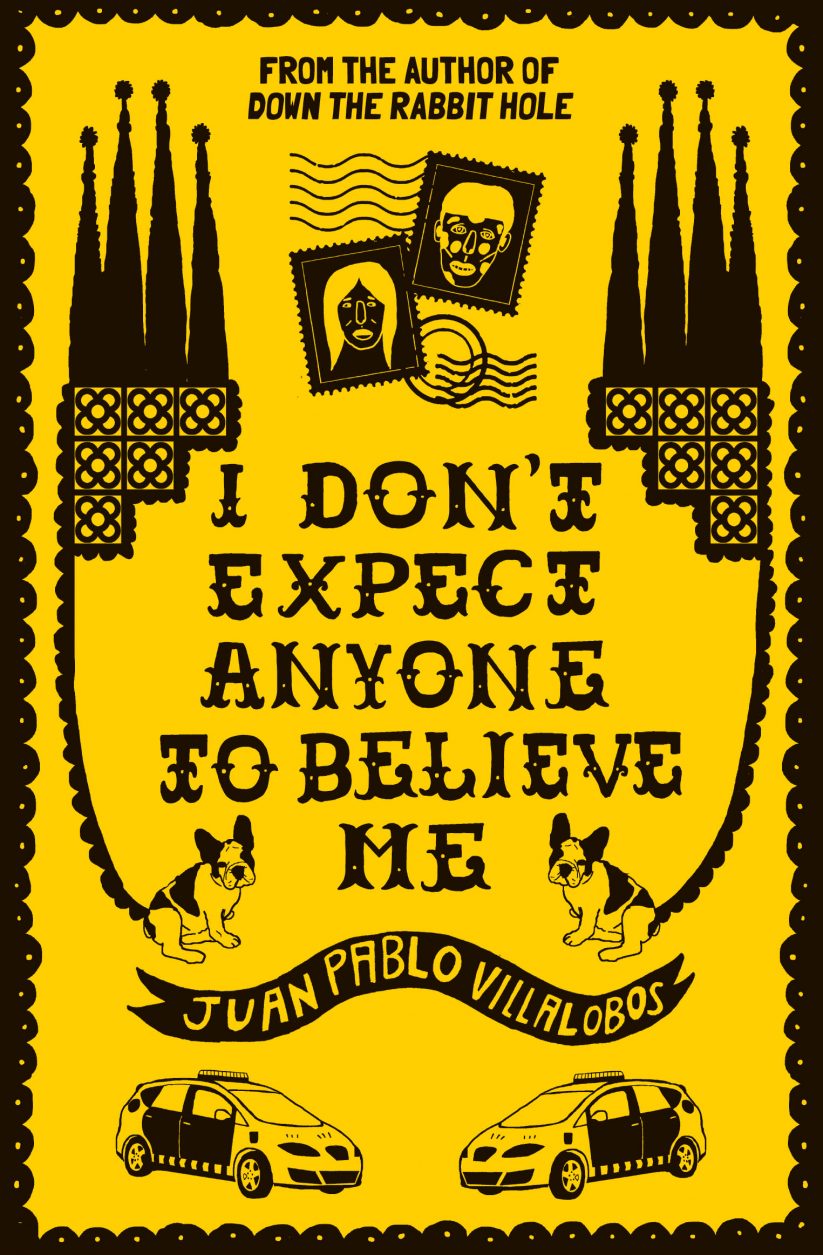

A Stylish Blend of Comedy and Crime | Juan Pablo Villalobos’s I Don’t Expect Anyone to Believe Me

Here’s a pitch for a novel: a plucky band of young nerds gets mixed up with some criminals and things go wrong from there. There’s a murder, and the nerds are forced to flee the country. At the end they disappear, never to be seen or heard from again. It’s Stranger Things meets Uncut Gems, which explains why so many people were taken with The Savage Detectives.

Since his death in 2003, Roberto Bolaño has inspired the kind of reverence usually reserved for dead rock stars. The Savage Detectives is that rare book that is both a literary masterpiece and a bestseller. So it makes sense that an author with this sort of crossover appeal is ripe for parody.

If Bolaño’s premise—a young writer drawn into a life of crime—struck you as ridiculous, I Don’t Expect Anyone to Believe Me is the book you’ve been waiting for. (I am not that reader, but I too am in luck because it’s the spoof I didn’t know I wanted.) The basic setup is the same. Juan Pablo Villalobos names his hero after himself and sends him on a globetrotting adventure. His experiences at home and abroad provide material for an autobiographical novel with the same title as the one you are reading. And for the cautious reader who thinks I’m reading too much into this: care to guess what book his girlfriend, Valentina, reads along the way?

I Don’t Expect Anyone to Believe Me does for The Savage Detectives what The Big Lebowski does for The Big Sleep, and there’s more than a dash of the Dude in the narrator Juan Pablo. The first part takes place in Mexico, where his cousin involves him in a shady business deal, and the second part is about Juan Pablo trying to extricate himself from said deal while studying abroad in Spain. Early in the novel, he describes a meeting with a so-called investor: “My naivete in business matters was so great that I didn’t know investor meetings were held in the basements of lap-dancing clubs and with one partner tied to a chair, true kidnapping-style.” Much of the humor comes from the fact that he’s a gullible guy in over his head, but what starts as an irreverent crime comedy turns into something more than pure farce.

The novel also works as a slashing satire of overeducated, bookish types. Thanks to his no-good cousin, Juan Pablo is implicated in an international crime ring. The ringleader, while holding the cousin hostage, asks what Juan Pablo studies in school. “The limits of humor in Latin American literature,” the young scholar declares cheerfully before launching into a lengthy disquisition on political correctness. His over-eager delivery earns eye rolls all around, though in some ways he’s just as clueless as those he lectures. Later on in Barcelona, he fails to recognize his contact—known simply as “Chinaman”—because all Chinese, he says, “look the same to me.” He mistakes another member of the crew—a Pakistani named Ahmed—for a drug dealer. The two form an unlikely bond with a dog that witnesses a murder, at which point Ahmed asks how a smart kid like him fell in with this crowd.

The truth is that we readers don’t look to literature for guidelines for our behavior in reality. Nor do writers, either. All we readers and writers want is to perpetuate a hedonistic system, based on self-indulgence and narcissism. All a true reader ever wants is to read more. And a writer to write more. And we academics are the worst: scavengers who want to extract some bit of existential meaning from all this shit.

It’s fair to wonder if Juan Pablo is capable of having this much self-awareness. Regardless of whose voice it is—the author’s or the narrator’s—one thing is clear: Villalobos gives zero fucks for the pieties of literature with a capital L. Cue the applause.

Warning: this book contains politically incorrect jokes. It’s highly problematic, as they say, but funny as hell if you have a sense of humor about these things. The twist is that the punch line doesn’t reinforce stereotypes; it subverts them. For example: “There’s a Mexican, a Chinaman and a Muslim and they’re meeting with a Mexican mafioso in the office of an abandoned wine store in Barcelona, except the Muslim isn’t exactly a Muslim, he’s a Pakastani atheist.” That last bit—the part about the atheist—is what keeps this from being an anti-PC crusade. Not only is Ahmed an atheist; he’s gay with a degree from Yale. Villalobos hints at what he’s up to when he has someone tell Valentina, “you got this preconception about criminals being poor people, Africans, gypsies.” Which all goes to show that criminals come from every walk of life and every corner of the globe.

In the same cheeky spirit, the novel takes a swipe at the macho posturing of The Savage Detectives. In Bolaño’s world, the women are often stuck in the background so the men can get on with their adventures. Initially, the same is true here, with Juan Pablo as the adventure-seeking hero. For anyone who has read The Savage Detectives, what happens to him in the end comes as no surprise. What is surprising, though, is that the real hero of Villalobos’s novel is Valentina.

And finally, Daniel Hahn deserves serious props for his masterful translation. Part of what makes the book so funny is the lively voices of its characters, and Hahn perfectly captures their chatty, slangy, obscenity-laced eloquence. And that’s no small feat, given the many dialects and sprawling international cast.

This is a comic novel with something for everyone—humor, both high and low, with plenty of jokes to go around. Then again, humor described is humor denied, so when I say I laughed my ass off, I don’t expect anyone to believe me.

Robert Rea is the managing editor for SwR.

More Reviews