Latin American Horror Stories | An Interview with Sarah Booker, Lisa Dillman, & Noelle de la Paz

Interviews

By Jimmy Cajoleas

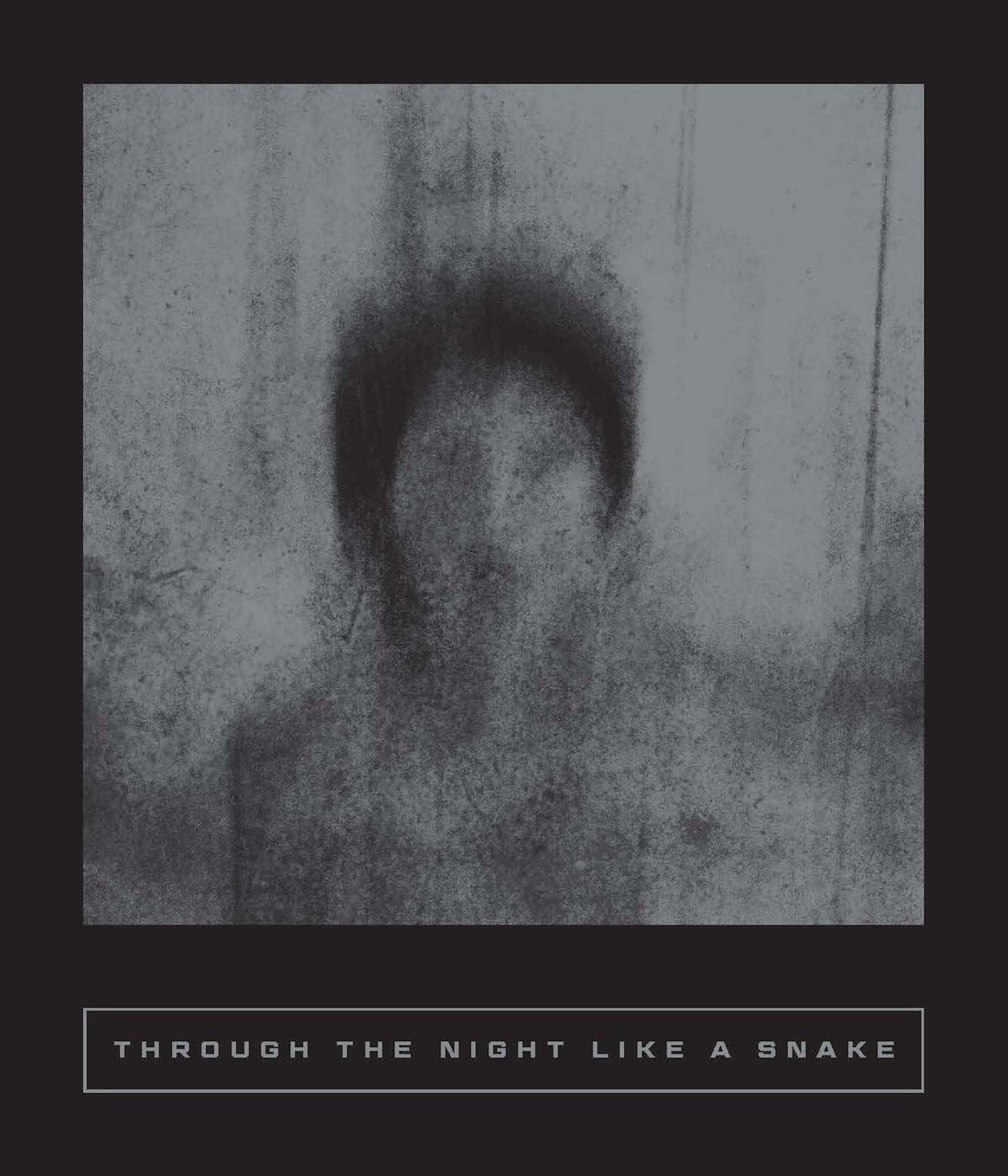

At some point in the last few years, Latin American horror became all the rage. My scary-story-loving friends and I eagerly anticipated each new release from writers like Samanta Schweblin, Mónica Ojeda, and Mariana Enriquez, sharing books and recommendations and arguing with the kind of enthusiasm that means something important is happening and we all feel lucky to be witness to it. The new short-fiction horror anthology Through the Night Like a Snake: Latin American Horror Stories, out now from Two Lines Press, is a wild journey through this emergent literary movement. The ten stories in this collection touch on classic horror archetypes, from cults to demonic possessions to body horror to serial killers to haunted houses, but recast in their own strange and eerie light that proves revelatory. Feeling both classic and somehow brand-new, these stories give us a particular vision of horror that is contemporary, exhilarating, and truly terrifying. I spoke with Sarah Booker, Lisa Dillman, and Noelle de la Paz—three of the translators who worked to bring this collection into English—about their experiences with the book, Latin American horror, and translation in general. This interview was conducted over email.

Jimmy Cajoleas: What do you make of this explosion in Latin American horror? Do you see it as a uniquely Latin American phenomenon, or is it a part of something larger?

Lisa Dillman: Well, first, I think it’s amazing—literally. And while there certainly is a lot of horror coming out of Latin America, I have a hard time saying it’s a Latin American phenomenon, in part because I don’t know what’s being written in other non-Anglophone parts of the world that may not be receiving as much attention or getting translated as much. Plus, it’s clearly not Latin American in its eerie appeal, as evidenced precisely by how much has been translated and well received and reviewed. So that automatically makes it part of something larger—the fact that it’s speaking to us in ways that have evidently touched a nerve.

Sarah Booker: Funny you should ask about this as I’ve spent the last month of the semester in both my Latin American literature and culture and advanced Spanish courses talking about this explosion of Latin American horror. We’ve read a lot of the leaders of this movement, including Mariana Enríquez, Mónica Ojeda, Liliana Colanzi, and Samanta Schweblin. On the one hand, I think this explosion of Latin American horror is a continuation of what has come before; in Latin American literature there has long been a fascination with creating literary worlds that toe the line between reality and something beyond. The obvious example of this would be magical realism (though I think it is overly used) as it is used to reflect a world and culture that is imbued with cultural beliefs and practices that expand perhaps Western concepts of reality. I think a lot of our contemporary horror writers are looking both to their predecessors in Latin America and beyond; there is a fascination, for example, with many of the gothic and horror writers outside of Latin America. What these Latin American writers are doing is drawing on some of these genres (especially the prevalence of the supernatural and/or unusual and the exploration of fear) and using them to examine experiences particular to Latin America. These writers are thinking deeply about embodied experiences in a particular time and place; they are responding to political violence, gender inequities, and environmental change, just to mention a few things.

I do think we are seeing a lot of Latin American writers working in this genre, but I’d be hesitant to say they are the only ones doing so. I think many of the recent Korean writers, for instance, are playing with horror in similar ways. What I do think we are seeing is a publishing phenomenon not unlike the one that created the Latin American Boom in the 1950s and ’60s. If this means we have the opportunity to read these amazing writers, to be getting work from Claudia Hernández, Camila Sosa Villada, and Giovanna Rivero, then keep it coming!

JC: What drew all of you to horror translation? What are some of the challenges or interesting problems in evoking the horror of these stories?

LD: The truth is I’m not actually drawn to translating any specific type of fiction; what I’m drawn to is good writing, be it horror or farce or detective novels. What attracts me is fiction that on some level is making a commentary. And translating it generally shares the same sorts of challenges. Namely, figuring out both where and especially how to be less literal, when more lexically accurate renderings would result in the narration being “off.” For instance, in several places Antonio Díaz Oliva has written passages that are poignant in Spanish; translated in a way that hews very closely to the original, some of them would become hokey or more cliché in English. So it becomes a question of figuring out how to pull back and show restraint. And I realize that sounds a bit vague, but stylistics are a bit vague. And it’s not easy to point to a word or an explicit reference as an example because what we’re talking about is a whole slew of really minor things which, added together over the course of a paragraph or a page or a chapter, create the mood and the tone.

SB: I’m not sure I would say I translate horror exclusively, nor would I say I am drawn to reading mainstream horror. What I like about the (I suppose) more literary horror, is that there is often some sort of experimental or creative speculation and use of language. I find that I am particularly drawn to writing that feels embodied (in that there is a focus on the body) and that does something interesting with language or the form to tell a story. I appreciate writing that makes the reader think about something differently, and I think that is what a lot of these Latin American writers are doing really well. Of course, unusual uses of language in Spanish present challenges in English in that there is often a need for creative solutions that likely go beyond a literal rendering. I’ve also had experiences in which the text I’m translating is disturbing or even traumatizing (I experienced this a lot with my translation of Mónica Ojeda’s Nefando), and in those cases it has been important to strike a balance with the text and to give myself some space.

Noelle de la Paz: When selecting “Soroche” by Mónica Ojeda as our submission for the anthology, Sarah and I talked about what positioning the story within a horror collection said about the piece as well as the genre. While “Soroche” doesn’t revolve around some of the more common perceptions of horror—serial killers, supernatural/evil forces, the stuff of jump scares—we were taken with the way Mónica immerses the reader in a visceral horror of abject humiliation, particularly as experienced through the lens of women’s relationship to their bodies and how they are perceived. And while the characters don’t express fear overtly, there is a nagging undertone of the ways fear keeps us from confronting shame and the parts of ourselves that disgust us, how fear compels us to do everything to keep our basest impulses as bay, the fear of judgment, of ridicule, of being ostracized. I think the question of what makes horror horror—what makes any genre that genre, for that matter—is important to keep simmering on the back burner to ensure evolution and innovation and hold space for a range of perspectives, which is particularly essential for a genre predicated on grappling with the fear of the unknown.

JC: Lisa, the story you translated, Antonio Díaz Oliva’s “Rabbits,” takes place amid the backdrop of Chile’s violent political struggles of the 1970s and ’80s. What were the challenges of translating a politically charged story into a different language? Was there an impulse to clarify any concepts or details for a foreign audience?

LD: I love this question. There was nothing as far as concepts, per se, that I felt a need to clarify, but in one or two instances I did make adjustments to details. As you said, the story is set in Chile, and we have this eerie enmeshing of the horrors on the commune and the horrors outside the commune: the metaphorical and the literal, the historical and the personal or familial. Largely, the challenges were stylistic—of the sort I mentioned a minute ago—rather than historical, since ADO actually names Chile and mentions specific years, and so on. But in deciding how much to explicate in a translation, you generally sort of gauge your audience and their likely background knowledge. And while there were a number of things I would not expect readers to know, “Rabbits” provides enough context to draw the correct conclusions and make sense of what’s going on. For instance, at one point the protagonist wonders why the commune members, after they were discovered, weren’t all taken to Dawson Island. Even if you’ve never heard of Dawson Island, you can surmise what would have happened there because it’s named together with the National Stadium. I’m banking on readers knowing the kinds of things that happened during the dictatorship rather than surmising that the protagonist maybe wonders why they weren’t taken to a baseball game. I’m being tongue-in-cheek, of course, but it’s true. There were, though, a couple of places where I used a stealth gloss (thank you, Jason Grunebaum, for this term), which is where you slip in a phrase not present in the original as a way to clarify something. So, for example, when the narrator refers to Pinochet simply as “Pinocchio,” I glossed that. The English reads: “It was probably some soldier in civilian clothing, delegated by Pinochet, aka Pinocchio, to ensure that the community remained isolated.” The Spanish says only “delegated by Pinocchio.” And I did debate this. Was the gloss necessary? They both start P-I-N: Would it have been easy enough to surmise? In the end, I was concerned about introducing an unintended humorous connotation, breaking the tone.

JC: So many of these stories are about women, focusing on the darker sides of things like maternal care, friend groups, and fears about the body. These experiences seem both local and specific, but also universal. How do you see these stories affecting English-speaking audiences, and who do you see as their audience?

LD: Yes, isn’t it marvelous? Immediately what comes to mind is my friend Tonya. I have a vivid memory from twenty-some years ago, when she was pregnant. She said something about the “glow” pregnant women have being bullshit, that if anything it’s a patina of sweat from being overheated. And she was furious that all of the mommy-to-be type books idealized pregnancy and seemed to be, quite literally, a fiction invented by men. As far as audience goes: one of the things that makes me hopeful right now is talking to my students and hearing them express their feelings about gender, feminism, sexism. They speak so openly about their lived experiences and embodied experiences and their bodies and the ways their bodies can betray them, imprison them, or free them. This semester the students in my advanced translation seminar are translating fascinating stuff for their final projects. Stories about a world in which all humans are intersex. Stories about pseudo-Siamese twins in which one “head” constantly reflects on what her body is doing, while the other one is the pretty one who gets all the attention. Stories about self-mutilation as a form of post-trauma self-soothing. It’s amazing, it is all so embodied. And while most of it is Latin American, the three stories I just referred to are from Spain. Ten years ago my students would have rejected this type of writing. We’re in a different time now. They want to talk about alienation and disengagement and how totally effed up the world is. It’s one of the few things, in our current political landscape, that gives me hope. So, I’d say we have an entire college-age generation who are an engaged audience.

SB: While a lot of these stories are responding to culturally specific experiences (I’m thinking of “Soroche,” for example, which is very much a critique of Ecuadorian social class divides), many of the experiences can be quite universal. As you list out, complex social dynamics and relationships of care and body angst occur in all cultures. I see English-speaking audiences relating to these stories while also taking the time to consider the cultural context. I’d be cautious about assigning a specific audience for this work or any literature, really, as the wonderful thing about literature is that it can be shared beyond personal identity.

NDLP: While the women’s daily existence seems totally separate from the natural world, in “Soroche” it is precisely the Andean landscape that brings them to the central confrontation in this story, a confrontation with the dissolving boundaries between beauty and ugliness, life and death, human and animal. The climb puts a growing distance between them and their lives that revolve around social status mediated by digital technology, bringing them closer to something else—a clarity, perhaps. I think tensions between seemingly polarized realms are often calling out and collapsing a false binary. Technology and nature, modern and ancient, contemporary/digital lifestyle and folk/indigenous beliefs. It makes me think of what’s been said of magical realism, how rather than “blurring the line” between what some think of as two opposing modes (the “magical” and the “real”), it’s an expression of how certain cultures experience and hold space for both in the same breath—less like a line, more like an ecotone. I think something similar can be said about how folk beliefs are seen as remnants of the past, as static history, rather than as something that persists and adapts in this modern world, and in fact does not merely coexist but can bring essential meaning and perspective to what is positioned as more advanced, or at best, separate.

JC: A common theme of folk horror is the way a rural or remote landscape acts as a destructive force on the more urban visitors. In “Soroche,” it is the landscape that makes the characters sick (or brings out the hidden sickness within them). Soroche itself is a term specific to illness brought on by the Andes. I wondered if you could discuss that word and its relation to the story.

SB: Soroche is a fascinating term, one that comes from Quechua, an Andean indigenous language. It is also one of many terms that have developed in the region to describe the physical experience of existing at high altitude. Ojeda’s story actually starts with one of the characters—Viviana—running through all the different terms and phrases used to describe altitude sickness. My co-translator, Noelle, took the lead on Viviana’s monologues and so was the one to put together the list in English, which reads beautifully as: “They call it air sickness, altitude sickness, mountain sickness, sick from the highlands, sick from the plateaus, sick with soroche.” What comes through here is that there is such a clear connection between the landscape and the corporeal experience. Noelle and I had a lot of fun talking through all these different phrasings and considering what English would allow. We really focused on maintaining that element of sickness, as it is so key to the story.

The altitude sickness does indeed serve as a metaphor for the condescension expressed by the women in this story, both toward those of a lower social class (these women are upper class) and then toward one of their own as soon as she shows her vulnerability (both in her physical appearance and in the social faux pas of making a sex tape; there is quite a lot of victim blaming that takes place).

JC: The story departs from the traditional realm of folk horror in its use of technology and social media. Specifically, the shame that Ana feels over the leaked sex tape. This conflict between the new digital world and the ancient natural world seems essential to this story. What do you make of this clash of technology and landscape?

SB: Interesting question! I think it speaks to the increasing dominance of technology in all our lives across the world, even in a region so culturally dominated by a natural landscape. This makes me think about Chilean writer Alberto Fuguet’s famous essay titled “I Am Not a Magical Realist,” in which he expresses frustration that he quickly finds that to publish in the US he can’t escape the expectation that he write in the vein of Gabriel García Márquez. He complains that this genre creates the false interpretation of Latin America as primitive and ignores that it is a modernized place (for better or for worse). I think in this story (and throughout the collection Las voladoras, where this story was originally published) too, we see a resistance to a singular conceptualization of the Andes. At the same time, technology is the source of the horror in this story, or at least it is the vehicle through which these women are able to project their violent feelings toward one another, thus protecting themselves.

JC: Ana’s frank discussion about her horror at her own body is written in language that is visceral, powerful, and disturbing. What was the experience of translating this section?

SB: Here I really want to give my co-translator Noelle all the credit. When we decided we wanted to co-translate a story, we chose this one because of the distinct monologues. We thought this would be a way to really take advantage of having two translators as this would allow us to each channel the different voices. Noelle was really excited to take on Ana’s monologues as she wanted to work with the graphic language. We revised the translation together and spent a lot of time talking through the specific rhythm of Ana’s monologues and the specific vocabulary used and how Noelle had beautifully rendered that into English. All the bovine imagery was quite interesting and disturbing.

NDLP: I think of translation as the closest read you can give a text. I experience it as a deep study on the word level, the phrase level, the sentence level. Because “Soroche” is structured as monologues, translating Ana’s sections was a particularly disturbing study of being so close to not only her thoughts, but her body. And not her body as a whole, but, for instance, her toenail and how it’s cut, the texture of her inner thigh, the contortions of her face muscles, among other parts. It was an experience of sustained discomfort, a strange blend of zooming in as well as dismemberment. As a literary translator, the task is to pay attention to everything a writer pays attention to in word choice, character voice, rhythm. On this front, capturing Mónica’s lyricism (she is also a poet, and that sensibility is also present in her prose) meant constructing a sonic quality that is almost hypnotic, even beautiful, the language pulling you in at the same time as what it’s saying repels you—again, a tension; again, a collapse and coexistence of seeming opposites.

JC: Lisa, though bearing many of the telltale marks of folk horror (cults, the threat of nature in the countryside, ritualized murder, etc.), “Rabbits” breaks from the mold by showing the outside world as more horrible than anything the commune can come up with. What is it about this sentiment that resonates so strongly in Latin American horror?

LD: That’s really interesting. So, as far as resonating, there are obviously political undertones. The backdrop of dictatorship resonates with so many people who lived either through it or parallel to it. But honestly, I’m feeling like it’s pretty damn resonant in the US, no? There’s a kind of irony, maybe, to the idea that younger writers are perhaps evoking things from their childhood, from their parents’ generation. And for gringos, now, it’s resonant because it feels like . . . our future? The destruction of institutions, of the free press. Newspeak. That’s horror right there. But I’m also curious about your saying that the outside world is more horrible than the commune. I saw the outside as being almost just another form of horror—one that was unfamiliar, rather than familiar.

JC: Rabbits are such a potent occult symbol across cultures, in the luck of the rabbit’s foot and the promise of regeneration come spring. Why do you think it’s such an effective motif in this story?

LD: I have two answers to this question. The first one is that to me, they work so well because of the sexual overtones. That first night they crop up, when Raquel and the protagonist have just finished dinner, they just seem to multiply like . . . rabbits. But not sweet, soft bunnies—these are big, dirty, quivering things with red eyes. Then we have the juxtaposition of Raquel and the protagonist in the city on their formative experience, spending a lot of time fucking like . . . rabbits. But of course everyone wants to kill the rabbits: shoot them, throw them in ditches, smash their heads, and so on. It’s hard to overlook—or overstate—the horror of that collocation. What or who is being killed? The kids in the commune? Their “awakening”—whether sexual or intellectual? The young couple’s future? So many possibilities, all of them horrific. It’s pretty chilling. My second answer is that, personally, I didn’t even think of the occult with reference to them. And you’re right of course; rabbits symbolize so many things. And one sign of good literature, I think, is how open to interpretation it is. There’s not a right answer. So if you, or other readers, take away entirely different things, that’s great and equally valid, and all I need to ensure is that my translation leaves room for all of those interpretations. I’m interested in hearing your response to this question.

JC: Lisa, since you said you’re not drawn to a specific type of literature, is there anything entirely different that you’re translating or interested in translating now?

LD: Yes! I have been obsessed with Cristina Cerrada’s prose for several years now, and I cannot believe she hasn’t been translated. Cerrada is from Spain and has written a trilogy about young women from unnamed war-torn countries living in exile. They’ve all survived horrific experiences, but these experiences are related through allusion and incredibly spare description; there’s absolutely nothing graphic or gratuitous about it. In fact, it’s very poetic. It’s absolutely astonishing—desolate, minimalist. Chilling and “horrific” in its own way, though clearly not horror.

Jimmy Cajoleas was born in Jackson, Mississippi. He lives in New York.

Sarah Booker is an educator and literary translator. Her translations include Mónica Ojeda’s Jawbone, Gabriela Ponce’s Blood Red, and Cristina Rivera Garza’s New and Selected Stories, Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded Country, and The Iliac Crest. She has a PhD in Hispanic Literature from UNC-Chapel Hill and is currently based in Morganton, North Carolina, where she teaches Spanish at the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics.

Lisa Dillman is translator of some thirty novels, including those by Yuri Herrera, Pilar Quintana, Alejandra Costamagna, Andrés Barba, Sabina Berman, and Eduardo Halfon. She lives in Atlanta, Georgia, and teaches in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Emory University.

Noelle de la Paz is a writer and literary translator. Her work appears in The Recluse, Kenyon Review, and elsewhere, and in the exhibitions Otherwise Obscured: Erasure in Body and Text (Franklin Street Works) and Boulevard of Ghosts (Local Project). She was a 2021/22 Emerge–Surface–Be Fellow at The Poetry Project and has also received support from Brooklyn Poets and the Queens Council for the Arts.

More Interviews