Breaking the Quiet | An Interview with Elijah Burrell

Interviews

By Sadie Shorr-Parks

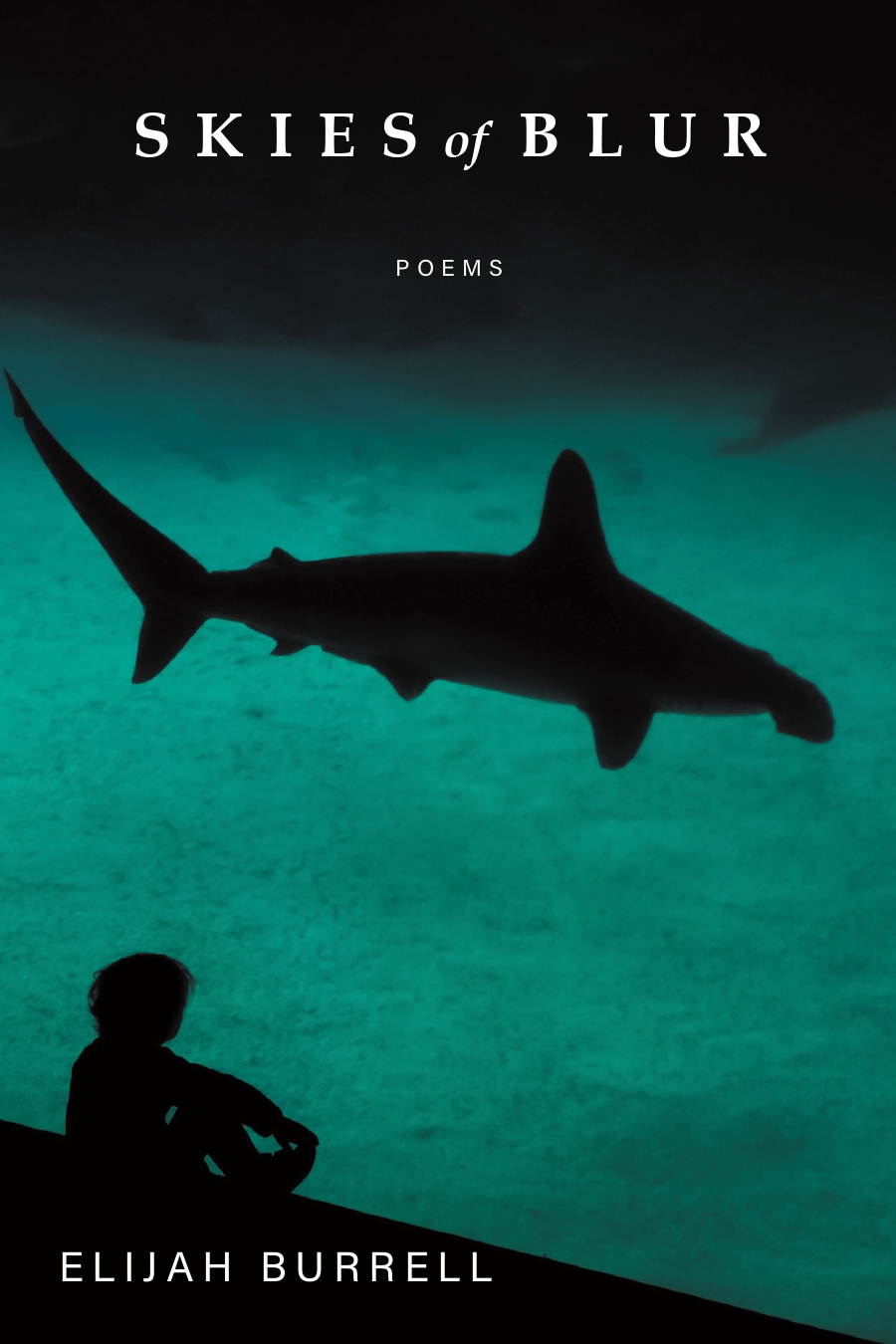

You would have to forgive a twenty-first-century grieving person for feeling alone in their grief. In the nineteenth century we had black mourning clothes, mourning wreathes for doors, and other robust traditions to help a grieving person understand and mark their new position in the world. Despite the mass death in our country brought on by COVID-19, gun violence, and disease, we are still struggling to establish language to communicate our mourning to others. In Elijah Burrell’s new poetry collection Skies of Blur (EastOver Press), he alchemizes the incomprehensible nature of death and grief into language, gifting readers with an intimate, profound, and at times wry understanding of the inner world of grief, and in doing so, offers the grieving person the words needed to reconnect to the world.

In Skies of Blur, the follow-up to his well-received 2018 collection Troubler (Aldrich Press), Burrell sets his vivid eye on the post-2016 American landscape, pulling the blur of the last eight years into poetic clarity for the reader. By layering poems about gun violence, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the death of Burrell’s own mother, Skies of Blur constitutes a profound contribution to our understanding of American grief and isolation.

This interview took place over email.

Sadie Shorr-Parks: I was struck by the way sound—specifically music—and silence operate in Skies of Blur. I’m thinking of “The Asteroid Fell Out of the Sky” and “Even the Best Records Have Gaps Between Tracks.” Elvis Presley and Elliott Smith both make appearances in the book. I was wondering if you could speak a bit about the role music plays in the collection.

Elijah Burrell: It’s like what John Cage said about 4’33”, his silence piece, that there’s no such thing as silence. There’s always something in the air: maybe wind, or, later, raindrops tapping a roof, or the sounds of human experience breaking the quiet—the deep breaths, the sighs, the buzzes from text conversations. Often, the emotional impact of the absence of those things becomes as meaningful. When we lose something and the familiar voices and sounds vanish, there seems to be a silence, a pause, but there is always something else to fill in the spaces. I think that’s what a lot of these poems are built on. It might sound strange, but I think of music as a companion—a friend. I write in musical shorthand and rely on listening to music when I write and when I don’t. As you pointed out, I mention Smith and Presley in the collection, but there’s also mention (direct and indirect) of Tom Petty, Sonny Boy Williamson, Bob Dylan, and Jeff Lynne among others. I guess those artists just made sense in the moment.

SSP: Alongside music, grief also permeates the collection. The book begins with the speaker singing a song about the death of their mother and ends with the image of your daughter playing guitar, moving her fingers “down the neck like a surgeon closing a wound / that’s lain open too long.” How did writing these poems impact your own grieving and your understanding of grief?

EB: I reckoned most with my mother’s death in the final half of my book Troubler. Skies of Blur starts with some remnants of that unresolved, deep-rooted hurt. The poems you mention act as prelude and postlude—words that carry spiritual meaning. I tried to communicate the headspace I was in (in this case, I’m the speaker in these two poems) via the title of that first poem, “Prelude / Headspace.” A prelude is the first act of ceremonial, spiritual worship.

When my daughter plays her guitar, to me it is a crystal-clear, unequivocal act of love. In the case of this final poem, “Postlude / Grace” (a title that comes from the closing of worship, my daughter’s literal name, and a word for kindness and salvation), that healing love is the final word in the book—the final act of worship—that throws the speaker a lifeline and provides the possibility of rescue.

SSP: One aspect of Skies of Blur I enjoyed was how many tethers were cast to the outside world, whether by using found poetry or by citing specific news articles in epigraphs. I was especially intrigued by how often gun violence came up in the collection. What drew you to specific news events, and how did you go about turning them into a poem?

EB: My eyes always scan headlines for the nonsensical and astonishing. I was writing several of these poems in the aftermath of the 2016 election, so there was no deficit of absurdity in the air. One day, I found myself reading about these folks who stole a horn shark named “Miss Helen” from the San Antonio Aquarium by lifting it from a tank and placing it in a baby stroller. Can you imagine coming up with a plan like that? The anticipation of driving to the aquarium and rolling that stroller through the doors? Think of the adrenaline. Then I thought about Miss Helen—how she was chosen above all other fish and lifted from her transparent cage, the literal barriers and complications of her horn-shark life. This story made me giddy.

I am an American. The threat and thought of gun violence is inescapable. My children are accomplished at active shooter drills. I teach in university classrooms where my students all hold their breath when someone walks into the room ten minutes after class has started. Recently, when I was at an Apple Store, a man fell off his stool, making a horrendous bang against the stone floor. The hundred or so shoppers went silent for a beat before they knew they’d not been shot. In this book, as they do on the nightly news, mass shootings take up most of the oxygen. But then there’s the girl in our town whose boyfriend shot and killed her while cleaning his gun. There’s my student Vaughn King Jr., who went home on break and was shot to death in a park by two strangers. I remember in the very first days of October 2017—a day or so after the mind-blowing story from the Las Vegas Strip about the guy who opened fire from his hotel window and shot hundreds of people at the music festival—when news broke that Tom Petty had been found dead in Los Angeles. I made my youngest daughter a bowl of Cheerios that morning and hadn’t spoken to her about either story. It broke my heart when—from nowhere—she began to hum Petty’s song “Yer So Bad” as she ate her breakfast. That’s where the poem “In a World Gone Mad” comes from (the title is a nod to a repeated phrase in that song). I suppose all this and so much more is where poems like “American Umbrella” came from as well.

SSP: There are so many striking and emotional nature images in this book, many involving water and forests. Was there a specific place or landscape you were referencing in the book? What about the setting inspired you?

EB: I’m charmed by writers who can make me believe in their setting. I’m thinking of poets like Heaney, Trakl, Tranströmer, and Stanford. These writers present a sense of place that’s utterly familiar to residents of, say, County Derry in Northern Ireland (and the squelch of soggy peat), the Delta regions of Mississippi and Arkansas, monochrome Stockholm, yet write it in a way that can still feel marvelously, emotionally alien. I was born and raised in mid Missouri near the Missouri River. For most of my young life, I lived on rural gravel roads—a land of hills and hollows. You walk out into the woods, and you’re bound to emerge in some field that connects to other fields that stretch out as far as you can see. When I stumbled upon the story about naming old Irish fields and the concept of stray fields, the mystery and magic felt personal. I rode unfarmed fields on horseback as a kid and lost my way. Sometimes, I’d do it on foot. I’d walk out into nowhere and swing my leg over barbed wire to climb from one acreage to the next. These memories fill the mind, so the mind becomes its own collection of fields. During some periods of life, the mind becomes a place to scuffle with reality.

SSP: When reading Skies of Blur, I noticed a reference to COVID-19 in “Memories from This Week Two Years Ago” and epigraphs quoting news articles from February 2020 and May 2020. I was curious if you wrote this book during the COVID pandemic and if the pandemic informed the collection at all.

EB: You noticed the threads of distance, isolation, loneliness, and separation sewn throughout these poems. Yes, I worked on this book during the pandemic. We went through it like everybody else in all the obvious and standard ways. My wife is a physician, so each day became more difficult for her and more worrisome for our little family. I learned to adapt to life in the university classroom (and remotely), and my kids did their best to stay interested and engaged through a computer screen. We lost several loved ones to COVID. We also lost several friends who, for varied reasons I’m sure, decided that to stay prudent and informed was equal to both personal and political hostility. A subcurrent of isolation and separation runs directly through this book, and I’m sure I placed it into the poems as a reaction to that deep, formidable dread most of us felt at the time. After all, the best defense was distance. Its bizarreness breaks my heart still. You can see this most obviously in poems such as “No One Likes to Be Let Go” and “Hailing Old Ghosts from My Silo on the Moon,” but the pandemic probably seeps into every poem in this book.

Sadie Shorr-Parks is author of Honey Month (Main Street Rag). Her writing has previously appeared or is forthcoming in Appalachian Heritage, The Florida Review, Blueline, Cimmaron Review, The Hongkong Review, Lines+Stars, Painted Bride Quarterly, Sierra Nevada Review, Southwest Review, among others.

More Interviews