Copi’s Queens

Reviews

By Federico Perelmuter

To say that Copi, Argentine-French cartoonist, playwright, actor, and writer, was born destined for his stellar career would be rather ironic considering the subject at hand, but true, nevertheless. Thus, an obligatory, prefatory genealogy, justified (only partially, I know) by its explanatory power: Copi was born Raúl Damonte Botana in Buenos Aires in 1939. His maternal grandfather was Natalio Botana, founder of the influential sensationalist newspaper Crítica and a publishing magnate who patronized Jorge Luis Borges and Roberto Arlt and is often compared to William Randolph Hearst. His grandmother, Salvadora Medina Onrubia de Botana, was an aristocratic anarchist poet and novelist who allegedly funded the escape of anarchist and police-chief assassin Simón Radowitzky from Argentina’s Alcatraz equivalent and attended anarchist party meetings in a limousine. His father, Raúl Damonte Taborda, was a Peronist who broke with Juan Domingo Perón and thus had to flee to Uruguay and, eventually, France, where Copi settled permanently in 1962 until his death in 1987.

Because he wrote in French and was translated into a slightly grating Spain Spanish (that Jorge Herralde, Anagrama head honcho and Copi’s Spanish publisher, says he did not mind), Copi was largely forgotten in his native Argentina. That changed when César Aira gave a series of lectures later collected in a book published in 1991 and elegantly titled Copi. Aira inaugurated an effort to claim Copi as Argentine—ironic considering his disdain for nationhood yet inescapably true if you read the work—that combined with queer theory’s rise and its construction of a genealogy of gay Argentine literature, at the center of which Copi and Manuel Puig were eventually placed.

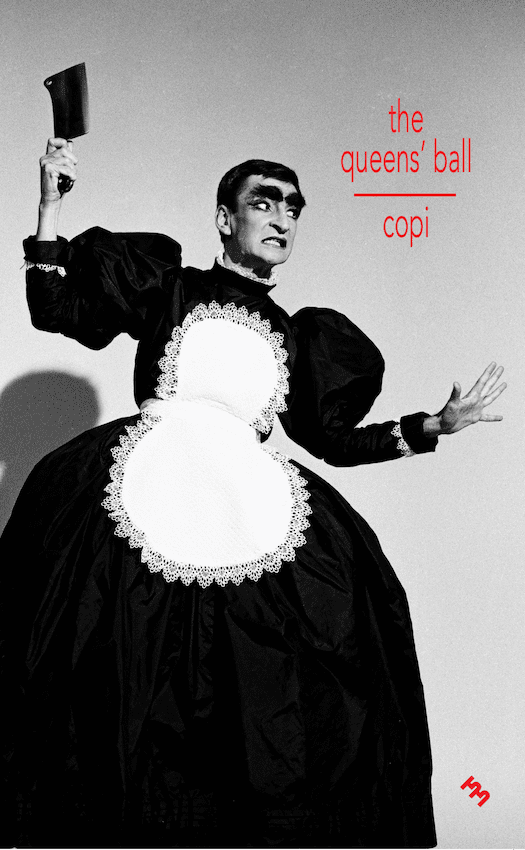

Though he was most known as an actor and playwright during his lifetime, Copi began writing prose in the 1970s and lived to publish a handful of novels and two short story collections. In April 2024, Inpatient Press published what Aira described as Copi’s masterpiece, The Queens’ Ball, first published in French in 1977. Kit Schluter, the translator, has captured Copi’s twisted poetry of speech and unique synthesis of French and Spanish, not to mention his disregard for gender norms and love of travestis, a Hispanic and French trans archetype with no real analogue in Anglophone culture, and locas, folles, which Schluter rightly translates into the English queens. An afterword by Copi’s current French editor, Thibaud Croisy, and a series of notes describing the map of Paris’s queer nightlife in the 1960s and ’70s that The Queens’ Ball draws, make this edition commendable and long awaited.

The Queens’ Ball is Copi’s second novel and, like his others, features a narrator called Copi (“because that’s what my mom has always called me, I don’t know why”). The author/narrator has received an unreasonable advance from his editor for a book he hasn’t yet begun—”the subject of which must not be very interesting to me”—and which he won’t recoup. (This might be the novel’s most far-fetched element for the contemporary reader.) Copi calls the text a “crime novel,” though sans cops: “I don’t like that part of crime novels.” The novel follows, over fifteen years or so, the amorous triangle between Copi, his beautiful Italian lover Pietro/Pierre, and Copi’s wife, Marilyn, a rather unpredictable drug dealer and clairvoyant with whom Copi competes for Pietro’s affections. After years of estrangement, and by sheer coincidence, Marilyn is found to have hanged herself in the hotel room next to Copi’s own.

Guilt, consequences, and their seeming absence are a key thread running through The Queens’ Ball, whose ceaseless churn of languages, events, and characters will dizzy and arouse in equal measure. From Copi losing a leg below the knee after Marilyn’s pet snake latches onto his calf so aggressively that firefighters (why firefighters? I have no clue) must saw its skull in half, to Pietro’s preference for the penetration and fondling of his bellybutton, which was “deep and smelled lightly of ass.” Michael, Pietro’s deaf American lover, likes “one thing and one thing only, which is having his dick bitten,” and brings around “seven-year-old hippie triplets” Piggy, Moonie, and Rooney. Their mother has been jailed in Ibiza on drug charges, and the kids become part of the roaming troupe that includes Marilyn, Pierre, and Copi until, in a freak accident, a shark violently kills all three children while leaving the adults unharmed. In another remarkable scene—inspired, allegedly, by a conversation with Michel Foucault at the Continental-Opéra Baths in Paris—the narrator, hiding from the police after killing Marilyn’s mother, blows up the boiler by simply raising its temperature beyond safe limits, killing and grievously injuring the queens using the facilities. Tragedies and horrors accrue with little explanation or emotional load, as if everything could be rolled into a joint and smoked away—weed and drawing being the narrative’s only constants.

Fame first arrived for Copi by way of graphic humor and cartoons. His Femme assise—a comic strip named in homage to Apollinaire’s novel that ran in Le Nouvel Observateur in the ’60s and was a runaway sensation—was an icon of the soixante-huitards. The simple cartoon features the titular seated woman speaking and emoting with almost imperceptible shifts in her mouth position while meditating on trivial, seemingly reasonable states of affairs, whose absurdity the strip makes apparent in its minimalism. Such simplicity contrasts with the luxuriant intensity of Copi’s novels and plays, and, though almost entirely devoid of politics or real-world reference, the comic took what literary critic Daniel Link describes as Proust’s great queen—the all-surveilling, all-critiquing, bedroom-bound Tante Leonie—into the hypermediated postwar French landscape.

Queens populate Copi’s work, which Link describes as an extended treatise on the queen and not, God forbid, the somber and Protestantly respectable “Germanic . . . homosexual.” Histrionic and excessive, always laughing and cracking wise, Copi’s queens uncover in every pointed remark another identitarian contradiction, another absurdity brushed under mundanity’s rug. Hence Copi’s disregard for pronouns, addressing queens freely as “he” and “she” in the very same sentence of The Queens’ Ball and the rest of his fiction. No identity remains stable or particularly clear: not the major things, like pronouns, or the small things that Femme assise remarks upon. Pronouns are no marker of truth, just a referential shorthand. Copi’s casual ease with instability is the mark of his true genius: nothing, truly nothing, is safe from his destructive wonder, and what follows the demolition is only more astonishing.

Concurrent with his career as a graphic artist, Copi devoted himself to the theater, first alongside the Panic group formed by Fernando Arrabal, Alejandro Jodorowski, and Roland Topor and then, by the late 1960s, in his own plays. The most famous of these was Eva Perón, which premiered in 1970 and raised a shitstorm so large that a bomb was placed in the theater (allegedly by associates of Perón, who was then exiled in Spain), and the run had to be completed with police supervision, while Copi was banned from entering Argentina until 1984. In the play, Evita—Perón’s wife and the Peronist icon for social justice, dead by 1952 of cervical cancer, her corpse stolen in 1955 and missing when the production opened—was played in drag by Facundo Bo. Excising the source of Evita’s tragedy, Copi ironically inverted both Peronist lore—Evita as the movement’s childless “mother”—and anti-Peronist accusation—that she was the real Man behind Perón. Trans Evita lacks the agent of her demise, and thus lives on, and the play takes an unforgiving look at the inner workings of Peronist power and mythos.

In case it’s unclear, Copi was no salt of the earth Peronist, but unlike most Argentine anti-Peronists—who are prone to self-loathing, ignorant reverence for the first world à la Javier Milei—he took omnivorous interest in national mythologies, which he gutted with glee. His work spits upon lazy nationalism: writing almost entirely in French with excursions into Spanish and inserts in English and Italian, Copi mocks those who grant nationhood any transcendent meaning. In his hands, most identity categories turn into putty, props, or butts of a cosmic joke. Characters upend names and genders like they’re changing clothes; appear, disappear, and reappear with little explanation; never quite seem to work or work nonstop; fuck and forget; blitz dreams and reality into a higher tonic.

Belonging, for Copi, was to be found only in such constant processes of transformation and self-transcendence. Whether in cartoons, plays, novels, or stories, in his hands everything from nationality to gender to art to a simple doodle of a seated woman morphed into an ideal decrepitude: stasis was death, or worse, boredom. The need to belong, however sincerely felt, was a mistake, or at best just a tactic to dodge the cops. In The Queens’ Ball, a globetrotting, time-jumping, and oneiric “crime novel,” Copi satirizes and destroys himself: a successful, famous, bourgeois expatriate cartoonist living large in the glamour of gay Paris, New York, Ibiza, and Rome in the 1960s.

And yet, what remains after the travails from the bar to the beach to the bathhouse to the bakeries, to the monastery and the church and the restaurant? Copi concludes with characteristic simplicity. Speaking to Marielle de Lesseps, the aristocratic scion to whom the novel is dedicated, he says: “We give each other a kiss on both cheeks, I grab my suitcase, I go.”

Federico Perelmuter is a writer. He lives in Buenos Aires.

Illustration credit: Literary Estate of Copi.

More Reviews