In this edition of “I Wake Up Streaming,” novelist William Boyle rounds up his top streaming picks for the month of February. The column’s name is a play on the 1941 film I Wake Up Screaming, starring Betty Grable, Victor Mature, and Carole Landis. While the film’s title hits a pleasing note of terror and despair, changing that one letter speaks to the joy of discovering new films and rediscovering old favorites, as well as the panic that comes with being overwhelmed by options.

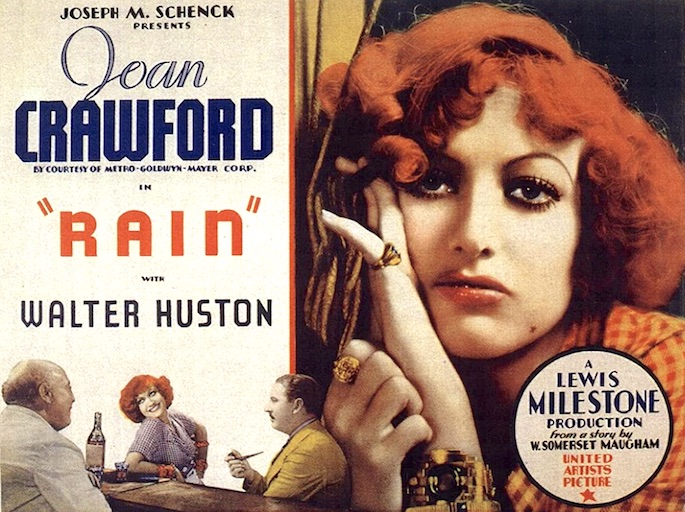

Rain (Kanopy)

The stunning ninetieth anniversary restoration of Lewis Milestone’s Rain, recently released on Blu-ray by VCI and now available to stream on Kanopy, is yet more proof of how essential film preservation and restoration are. The film entered the public domain in 1960 and has been widely available to see in dreadful prints. Grainy. Distorted. When I first watched it, years ago, I certainly responded to the narrative—it’s based on a W. Somerset Maugham short story and the hit play it spawned—and the performances (Joan Crawford and Walter Huston are both revelatory), but so much was lost in the muck. The restoration, conducted by The Library of Congress in association with The Mary Pickford Foundation and produced from the original, uncut ninety-four-minute pre-Code 1932 version (the film was badly butchered into a shorter, neutered version in the late thirties), opens things up in ways I couldn’t have anticipated. Milestone—a great, underrated director with a rich and varied filmography—has style to burn. The elegant camerawork is hypnotic. There are many haunting close-ups, and the camera—even in the claustrophobic setting (a rain-drenched general store/inn)—seems to never stop moving. The story is heated, intense. A boat headed for Apia, Samoa, is stranded in Pago Pago after a cholera outbreak on board. The passengers include Huston’s Alfred Davidson, a buttoned-tight missionary, and his stodgy, sour wife, as well as a flamboyant prostitute, Sadie Thompson, played by an utterly electric Crawford, who’s drawn the attention of the American Marines stationed in the village. Sadie and the Davidsons wind up staying in the same place, a general store and inn run by Joe Horn (Guy Kibbee). Tensions rise when Mrs. Davidson takes umbrage at Sadie’s behavior—she’s drinking and dancing with the Marines in her room. Mr. Davidson sets his sights on saving her soul. Sadie clashes with him. But Davidson is a powerful reformer with political influence, and he convinces the governor to deport Sadie to San Francisco, where she has a murder rap hanging over her head. To say more would be to spoil the drama. Rain is constant, pattering against the roof of the store and falling all around them. The action stays mostly in one place, though it never feels like a restriction. Crawford—playing a role made famous on stage by Jeanne Eagels—is all guts and passion. Those smoky eyes and that voice. The pleasure of watching her stand up to Davidson and the torture of watching her subsequently crumble before him. The film didn’t do well when it was released, and Crawford was apparently displeased with her work—but I’d put it up there as one of my favorite performances ever. And that ending. Wow. Suffice to say that two short years later when the Hayes Code was enacted, such an ending would’ve been impossible. Even now, the ending feels transgressive. Rain is truly one of the marvels of pre-Code cinema.

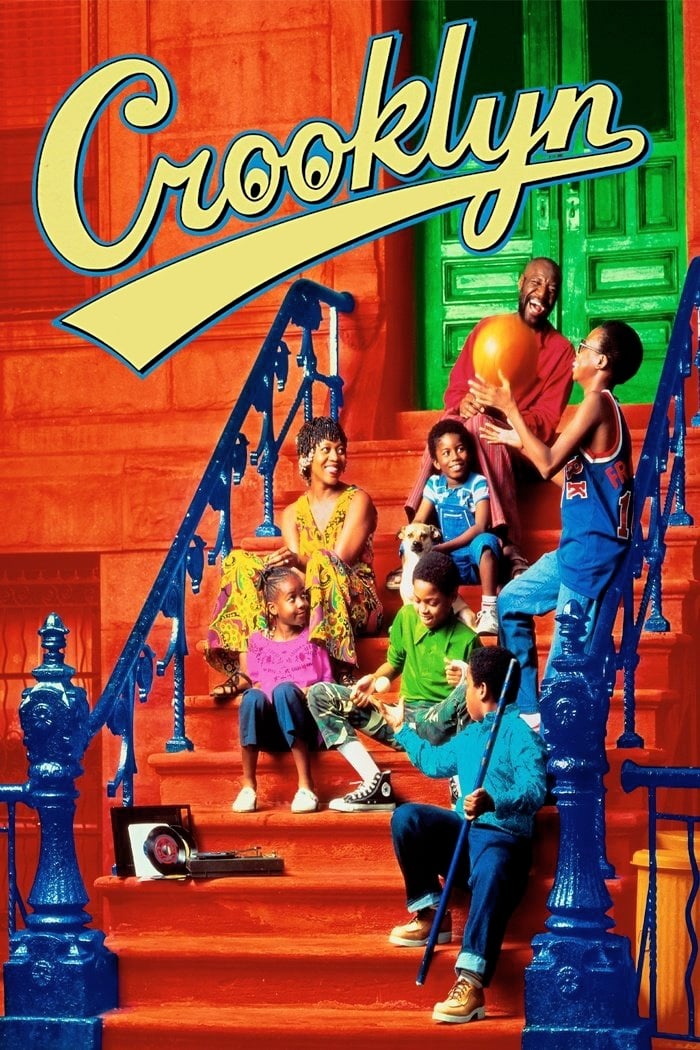

Crooklyn (Peacock Premium)

Picking a favorite film by Spike Lee is a difficult task. He’s been one of my top directors since Do the Right Thing blew me away and changed my perception of the world when I was eleven. Considering its impact, that’d be the obvious choice for number one. Malcolm X is also a masterpiece. I could make good cases for He Got Game and Clockers, and 25th Hour keeps moving up my list. But it’s 1994’s Crooklyn which I always seem to return to. One of the great coming-of-age films of the late twentieth century. An all-timer of a soundtrack. Lee’s most personal and beautiful movie, co-written with his sister Joie and his brother Cinqué. A deeply underrated standout from one of cinema’s most memorable years—it’s astonishing that Alfre Woodard and Delroy Lindo didn’t win awards, weren’t even nominated. The story centers on Troy Carmichael (Zelda Harris), who lives with her parents, Carolyn and Woody (Woodard and Lindo), and her four brothers in Bed-Stuy. Through vignettes, we follow their trials and travails and triumphs over the summer of 1973. The movie just feels like youth. It’s alive with place details. Stoops and hydrants and bodegas and ice cream trucks. Forgotten childhood games. Neighborhood characters like Tony Eyes, Tommy La-La, Snuffy, and Right Hand Man. Lee’s Brooklyn comes fully alive. Crooklyn got a nice Blu-ray release from Kino Lorber in 2020, but it hasn’t been (at least not that I’ve noticed) very present on streaming services, so it was nice to see it pop up on Peacock (which I recently had to subscribe to so I could watch Rian Johnson and Natasha Lyonne’s excellent Poker Face).

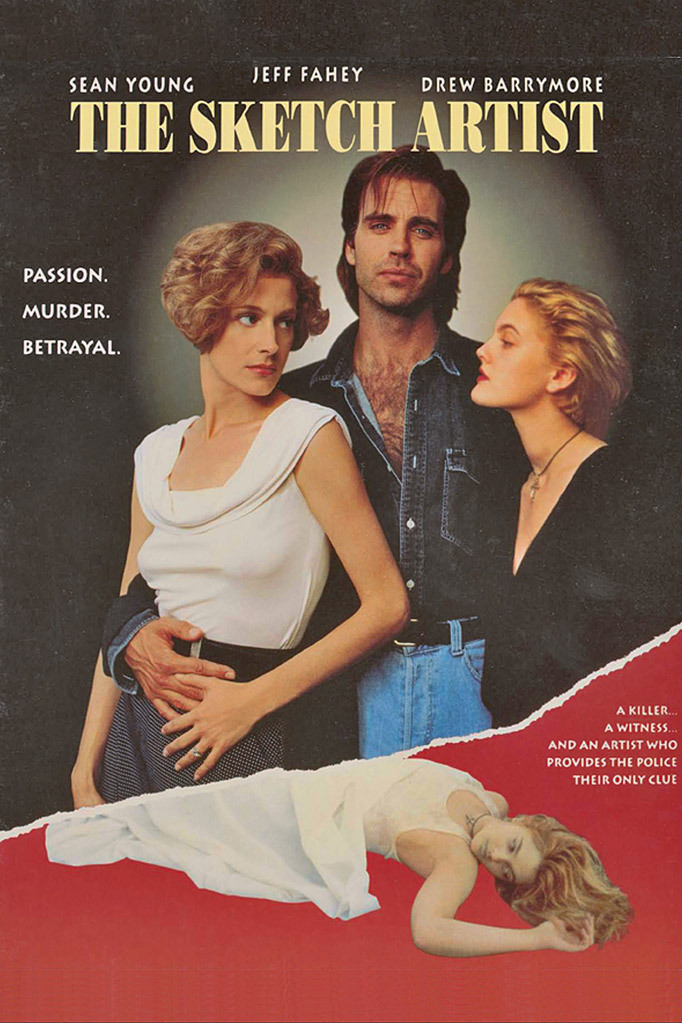

Sketch Artist (Tubi)

I’ve been on a Drew Barrymore kick lately. She was a big deal for me growing up, and I’m especially interested in her early nineties work, those years where she was caught up between the child star she was (who struggled, very publicly, with addiction) and the rom-com sweetheart who emerged in the mid to late nineties. In movies like Poison Ivy, Guncrazy, The Amy Fisher Story, and Doppelganger, she has a different presence. Sketch Artist isn’t really a Drew vehicle—she only appears briefly in it, but she’s what brought me back to it. I saw this made-for-Showtime TV movie once after it originally aired. I didn’t have cable, so I can’t remember the exact circumstances. I either rented it, if it even appeared on VHS, or—and this is the likelier option—I taped it one weekend when I was visiting my old man in Jersey. He did have cable. I’d put a blank VHS in his VCR late at night and just record whatever was on a channel like Showtime that I never had access to. Chances are pretty good that Sketch Artist would’ve been a movie I caught on one of those net-casting missions. Jeff Fahey—with his striking blue eyes, his mullet, and his glorious chest hair—plays a police sketch artist named Jack Whitfield. Drew is Daisy, a messenger who’d been delivering something when she saw a woman emerge from an office where a well-known fashion designer had just been murdered. The woman Daisy describes to Whitfield is a dead ringer for his wife, Rayanne (a smoldering Sean Young), who’d been out of town on a business trip. Whitfield scraps the drawing and makes another one and then begins the process of trying to investigate the crime himself. It’s a solid, grimy neo-noir that could’ve only been this good for what it is in the early nineties. For some reason, I kept thinking it had the tone and feel of an Afghan Whigs song. The real standouts here are all hair-related: Drew’s eyebrows, Fahey’s mullet and chest, Young in Bridget Fonda doppelgänger mode. Sometimes, pals, you just need a dirty little sax solo of a movie to get you through.

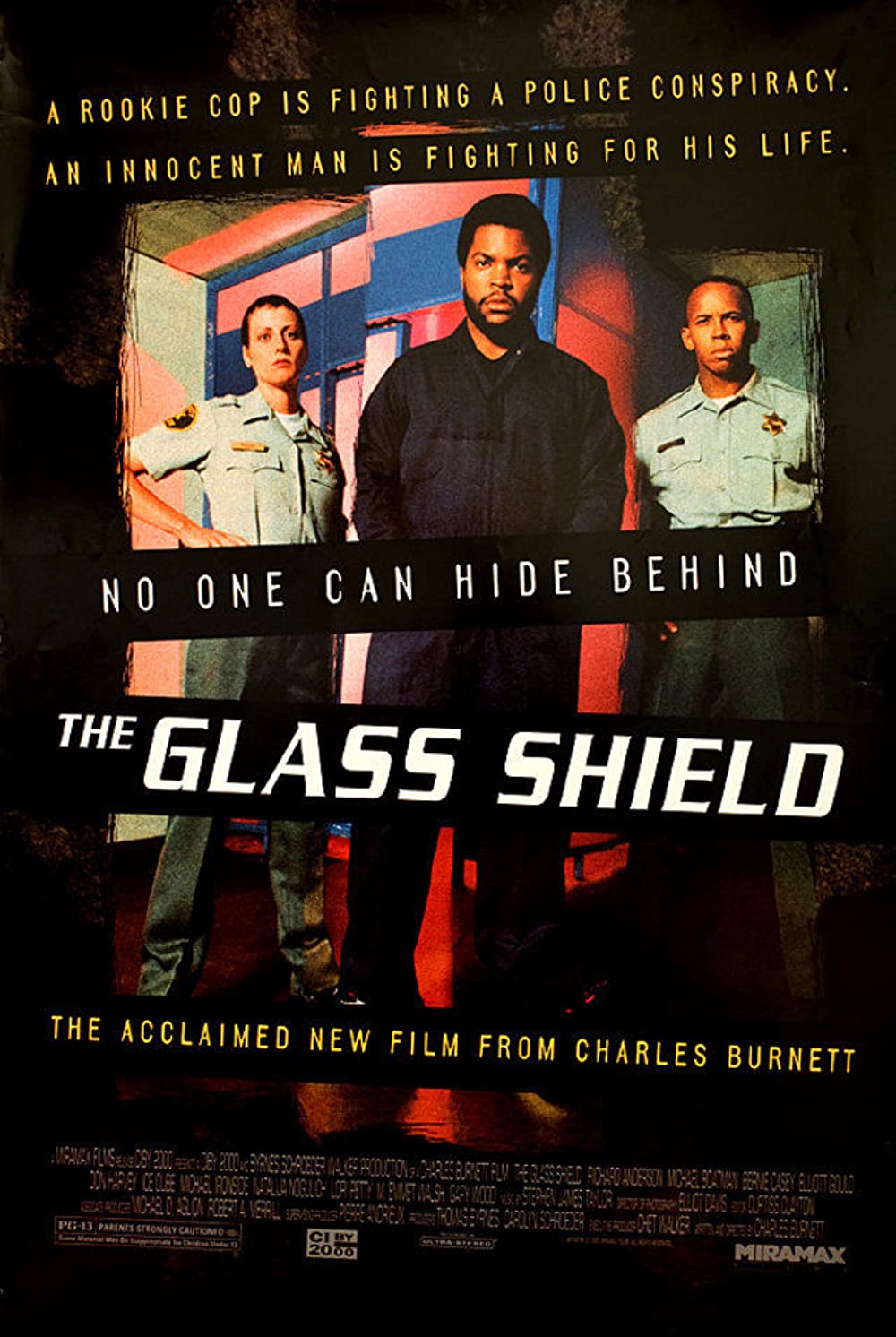

The Glass Shield (Prime Video)

Charles Burnett is among the great American directors of the last fifty years. The reputation of his first feature film, Killer of Sheep (1978), has only grown as it’s become more available to see (it tied for forty-third on Sight and Sound’s 2022 Greatest Films of All Time list). Another undisputed masterpiece is To Sleep with Anger, reissued by Criterion several years back. Burnett’s filmography is impressive (featuring a handful of stellar shorts and some unheralded TV work), considering that he didn’t get the shots he should’ve gotten after Killer of Sheep and his excellent follow-up in 1983, My Brother’s Wedding. There’s a seven-year gap between My Brother’s Wedding and To Sleep with Anger in 1990. No doubt that racism—a lack of opportunities for a promising Black director in the eighties—is the root cause of that silence. But then the nineties—with its burgeoning American indie scene—rolled around, and Burnett followed the well-regarded To Sleep with Anger with The Glass Shield. Released the same year as Crooklyn, it was my first Burnett film—I was initially drawn in by a crush on star Lori Petty. Despite the attention that his first three films have received in recent years, The Glass Shield remains undervalued. It hasn’t gotten a physical release, and this is—as far as I know—the first time it’s appeared on a streaming service other than MUBI (where it played for a month over six years ago). It’s only the second film where he worked under more typical Hollywood conditions. Michael Boatman plays J.J. Johnson, the first Black deputy in the L.A. Sheriff’s Department. He clashes with his white colleagues but eventually strikes up a friendship with Deborah Fields (Petty), the department’s first female deputy. Johnson backs up a white detective as he unjustly stops Teddy Woods (Ice Cube) at a gas station. Fields also bears witness to a racist incident. Eventually, Johnson and Fields begin to uncover the institutional racism and corruption that run rampant in the department. The Glass Shield plays like a precursor to David Simon’s The Wire and seems more relevant than ever. It’s an ambitious and complex moral drama that refuses easy answers and doesn’t offer any easy redemption. Burnett, like John Sayles, utilizes the political potential of genre cinema to great effect. He directs, as always, with gentle precision. He’s a complete filmmaker who has never betrayed his vision and has suffered in semi-exile for his refusal to bow to Hollywood’s expectations. Think too hard about all the mediocre filmmakers who got shot after shot after shot, and it’ll burn a hole in your head to imagine the opportunities Burnett hasn’t gotten. I’m beyond glad his work has been rediscovered and reevaluated in the last decade, but we should have so many more films from him (I’m especially angry that his adaptation of Chester Himes’s The Crazy Kill, retitled Man in a Basket, has never received financing).

William Boyle is the author of the novels Gravesend, The Lonely Witness, A Friend Is a Gift You Give Yourself, City of Margins, and Shoot the Moonlight Out, all available from Pegasus Crime. His novella Everything Is Broken was published in Southwest Review Volume 104, numbers 1–4. His website is williammichaelboyle.com.