Keeping Time at Texas Roadhouse | A Conversation with David Nutt

Interviews

By Gina Nutt

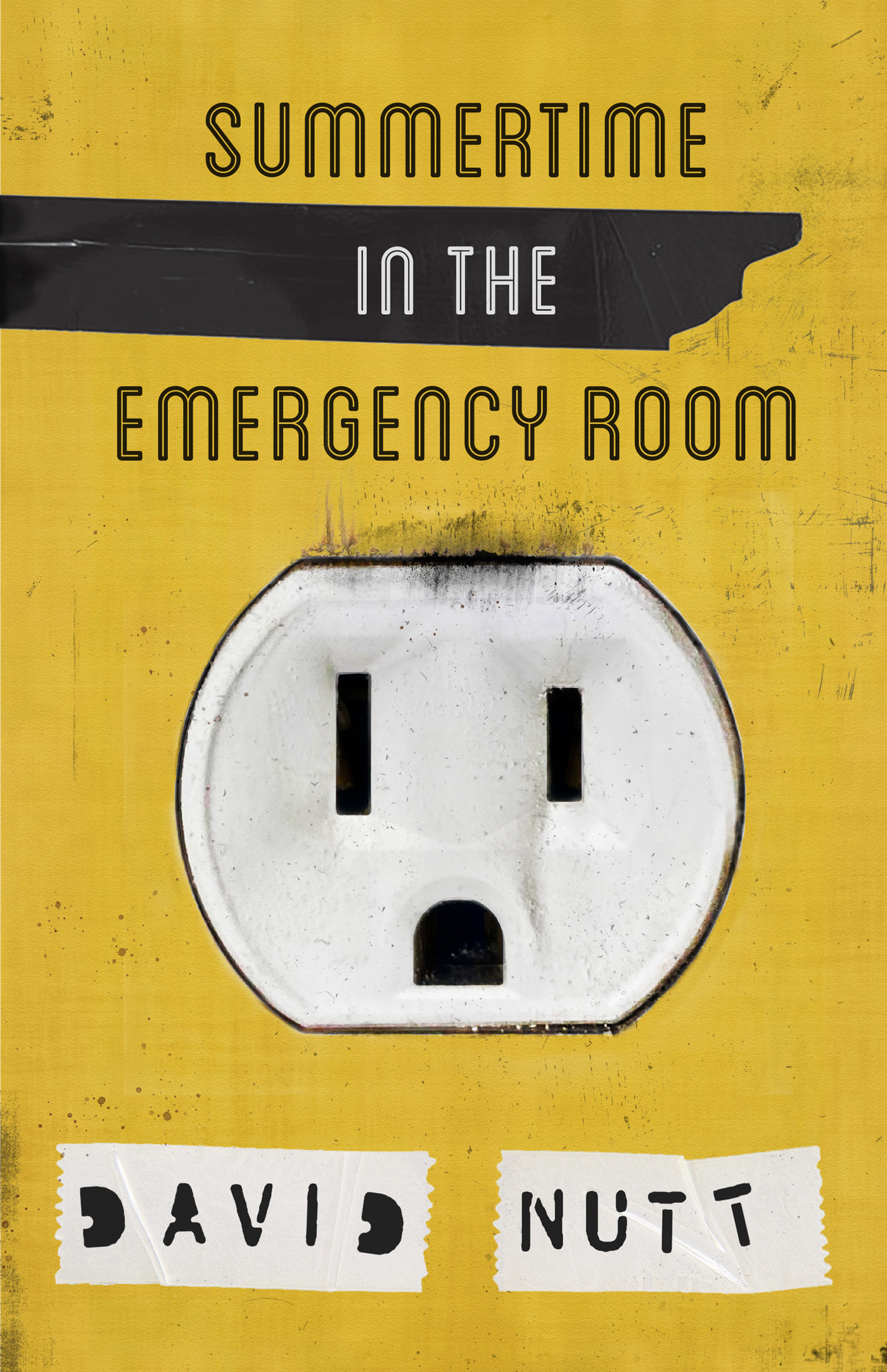

“I think we’ve got to nut up or shut up,” he says when I ask whether he wants to get takeout or eat at the restaurant. In grad school, where we first met, we blew our stipends on cactus blossoms and beers at the Texas Roadhouse in Syracuse, New York. Something about the place—raw steaks in the display case near the entrance, oil saturating the air, cracked peanut shells on the floor—brewed agitation. Usually, by the time we got to paying the bill, an ornery pall had settled over us. We haven’t been to one since. Following the release of David Nutt’s second book and debut story collection, Summertime in the Emergency Room (Calamari Archive), I wanted us to revisit the place that conjures a time when these stories, or their early predecessors, originated.

Among my favorite elements of Summertime are the characters: wide-hearted slackers, addicted lovers, an unmoored man in an astronaut costume who befriends a lone coyote. These are people electrified by longing, loss, and misses (often of their own making). They feel their way through the blitzed wreckage of their lives, attuned to the crackle of language and connection. Each story has an undertow that pulls us from our comfortable nooks and carries us elsewhere: unfamiliar neighborhoods, head spaces, griefs, afflictions, and loves. In honor of the collection’s upcoming first anniversary, David agreed to indulge my prying alongside beers and fried vittles as we dug into the stylish, sharp, human journey he’s sending us on in Summertime in the Emergency Room.

Gina Nutt: So, what looks good? I mean, you’ve gotta do a cactus blossom.

David Nutt: The cactus blossom, the rattlesnake bites. Those are what you wanted, right?

GN: Yeah, I mean, the fried pickles, too.

DN: You want to do all starters.

GN: Kind of, yeah.

DN: They’ve got cocktails.

GN: Oh no.

[Unfolding napkins that contain giant steak knives]

GN: It’s quite an operation.

DN: You could skin bison with this.

GN: Where are the peanut shells? So I guess on this momentous occasion of your second book being published, we’ve come to the place where we used to fight. Great.

DN: We had all our best fights at Texas Roadhouse.

GN: The characters in Summertime experience loss, mishaps, maimings, and emotional malaises. Everyone is unsettled in some way. Or they plunge deeper into unease over the course of their story. What’s at the forefront of your mind when you’re spending time on uncomfortable emotional plateaus with characters who can’t get their shit together?

DN: Is this your way of asking, “Why is my husband so sad?”

GN: I don’t know, man. Answer the question you wish you were asked.

DN: What jagoff gave you that advice?

GN: I married him.

DN: Maybe I’m a sadist who likes to put my characters through the wringer. That’s the cheap answer. Really, though, that’s where you find the best drama. You back your characters into a corner, then another corner, then another. That’s what reveals their nature. The character of the characters, their weird angles and rough patches. How do they respond? My characters generally tend to fuck up and fall apart because they’re awfully flaky and unsure of themselves. Those are the kinds of humans who interest me. Who wants to read a success story? Sociopaths, that’s who.

GN: A redemption story.

DN: I feel like stories in which characters disintegrate, sabotage themselves, and make a muck of things—those can be redemption stories, in a way, if the people at least manage to crawl across the finish line. Even if they’re dead last, they’re still finishing the race. So I don’t necessarily even see them as being sad. Redemption in fiction is overrated, anyway. At the very least, it’s redundant. As I heard Sam Lipsyte say in a workshop twenty years ago: “The fact that the writer wrote the story, rather than blowing his brains out, is all the redemption you need.” A story’s very existence is life-affirming. The creative act.

GN: Do you remember Pig-Pen from Peanuts?

DN: He was my favorite.

GN: He has this aura of dirt around him. He joyfully exists in his filth, and all the other characters still hang out with him. Many of your characters have a similar smoggy patina around them, and most of them are making their dirt clouds bigger. So, how do you entice an audience to spend time with these people?

DN: A lot of it comes down to humor. The comedy, the yucks, the slapstick. It serves two functions. It’s a release valve for when things get too uncomfortable. You crack a joke when you’re nervous or you’re tense, and that kind of gallows humor relieves some pressure. But it also allows you to go further and get even darker. It’s almost a way of distracting the reader. You’re not pausing long enough to consider how bleak things are until it’s too late. A good example is in “Theories for the Eternal Dog.” Renfeld, the drug dealer’s lackey, has come to harass the narrator and ends up moving into the narrator’s parents’ house. In the middle of the night, the narrator wakes up and finds that Renfeld is cutting the calluses off the bottoms of his own feet and saving them in a plastic baggie because he sells them as sea monkeys to kids. Maybe it gets a laugh because it’s absurd. You’re probably not thinking about the fact that this guy Renfeld is a recovering addict who’s as unstable as the narrator and that he’s mutilating himself because he’s broke. He’s just as desperate as everyone else. So maybe you laugh at the dumb gag, but there’s this lingering aftertaste of desperation about the guy. Then you find out in a later story that things did not go well for him. The sea monkeys will not save you.

GN: Well, I do feel like humor is the heartbeat of this book. Some of the funniest things are the saddest. The humor urges you deeper in places where melancholy underlies the jokes. I’m also enchanted by your sentences, which are very stylish. I know you extensively revise (I can hear you in the other room), and I’m wondering how much of the sentence work comes later and how much you get on the first whack.

DN: I mean, I always want to get it right on the first try, even if that rarely happens, because you save yourself work later on. There’s nothing worse than a story that feels half-assed and rickety. It leaves you thinking, “Well, how do I salvage this?” You might patch it up, slap on some band-aids, but it will never have the integrity or vitality of something created out of a pure, generative voice—if that makes sense. And I always seek a stylized prose. My favorite writers are all loud stylists. Whether it’s Stanley Elkin or Lorrie Moore or Garielle Lutz. James Robison. Or Beckett. Melville. Any writer who is worth his or her salt is a stylist. Who’s a good writer who doesn’t have a distinctive style? There’s no such thing. It might be a quiet style, it might be subdued. But style is just the way you inflict your personality on storytelling, on narrative.

GN: You’re inflicting your malady on the book.

Waitress: How are the appetizers?

GN: They’re fantastic.

Waitress: Do you want to order more?

DN: I think we’re good with these, thanks. But, for me, an interesting sentence? That’s only the starting point. That’s the baseline. It’s not the end game. The end game is to write an engaging story with emotional stakes and some kind of—

[Screaming in the background]

GN: It’s someone’s birthday.

DN: Oh, good.

GN: They’re gonna ride a bull.

DN: They’re gonna get in a fight tonight.

[A loud yee-haw]

GN: Yee-haw! You get nice synergy between style and emotional heft. That balance seems important.

Waitress: Would you guys like more bread?

DN: Can we please get water? Sometimes style for style’s sake offers its own pleasures. I just like plot and narrative and all that stuff, too. Really, I want art that does it all. Barry Hannah had that thing he told his writing students: “Thrill me.” Those thrills can come in a variety of ways. I think what you’re really looking for is something that has an energy and momentum and surprise. Maybe some challenges, too. People talk about challenging fiction like, “Oh, this is work, it’s like eating your vegetables.” Well, I like vegetables. It doesn’t feel like work to me.

GN: I like to think of it more as the thing we get to do. Like, if no part of it is joyful or meaningful, there are other ways to spend our lives. Can you tell the people about your process?

DN: The people don’t need to know my process. The people don’t care. It’s very bland, you know. I’ve got a nine-to-five job. I wake up and try to get to my desk by 7 am and write for an hour, maybe two hours, before work. And I do it every day. If it’s the weekend, I’ll write longer. But I’m usually shot after three hours anyway.

GN: There’s this fantasy of “Oh, it’d be so nice to not work, just write all the time,” but it’s unrealistic. And it’s not as nice as it sounds.

DN: Having a dearth of time is a tremendous motivator. I’m a world-class procrastinator. So knowing that the clock is running can really focus your thoughts. Even if you only have an hour to write, you can sometimes do three hours’ worth of work . . . if you’re not putzing around with the internet, checking your phone, et cetera. And I still do that stuff, too, because I’m a putz. But I feel like the amount of time I have to write is not nearly as important as just getting something down that day, even if I’m just nudging sentences around or toiling on a single paragraph. You’ve got to play the long game. If you put in the effort up front and work carefully and incrementally—rather than, say, rushing through stuff and meeting word counts and clocking hours—I think the results are going to be vastly superior, even if it takes you a little longer. If you bash out a book in six months, is that really better than writing a book in two or three or five years? Because you can’t publish a book a year, right? You shouldn’t publish a book a year.

GN: Why don’t you think so? I don’t disagree, but I don’t totally agree. I just want to hear you rage about this.

DN: I think there’s too many goddamn shabby books! A lot of people publish way too much, maybe because they feel an obligation to always have something to promote. Also, the mechanism for some independent publishing—print-on-demand, that sort of thing—really enables people to churn them out. And I think that’s to the detriment of the work.

GN: You work for a university, though not in an academic sense. You aren’t teaching, so your work doesn’t keep creative writing front and center. How does working a nine-to-five job affect the way you write?

DN: Well, I used to work as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. I survived several years of layoffs and furloughs and a collapsing industry, so I’ve had my share of desperate scrambling. Now I make my living writing about faculty research, mostly in the sciences, and I’m grateful that I never get anywhere near a classroom or rely on publishing to spruce up my CV or amass some kind of professional cachet. I’ve spent most of my adult life trying to build a sturdy firewall between my various employments and writing fiction. That frees up a lot of space for me—maybe it’s real, maybe it’s imaginary—to do whatever I want in my work. I cherish that freedom, even if it means I don’t get the perks of, you know, hobnobbing with other scrounging writers or nodding off at academic conferences. But man, the institutionalization of creative writing seems to me a real drag.

GN: This is an old soul of a collection. You lugged it around for years before it found a home. What influenced your organization and the collection’s trajectory? How did you decide which stories to keep and which to let go?

DN: Most of the stories were written over a period of about twelve years. There’s one, “Our Lady of Bleak Hearts,” that I started twenty years ago and kept tearing apart and restarting. Generally, the way that I’ve always worked is: I write a story; I’m not happy with it, so I’ll write another story to try to correct whatever I got wrong. Sometimes it’s a voice, sometimes it’s a character, sometimes it’s thematic. The funny thing is, I’ll write story A as a reaction to story B, which was already a reaction to story C, so they all web together in the end. Back in grad school, I wrote a story about a white-collar guy who tries to dabble in heroin and goes off the rails. It was just dumb. A bad story. Then I wrote “Beatrice and Bone,” which is about a couple of office temps who have kicked drugs and are feeling their way through sobriety in this sterile, white-collar world. That really deepened the stuff I was trying to do in the original piece. I eventually went back to that original story and used a couple sentences as a springboard for something new, which became “A Kind of Swimming.” This suburban dad, who’s had a terrible nervous breakdown and is under a kind of house arrest, sneaks out at night and unravels all over again. It’s a totally different thing, but I can still see a faint connection—a ghostly afterimage.

GN: I always think of William H. Macy when I reread that one. I was, like, casting your book as I read it. In case Netflix wants to . . .

DN: Lose some money.

GN: Can I have this bread?

DN: Yeah. But there were lots of stories that didn’t make the cut. Dozens. I wanted a short, swift book, so I kept the ones that spoke to each other. The gossipers.

GN: Your novel, The Great American Suction, came out with Tyrant Books a few years ago. The novel is louder, more slapstick and amplified. There’s a softening, a different sort of emotional center in Summertime. Stylistically, what shifted for you?

DN: I think the stories are more personal. With Suction, I was trying to do a lot of different things, and they’re all jumbled together. The jumble was kind of the point. When you write a story, it’s so compressed, so pressurized, you hopefully get an emotional rupture. Then you pile all the stories together into a collection and you get this cumulative effect, all these tiny detonations going off, one after another. It hits differently. The novel was rangier, more unruly, and more fatiguing, I think.

GN: Hearing you mention fatiguing prose reminds me of this wisdom George Saunders has shared in his Story Club a few times: “A story doesn’t have to do everything, it just has to do something.”

DN: The novel is really a book that’s built from other books. This was something George said to me when we were in grad school. He didn’t mean it as a criticism, but he said “your fiction feels like it’s inspired by other fiction.” And the first story that I gave him that he really did cartwheels over was “Beatrice and Bone.” He said, “This feels like it’s the most ‘you’ of all the work you’ve brought in.” And it’s telling that I slipped that story to him on the side. I didn’t even bring it to workshop because I didn’t want to see everybody rake it over. I just liked it too much. I mean, I don’t think I’m giving away any big secrets, but that story was about us. Soon I was writing more stories in that vein, you know, about you and me and the place I’d arrived at in my mid-30s as we got married. A lot of that fed into Suction as well: the idea of the guy who bungled his life and is struggling to get back on track. But I think the stories were more crystallized versions of that. Then my dad died—what, seven years ago?—and the more recent stories were clogged with grief and loss. So those are the twin poles of the book: love and recovery on one side, sadness and defeat on the other.

GN: What else is there?

DN: There’s Texas Roadhouse.

GN: We got so much fried food.

DN: This is intimidating.

GN: I thought you said “intimate.”

DN: This is an intimate cactus blossom.

GN: So you mentioned some of the stylists you like. Who else are you reading?

DN: Um, Gina Nutt?

GN: What else is there in addition to writing?

DN: I’m getting a dog.

GN: We’re getting a dog.

DN: I’m destroying this onion.

Gina Nutt is the author of the essay collection Night Rooms (Two Dollar Radio). Her writing has appeared in Denver Quarterly, Forever Magazine, Joyland, Ninth Letter, and elsewhere. She lives in Ithaca, New York.

More Interviews