Bloodlines | A Conversation with Kendra Allen

Interviews

By Halle Hill

Kendra Allen doesn’t waste time. Since her 2019 debut essay collection, When You Learn the Alphabet, she’s been at work constantly, making sense of the impossible. In the process, she’s positioned herself as a formidable writer who explores taboo truths with unflinching precision, sensitivity, and wit.

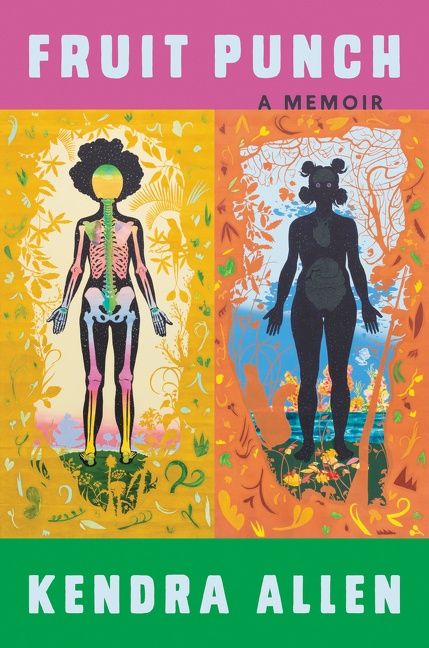

Now, Allen has published Fruit Punch, a hybrid memoir about coming of age in early 2000s Dallas, Texas. With her singular voice and stylistic range, Allen addresses issues of beauty, theology, trauma, Black identity, and childhood with bell-ringing clarity. She deftly brings the reader’s attention to the body and it’s generational truth: how it never lies, always knows, and always remembers.

I spoke with Allen in July over the phone on our lunch breaks while she was in residence at the Mastheads near the Berkshires in Massachusetts.

Halle Hill: Fruit Punch reads with a tightness and sense of wise distance, even if moments are emotionally charged. How long did it take you to write the collection? How did you approach editing?

Kendra Allen: I started thinking about the book at nineteen. Then I took a break and started again in my twenties. How many years is that? Five, six years? But I was thinking about it even before that. I would make little notes and draw stuff on the board. I remember drawing the neighborhood school on a map. It also had my mom’s job, my best friend’s house, my elementary and middle schools, the Texaco that we went to after school. Then slowly I began writing it. The book feels so strange now, because, over time, I probably took 64,000 words out of it. I’m really big on getting to the point, being succinct. I don’t want to read a 600-page anything ever in life. It can be the greatest book in the world, but I’m not gonna read it. After about 250 pages I’m done.

Taking those words out and doing those rewrites was hard. But, you know, that’s years of thinking and writing and process. And I should also say: accepting. I think I’m in the midst of processing that I wrote it now. But I knew that it was getting redundant. There were only so many ways I could say the same thing, which is kind of my problem in life. Or my problem with my parents.

Sometimes it felt as if nobody was listening. How can I make you get the point? And over the years, I became more and more comfortable with eliminating. I don’t really add that much stuff. I have a better sense of self-editing now.

I use a lot of repetition in my work intentionally. I think that repetition is when you’re trying a million ways for someone to just listen to you. But at some point, saying it over and over becomes insanity. I wrote it down, yelled about it, sent a letter. They still couldn’t hear me. At some point you think, I can’t say it no other way. This is as clear as I can be. Now you have to choose if you want to take it and hear it. I don’t know. But I do know I was very intentional in the way I went about it.

HH: What’s your process like? You seem like a prolific writer. How and where did you write Fruit Punch? What time of day do you write?

KA: For the duration of this book, I was living at home with my mom and my three cousins. And I saw so much of myself in them, especially the oldest one. I could just see how crowds make her nervous. How she notices things. Even when she’s at home with her mama, she always wanted to sit by me.

I took a lot of trips to Dairy Queen and wrote at night from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m. consistently. Sometimes my youngest cousin, Chloe, would ride with me to Dairy Queen. We listened to “No Manners” by Tiana Taylor a lot. That’s her song. I usually wrote with her next to me because she always wants to be where I am. I finished Fruit Punch in San Antonio.

As for how I write, I’m usually on the computer or the notes app on my phone. I write on the floor. I don’t handwrite anything because I can’t read my handwriting. I feel the need to keep writing and working on something due to this super-ambitious nature I have inside me.

HH: The narrator refers to her parents/parenting figures by names and nicknames (L.A., Doll, Banana, Miss Lady, etc.), rarely mom or dad. Many influential and shaping people get a nickname in this collection—I’m also thinking of [Heartbreak!]—which creates pitch-perfect, straightforward experiences of abandonment, distance, distrust, and/or disappointment. What was your process like in creating these spaces of longing and distance?

KA: So I’m trying to stop doing this thing where I discredit myself and act my decisions are only intuitive, not intentional. Part of that is true; they are absolutely intentional. And part of it is just like, that’s what comes out. But when I think about those big names, I’ve noticed it feels sad. I will call my mom “mom.” Loudly. I’ll repeat it so much and she won’t hear me. But If I say her government name or L.A., she turns around. So I wonder, Are you actually not listening to me for real, right? Do you hear what I’m saying? These nicknames were something I just started doing when I was younger.

My dad got his nickname because I was angry with him a lot when I was a teenager. For all the ways I thought he directly failed me, how he was treating me. He was something very disrespectful in my phone, like “sperm donor.” As a young person, I felt very distant from the roles I saw my parents in. I saw them as people. I didn’t see them like my mama and daddy. Of course, my mom was taking care of me. And I know she is my mom, and I do call her “mom.” But there’s this cognitive dissonance. Having these names is a defense mechanism.

When I started telling the truth to my family, they immediately put me back in a child’s place. That’s the only time I felt I was expected to be a child. But, in every other aspect of my life, I’m trying to protect the adults around me and myself. I’m trying to keep this distance between us. Because if I actually sit down and see the parenting skills that’s happening, it’s not right.

All my friends, all my family, they always say, I wish I had a mom like yours. I wish my relationship was like y’alls, you’re so, so close. Y’all have so much fun. My mom supports everything I do. She’s my biggest fan. But that’s only one side. So I have to use those names to create some distance to help me see clearly and create characters.

In writing this book, things kept coming out. I rewrote it so many times. It was me just forcing myself to admit that, you know, your mama is not your baby and I treated her like my baby. I tried to protect her, which is what I’ve been doing. From the day I found out that my daddy was cheating, I kept trying to cradle her.

I got a lot of firstborn son treatment. There was a lot of enmeshment. Parents think their children can’t see them in any other way than perfect. I’m a daughter, but then I also get treated like a reservoir. The nicknames helped me create barriers and boundaries. Everything in this book is about boundaries being broken. That is a constant repetitive theme: bodily autonomy boundaries, intellectual boundaries, physical boundaries, family boundaries, trust. You have to get some distance and float above it to see it.

HH: The body is so connected to our memories. And there’s something so evocative about the title Fruit Punch. There’s so much talk about bodies in your work—pleasure and blood, and violence against it. One of my favorite sections talks about your period and a sense of epigenetics and connection: “Sometimes there’s so much blood I think I’m dying. I think I’m bleeding for my entire bloodline. It comes out like fruit punch, clear and to the point, thick in a way that lets you know the components are maybe not good for you . . . There ain’t a month where cleaning the blood shedding out of me don’t feel like an omen.” What was it like for you to write about the body in a blunt sense?

KA: With the title, I was figuring out how to say something about the body. I’m talking about blood, right? Whether it’s bloodshed or bloodlines, in this case, I was thinking what can be the metaphor of that? My period. I talked about periods a lot. I like the thickness of it, how it feels in my hands. As a kid, I always just looked at it, watching it fall out of my body. I would think, what is that? It blows your mind. It reminded me how I drank a lot of Hawaiian Punch growing up. It’s the thickest and grossest juice to drink, but we drank it.

HH: This also makes me think of the essay “Coming of Age” and how masturbation is seen as a source of shame but also something that brings revelation. I’m thinking of some of the language that blew me away: “Sex and shame with myself is the only thing I got that I can control so I use my fingers to slide across the slit between my thighs and I’m sweating but even under the covers I feel watched as an involuntary tear pops once things feel good and I get scared and think I’ll turn into a puddle and then into a different person who can’t stop crying . . . And you hate yourself but when you do things well, you forget. And you love yourself, you really love yourself, for your brain mostly. And they look to you for all the answers, even though you only four years old.” The tension between pleasure and shame is really sharp.

KA: Thank you. I found the connection to be really strong. I took a whole essay out of the book; I have a whole section talking to my aunts and my mama. And they said they never had an orgasm. I don’t know why people have sex. I’m like, Bro, y’all got a lot of kids with many men. I remember when I was grown and asking them if they masturbated. And they looked at me like I was crazy. And I’m like, Y’all are not receiving pleasure from something that, in turn, is gonna make you end up pushing humans out of your body. But you didn’t enjoy any of it? How do we get here? We do it in silence—I think that’s the thing. Silence. And then we just suffer.

HH: Speaking of silence, do you feel like your book is quiet? I feel like it’s very internalized. It doesn’t scream at me. It’s to the point yet very, very subtle. Did you fear feeling silenced in writing it?

KA: Yeah, it’s quiet to me, for sure. And I think I wanted to reflect or mirror the quietness and aloneness of my head. You only think about the same things over and over. So I kind of wanted that feeling to come across.

Honestly, it’s kind of cliché to say, but this book is for me. Just so I can have evidence that I wasn’t making things up, or that I’m not crazy. I’m having all these puzzle pieces come together. And even making puzzles is a quiet thing when you’re doing it alone. You have to get it right to put it together. It’s quiet on the inside. But also it’s hardly quiet because, on the outside, I’m very loud.

HH: L.A. is one of the most fascinating, frustrating, and fully human people in Fruit Punch. I was struck by the way she moves from role to role. At one point, you refer to the relationship as a “sister wives”-type union. At other times, when she teaches you how to slow dance at the laundromat, drags you to church and choir practice with Miss Lady, or attempts to warn you about the perils of older boys and men, she briefly seems motherly, with glimmers of incredible, sensitive parenting. Other times—when she blows your phone up, takes in and cares for the family member who abuses you, accuses you of being sneaky, or has sex in the open in front of you—she seems unreliable and emotionally dangerous. How did you navigate presenting her flaws and humanity in balance?

KA: I think about this a lot because my mom is so good with kids. She really is. Kids love her. Even now she volunteers for a hotline for children who have been physically abused. And I can step back and understand that her inner child needs work. And I get why she takes care of me in the ways she does—because she was not protected herself. But then there’s this other dynamic of emotional abuse and emotional manipulation that confuses me.

I have to be honest about her because, as a child, I didn’t always want to see her as human. But now I do. I think she’s trying to do things differently with my nieces and nephews, but I see her in a whole sense. And there is still some residual grief. I still struggle today to tell somebody “I love you” back.

HH: One of my favorite sections in Fruit Punch is “After School Special.” It recounts the narrator’s admiration of an older, cooler, self-contained young woman named Reign. “I think she so pretty/because she always alone/Which make her calm in my mind/It aint got nothing to do with how she look, but how she hold her head.” Even though it’s very brief, “After School Special” shows your talent for blending genre and is one of Fruit Punch’s most honest, intimate, piercing moments. So many experiences in this collection speak directly to parentification: of young Black women taking care of themselves and others when they should be taken care of. In this memoir, while emotions are brimming and unflinching, they are never sentimental. How did you work to capture such a wide range in such a tight, smart, and unpretentious way?

KA: I thought about my mama a lot when I wrote this. Wherever my mama goes, she is herself. Wherever she goes, everybody knows her. People love me, but they really love my mama.

In relation to unpretentiousness, I had her as a model for that. She’s a person who is herself consistently with everyone she meets. She will chill and have a beer and hang out in the garage and treat everyone the same way regardless of title. So I worked from there.

For Reign, she knew the truth. But she also was hurting. She taught me a lot about being alone and with your thoughts. She struggled so much but she trusted herself. She would rather be with herself than be with people who are committed to misunderstanding her.

HH: Whose work did you look to for guidance? Was anyone walking beside you as you finished this book?

KA: Absolutely. I listened to a lot of music while writing. I make a lot of playlists, I have one I want to share here that I listened to while writing Fruit Punch. I listened to a lot of Brandy. For books, what comes to mind is Red at the Bone by Jaqueline Woodson. It’s a short, perfect novel.

HH: Did you think about audience at all when you were writing Fruit Punch? Were you concerned about how any of these themes would come across?

KA: I don’t think I was writing with an audience in mind. I’m proud of Fruit Punch. But also, Who’s gonna get it? I don’t know. I’m not interested in books that resolve or comfort the reader. I am not interested in completion or a perfect ending. It’s not a full circle thing for me. I know it doesn’t end on a good note. But, if I’ve learned anything from memoir, I’ve learned that nothing ever really resolves. I’ve never gotten over anything in my life. Being such a heavy reader of bell hooks helped me. She wrote dozens of memoirs. And she talks about similar things in a lot of those memoirs. It makes me think it’s endless—the work is endless.

One thing that helped me was standing in the power of my own words. I used to use a lot of lyrics in my work to help me navigate meaning. Some of the best feedback I ever received was from someone who said in a workshop, “You don’t need words from other artists to tell your story. You are a brilliant artist.”

Halle Hill is a writer from East Tennessee. She is a PEN/Dau Short Story Prize nominee, winner of the 2021 Crystal Wilkinson Creative Writing Prize, and a finalist for the 2021 ASME Award for Fiction. Her work is featured in Joyland, New Limestone Review, and Oxford American among others. Her debut collection, Good Women: Stories, will publish with Hub City Press in 2023.

More Interviews