Brenda Navarro | Two Voices in the Dark

Reviews

By Julián Herbert (Translated by Robin Myers)

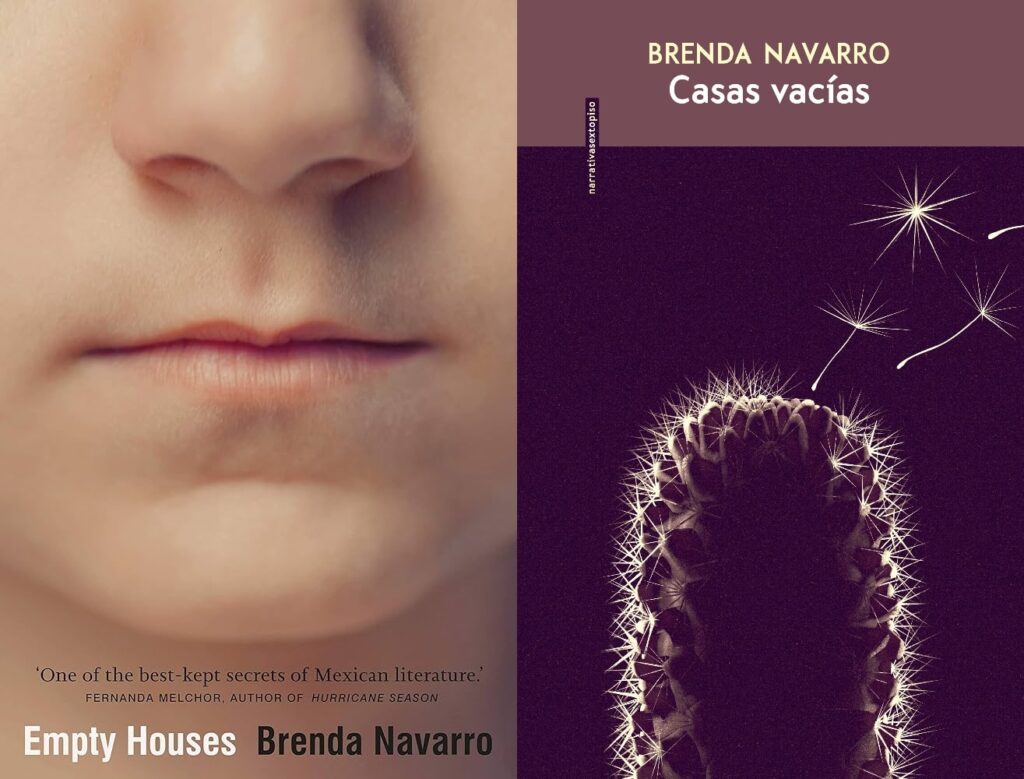

TThe first time I read Casas vacías (Sexto Piso, 2019), by Brenda Navarro, translated by Sophie Hughes as Empty Houses (Daunt Books, 2021),[1] I thought obsessively about a story by Inés Arredondo: “En la sombra” (“In the Shadow”), included in the collection Río subterráneo (Joaquín Moritz, 1979). The obvious link between the two works is the presence of a park. In the novel, one of the two first-person narrators (both nameless) informs us that she’s lost her three-year-old son Daniel in a public park while texting angrily with her lover Vladimir. In Arredondo’s story, the first-person narrator (also nameless) finds herself in two different settings within just a few pages. The first is her house, where she spends a sleepless night waiting for her husband, who’s with another woman. The second is the park, where the main character stops the next day on her way back from the pharmacy (to buy her daughter’s medication, it seems) and is lasciviously spied on by three homeless men.

Both in Navarro’s book and in Arredondo’s story, I see the park as a dialectical image where dualities converge. I don’t intend to grant this idea any kind of objective validity, but rather to describe the mental content that Empty Houses stirs in my memory. I’ll explore the apex of this content, then try to connect it to the stylistic range of Navarro’s novel.

The first duality I notice is the perspective and the spatial-temporal framework. “En la sombra” is narrated by a single voice, but it’s set in two spaces (the home and the park), separated by an ellipsis. For its part, Empty Houses transpires in two mental experiences: the voice of the woman who lost her son (Daniel) and the voice of the woman who kidnaps him (and calls him Leonel). In both narrative worlds, the park functions as a hinge between the intimate and public realms. Another duality I’ve identified is that of social strata: the drifters observing Arredondo’s narrator make their class resentment plain, and the kidnapping of Daniel/Leonel is charged with a similar ideological feeling. What’s more, the catalyst for both stories is the erotic tension produced by a discordant third party: the husband’s anonymous lover in Arredondo’s story, and the lover Vladimir in Empty Houses. Shame and guilt are two other forms of emotional energy that converge in the dialectical image of the park. The narrator of “En la sombra” is ashamed to have been betrayed by her husband, and she feels guilty to be desired by the drifters, the third of whom exposes himself. Navarro’s first narrator returns to the park again and again, trying to identify exactly where she made her crucial mistake so she can flagellate herself; at home, she berates her husband Fran, demanding that he blame her for her distraction (an erotic distraction, unbeknownst to Fran) during the kidnapping. The second narrator of Empty Houses resents the fact that she’s been left by her lover Rafael, who refuses to ejaculate inside her (an image that also appears with calculated obscenity in Arredondo’s story). This is what leads her to kidnap Leonel: a decision that will later cause her ambiguous suffering (shame, rage, guilt) when she learns the child is autistic.

As I wrote the previous paragraph, I returned to “En la sombra” in search of a key I thought I’d overlooked in presenting this sequence of dualities, this dialectic reading. What I found, and what made sense to me, was the following passage:

There was a peculiar contrast between the deep, calm blue of the sky and this small patch bathed in lunar light that slanted down onto the park, granting it two faces: one normal and the other false, a kind of dazzling shadow. I sat on a bench and watched how the branches, shifting in the gusts of wind, showed one side of their leaves, then the other, alternating this way in the unsettling light that made them look like brilliant ghostly jewels. It was as if we were all outside of time, under the influence of a spell that no one seemed to even notice. The children and their nannies were still there, as they always were, but they moved about without making any noise, without shouting, and as if suspended in an attitude or action that would carry on forever.

I don’t know if Navarro has read or remembers Arredondo’s story, but I struggle to separate this paragraph from Empty Houses—in part, perhaps, because of Navarro’s remarkable aesthetic achievement in locating her two protagonists/narrators within a kind of loop outside of time: the moment when they pass each other in the park, inside a space of ominous imagination that resembles what Arredondo has described.

![]()

Some years ago, I interviewed Chuck Palahniuk and asked about his use of the first person in Fight Club. His reply: “I was studying minimalist technique back then. Minimalists find the first-person point of view more authoritative.” Later in the same conversation, he added, “In most of my work, I present fiction using a device of nonfiction. By making use of a nonfictional context . . . I can grant realism and gravitas to stories that would otherwise seem too ridiculous . . . There has to be a balance between the free, creative side of storytelling and the formalization of that same act.”

Turning back to Empty Houses, I’d like to train Palahniuk’s observation on the triangle formed by minimalist prose, first-person narrative authority, and the notion of the formal device.

While Navarro doesn’t use a concrete device to transmit her first narrative voice, this voice does convey a certain emotional state (extreme agitation, depression) that formalizes the tone:

With Daniel gone, I gained a new-found respect for people who are able to talk about their feelings. Who can share, empathize. I felt as if I had something trapped between my lungs, windpipe and vocal cords. It physically hurt, the effort to talk, like a hand choking me.

Through this emotional disturbance, which captures the story’s peculiar muteness (its overt reluctance to operate as oral testimony), the narrator not only economizes events in a believable way, but also forges the authority she needs to travel through patches of time and space: she leaps wildly between anecdotes; compacts the other characters (who seem to unfold around the protagonist as if circling a ghost) into brief, efficient sketches; and, most of all, injects the story with a hyper-concentrated pathos that links the tension and ambiguity of the narrator’s pregnancy and motherhood with the femicide of the mother of Nagore, the girl she finds herself adopting—without forcing the pieces together or making them feel out of place. The emotional device grants harmony to the multiplicity and disjointedness of her discourse; so does the curt, punctuated rhythm of her prose, as we often find in minimalist technique.

Daniel disappeared three months, two days and eight hours after his birthday. He was three. He was my son. The last time I saw him he was between the see-saw and the slide in the park where I took him each afternoon. I don’t remember anything else. Or maybe I do: I was upset because Vladimir had texted to say he was leaving me because he didn’t want to cheapen everything. Cheapen it, like when you sell something valuable for two pesos. That was me the afternoon I lost my son: the woman who, every few weeks, said goodbye to an elusive lover who would offer her sex like some kind of bargain giveaway to make up for his leaving. That was me, the conned shopper. The con of a mother. The one who didn’t see.

I’m going to take a further risk by introducing the concept of dialectical realism as coined by José Revueltas: the aesthetic notion that behind the force of selection and organization that the implicit author applies to reality, there is a “fundamental direction,” an “internal movement,” a kind of symbolic framework or tenacious side where “reality obeys a progression that is subject to laws.” (The cited phrases are from “A propósito de Los muros de agua” [“On Walls of Water”], the prologue Revueltas added to his novel in 1961.) This approach allows me to emphasize the anticlimactic nature of a decidedly un-proactive narrator, who seems to resign herself—though not without anger—to the things that befall her just beyond the bounds of her will and control. This character’s energy comes primarily from outside (an outside embodied both geographically and symbolically by her trip to Spain, where she witnesses a femicide in a liminal way): from her pregnancy, which stirs internal doubts but not resistance per se; from the arrival in her life of Nagore; from a functional (at first) but unsatisfying marriage; from an affair both intense and superficial; from an overwhelming experience of motherhood that ultimately transforms into frustrated longing once little Daniel disappears. The narrator doesn’t foster these situations, nor does she avoid them; she re-signs herself in response, in a translucent metaphor for the spirit of the middle class. The twist, which moves the narrator and Navarro’s readers alike, is the tragic sense of having lost what you once belonged to, even if you’ve failed to want it enough.

The key contrast between this first narrator and the second voice that appears and complements Empty Houses is emotional in nature. The second narrator (the working-class woman who kidnaps Daniel) constantly tries to control her own reality through existential swerves such as dropping out of school, starting a business, moving out of the house she shares with her mother, striving to make a home with her lover Rafael, and trying to get pregnant. Navarro constructs the two characters’ disparate consciousnesses not simply by recounting what happens to them, but through her prose style, which is more casual and dynamic in the second case:

My mum and I had a problem, which was that we didn’t think alike in any way. I don’t know where I learnt to make sweets and cakes, but I’d always been good at it and I knew it could earn me a living. Maybe it’s true that you have to have been born under a lucky star to make any money, but what mattered more when trying to impress the ladies in their cake shops was to make the product taste good, not just nicely decorated but delicious. I don’t know if I was born under a lucky star, but I did have a gift when it came to baking, and I’d take those women samples of my cakes and lollies and say, go ahead, try one on me, no strings attached, but I think you’ll see you won’t be able to resist a second. And then I’d humour them, so how’s your daughter? She’s very pretty, I’ve seen her around, and how’s that pain you had, is it any better now? Go on, look, I brought you some more flavours, get them while they’re warm because they’re fresh out of the oven and I brought them just for you. And the señoras would laugh and say how kind I was, and then I’d sell them my lollies, chocolates, baked apples, cheesecakes, cakes and decorated jellies. And once I could see that it really did pay enough to live on, well, I quit school, which was the last straw for my mother. At first, to try and keep her happy, I gave her a share of my earnings, but my mum is the sort of person who when she’s angry about something is really, really angry. So just for the hell of it, she’d turn off the gas, crazy things like that, and I’d go and cook at my aunt or cousins’ houses instead. Afterwards I’d go home with the money I’d made and tell my mum there’s your gas money, you know how fast it runs out! She’d pocket the cash but I couldn’t change her mind. She never liked me dropping out of school.

I translated this long paragraph in its entirety because I’m interested not just in what it tells us about the character, but also in its condition as a latent device: a stylistic feature that warrants digression.

From the standpoint of the twentieth century, the narrative conventions of realism as applied to lower-class or minimally educated characters (both situations confessed by the first-person voice in the example above) oscillate between two poles when it comes to point of view: either an omniscient third-person perspective that allows the implicit author to poeticize, speechify, and sermonize (one of Revueltas’s favorite techniques, also employed by Carlos Fuentes and Ricardo Garibay), or a first-person perspective that mimics oral discourse (as we find in Juan Rulfo, Edmundo Valadés, Garibay again, Josefina Estrada, Armando Ramírez, et al.). What I perceive in Navarro’s second narrator, both in her punctuation and in her syntactic turns, is a discourse formalized by a different device: testimonial literature. I don’t mean the emulation of audio transcriptions or the sieve of legal depositions, but the mimesis of a written working-class language whose contemporary centers of production are generally workshops in communities, prisons, self-help programs, etc., largely attended (I make this claim as a workshop instructor myself) by women. Such sources participate in what Josefina Ludmer calls “post-autonomous literature,” and no small number of contemporary Mexican writers have drawn from it: Cristina Rivera Garza and Emiliano Monge, for example. In implementing (as Palahniuk suggests) this nonfiction device in a work of fiction with a less-than-obvious social vocation, Navarro grants it a fresh and distinctive turn.

Things happen quickly for the first narrator in Empty Houses, within a compact timeline marked by the sudden aura of the turning point (femicide, kidnapping, biological motherhood compounded with unexpected adoptive motherhood). For the second narrator, however, misfortune is a gradual process constructed for years, decades, even generations: her mother’s rape by a relative, her brother’s unpunished death in an accident at work, proverbial economic hardship, the slow course of her seduction and abandonment by Rafael, fruitless attempts to conceive and move abroad. Here, revisiting Revueltas’s concept of dialectical realism, I find a symbolic interpretation of social fate in the arc of both characters: crisis as a marker of middle-class identity; the futile pursuit of social mobility as the destiny of the working classes.

It’s clear to me that the central theme of Brenda Navarro’s debut novel isn’t social injustice, but motherhood—with all its anguish, frustrations, and semi-secret iniquities. What I find compelling about the lateral and symbolic focus I’ve proposed here, though, is the implementation of a tragic literary complexity—tragic in the sense ascribed by Walter Muschg to this word in Historia trágica de la literatura (FCE, 1965): “tragic in the sense of critical” (9). This interpretation, plus the lattice of dualities described early in this essay, returns me to the dialectical image of the park: a hinge that (unites and) sunders the public from the intimate; the social from the existential; the rhetorical mechanisms of fiction from the postmodern ideation of testimony.

[1] Translator’s note: All passages cited from Empty Houses are from Hughes’s translation. All translations from “En la sombra” and other cited texts are my own.—RM

Julián Herbert was born in Acapulco in 1971. He is a writer, musician, and teacher, and is the author of The House of the Pain of Others, Tomb Song, and Bring Me the Head of Quentin Tarantino, as well as several volumes of poetry. He lives in Saltillo, Mexico.

Robin Myers is a poet, translator, essayist, and 2023 NEA Translation Fellow. Her latest translations include Last Date in El Zapotal by Mateo García Elizondo (Charco Press), A Strange Adventure by Eva Forest (Sternberg Press), What Comes Back by Javier Peñalosa M. (Copper Canyon Press), and The Brush by Eliana Hernández-Pachón (Archipelago Books). A collection of her poems, Centro, is forthcoming in 2026 from Coffee House Press.

More Reviews