Desperate Searchers | Andrés Felipe Solano’s Gloria

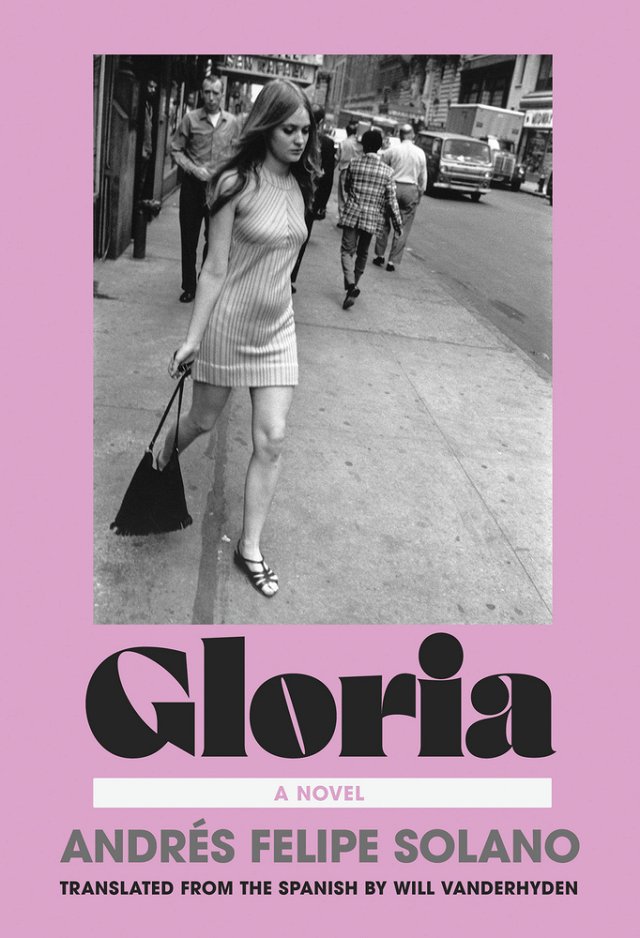

Near the conclusion of Andrés Felipe Solano’s 2023 novel Gloria, newly translated to English by Will Vanderhyden, the unnamed narrator recalls poring over photographs that his mother took when she lived in New York City as a young woman. “I looked at them obsessively as a child,” he writes, “hoping they would reveal the secrets of her life in the United States.” Gloria is based on the life of Solano’s actual mother, and one of her photos from September 1970 is reproduced as a visual coda to the novel, attesting to its autobiographical bona fides. Yet the Colombian author’s story is never constrained by these concrete traces of his mother’s life, and in fact two of the novel’s turning points involve visual keepsakes being lost forever, making Solano’s fictional account as hypothetically true as any other. But he isn’t necessarily searching for veracity. He is simply “supposing,” allowing episodes from his mother’s life, his own life, and their shared time together “to overlap, to intermingle,” to become a sudado de recuerdos where photographs are but one ingredient.

The novel, which marks Solano’s English-language debut, visits a handful of moments over nearly five decades but keeps returning to a roughly nine-hour period beginning in the late afternoon of Saturday, April 11, 1970, and continuing until just after midnight. On that day, the twenty-year-old Gloria goes to see her first concert, which happens to be Sandro de América at Madison Square Garden. Sandro was the first Latino to play the Garden, and his popularity at the time is evidenced by a comparison to Elvis: Sandro is “their King, not the King of the gringos.” The lead-up to the concert finds Gloria recounting the quotidian details of her life at the time, living in Elmhurst, Queens, working at an Agfa photo processing lab, and dating a boy who goes by the nickname Tigre. After the show, Gloria, Tigre, and their friends Carlota and Torero go to a diner, walk through Times Square, and head back to the boroughs for a nightcap.

This incarnation of Gloria is an ingenue, a little fish in the big pond, slowly picking up bits of English: “It’s all an adventure and New York hasn’t knocked her down yet.” She doesn’t smoke, has never been drunk, and is continually scandalized—though seemingly cautiously intrigued as well—by the way the city wears sex on its sleeve. By the time Gloria is in her fifties, she works for a lingerie shop, where she “often finds herself in situations others might avoid,” situations where “strangers lower their defenses and open up to her.” Questions about the presentation and sexualization of bodies is one of the few through lines in Gloria’s life, but it is otherwise unremarked upon by the narrator, and I would have welcomed more insight into whether she sought out this late-in-life position or merely fell into it because it was a job.

Solano has done his research and you can see it on the page—namedropping businesses that were around fifty-five years ago (shout-out to John’s, which has been in Queens since 1965) and alluding to timely current events, like the launch of Apollo 13, the recent-ish Stonewall riots, and the imminent opening of the Playboy Club, where Gloria’s friend Carlota has landed a job. He also drops mentions of automats, Times Square peep shows, and Moondog, an eccentric NYC musician who posed for the photo with the real-life Gloria that appears in the novel.

Other episodes in the story touch on the childhoods of the narrator and of his mother, as well as their later-in-life time together. Gloria grew up in material luxury, but her young life was defined by intangible loss. Her father, a well-off Bogotá lawyer, was gunned down when she was just three years old, and her mother, who to Gloria’s mind “never loved her,” soon packed her off to boarding school. When the narrator is a child, his family is vacationing in Miami after visiting Walt Disney World and his parents’ marriage is already shaky. Gloria ultimately won’t get divorced for more than twenty years, but her son empathizes with his mother: “It should be, it should be possible for her to escape this marriage, which little by little had been becoming a second boarding school.” In this scene from 1983, the family’s hotel room is robbed and their video camera, with their vacation memories on it, is stolen—the second time in the novel when Gloria’s memories vanish, the first being when she loses her camera at the concert. The narrator also recalls his own six-month sojourn in New York in 1998, when he, too, was twenty years old and doing the things young adults in New York do, though the recollections are rather dull, limited to a single night out at a club (the long-gone Element) with a Hungarian girl.

Vanderhyden’s translation has plenty of lovely moments, such as “The seed of disquiet, discovered in the center of her chest when she got up that morning, has grown into a tangled mess of tachycardia and burning palm trees.” A few particularly deft decisions also deserve highlighting. One is the handling of a neat moment between Tigre and Torero where Solano uses the fact that Torero, who is Uruguayan, would not understand specific Colombian words. When Tigre mentions the concept of “verraquera,” Vanderhyden retains that word in Spanish, allowing Tigre’s explanation that it means “Brio. Desire. Muscle” to work for both Torero and English-speaking readers. By doing so, Vanderhyden aptly draws attention to the sort of machismo that both young men seem to relate to and exhibit, and one that accounts for a growing tension between Tigre and Gloria. Another stellar translation moment comes late in the novel when Gloria is thinking about a relative who suffered some “hard knocks.” This is such a distinctly English/American idiom that it led me to check the Spanish-language version of the novel. Turns out that Vanderhyden derived the phrase from “pobre de solemnidad,” literally something like grave poverty, which would have been much less evocative and shows just how valuable a skilled, attentive translator can be.

In 2014, Solano told McSweeney’s that while his fiction doesn’t always include a crime, it does always include “at least two things that I associate with crime fiction, or what we refer to in Spain and Latin American as the novela negra: there’s someone who is desperately searching for something, and there’s the sensation that, at any moment, a violent situation might erupt.” That latent sense of violence certainly runs throughout Gloria. Part of this feeling derives from the robbery in Miami, the past murder of Gloria’s father, and Tigre’s explicit mention that he’s “seen three robberies, one with a pistol.”

While the presence of these harbingers of violence are justified in the end, the novel as a whole is much more concerned with the desperate searchers, starting with Gloria, who is seeking answers about her father’s death, her mother’s standoffishness, and the “exhausting” nature of love, which at one point is described as “an endless game that consists of knowing how to keep your balance to avoid falling into the abyss.” The first of these has scarred her the most deeply, however, leaving her with the knowledge that “sometimes a future that never took shape weighs more heavily than any past.” While Gloria is a novel based on individual memories, it has a universal familiarity as well—never more so than in showing these lives that tragedy and violence might interrupt at any moment.

Cory Oldweiler is an itinerant writer who focuses on literature in translation. In 2022, he served on the long-list committee for the National Book Critics Circle’s inaugural Barrios Book in Translation Prize. His work has appeared in the Boston Globe, Star Tribune, Los Angeles Review of Books, Washington Post, and other publications.

Up Next

Traducir las palabras talismánicas de Frank Stanford | Una conversación con Patricio Ferrari

More Reviews