Heavy Metal Magical Realism | A Conversation with Max Hipp

Interviews

By Tyler Keith

By day Max Hipp is a Mississippi writer and educator, but by night he’s a straight-up guitar god. Like many of the all-timers, he hasn’t sold millions of records, nor is he known outside the tri-state area, but I’ve seen him play a mean version of Slayer’s “Raining Blood.” Watching him onstage, you know his guitar playing began as a teenager banging it out in some basement, surrounded by posters cut out of Hit Parader magazine. Years of woodshedding while his parents beat on the door.

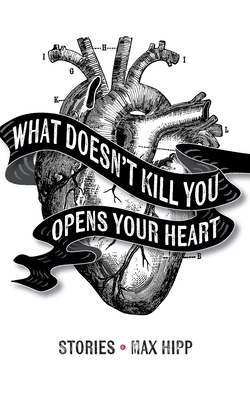

Max Hipp (real name!) brings the same heavy metal mentality and DIY discipline to his debut collection, What Doesn’t Kill You Opens Your Heart. Hipp’s stories can hammer you with the fierceness of a “Fast” Eddie Clarke guitar lick or slay you with the tenderness of a B-side ballad. And he never shies away from hard truths. His characters’ lives are fucked up—so is yours—and he doesn’t leave out the dark thoughts. You know the ones.

Full disclosure: I’ve played in a band, the Apostles, with Max for over a decade. We’ve had many long rap sessions on the road and in dark bars over the years. This particular conversation occurred on the eve of the release of What Doesn’t Kill You Opens Your Heart, published by Cool Dog Sound.

Tyler Keith: When did you become interested in writing?

Max Hipp: My writing started in junior high, as heavy metal lyrics. I wanted to write lyrics like Slayer. Their songs were like horror movies. They wrote in first person from the POV of killers, demons, and other meanies, which fourteen-year-old me thought was the greatest achievement. Eighties Metallica lyrics were a big deal too. I liked that reactionary people in the South were afraid of this music and these bands. So I tried to write like them and played in metal bands through the nineties and beyond.

I didn’t get serious about writing until college. I took an intro to lit course and read short stories and poems by Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner, Yeats, and Eliot. Until then I’d only read what was assigned in school, didn’t read anything for pleasure. I’d tried commercial fiction but it never appealed to me. But I loved movies and saw almost every 1980s action movie in the theater, and that became my main source of story. As a child, I remember reasoning that it wasn’t worth my effort to read a book since I could watch a movie in only two hours. So the Modernists from that class showed me that writing could be an artistic thing. I didn’t know anything about art, didn’t come from an artistic family. Didn’t go to museums or anything. But I noticed the effect of these writers on me, how they had me thinking more deeply about life, and myself. These complex psychological characters they depicted made me feel less alone in the world. I didn’t know it yet, but I was a complex character too.

After I graduated with an English degree, I worked in a factory for about nine months until I decided grad school would beat the hell out of working in a factory. Once I was in the grad program, I took a workshop with Barry Hannah. He was the first writer I’d ever met and the first artist. He didn’t teach craft so much, but you went to class each week just to hear him talk. His conversations with the class about our writing felt like jam sessions in the practice room. His approach to language, just the way he spoke about writing, made it feel like anything was possible. He was the first person who ever took the things I wrote seriously, which is about the best gift you can give a new writer. Then, in a stroke of luck, Ole Miss started an MFA program, and I transferred in, on the strength of my heavy metal lyrics, I guess. Completely naive and ignorant of craft. But writing was the most difficult and wildest thing to me. I figured I’d give it ten years. Then I gave it ten more. It appears I’m a lifer now.

TK: In the story “Cliff Burton Rules,” the main character, Sammy, says, “Through metal I am cleansed and tempered.” Metal is his lifesaver and shield from an uncaring world, and an inspiration for his budding imagination. I think this story may be the first example of Heavy Metal Magical Realism. Did the story materialize from your own teenage metalhead experience? You mentioned earlier your fascination with Slayer lyrics. I sometimes think hate is an underrated artistic motivator. Like your character says, “If you want blood you must sacrifice.” Talk about this story.

MH: Ha, I like this idea of Heavy Metal Magical Realism. Yes, Sammy is close to my heart. He taps into something important to me as a kid, the way metal provided a sense of agency and belonging in a world that seemed scary and chaotic. Even if metal lyrics are about hobbits and dragon decapitation, it’s a world where the violence feels campy or formal and within boundaries. It creates a space where you can feel in control. I root for my teenage characters because they’ve got the most to lose. Hate is a motivator for Sammy, especially in writing some mean metal lyrics, but it’s less about hate and more that he’s afraid to feel love because, in his experience, love might hurt him. Hate can protect him from what hurts. That said, I think Sammy’s going to turn out just fine.

TK: In the story “How to Pick Up Beautiful Women,” each chapter starts with a new line for picking up women. For example: “Hi, a beautiful woman like you should have a great evening, give me a chance to make that happen. May I join you in a drink?” The main character, a man who teaches composition at a junior college, uses these lines throughout the story, while simultaneously correcting the sentences. How did you come up with the idea for this story?

MH: The pickup lines are from John Eagan’s real book with the same title as the story. Will Little, the narrator, takes pains to credit him and cites when he’s quoting, like the diligent and fastidious composition teacher that he is. Of course, the book inspired the idea for the story. The pickup lines gave it a structure where I could imagine the scenes and situations. I used ten of them but later cut some in revision because the story didn’t need them all. The words of John Eagan and Harville Hendrix really resonate with Will Little.

TK: You mentioned Barry Hannah earlier. He’s considered a master of the short story in some circles. I see similarities in your style, especially the voice—for example, in your lead-off story, “Stump Girl.” What did you learn from him?

MH: I’ll take that as a compliment! Hannah is a singular voice. From his class, I mainly learned “Beginning, middle, end, thrill me.” Also, putting two characters in a room to see what happens is still a good way to get a new story started for me. The voice stuff I must’ve gleaned subconsciously from reading him because I never sat down to emulate or study what he was doing. I never went crazy on it, like that meme of Charlie in It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. I respect the magic of fiction. If you look at it under a microscope, there’s nothing holding anything together but a cloud of dust.

TK: Some of your characters, specifically the junior college English professors, remind me of the overeducated, helpless characters in Flannery O’Connor stories. How influential is her work on your stories?

MH: I can see it, but O’Connor’s a lot meaner to her characters than I am! She was probably the first writer I read who depicted tragedy with deadpan humor. The way her people spoke and the rhythm of her narration sounded familiar too, like the voice of a terrifying grandparent.

TK: Do you have a favorite short story or one that really delivers everything you want in a story?

MH: Picking a favorite story is like choosing a favorite song, which is impossible. But I enjoy lots of short stories by so many writers I’ve found in books, journals, and across the internet. People like Kathryn Scanlan, Ashleigh Bryant Phillips, Alan ten-Hoeve, Amy Hempel, Mary Miller, Jayne Anne Phillips, K.C. Mead-Brewer, Steven Dunn, and Bill Merklee. They deliver. (I’m too exhausted to give an exhaustive list.)

Tyler Keith was born and raised in the Panhandle of Florida. He moved to Mississippi at eighteen and has been there ever since. He’s spent the last thirty years playing in bands (the Neckbones, Tyler Keith and the Preacher’s Kids, Tyler Keith and the Apostles, and Teardrop City) making 14 albums and touring in the U.S. and Europe. In 2013 he wrote and performed in a musical play called “the Outlaw Biker.” His first novel, The Mark of Cain, appeared in 2022.

More Interviews