Kaleidoscopic (Re)Presentations: A Conversation with Mónica Ramón Ríos

Interviews

By Robin Myers

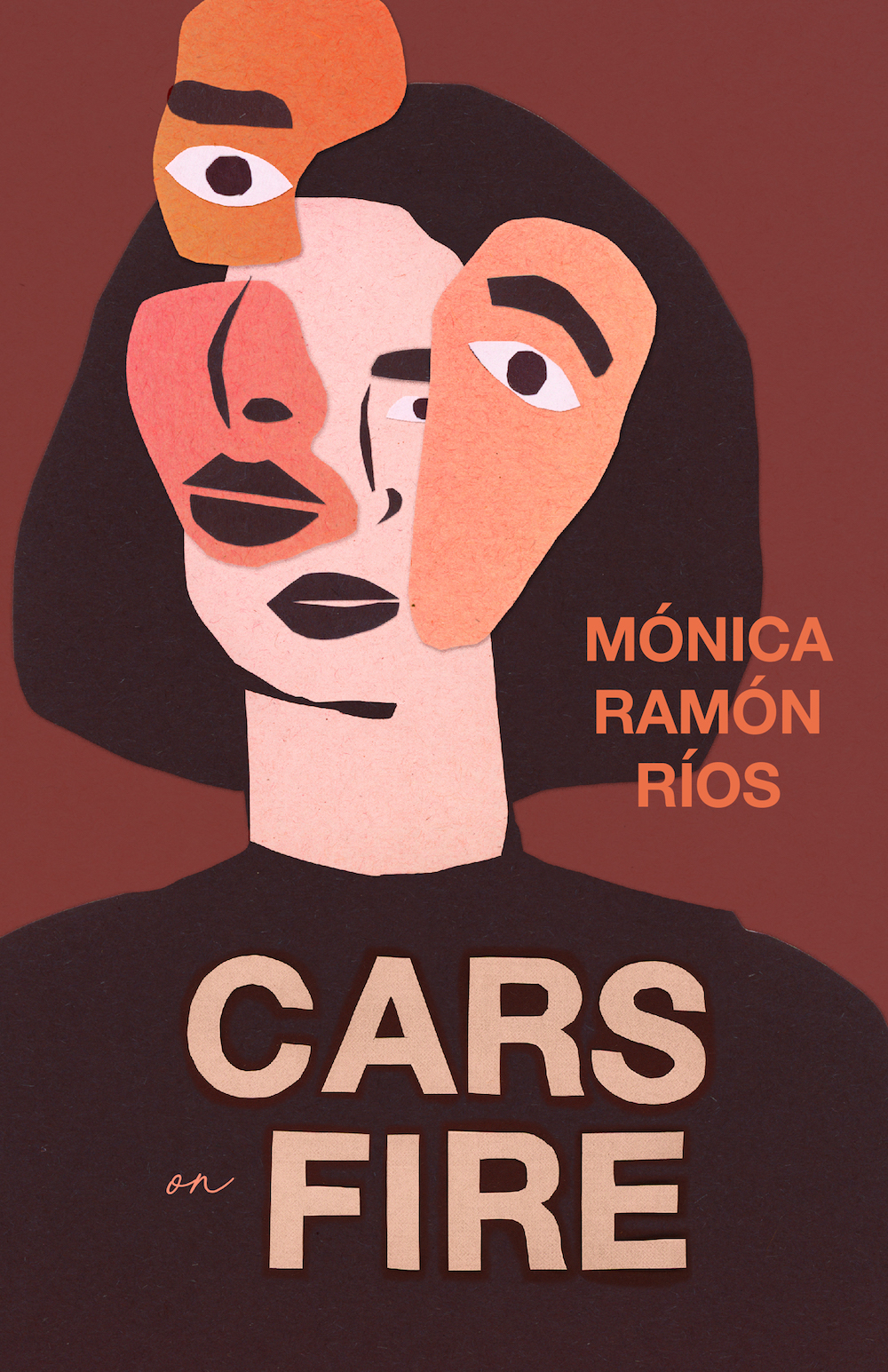

Cars on Fire is a short-story collection by Mónica Ramón Ríos, just published by Open Letter Books in my translation. And it’s a book of shifting shapes. The fifteen stories—divided into three parts, “Obituary,” “Invocation,” and “Scenes from the Spectral Zone”—transpire largely between New York City and Chile. They travel from a psychoanalyst’s office to an upscale mall in downtown Santiago to an art museum to a swamp to the Spanish department at a US university. Some have a realist bent; others are downright surreal. Their narrators—mostly women, mostly immigrants—include a writer, a patient, a professor, a student, an actress, a multitudinous “we” that expands into a mythological scope. They depict the hypocrisy of the academy, defend the right to rage in response to violence and injustice, and celebrate the transformative forces of art and desire.

ROBIN MYERS: I could go on! But I’d like to ask you instead: how did the collection come to be structured for you? And in what ways did you feel, as you wrote the stories, that they were speaking to each other? As I translated, I sometimes imagined them as a kind of song series: one completely different musical experience after another, jarring and thrilling in their contrasts, their color-scapes. But sometimes I thought of them more as a chorus: all speaking up at the same time, all claiming their place in a kind of riotous multiplicity. I’d love to have you discuss the relationships among the stories as they revealed themselves to you.

MÓNICA RAMÓN RÍOS: I like all the ways you describe Cars on Fire, Robin. I remember in 2010, when I came to the US, I was telling a colleague about my then-unpublished previous novel, Alias el Rucio. I told them I wanted to write a text where the identity of the protagonist was the central question, a protest against identity itself. I was dreaming of a character that mutated from male to female to animal to plant to thing to elements and pieces of all these without ever destroying the sense of narrative unity. Alias ended up being something different (I worked mainly with the idea of bodies being sewn back to themselves in scientific and medical experiments). Not long before I sent you the final version of Cars on Fire in Spanish, I realized that I had finally done something like that in the story “Invocation.” As you know, this story includes many transformations—or at least highlights the inability of language to name certain existences. There, identity and its languages belong to a future that has not yet arrived, and thus must be invoked. Identity can be created with very few, even marginal, elements. In other words, what makes us “us” is very fragile; it needs to be taken care of, nurtured, and treated with compassion, but it can also become a prison.

The urge to write these stories emerged, among other things, from a localized, experiential, desire-based knowledge/belief that the self is a perilous fiction that has been imposed on us both by very good literature and by very poor books. And I say this not because I read all the poststructuralists (which I did) or the postmodernists (which I ditched), but because I rebel against the idea of fixity, of borders, walls, names, or any supplementary tools to define being, voice, or even our work as anything more than fiction. I learned to write at a time when Chile was plagued by very bad neoliberal realism, which coincided with the most treacherous moments of Chilean politics: when the left sold the country and settled with the dictatorial right to create a new transactional structure of power—this is the order we are trying so hard to remove right now in Chile. In terms of literature, the transparency and immediacy of neoliberal realism was not only trying to oppose the literature of the ’80s (a dense oppositional, feminist, queering, literature of protest against univocal dictatorial violence, but also of military stupidity, embodied by the Ministry of Censorship). At the same time, in fact, neoliberal realism was trying to hide those power transactions. And it meant wanting to write like the gringo literature exported to Chile because the whole country wanted to enjoy their fucking McDonald’s. What came out of that was not literature, but a new writer who was a vendor, a new literature that was a product. It wasn’t even entertaining, because it made you lethargic, like the joints mixed with glue we’d buy on the cheap as teenagers to pass days that felt eternal and useless. This was a literature without consequences. But even back then, we still craved those moments of intense understanding that made us become trabajadores de la letra, writer-workers.

So, yes, the voice of Cars on Fire is a riot. I wrote all of the short stories, except one, after moving to the United States. And in many ways their voice also riots against the inherent racism in this country, especially the one concealed behind niceness. I aim my pen at those people who abuse us saying they are helping us, saying they are our friends. My riotous eye sees right through them, and I can’t help but call them out; this is evident in some stories of the section “Obituary.” But my pen is also a gun that wants to blow up the monovocal, monotonous realities imposed on us by capitalism. I don’t think it’s worth living a life like that; all the depressed CEOs should just kill themselves or move to England. The rest of the world should be intensely ours. All the love stories in Cars on Fire are fired up by the feeling of intensity embodied in the most unexpected ways. My stories are a way for me to seize them—besides the fact that writing is, for me, a very pleasurable experience. In that intensity, we are able to express the many aspects that sometimes coincide with our own selves. This voice wants to express them all. I like to call it kaleidoscopic.

RM: Could you talk some about the role of protest in Cars on Fire? And maybe also about what it feels like to revisit the book now, in a time of such turbulence and uncertainty in both Chile and the United States, the two countries where the book—not to mention your day-to-day life—is rooted?

MRR: When I read your question, I think about “Dead Men Don’t Rape,” a short story I wrote for a reading of Latinxs against Trump in October 2016. There, I imagined all the shitty ways he would destroy, banish, dehumanize, and kill people like me. But in the story of the migrant who ends up writing speeches for the man with hands like a squirrel, I also channeled my frustration against my landlord at the time, who was harassing me out of my apartment, and my boss at the time, who extracted my knowledge in several humiliating ways while also looking at me with desire. No matter where these men came from, all of them, at some point or another, made a reference to my visa status. This was the perfect excuse to exert their sense of ownership over what was theirs: money, territory, knowledge, body, language. These three situations were part of a similar problem, which is called imperialism, which is called patriarchy, which is called extractive capitalism.

Also, “Dead Men Don’t Rape” pays homage to the feminist movement against femicides, mainly in Mexico and Argentina. Later, it became the MeToo movement in the US and the Mayo Feminista in Chile. Today, I see that feminism is the guiding force for the protest movements in Chile. I experience this moment as a big finally, when many are eager to see those corrupt places of power finally destroyed. As the short story goes: I want to use my words as bullets.

I am currently in Chile as I answer these questions. There’s a regional quarantine in place and I can’t leave the house where I’m staying. I came here for a couple of months to work on the last details for a book on Chilean female filmmakers of the 1910s and 1920s who few people know about. Lately, though, many things that have been hidden have been rising to the surface, and in those findings, we have uncovered a potential new community; we are experiencing it, it is present, but it’s not entirely here yet. Under this quarantine, at certain times of day, it seems to slip through our fingers. I left Chile ten years ago and the feeling I had when I came back in February is one of potentiality. It’s as if we finally have a common ground where we can talk without fear—a common ground on the ground, not what’s reported in the news.

Literature (with a capital L) is struggling to find its place in this; many writers feel lost. Literature has revealed itself as a conservative institution, unable to understand that the street is the place where art is being legitimated. A few older feminist and revolutionary voices have reemerged, but there are still so many women struggling to make their literature—their amazing literature—heard. Everyone who writes bullets, not Literature, knows that while philosophy and journalism are struggling to describe the present, literature needs to forge a language for the future. I am not saying that literature allows us to say what is unsayable—I am not a Romantic! I see a gap between what is happening—reality or fantasy—and a way of expressing it. That gap is literature. It’s not about finding the perfect words to express what’s happening to us, but to encode it; that is, to displace it, and to make it un-autonomous. In other words, to highlight the continuity between the literary and, for lack of a better word in English, our envolventes.

RM: It seems to me that two of the central forces at work in the book are, on the one hand, the human thirst for revenge (explored especially in part one, “Obituary”), and, on the other, the exhilarating multiplicity of love and desire (which particularly characterizes part two, “Invocation”). Part of what fascinates me about the book is how your ventures into the intentionally exaggerated or even the fantastical—I’m thinking of the comical distortedness of the academic administrator in “The Head,” the amorphous creature in “Extermination,” or the sinuous human-animal metamorphoses in “Invocation”—affects the dynamic between your characters and their environments, or with each other. Or would you object to my use of the word “fantastical” here? Maybe what I’m really asking is how you see, and like to channel, the slipperiness of place, time, and form in your work.

MRR: I would rephrase it as Mónica Ramón’s thirst for revenge and their desire for the exhilarating multiplicity of love. I see the stories you’ve mentioned as pure realism. I say this with a mischievous intent to contend the possibilities of the real and to subvert the straitjacket that has constricted our experiences.

I am uncertain about the word “fantastical” because lately it’s been used to describe a literature that is different from what I do. That other literature works more with the uncanny: strangeness comes to destroy our sense of normality, which is usually embodied in the family or in a very tight, small, restricted society. My short stories start where normality is already difficult to locate. In “Extermination,” for example, the child who narrates lives in extreme poverty, his playground overflowing with the same filth from which the body of the Extermination emerges. Amid a disaster that destroys a group already afflicted by numerous forms of violence, what emerges from filth is friendship. The disaster is accompanied by the interferences of local authorities and transnational corporations that eliminate the narrator’s and the Extermination’s home-bodies. The story’s emphasis is not on a rigid normality that shapes a flat commonality, but on an existence that has already been complicated by the very fact of lacking what is “normal.”

There are several writers who appear in the book, cited, interpellated, or manifested in spirit: Marosa di Giorgio’s stories; Diamela Eltit’s novels; Cristina Rivera Garza’s elliptical plots; Gabriela Mistral’s ghostly novel-poem; philosophy and theory addressing the inconsistency of reality or analyzing the conditions for a new reality, such as Rosa Luxembourg or Alexandra Kollontai; and a great deal of queer, feminist, and political theory. A few things from those books that stuck with me (and which makes me depart from trends of the fantastical): for one thing, even if they refer to a town, city, or place by name, the spaces are difficult to localize. This delocalization already figures the stories outside the scope of an imposed form. In the texts I’ve drawn from, the family, for example, which is a persistent theme of the recent fantastical literatures, is always displaced and re-signified as something more than a mere site of law and trauma. Characters and their sociability are questions, inquiries into the very premises of those bonds. Each fiction must invent its own language or structures to redefine them—characters and their bonds—in terms beyond what we usually suffer in our everyday sociability. The literature I am interested in is rooted in representation not as an answer, but as a potentiality. Representation loses its prefix and becomes presentation, thus rehearsing other ways to communicate with the readers. Put another way, it is a kind of writing that works from the ground up to emerge, eventually, maybe, or maybe not, as literature.

RM: I love the idea of representation becoming presentation. And I love the way that the delocalization you describe—the open-endedness of place, character, and their limits—serves as a way not to disorient the reader, but to invite them into radically new kinds of engagement. You live most of the time in New York City, a place that has been relentlessly represented (prefix intact!) in literature, and multiple stories in Cars on Fire are set there. Could you talk a bit—and maybe we can end here—about the role of New York in your book, about the premises you question and the potentialities you explore there?

MRR: Maybe I should start by saying more about the representation/presentation divide— skipping over the theoretical universe contained in the prefix. I encountered these ideas as I was thinking about cinema. I’m also a cinema scholar and critic, and I like writing about films directed by women, usually women I respect both for what they do onscreen and for their practices beyond it. Ever since I was a studious and perversion-loving teenager, I knew there was something fishy about the idea that, if you were going to be a good student of literature and a well-behaved reader, you should eschew whatever happened outside the frame (whether screen or book), thus allowing us to revere male writers who were fascists, abusers, rapists, and/or bad writers. The fact that the female body, the very fact of having a female body while writing, was always in the forefront of women’s works as a lack demolishes that hygienic fantasy: whenever a woman signed a text, there was always something missing, something wanting, always insufficient, even if you held a cigarette between your hands, wore spike heels, or used any other kind of prosthetic phallus. In other words, being a female-bodied writer was already revealing that that the separation between the inside and outside of an aesthetic frame was not, in fact, a separation at all. This didn’t mean, as the professors at my first conservative alma mater insisted, that you should never focus on the writer’s biography. It meant that there was no real difference between living a life and creating a work. In other words, you cannot be a feminist, a radical, a revolutionary only in in writing; these things should also be reflected in your practice. And the first practice should be to trace the continuities between the book and the world.

In the current crisis, many smart people have been writing illuminating texts about the “modes of production” of literature. But what’s especially interesting to me at the moment is what literature can do, because literature can also be conceived as an action. Thus, my use of potentia, a force, a becoming, of the abstract into materiality. By seeing literature in this light, I might not only represent, but also create a space for that fiction.[1] To represent accentuates the laws by which something becomes aesthetic. It can be learned, manipulated, and used to create forms through which identity, among other things, can be exploited. If we dissolve representation into presentation, we might find a place where we can stretch what the aesthetic is: where the very existence of a body coincides with the way it is represented. Let’s think about a body who, when naked, is not what it really is, so it dresses up in particular ways to become its true self. Then, the presence of a describing pen or an observing camera is not excessive: in fact, it is the very place in which the person/character is presented/represented. There is no longer any difference between those two ontological situations. As a dear poet friend told me once: “For you, everything has to be aesthetic.” The “everything” was life itself, and she was right.

Am I avoiding writing about New York? A bit. I really liked the New York I wrote in Cars on Fire, but after so many catastrophes, I feel it is no longer there. I haven’t been living in the city that long, only ten years now, six years when I wrote the book. So the experience depicted there is that of an outsider, a recién llegada. This perspective is evident in the title story, “Cars on Fire”: the experience of living as a foreigner in what already feels like home, but isn’t, because it’s continually taken away from you by any act of mistranslation. This is why I chose to refract the image of la-escritora-with-an-accent through the eyes of a man who, I don’t know how, kind of by surprise, became the nameless narrator with a father problem.

I have two friends who recently shot films in New York. One frames his characters biking around the lake in Central Park and taking planes out of the city. The other places them in locations that feel grounded in a city we all know well, whatever name it has, wherever it may be. The latter creates a sense of home; the former, a story in which leaving is the only act that makes sense, because home is somewhere else. One of the things I wanted to avoid was the postcard effect of New York. In writing the stories “Cars on Fire” and “The Animal Mosaic”—both of which make direct references to Crown Heights, where I was living at the time—I wanted to portray the experience of a life rooted in a place that escapes its characters altogether. Home, then, is merely ciphered in the words the characters write and share: a sort of secret language that can only be defined by migration. Maybe then I could express how important literature is for this migrant writer. It’s home.

[1] As an addendum, let me just note the irony of writing about action while under lockdown. At the same time, never before has fiction been so pertinent: its action is lifesaving for non-physical bodies.

Mónica Ramón Ríos is a writer, editor, and scholar originally from Chile. Her books of fiction are Cars on Fire (2020), Alias el Rucio (2015/2014), and Segundos (2010). In 2008 Ríos co-created Sangría Editora, which publishes fiction, essays, scripts, plays, and agitprop.

Robin Myers is a Mexico City–based poet and translator. Other recent or forthcoming translations include include The Restless Dead by Cristina Rivera Garza (Vanderbilt University Press, fall 2020), Animals at the End of the World by Gloria Susana Esquivel (University of Texas Press), and Lyric Poetry Is Dead by Ezequiel Zaidenwerg (Cardboard House Press).

More Interviews