Glittering Fragments | A Conversation with Jack Pendarvis

Interviews

By William Boyle

I was living in upstate New York in the fall of 2005 when I picked up an issue of Paste Magazine and read George Singleton’s review of Jack Pendarvis’s first story collection, The Mysterious Secret of the Valuable Treasure. I immediately bought the book and became a fan. I had no idea that, three years later, I’d wind up moving from New York to Oxford, Mississippi, and meeting Jack. He and his wife, Theresa, had just moved to Oxford from Atlanta; Jack had a visiting writer gig (the great Barry Hannah had brought him to town). We hit it off pretty quickly, talking movies and books and music over drinks at City Grocery bar. I took a class with him, the most memorable one in my graduate school experience. Where else could you read Loretta Lynn’s Coal Miner’s Daughter, Lynda Barry’s One Hundred Demons, biographies of Billy Strayhorn and Sun Ra, and watch Gold Diggers of 1933 and Stolen Kisses? Where else would the teacher bring in his pal Bill Taft (from one of my favorite bands, Smoke) to play a live instrumental score during a screening of Un Chien Andalou? Nowhere else. It was just the best.

In his introduction to an anthology of writing by the great Nashville Scene film critic, Jim Ridley, Steve Haruch writes: “The writer and theology professor, David Dark . . . once remarked that the lesson Jim taught him was that ‘you can find your voice by loving things.’” Jack taught me that same lesson. He’s been a great hero and pal. He’s one of my favorite writers and one of my favorite people. His books include Your Body is Changing, Awesome, Movie Stars, and Cigarette Lighter, and he’s written for a number of animated shows, including Steven Universe Future, SpongeBob SquarePants, and Adventure Time, for which he won two Emmys.

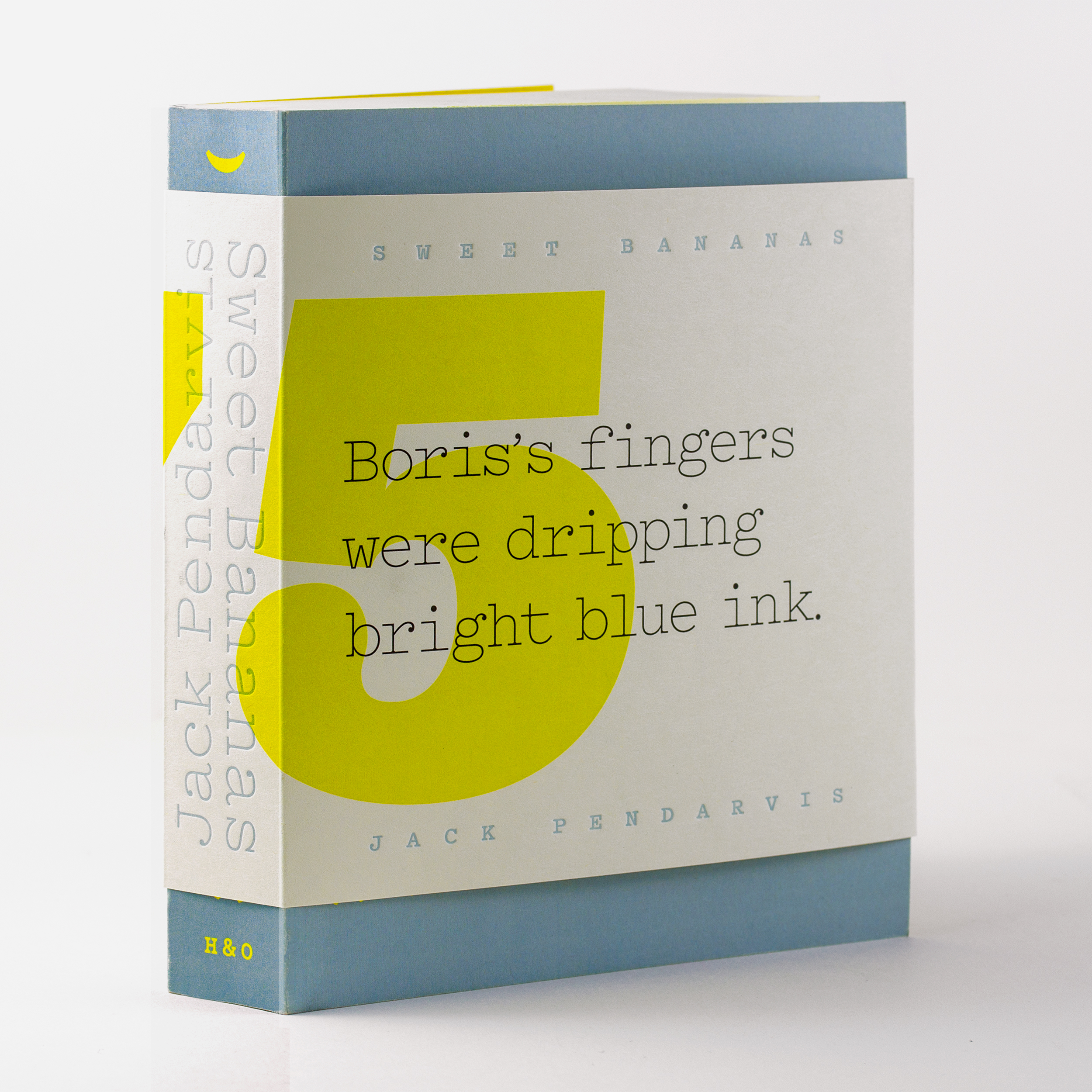

Hingston & Olsen has just published Jack’s newest book, Sweet Bananas, in a limited run of 365 copies. It’s a series of dialogue-driven vignettes about a married couple, Boris and Clementine, going about their daily life. Watching movies, cooking food, feeding their cats, looking out the window, going into the world to do things they don’t really want to do, and—most of all—being together. Surviving together. It’s a joyous and hilarious love story. Each copy is wrapped in a unique letterpress-printed dust jacket signed by Jack. Real love has gone into this book at every turn. I can’t recommend it enough. I was lucky enough to get to ask Jack a handful of questions about Sweet Bananas.

William Boyle: Can you talk about how Sweet Bananas started? What various stages did it go through before reaching its final form? At some point, I think you adapted it into a script and there was some talk of making it into a film. Was there also a graphic novel adaptation in the works?

Jack Pendarvis: Well, first I wrote it just the way it is. I sat down and wrote the first paragraph and thought, “That’s a whole thing.” I’m always chasing that Lydia Davis feeling . . . enviously wondering how she knows when to end something. I still haven’t figured it out. But I knew the first chapter was done. And I saw how short it was. And I thought, “I can write a bunch of these!”

Tom Franklin had enjoyed a short story of mine called “Marriage,” which was similar in tone. So, as highly suggestible as I am, I thought, Hell, I can make a whole book like this. If Tom likes something once, he’ll love it if I do it over and over! This was my theory. From the first, I thought of it as a present for Theresa, which is what kept me going on it.

My main inspiration was the Mary Robison novel Why Did I Ever, which consists of hundreds of very short sections. I settled on the number 365, because I thought it would give the illusion of structure. Robison’s book actually has a great deal of drama in it, in the narrator’s situation and relationships, but I kind of wanted to write something that was drama-free. Which I’m sure is a big selling point!

Now, nobody really knew what to do with this book, so, yeah, I wrote a script version. If there is anything better than a drama-free book, it’s a drama-free movie. There was actually some talk about making it, but that fell through for tragic reasons. Kent Osborne and I discussed turning it into a graphic novel, but Kent wanted to come down and draw me, and draw Theresa, and draw our house, and make us act out the book, I guess. And I didn’t want any of those things to happen. I mean, it’s fun when Kent visits! So I wouldn’t have minded that part. But I didn’t want to model for him! So we didn’t do anything more than talk about it.

It was Mary Miller who really encouraged me to stick to the book the way it was. I lucked into finding a publisher who understood it, too. It only took six years. I couldn’t have found anyone who would have paid more attention to the book than Hingston & Olsen, nor anyone who would have worked so hard to make it special. Even I can tell the paper is luxurious, for example, and I don’t know anything about paper. I tried to answer your question briefly, but this answer is longer than the book itself.

WB: Ha. You call it drama-free, but it’s full of so much everyday drama, which is one of the things I love most about it. The drama of a relationship, of routine. This is primarily a joyous book about marriage, but there’s also a lot of fear. Fear of disease and death. Fear of intruders and strange noises. In a way, Boris and Clementine always seem like they’re under attack. Their relationship anchors them. It strikes me that love is really just about overcoming fear together. Did you think about this as a love story?

JP: Two things about that question. First, I was going to tell you my theory about your books, which is that they are all about love. Do you think that’s true? I was going to ask you about that when we finally sat down somewhere in person to talk about Shoot the Moonlight Out. The other thing is that those were the exact words Mary Miller used to encourage me about Sweet Bananas. I said people weren’t getting it, and she said, “It’s a love story.” Like, what’s not to get? Such was her tone. As for the other part of your question, I think you’d be crazy not to be afraid of disease, death, intruders, and strange noises. “The drama of routine”—ha ha ha, remind me not to ask you for a blurb!

WB: Well, I guess I’ll steal a line from John Cassavetes here: “That’s all I’m interested in—love. And the lack of it. When it stops. And the pain that’s caused by loss of things that are taken away from us that we really need.” I think about that all the time while I’m writing, more and more lately, so I think Shoot the Moonlight Out is probably the book of mine that’s most about love. Bringing up Cassavetes seems fitting. There’s a reference to Love Streams in Sweet Bananas. I actually thought of that film—one of my favorites—quite a bit as I was reading. Is Sweet Bananas your Love Streams?! Also, can you talk a little about the role that movies generally play in the book? It feels like a love song to movies, too.

JP: Sure, let’s say Sweet Bananas is my Love Streams. Who’s going to fact-check that? I defy anyone to disprove it. You know, it’s a fairly disrespectful shout-out to Love Streams in the book. I believe Boris says “They’re just babbling.”

Well, Bill, I would argue that A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself and City of Margins are also about love, just to name two of your books. Maybe it is a direction you have been moving in. Also, it is a big love, like worldwide human love, not just a couple falling in love. You’re a philosopher of love!

As for movies, I think you and I are alike when it comes to movies. Your characters talk about movies a lot. You and I watch lots of movies of all different kinds. It can’t help but spill over into the work, like how Jane Austen was probably playing whist all the time. Whist was her version of the movies! And people were probably like, “Hey, Jane, what’s with all the whist in your novels?” And she was like, “I love whist!”

WB: Thanks, man! Yes, I guess all of my books really are about love. You’ve convinced me! Speaking of love, I also love great food writing and there’s lots of great food writing in Sweet Bananas, from staples like oatmeal to more adventurous meals. Boris and Clementine are often talking about what to eat and where to eat, and we often read about them preparing meals or dissecting meals after they’ve eaten. There’s also a fair amount of booze. This book made me hungry, and it made me want to drink! I love that. Who are some of your favorite food writers? What are some of your favorite books on food? Did anyone or anything particularly influence your approach to writing about food? Also, Boris says he hates artichokes. Is this just a Boris thing or do you hate artichokes? If it’s you, I’m gonna turn this interrogation lamp on and we’re going to get to the heart of this. (Oh man, as I typed that I realized I was making an awful joke—the heart of this artichoke thing—but I’m leaving it in).

JP: So, as you know, Hingston & Olsen sent me all of the 365 different dust jackets to sign, and each dust jacket features a different sentence from a different chapter of the book. Theresa was standing over my shoulder, watching me sign some of them, and she said, “Huh, a lot of these are about food.” I didn’t realize it while I was writing it. I guess because I was writing about daily life, and eating is something people try to do every day, it just came about naturally. This reminds me of when you and Mary Miller and I were at the City Grocery bar once, and she said to you (this will almost be an exact quotation): “Bill, let me ask you something. Your characters eat a lot but they don’t go to the bathroom.” That’s when The Lonely Witness had just come out, and I said, “The Constipated Witness.” Ha ha, we all had a big laugh. You said that the book took place over a short span of time, and then Mary said that her characters go to the bathroom constantly. “The New York Times commented on it,” I believe she said, referring to the bathroom habits of her characters.

Your question about food writing . . . my first mentor as a writer was Eugene Walter, who wrote about food a lot. He’s not to be confused with a playwright of the same name who died in 1941. Anyway, I guess Eugene planted in my mind early on that food was something worth contemplating and describing.

I’ll tell you about the first piece of food writing that intrigued me. I was just a kid. Many years before I met Eugene. I can’t figure out where I read it. It was in a magazine that belonged to my mom or grandmother. A couple of people drove across the country eating hamburgers from fast-food chains, and they thoughtfully dissected the qualities of these hamburgers in a way that thrilled me. For whatever reason, I read that article over and over. Something about paying such attention to such an everyday thing. Also, maybe, the idea of hitting the road. I have no idea what magazine that was in, or who wrote it, but I can still kind of smell the magazine. These hamburger writers were my Jack Kerouac, ha ha! Speaking of which, Jack Kerouac is constantly writing about hamburgers and pie and ice cream. Anyway, perhaps one of the readers of Southwest Review will kindly track down that article in a “women’s magazine” of, I assume, the early-to-mid-1970s. I’d like to read it again and find out what I thought was so damn intriguing. Maybe I just loved hamburgers.

That reminds me of my friend Jason Polan, who died last year. He made a newspaper about hamburgers—a physical object of cheap paper and newsprint. I did a piece about our local hamburger place, Handy Andy, for that. Also, once Jason had me contribute anonymously to a pamphlet extolling peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. It was like a little, plain brochure, and I guess he just left it around New York City for people to find. That’s the kind of art I like.

About artichokes, I don’t think I care for them. Mostly I encounter the marinated artichoke hearts that come from a jar. If I find them in a salad, I pick them out. And in its natural state, an artichoke is too complicated for me to handle. Theresa likes the roasted artichoke they have at Tarasque, a local restaurant. I seem to recall some artichoke dip I enjoyed at some point in the distant past. In that case, the artichokes had been pummeled beyond recognition. How about you, Bill? What’s your take on artichokes?

WB: I’m a fan of artichokes! They make me think of my grandmother. I’m mostly just a fan of the way she made them, something I’ve never quite been able to get right, and I remember eating them in her kitchen. I guess it’s all about nostalgia for me. I’m nostalgic for my grandmother’s artichokes! Who knew? I don’t get them often these days, and I’m also not a fan of those marinated artichoke hearts. I bet no other interview that’s not specifically about artichokes has ever gone this deep on them.

I remember that conversation with Mary; I’ve since become preoccupied with my characters’ bathroom habits, thinking Mary won’t buy this if I don’t have a character stop to drop a squirt. I want to find that hamburger article! And I’m so sorry about Jason Polan—I discovered his work thanks to you.

I have one last question. You’re a great songwriter, too, and there seem to be some echoes in Sweet Bananas of the knockout song you wrote for Kelly Hogan, “We Can’t Have Nice Things” (though that song is ultimately darker). The structure of the book feels pretty musical to me—I realize that by referring to it as a love song, I was building on that feeling. What’s this book’s relationship with music? What were you listening to as you worked on it? Did any specific songs or records influence its tone, aesthetic, or structure?

JP: I’m glad we had this talk about artichokes. I certainly didn’t mean any disrespect to your grandmother. I know this was supposed to be your final question, but I have one more for you, which is, how did your grandmother prepare the artichokes?

A small correction: I wrote just the lyrics for that Hogan song. The music was written by Andrew Bird. It’s funny you should ask about music. Not funny, because I know music informs your work in a big way, which is just one of the things I love about your books. Anyway, when Sweet Bananas was finally coming out, I tried to put together a playlist of music that was in the book, and I realized there just wasn’t very much. The country singer Jim Ed Brown died while I was writing it, so his song “Pop a Top” wound up in there. There is a discussion of The B-52s’ hit “Love Shack.” At one point, Boris and Clementine are doing pantomime while listening to a compilation I highly recommend, The Roots of Chicha (Psychedelic Cumbias from Peru). I believe Boris is going to put on some “piano music” in one chapter, by which he probably means Schubert or Schumann. I was disappointed as I went back through and saw how little music is actually in the novel.

Come to think of it, though, I did describe Sweet Bananas to our friend Ace Atkins in musical terms. I think of Sweet Bananas as a pop album with a lot of short tracks on it, rather than some ambitious, complicated fugue or symphony. Maybe I would compare it to Get Happy!! by Elvis Costello, only because that LP had ten tracks on each side, which was overwhelming at the time. I feel like my vinyl of Get Happy!! had liner notes by the producer, Nick Lowe, assuring the consumer that filling each side in such a devil-may-care manner would not affect the sound quality. Everybody was scared! Or maybe it’s like Melt-Banana’s misleadingly titled 13 Hedgehogs, which crams fifty-six tracks onto one CD, or that Residents album where each song is exactly a minute long. Or, wait, that album by They Might Be Giants with the big medley of snippets designed for listening on shuffle. I had it on cassette, so I never got to experience it as They Might Be Giants intended, ha ha! Who cares? Take all the worst aspects of those albums and mix them all together and turn them into prose and voila! Sweet Bananas.

Yeah, I was listening to Schumann at the time I was writing it, and he had certain piano works that seemed to consist of glittering fragments that kind of fizzled out and fell apart in a beautiful way. That’s something to aspire to, I think.

In conclusion, I’ll repeat my request that we end this with your grandmother’s artichoke recipe, as best as you can recall it. Thanks, Bill!

WB: Oh man, I don’t have her recipe. I wish I did! The truth is she probably didn’t do anything special. That is, nothing very complex. She’d get artichokes up at the market and boil them with salt, maybe a little olive oil and garlic. It was just the alchemy of that kitchen. Those old pots. Her hands.

I love that you thought about Sweet Bananas as a pop album. I don’t know how you feel about Guided By Voices, but I thought of them a bit as I was reading. I remember hearing a song like “The Goldheart Mountaintop Queen Directory” for the first time and being blown away that it was so short, that it felt like a vignette or fragment; that it seemed to work against every convention of what a pop song needed to be or do, instead choosing to dazzle quickly and get the hell out of there. Paul Westerberg’s 49:00 came to mind, too. I love that line about Schumann so much. Thanks for doing this, Jack!

JP: You’re welcome, Bill. I just popped on because I suddenly remembered that the Beach House record Depression Cherry makes an allusive appearance in Chapter 274. I was like, “Is that important?” Anyway, I wish I had thought to compare myself to Guided By Voices instead of They Might Be Giants. What a loser!

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out (forthcoming November 2021), all available from Pegasus Crime. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.

More Interviews