Illuminated Manuscripts: An Interview with Fowzia Karimi

Interviews

By Merritt Tierce

Fowzia Karimi and I met in New York in 2011, as recipients of that year’s Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Awards. At the time, she lived in California and I lived in Texas, and, as is probably typical of people brought together for a brief ceremony of good fortune, we didn’t stay in touch. But five years later we recognized each other in the lobby of a black box theater, in the suburban college town where I lived; it turned out she had moved there, and I had the pleasure of getting to know her and her work. I could have spent hours in her studio, looking at her paintings and drawings and at every object. This room in her home is a nice cognate for Above Us the Milky Way, her first book, as both contain many beautiful and extraordinary creations, on a scale I would call not miniature but perfectly small. And yet each image created through story, or story through image, somehow displays the universe in its drop of water.

This is not a book that can be situated easily within contemporary literature, and not only because it is its own unique hybrid of word and image. It is the compressed and potent and intricate work of a storyteller from the past, or the future. A fabulist, a psychopomp, a mystic in the lineage of William Blake. Or as another brilliant painter-reader-mage put it, this book feels “like Gogol and Calvino had a daughter who was also their mother.”

To make something beautiful, you have to pay attention, which is also what you have to do to survive. You have to be waiting and seeking, ready with your talent and your heart, whenever luck arrives to save you. I didn’t ask the artist any questions about pandemic or war, but don’t be misled by this conversation’s focus on craft. Above Us the Milky Way is an essential text for our time, perhaps because it is not of it. It bears witness, and attests to the necessity of bearing witness. It understands that atrocities and reverberating sorrow must live within the same pages as a young child’s lost moments with a housecat, that all experiences both vanish and go on forever.

I didn’t notice until I began this interview that we have switched places, as I now live in California and she in Texas. There is perhaps no meaning to this coincidence, but it seems resonant. If there is anything worthwhile about tracing the intersections of cosmic paths, of observing how divergence and collision are the order of the universe, at once surreal and banal, Karimi is a master of this form: Some will come in, some will go out. Let the record be drawn and remain.

Merritt Tierce: When did you realize that what you were making would include both text and images, and what led you there? Was there a particular image that insisted on being accepted as part of this tale, and opened the door for others to be considered? Or was it an illuminated text from its beginning?

Fowzia Karimi: I spent a number of years working on this book and at points have tried to answer this question for myself. When I have, I find I go back further and further in time to find the source. Growing up, from elementary school all the way through college, I illustrated my essays and reports with drawings, photographs, or dioramas, leaving many teachers perplexed. I had a hard time separating language and image when expressing myself on the page. I didn’t realize I wanted to write until around the age of 30. Writing and reading were so close, such a basic part of my life, that I couldn’t see writing as a vocation. I was a voracious reader and I kept a journal for years; this is where my writing practice comes from. At times, I did drawings in the journal to clarify a point for myself when language couldn’t get at the thing. I also had a separate dream journal that I illustrated with dream images. Dreams have their own language, a highly visual and symbolic one, so this journal was image-heavy. Writing and books were too close, akin to breathing or eating, so that when I realized as a teenager that I wanted to be an artist, I went to the obvious, to the visual arts.

When writing Above Us the Milky Way, from the beginning the images rose up in my mind as I wrote. While I’ve always loved illustrated and illuminated books, and knew I wanted to use images in my own books, there was a part of me that really wanted to work with language alone. I felt a good deal of ambivalence and put the images aside at times. I wanted the text to do the work text does, using its own mechanisms, and to graphically sit on the page alone. I sometimes feel that there is nothing more beautiful than clean, black typeface on the page. But the images, having their own urgency and mechanisms/language, kept pushing in. And the photos, which are an important part of my memory, asked to be included as well. So I acquiesced.

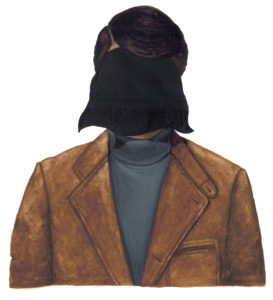

There are single images which do more work than dozens of pages of text might. I could have written a great deal more about my cousin who, being many years older and a husband and father, was like an uncle to me when I was little (the piece “taxicab driver” in the book is about him). He remains one of the most beautiful, happiest, brightest people I’ve ever known. He was one of those adults that children cherish and into whose arms they fly on seeing them. I spent many hours chasing or being chased by him, laughing with him, or perched on his shoulders as he carried on with things. He is at the very heart of the book; in fact, the book grew around him. And I can pinpoint his disappearance (and subsequent torture and murder) as the defining moment of my life, the moment that created a Before and an After. I could have written much more, but I chose to anoint him on the page through this painting, to give him a final resting place. He was one of millions of innocent people swallowed up by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, and the war that followed.

MT: Your author photo and some of the portraits in the book show the back of the subject’s head, inviting the realization that we almost always paint and draw and photograph and care about the front. What is the meaning of a face, or the meaning of withholding it? (Or what is it about the back of the head that interests you?)

FK: I didn’t initially set out to withhold the face in my paintings. But I realized after a while that the human faces in the illuminations in my book were either covered, transformed, or missing altogether.

In this painting of a group of female mourners, their faces are necessarily partially covered because they are in mourning; as Afghani women, they cover their heads when praying for the dead.

In the painting of the bridegroom who has been hacked to pieces by the government and returned to his bride in a box the night before his wedding, the groom has lost his humanity but, through ritual, is resurrected as a bird; his transformation is incomplete though, and he retains his human eyes and ears.

These were some of the earlier paintings I did, and I realized that on some level and for various reasons, I was making a choice to not show the human face. I took out a painting, with a face, I’d intended to include and, moving forward, decided that the others would follow the convention of the hidden/missing face; it turned out it made sense at every point onwards, for unique reasons.

There are multiple reasons why I chose to paint the above image of my cousin, the taxi driver, with his face covered. While I have a keen memory of who he was, I can’t remember at all what his face looked like. In the single image of him that I’ve held on to in my memory, I am chasing him as he walks up the stairs into his apartment; I can only see his back. He was picked up, imprisoned, tortured, and buried alive by the Soviets early in the war. All I knew at first, at the age of six, was that he had disappeared; we never saw him again. He was erased, and therefore faceless.

Many of the images in the book are inspired by paintings from both Eastern and Western illuminated manuscripts. (The painting of the mourning women, above, is based on illuminations of nuns in prayer.) There is a tradition of covering the faces of holy figures in early Central Asian and Turkish manuscripts. As a way to honor and sanctify my cousin, I chose to cover his face.

His brother, about whom I wrote the piece called “suit,” was beheaded by the religious police a few years later.

His head, transformed into a messenger, appears later in the book as war’s wail; carried in the mouth of a mythical bird, he delivers war’s pathos to any who will listen. The face, our most human aspect, in death becomes a mask. In the latter image, I chose to transform his face into an inert mask which, nonetheless, can still wail through a permanently open mouth.

MT: If it isn’t giving too much away, can you talk about how you selected the photographs you included, and how you decided where to place them within the text? Tell me the story of these photographs, as much as you care to reveal. Who was the photographer? Who kept the photographs? Who told you the stories behind these images?

FK: The images I painted for the book were ones that rose up in my mind as I wrote. Because image and text reveal different elements of a story, they allowed me to say something through paint that I could not or did not want to say through language. The photographs, taken mainly in Afghanistan and California, by various family members, are ones I’ve known intimately most of my life. When we emigrated, my parents packed the photos, knowing their value. In the beginning, they were a link to home, to our lives and our family in Afghanistan. As time went by, they gained more significance as bricks in a narrative of our history that we tried to construct. Especially for us girls, they captured events some of us were never in attendance for or were too young to remember. In some ways, the photos took on a dreamy quality representing a very distant place and time; in other ways they brought the earlier reality into sharp focus.

From the beginning, they were objects of value. My father loved technology and took photos of regular, everyday moments at a time when I believe most people in Afghanistan did not. So we had more to begin with, but my parents also had the forethought or the opportunity to bring their photographs with them when many immigrants did/could not; family photos were another casualty of the war. Some of our photographs were in a large album my mother had put together, but most were kept in a small, old suitcase, what I believe is called a train case, something my mother purchased at her thrift-store job. Either alone or in groups, my four sisters and I would click open this case and pull out the photos and laugh or reminisce over them. In one sense, they were very precious; in another, we treated them carelessly, rummaging through them, pulling out our favorites or ones we had questions about, tossing them on the floor where we sat, tossing them back into the box when we were done. And we added to the box over the years.

My mother was the fountainhead of our history. But my own memory is long and keen, to an extent that often has me viewing it as a curse as well as a blessing, as Maurice Sendak viewed his. I can remember the moments when some of the photos were taken, and other moments when I first saw some of the prints brought back from the photo lab. I remember also the images in reverse values, the negatives, which seemed to tell a different story. The photos taken before my birth were always more intriguing to me, and I could reliably go to my mother to ask her about the places or the people captured in them. I knew I wanted to include these photographs I love and know so well in Above Us. I collected/borrowed a group out of the box that held them all when I began to write the book, and as I wrote, some fell into place. Others I worked in later. Like the paintings, the photos rarely illustrate the text. But they are in conversation with it. Unlike the paintings, there were a limited number of photos to work with, so it usually was a matter of finding a fit after the writing was done.

This is a photo of my parents getting married. I paired it in the book with a piece about the brutal murder of my father’s best friend, who was killed the night before his wedding. The man himself appears in another photograph later in the book.

In this photograph, which accompanies “Mother, ill,” a piece about my mother’s tremendous grace and strength in the face of her many illnesses and surgeries, she sits beautifully dressed and made up two days after giving birth to her second daughter (who is being held in the lap of my paternal grandmother). My mother continued to show this strength and grace throughout her life, and in her final weeks in the hospital as a cancer spread from her leg through her lymphatic system and into her lungs.

MT: After so many years painting and drawing and writing, have you noticed that your ideas for paintings and drawings come to you in certain ways or at certain times or when you are engaged in certain specific activities? Or have you noticed they’re likely to be provoked by something in particular? (An example would be having ideas when one goes for a run or a walk or a drive or is about to fall asleep or feels angry, or in the early morning, or while doing the dishes. I’m intrigued by these associative rituals and experiences, and by the way that some can even become reliable generators—not simply the means by which an idea may come or be encountered, but the means by which it may be purposefully sought or conceived.) Do you notice any distinction between the ways ideas for your images come to you, and the ways ideas for your writing come to you?

FK: Images seem to always be present in my mind, or at least always waiting in the wings to make their appearance on the stage; they are very eager. Their expression is often through symbol, as if the mind is trying to get at the essence of something more directly, or more wholly, than language can. There are four activities during which they appear routinely:

When I think. Sometimes it feels as though language does not quite get at a thought, and an image will rise to express it, or the image vies with language in my mind to express a thing.

When I write. Because writing is a more focused form of thought, the images that rise up when I’m writing will also be more focused, more direct and to the point.

When I write. Because writing is a more focused form of thought, the images that rise up when I’m writing will also be more focused, more direct and to the point.

When I dream. Or when I wake from sleep, and especially as I am about to fall asleep. These images are so clear, so finished and refined, that they will often shock me into full consciousness. They are sometimes still images and sometimes moving, like short video clips. And often sound accompanies the imagery. Only recently did I finally look up this phenomenon: it is called hypnagogia, from the Greek hupnos (sleep) and agogos (leading). In my experience, the images in this presomnal state certainly lead to sleep, as they turn on the dream state while I am still conscious.

When I dream. Or when I wake from sleep, and especially as I am about to fall asleep. These images are so clear, so finished and refined, that they will often shock me into full consciousness. They are sometimes still images and sometimes moving, like short video clips. And often sound accompanies the imagery. Only recently did I finally look up this phenomenon: it is called hypnagogia, from the Greek hupnos (sleep) and agogos (leading). In my experience, the images in this presomnal state certainly lead to sleep, as they turn on the dream state while I am still conscious.

When I try to express myself verbally in conversation, an image will rise to do a better job than I am doing, and I find myself drawing it in the air with my hands. But I become self-conscious in the moment both because I am having trouble verbalizing my thoughts and because I am making non-sensical gestures with my hands.

Strangely, images rarely make an appearance in my mind when I do anything physical: exercise, wash dishes, garden, walk the dogs. I think I use these activities to shut the mind off.

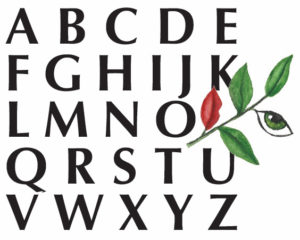

MT: Do you write by hand? Technically I suppose that typing in a word processor is also writing “by hand,” moving the wrists and the fingers, pressing the keys—it’s interesting that it seems writing must always be a physical act. Even if one is dictating, there is the physical production of sound. Even if one were using eye-gaze technology to train the pupil on the message letter by letter, there would be the motion of the eye, the action. The thoughts must always be brought forth, relocated by some physical mechanism, by some movement from inside the mind to outside the mind, from within the body to without. But I’m asking if you compose on paper with a pen or pencil, or how it goes. In my own writing, I suspect that what I would write by hand is different than what I would write on a computer, for any given idea. There’s a way that writing by hand is drawing—one is drawing the shapes of the letters on paper, a fact that your book calls attention to. And of course typography is about the letter as image. Thoughts?

FK: I love what you say about writing being inherently a physical act (though this may change any day now with new technologies that connect the brain to a computer). I think it is one of the most remarkable things about writing: through it we can express the most nuanced, the most abstract ideas, with a small set of symbols, using the most basic implements.

I stopped writing by hand many years ago, because painting and drawing, the things I still do by hand, paradoxically, damaged my body to a point where it became painful to write by hand, especially at a speed that keeps up with my thoughts. I worked for many years as a biological illustrator, and the small, highly-detailed paintings led to nerve damage, something I still deal with daily. It’s much less painful to type. And though drawing and painting still end in pain, if I space out the sessions, I can alternately work, then heal.

I absolutely agree that writing by hand will produce different work than writing on a computer. Words seem more precious on paper; the materiality involved—paper, ink or graphite, the hard surface beneath the paper—engages the mind in a distinct way. The actual mark-making, drawing, as you aptly say, makes it a more intimate act. And words are more determinedly permanent on paper. Depending on the implement used, one has to erase or cross out words, but their ghosts or chars remain; a path can be drawn back to the thought that produced them. On a computer, I can delete an entire page, or an entire chapter, and it is immediately gone, often along with original thoughts that produced the words.

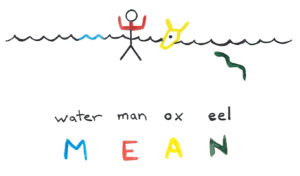

I think drawing and writing by hand are very much related. They share a common ancestor and were born out of our need to communicate through symbols, through images reduced to their essential character. The letters of the alphabet began as drawings, as distilled representations of things in our environment:

Painting, in my practice, is a step removed because of two things:

1) color, which is very evocative for me; it pulls me out of thought into the realm of emotion, and

2) the implement used; a paintbrush is more sensuous than a pen or a pencil as it travels across paper. I’m not sure if it’s because I paint in watercolor, but painting for me is akin to swimming, it engages the senses, quiets the mind. Conversely, when I write or draw, my mind is very present; it is doing most of the work.

MT: What skills, habits of mind, challenges, etc., translate from one practice to the other? For example, is there something you’ve learned from your practice as a visual artist that has found its way into your practice as a writer? Or something you avoid as a writer that has an analogue in your painting & drawing life?

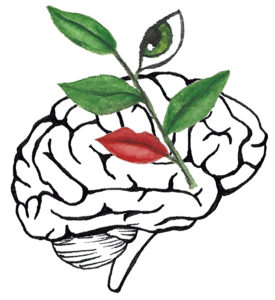

FK: I’m not sure that one practice directly affects or informs the other, but the two are in conversation. They each function through their own distinct mechanisms of expression, and it’s why I feel compelled to use both a visual and a textual language. The mechanism that functions in both practices is vision, which is directly wired to the imagination. I have a very strong visual sense, which was there before I ever picked up a pencil or brush, before I learned the alphabet. Vision, in both senses—sensory and imaginative—plays a key role in each of my practices.

When I write, I feel I am accessing the imagination through the mind. I see better when I close the eyes that are the sensory organs and look in. The outer world disappears and seeing happens in the imagination.

As a painter, I find inspiration mainly in the outer world—I am especially moved by color and by light, and more distantly by form. I have very engaged eyes that ceaselessly take in sensory information and need regular nourishment. And they are nourished mainly by beauty in nature, art, books. We seem to have a very low opinion of beauty in our culture today; it has become one of those dirty words in the arts, like “sentimental,” “precious,” and “craft.” I think there is a place for all of these things, and very necessarily for craft, in art. Personally, I value beauty above just about anything else. It is nourishment for the eyes, heart, and ultimately the imagination. My aim in my work isn’t strictly towards beauty; I also want to tell stories and communicate ideas, however ugly they may be.

And then there is drawing, which I distinguish from painting. I am not a very practiced or confident drawer, though I’m working to be freer with it. But it is necessary as a practical step, a link, between writing and painting. It is the “illustration” part of my work, whereas painting is its illumination. The drawing is the skeleton that gives structure to the painting, and conducts the conversation between the mindly writing and the more sensual painting.

MT: What is it about the pairing of image and text? I have found that perhaps my favorite form is that of the graphic novel, or even a single cartoon or a single image + caption, because it offers this magical combination. While your book provides a more oblique experience of text and image—there isn’t always an obvious or direct relationship between an image and the text surrounding it—what do you think is so pleasurable or compelling about this relationship?

FK: Magical indeed! I also love the combination of text and image. And love it in all its iterations: the sweet, innocent drawings in 60s-era children’s books where flat planes of color sit next to large blocky letters; the bold illustrations of comics and graphic novels, where text is the interloper in the image; the truly wonderful fairy tale illustrations of Arthur Rackham and Kay Nielsen, which bring as much magic to the tales as the text does; George Cruikshank’s comical drawings for the books of his friend Charles Dickens (two caricaturists working in concert); the mystical and often mischievous illuminations in Medieval manuscripts; Joris Hoefnagel’s exquisite natural history paintings paired with Georg Bocskay’s incredible calligraphy . . . The list is endless . . .

When image and text combine on the page, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. A synergistic, almost chemical, reaction takes place. Each element, text and image, speaks to the reader/viewer. But just as importantly, the two elements speak to each other. And it is this conversation between text and image that carries the potency and gives the pleasure you mention. While I love direct illustration, for me, the most mystical and powerful combination is found in illuminated manuscripts, works created entirely by hand. The images in these seem to rise out of the unconscious and hold a deeper symbolic meaning. Often the images in the manuscripts, whether scientific or religious in nature, and especially the drolleries and grotesques in the margins, seem to do their own thing entirely. Yet, they always speak back to the text and, in doing so, create a vibration on the page and a vibration in the mind as the reader’s eyes flit back and forth from text to image.

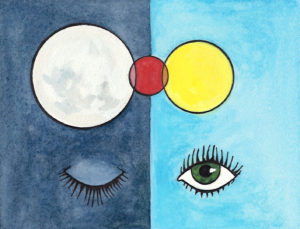

First picture: The eye according to Hunain ibn Ishaq, Chesm Manuscript, 1200

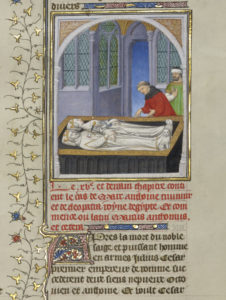

Second picture: Tomb of Marc Antony & Cleopatra from Giovanni Boccaccio’s Des cas de nobles hommes et femmes, 1409

MT: We’ve talked about how with writing we both experience a more available and direct path of expression, as opposed to speech. That the transmission is more fluid and there is a fluency to producing thoughts in writing that is absent with speech, as if speech and writing are controlled by entirely different areas of the brain (in fact there is some research to indicate this is the case). What about painting and drawing? Can you use words to describe what it feels like to paint—what it feels like in your mind? What happens? It’s almost easier for me to imagine what happens when a painter paints than it is for me to try to understand what happens when I’m thinking about how to say something in writing. When I write, the unarticulated reality of the something is present before, or whether or not, I am able to express it clearly. Is it like that with painting, that you see a vague or dim version of the image and then you try to capture it, to make it more clear? Or do you see the image very clearly in your mind, and it’s more about your technical ability to represent what you’re visualizing? Or what is it like?

FK: You are the only other person I know who experiences the paths of expression for speech and for writing as two distinct ones! I feel that the path of speech for me is an obstacle course, with all sorts of barriers that flip up to impede the flow of words from my mind to my lips. Speech feels clunky. I’m very right-handed, and when I speak, I feel like I’m communicating with my left hand, the awkward and dull hand. It is rare that I feel I communicate my thoughts well through conversation.

It seems that so much comes down to wiring. We’re each wired uniquely based on our genes, on our developmental term in the womb, the nutrition we receive or don’t, on how we develop once born, those first crucial years, the love we receive or don’t, and the accidents or traumas our bodies, our brains especially, absorb during our lifetimes. Up until my late 20s, I had a form of synesthesia that involved seeing a distinct color for each number and for each letter of the alphabet. And the colors, and through them those symbols, each had personalities. I continue to see personalities in shapes and colors, in everyday objects in my environment. Synesthesia is one of those conditions you learn to hide after a while, and fairly early on, once you realize people don’t share it. The color-symbol synesthesia mostly faded, perhaps because it isn’t generally recognized and reinforced by society, or perhaps my brain wiring changed.

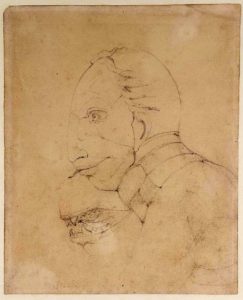

I consider myself a writer first, and more distantly a visual artist. We’re all taught to read and write early and this gets wired into us, but not everyone paints or draws. Those of us who do, pick it up later. Writing is the easier, the more direct form for me. I have a thought and can quickly and directly set it down in words. Language and thought are very closely aligned. But in order to paint an image I see in my mind, I have to go through many steps in the mind and in the world. I will have a very detailed, complete, and vivid image in my mind, but I don’t have the facility with drawing, or even with paint, to set it down as I see it. And the image in the mind is often just a flash—it doesn’t remain for long. William Blake apparently had visions, something like holographic images, that occupied the physical space in front of him; he could spend several minutes drawing from these visions, as others draw from life, following their every line and contour.

The Head of the Ghost of a Flea, William Blake, 1819

When I draw, I feel many of the same obstacles that I do when I try to verbalize a thought. While painting comes easily, drawing can feel burdensome and unnatural. By the time I’ve gotten an image on paper, it has traveled through kinks and coils and rarely looks as I first saw it in my mind. It is a translation of the original. It may be wiring, it may be lack of training or practice. It may be that I have so much affection for color, I move too eagerly to the painting stage. By the time I am there, I’ve already worked out all the kinks in the drawing and can fluidly paint.

Painting is sensuous, mindless. When I paint, the mind that functions through language recedes and a softer state comes to the forefront, led by an appreciation and love for color, and by attention to value and to form. The practice of painting for me is not dissimilar to being a passenger in a car or a train, moving through a natural landscape, taking in the forms and colors that pass by, feeling a sense of weightlessness, timelessness, and thoughtlessness.

Merritt Tierce is the author of the novel Love Me Back, winner of the Texas Institute of Letters’ debut fiction prize. Tierce is a recipient of a 2019 Whiting Foundation award, and was a National Book Foundation “5 Under 35” author. She wrote for the last two seasons of the Netflix show Orange is the New Black, and is currently working on various film and television projects. Her first published writing appeared in a 2007 issue of Southwest Review. She lives in Los Angeles.

Fowzia Karimi is a writer and an illustrator. Her work explores the correspondence on the page between the written and the visual arts. Her illuminated debut novel Above Us the Milky Way was released in April 2020. She is a recipient of The Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, and has illustrated The Brick House by Micheline Aharonian Marcom and Vagrants & Uncommon Visitors by A. Kendra Greene. She lives in Texas.

More Interviews