Bob, Weave, Levitate | A Conversation with Lucas Schaefer

Interviews

By Greg Marshall

When I met my now husband, Lucas Schaefer, in the spring of 2011, he was still working out regularly at a boxing gym on North Lamar. More than just a place to get in shape, the boxing gym was the center of his social life. Most of his friends were from the gym, and they were an eclectic bunch. New to town, in my twenties, I admired just how Austin this all was: laidback, a little gritty.

I worked out at a kickboxing gym a few miles down the road on South Lamar, and by “worked out” I mean I rode a squeaky elliptical and listened to Elizabeth Strout novels. The kickboxing gym was not the center of my social life. There was something special about Lucas’s boxing gym—something that happened when, say, a musician, a judge, and an aspiring professional fighter worked the heavy bag side by side.

It’s no coincidence that Lucas’s favorite show to watch with his roommates, a couple from the gym, was Lockup and that early in our relationship we binged Jenji Kohan’s Orange Is the New Black. Prison, like Lucas’s boxing gym, was the rare place in American society where different kinds of people genuinely mixed together—and mixed it up. “Like Kohan, I’m a writer curious about the country’s intense racial and economic segregation and the uncomfortable, weird, often funny things that happen when those lines are blurred or crossed,” Lucas tells me.

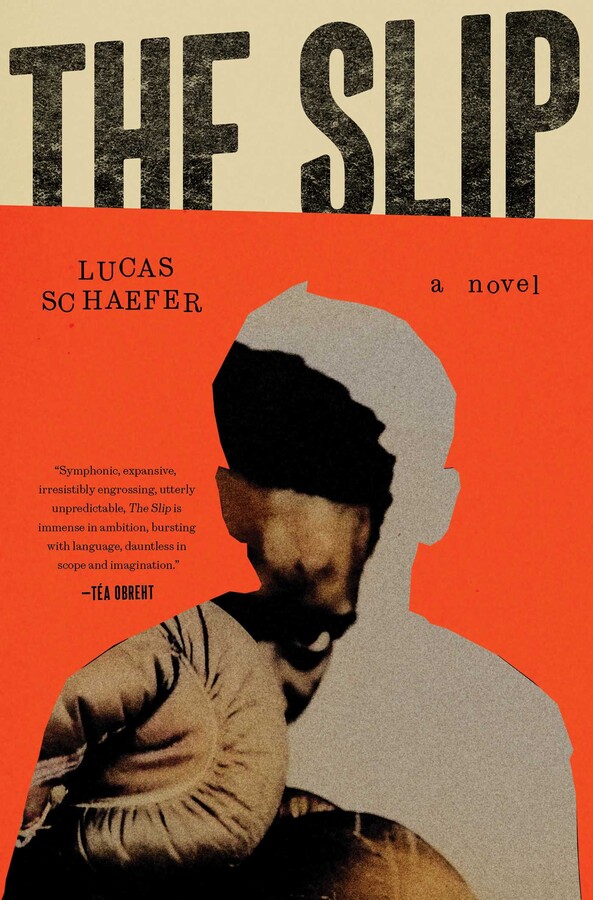

Uncomfortable, weird, and funny—that’s a good place to start with Lucas’s astonishing novel, The Slip (Simon & Schuster, 2025). In a starred review, Kirkus compares Lucas, a forty-two-year-old debut novelist, to Jonathan Franzen, Philip Roth, and John Irving. Pertinent for our purposes here, the review also provides a sturdy one-sentence elevator pitch: “A missing teenager is at the center of a densely populated plot that bobs, weaves, and levitates around a boxing gym in Austin, Texas, from 1998 to 2014.”

That may sound heady, but The Slip is Zadie Smith meets American Pie, as Lucas recently told a group of booksellers in San Antonio. At its heart, it’s a buddy comedy, or tragicomedy.

Here’s the gist: White, Jewish Nathaniel Rothstein gets into a fight at school in Newton, Massachusetts, and is sent for the summer to live with his uncle Bob, a pot-smoking history professor at UT Austin. Not knowing quite what to do with a disgruntled sixteen-year-old, Uncle Bob enlists the help of his boxing gym friend David Dalice, the hospitality director of a local nursing home. Always looking for teen stooges, David happily offers the kid an internship.

David is a larger-than-life Haitian immigrant and retired so-called tomato can—a boxer who is hired to lose matches. At work, David intentionally dons a Kool-Aid Man–like persona full of sexual bravado to manipulate and impress his young charge and survive the racist, demented volleys of the old people he is tasked with entertaining.

From this inauspicious summer internship, a friendship is born when David takes Nathaniel to the boxing gym and begins to train him. At first, Nathaniel prospers: he loses weight, becomes livelier, takes on a healthy glow. Then he disappears.

The twisting five hundred pages of The Slip do so much more than tell the story of what happened to Nathaniel. It’s not one bildungsroman but a dozen of them. There’s a phone-sex operator and her gender-questioning child; a Mexican lightweight determined to cross the border to get back to his high school crush; a shy female cop trying to crack Nathaniel’s cold case. There’s even a dastardly clown who talks in Texas tongue twisters and his intellectually disabled twin brother. Shakespeare, but make it Texas, baby.

I sat down with Lucas to talk about his epic Austin novel in a conversation that bobs, weaves, and levitates, and one that has mercifully been edited for clarity and concision.

Greg Marshall: The Slip opens at Terry Tucker’s Boxing Gym, a fictional hole-in-the-wall gym in Austin, Texas. Tell us about moving to Austin in 2006 and getting into boxing. When did you know you wanted to write a novel about a boxing gym?

Lucas Schaefer: I was a gay guy from the Northeast with artistic aspirations, so after college I moved to Brooklyn, because it seemed like what I was supposed to do. I’ve always had a slight contrarian streak, and it didn’t take long for me to chafe against the imaginary boundaries I’d constructed for myself. There was a whole country out there, and I wanted to experience it. So, I moved to Austin when I was twenty-four, with no real purpose. A very Austin move.

I’d never had an interest in boxing before, but I was already in Texas, trying new things, so when I learned about an evening class at R. Lord’s Boxing Gym on North Lamar, I signed up. Everyone was at the boxing gym. Male fighters, women fighters. Every body type, personality type, race, religion. There were lots of people like me—hobbyists who came for the workout—but also plenty of amateur and professional boxers. Just a sweaty mass of humanity, and everyone working out side by side. I loved it from the second I walked in.

As a writer, I’m interested in those places where people who don’t normally spend time together suddenly do. The boxing gym—a boxing gym—felt like a natural fit for a novel.

GM: In some ways, the character most like you in The Slip is Nathaniel Rothstein. He’s Jewish; he’s from your Massachusetts hometown; he loves musicals. He’s also a character who makes bold and troubling decisions. Can you talk about bringing Nathaniel Rothstein to life and imbuing him with so much of yourself?

LS: As both a reader and a writer, I’ve never been interested in lightly fictionalized autobiography. I like my fiction with a capital F. Give me a big, omniscient narrator. Take me places! I was never going to write a slim volume about a gay man in Austin named Schmucus Schmaefer.

That said, for a long time Nathaniel was not coming to life on the page. He was always White and Jewish, so on the surface we had more in common than I do with many of the characters in The Slip; but I couldn’t get a handle on him. Our writing professor Elizabeth McCracken used to warn us that a character’s bad habits had the potential to become a story’s bad habits, and there was some of that with Nathaniel. How do you write about this blah teenager, this unformed teenager, without writing blah and unformed prose?

I think the aha moment was when I realized Nathaniel was from Newton—the suburb of Boston I’m from—which was not how I’d first conceived of him. Because Nathaniel, at sixteen, is still so undefined, it was important that everything around him be in super sharp focus. That allowed for crisper prose, and it also called attention to his blah-ness in a way that felt illuminating.

It also helped me make that blah-ness feel more fleshed out, more particular to this kid. That’s why I used my real high school—Newton South High School—as Nathaniel’s high school. Twenty-five years later and I can still smell the hallways, unfortunately. I know that place in my bones, and I could conjure it easily. It was almost a Dorothy Gale situation—I put this black-and-white character into a technicolor world, and suddenly I started to see him in color, too.

The other thing that really let me get a handle on Nathaniel was embracing his secret love of musicals. I resisted this at first because it seemed unlikely to me that this sour straight boy would love Man of La Mancha. I mean, I loved Man of La Mancha, but of course I loved Man of La Mancha. I was a precocious gay; my greatest childhood trauma was not being cast in a Super Sour Gushers commercial after making the callbacks.

This was a case, though, of me being reductive, of placing a limit on my imagination based on my own lazy preconceptions. Especially when writing about identity, being reductive is a great way to wreck the whole thing. In a book where so many crazy things happen, I was concerned that having a grumpy hetero teenager love musicals would seem implausible? C’mon.

GM: We’re both elder millennials who grew up at a time when many White kids saw Blackness as aspirational without understanding much about the lived experience of Black people. It was the age of Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, Venus and Serena Williams, not to mention performers like Tupac, Notorious B.I.G. and Dave Chappelle, a favorite among the straight boys of my high school. (You couldn’t walk the halls of Skyline High in Salt Lake City—predominantly Mormon, White, and very suburban—without hearing one guy yelling to another, “I’m Rick James, bitch!”) How does Nathaniel see Blackness?

LS: I think it’s not uncommon for White kids to both aspire to Blackness and be racist, and I knew I needed to explore this contradiction for the book to work. Nathaniel behaves in ways that most readers will agree are problematic. Actually, problematic doesn’t do him justice. Cringeworthy doesn’t do him justice. But he also loves David, his Haitian-born boss, and he has a real friendship with David, and David has real affection for him. I wanted to lean into that complication, to explore why Nathaniel was the way he was, and to think about where it might lead.

GM: The Slip isn’t just about David and Nathaniel. You write from the perspective of a breathtaking number of characters of different ages, races, sexes and gender identities. You’re a White cis gay man. Why do you think it’s important for fiction writers to imagine outside of their lived experience? Why should, say, a Black, Haitian, Mexican, elderly, disabled, or trans reader take a chance on you and pick up a copy of The Slip?

LS: I don’t think any writer is owed the benefit of the doubt. We’re judged by what’s on the page, and we should be. What I can tell you is that I wrote this book with a lot of intention. There’s not a moment in it, not a word in it, that I didn’t consider deeply.

A lot of the discourse around “writing outside of one’s lived experience” seems to come back to this question of who has the “right” to tell a particular story. One of my former writing professors, Alexander Chee, talks about this in a very good Vulture piece, and part of what he says is that the real question a writer needs to ask—and I’m paraphrasing here—is why are you exercising that “right”?

In the case of The Slip, the central questions of the book are all wrapped up in the tensions and opportunities that arise when people of different backgrounds and experiences are forced to interact. There’s no way to write that book, no matter who is writing it, without writing far outside the author’s own experience.

Now, that needs to be done with a lot of care. I let two principles guide me. The first was that each character had to be singular. Nathaniel isn’t meant to represent all Jewish teenagers; David isn’t meant to represent every immigrant from Haiti. To make any of these characters work, I had to understand what gives them joy and brings them pain, what makes them tick. My characters aren’t spokespeople for anyone but themselves.

The second principle, though, was that these are characters who live in our actual world, and all those demographic distinctions that affect how each of us is perceived by others—and sometimes how we perceive ourselves—had to be considered. Politics and time period had to be considered. I wasn’t creating these characters in a vacuum.

Just to give an example using part of my own identity: If I create two gay White male characters, they’re going to sound different from each other and look different from each other and act different from each other because they are two different people. But if these characters are living in the US in 1998, neither can get married or serve openly in the military. That’s just reality. One may react differently to that fact than the other, but the fact remains.

GM: You worked on The Slip for more than ten years, from the start of graduate school in 2013 to doing final copyedits in early 2025. To say you wrote through some of the most troubling events of our lifetime would be an understatement. What’s striking to me is how little your vision for the book changed in all those years. What was the core vision for the book early on? And how did you not lose your way as so much of our world turned upside down?

LS: Not to get too Meryl-in-The-Devil-Wears-Prada, but I don’t think the role of the writer is to figure out where the culture is and then write something aimed at appealing to that. The role of the writer is to put our imprint on the culture. To shape the culture. I’ve always felt that. And from the beginning, I’ve had a strong vision of the questions I wanted to explore in The Slip, of the themes that matter to me. What I didn’t have was the skill to make it happen.

You hear a lot of grumbling about MFAs, but the truth is that an MFA is amazing for teaching you how to read and for teaching you how to write. What an MFA can’t give you—what no one can give you—is something to say. And with this project, from the beginning, I knew I had something to say. So, the question wasn’t one of vision, it was of figuring out how to structure the story, of how to balance all these characters, of how to write a novel.

As for not losing my way, I think a lot of it (and you can confirm this) is that I’m stubborn. I knew these questions were worth exploring, and I was set on exploring them.

But also: all the terrible things that happened after I started writing the book only made me more committed to writing the book, because none of those things happened in a bubble. They all came about because of problems we already had. So, I just kept on keeping on. It’s not as if being preoccupied with the extremely weird things that can happen when racism rots our brains became less relevant after the 2016 election.

GM: In spite of all the imagination and truly wild things that happen in The Slip, the novel never lapses into satire. Can you talk about your relationship to satire, especially when many recent excellent novels about race can fairly be describe as satire?

LS: As a reader, I love satire. But as a writer, and especially as a White writer, I wanted to stay as grounded in realism—or something resembling realism—as I could. For me, it felt like going in a super satirical direction was a way to ensure that no matter what I wrote or how people perceived it, I could always fall back on Well, this is supposed to be funny. And I wanted to remove that guardrail.

One flaw in my early writing, I think, is that I could be a little flip, or display a bit of aloofness, some distance between me, the writer, and my characters. And that’s not the book I wanted to write. I wanted to feel what my characters were feeling and to be embarrassed when they did something embarrassing. I wanted to go for it emotionally. And I don’t think I could’ve accomplished that working in a more satirical vein.

I wanted to write a book where all these wild things happen but we never lose sight of the process. This may sound unbelievable, but I’m going to make you believe it. That was the goal.

GM: It’s been fascinating to hear early reviews describe The Slip, accurately, as a crime or mystery novel—fascinating both because of the generosity of these reviewers to invite your very character-driven work into their adored genre and because the crime and mystery components of the book were part of a massive overhaul you pulled off after the book was under contract. Walk us through that revision process.

LS: For a long time, I thought I was writing a book of linked stories. I love A Visit from the Goon Squad, and I wanted to do for boxing what Jennifer Egan did for music. This didn’t work for two reasons. One is that unlike Jennifer Egan, I’m not equally adept at going short and going long. I want to make a big mess, always. I was trying to cram these grand narratives into my short fiction, and it occasionally worked, but mostly it didn’t. Oh, a short story is supposed to be short? Who knew?

But the second problem is that the book, in those early years, never had the right throughline. The themes were there, the big ideas, but not the plot. If you’re in a relationship, there’s that one thing your partner always says that just annoys the shit out of you, and from about 2013 to 2016 it was you telling me that there should be a heroin ring at Terry Tucker’s Boxing Gym. I don’t know why you fixated on this idea. What even is a heroin ring? Were they dealing heroin? Were they on heroin?

Anyway, that was not the direction I wanted to go, but you were right it needed something, and that’s how Nathaniel’s disappearance came to be the central event of the novel. A weird thing about this process is that I’d done a bunch of the legwork to write a mystery from the beginning. For example, I knew early on that I wanted one of the gymgoers to be a police officer. So, a friend and I enrolled in Austin’s Citizen Police Academy, which is this weekly course for community members at police headquarters, and I went on a couple of overnight ride-alongs with patrol officers. But it wasn’t until deep into revision—years later—that I figured out how those experiences would inform the book.

Once I understood the centrality of Nathaniel’s vanishing, I also started reading a lot of crime fiction. I learned a lot from writers like Attica Locke, Richard Price, Eli Cranor, S. A. Cosby, and Patricia Highsmith, especially about plot. Those great crime writers know how to craft a plot.

GM: In addition to a mystery, The Slip has also been billed as a Great Texas Novel. Do you agree?

LS: For many years, when I’d go back to the Northeast and the subject of Texas came up, people would offer some version of “Oh, but you live in Austin, not Texas.” And I’d agree. But I’ve come to resent that line of thinking and push back against it. It’s a given on the reactionary right that Texas’s major cities—which generally vote Democratic, by the way—don’t represent the “real” Texas. A lot of less overtly ideological commentators have adopted some version of this line of thinking, too. But almost a million people live in Austin. Houston is the fourth largest city in the country. Dallas and San Antonio are in the top ten. Why do these millions of people—who are central to creating our culture and driving our economy—not count?

This same corrosive nonsense has been playing out on the national level my entire life, to deleterious effect. You’re only a “real” American if you believe x, y, or z, and x, y, or z is always the dumbest idea imaginable. And, of course, there’s always a racialized element to who is “real” and who is not.

If you can tell this topic animates me, it animates much of The Slip, too. One thing that unites all these disparate characters is their sense (usually correct) that the broader society doesn’t take them seriously, that they’re destined to be supporting players in someone else’s story. The tension in the book comes from those moments when they push back, when they say, Sorry, assholes, I’m the protagonist now.

So is The Slip a Great Texas Novel? I hope it’s great, but that’s for others to decide. What I can say for sure is that it’s Texas.

Greg Marshall’s memoir Leg (Abrams, 2023) was named a best book of the year by the Washington Post and the Texas Observer and was a finalist for the Randy Shilts Award and a Lambda Literary Award. His essay “Corey” originally appeared in SwR and won the McGinnis-Ritchie Award for Nonfiction in 2021. Marshall is a graduate of the Michener Center for Writers and the recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. He lives in Austin with his son, his dog, and his husband, the novelist Lucas Schaefer.

More Interviews