however. “Catalpa” is such a story. It’s about a married couple that have what so many people want. The husband is “a resource in great demand, thought by many women to be strong and protective.” The wife puts a stranger she passes at a public garden in mind of “the feminine ideal, a bit too pretty.” Theirs is an unhappy, loveless marriage. Yet the wife is in no hurry to “face the facts of her marriage,” the same way a “strolling pigeon” that she once followed “for more than several blocks” was in no hurry to get to wherever it had been going. While following that pigeon, the wife had wondered why it chose to walk rather than fly:

I will not disturb this bird!—she was thinking, even though it could not care less about her.

How far will it—she was guessing—can it go on this way?

Of course, what the wife is really thinking about here is herself, not the pigeon. How far can she go on this way is the real question on her mind. So why doesn’t she go ahead and ask it? Perhaps she knows the answer already and would prefer that she didn’t. Sometimes it’s better not to know.

Gavin Thomson writes fiction and nonfiction. He’s at work on his first novel.

More Reviews