Lunatics and Lost People

Reviews

By Marshall Shord

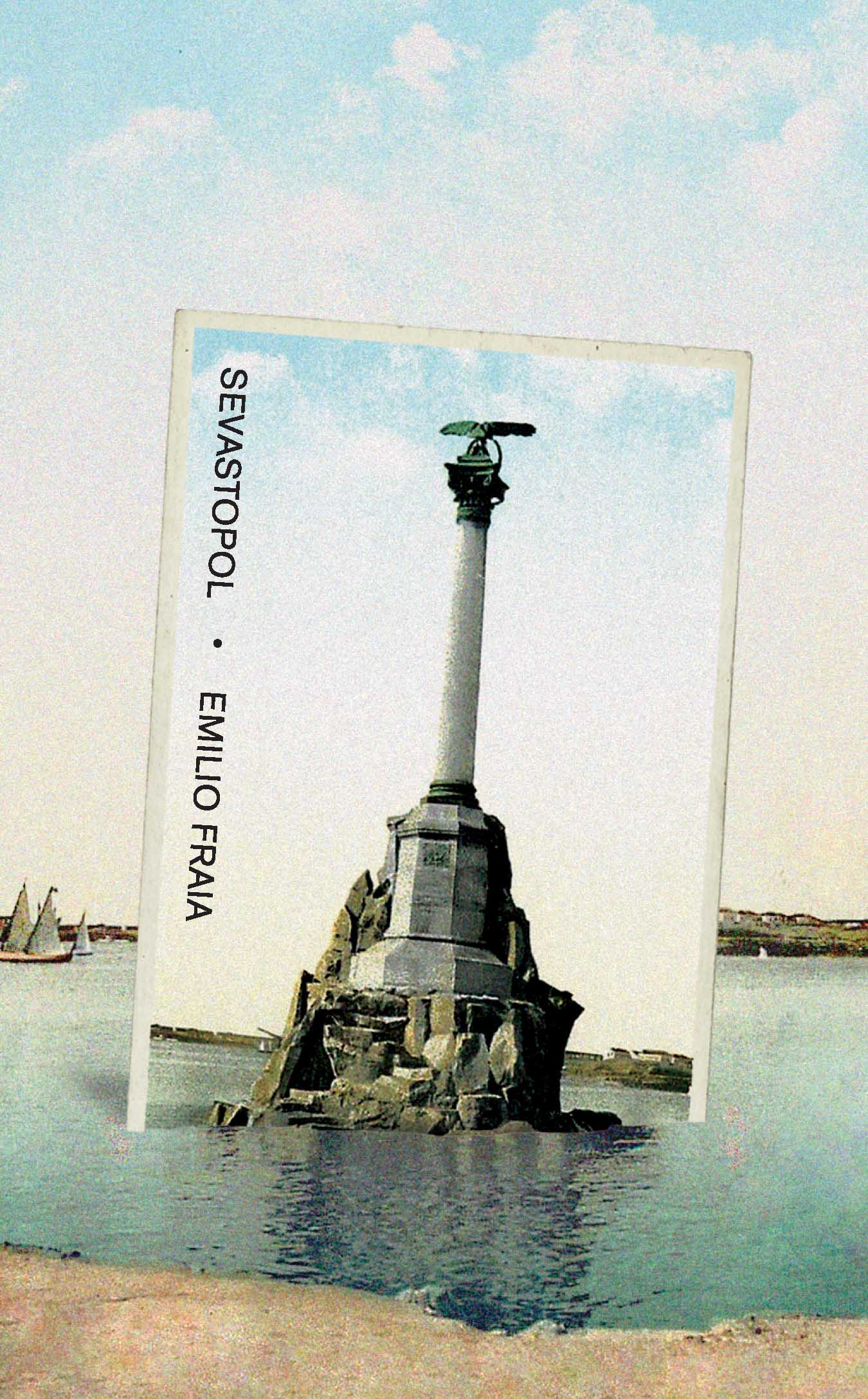

The characters in Sevastopol, Emilio Fraia’s brilliant triptych of stories, are as familiar with the sense of what-could-have-been as with the ache of a phantom limb. Loss defines each of them, and, in a way, is also what keeps them going. They haunt their own lives, seeking out what they have lost, not because they think that finding it will bring back all that has gone, but because they can think of nothing better to do. One way to define a ghost is as a compulsion that has outlived the one who bore it.

Smuggled in under the cover of these stories of, as one character puts it, “lunatics and lost people,” is a portrait of Brazil in precipitous decline, riven by racism, inequality and violence. Fraia provides the reader with only a few outright glimpses of this covert narrative, preferring instead to dress it within the specific context of each story. At the same time, he deploys recurring images—a demon seeking to escape its earthly prison, streets too wide to cross—and a uniform atmosphere of dread to bind the stories into a cohesive whole.

Although they all belong to the upper classes, Fraia’s characters—a mountain climber, a property owner, a young museum worker—feel themselves far from the lives their privilege had promised them. One character thinks about “the big picture, about my generation, crushed by another ten, fifteen years of paralysis.” Another sees her friends “trapped inside office buildings, locked in the struggle for promotion.” São Paulo is described as “a giant space station, a forgotten corner in the vastness of the heavens.” One gets a sense that for these characters—and maybe for everyone—there’s no escape from the nightmare of the modern world.

“December,” the first story, revolves around a young woman named Lena who once dreamed of scaling the highest mountain on each continent. But, after an accident on Everest, she has lost both of her legs. She now makes her living as a motivational speaker, using her loss to inspire others to “overcome adversity.”

One day, getting some air in her neighborhood, Lena enters an art gallery and comes upon a video installation. The images she sees on the screen are familiar to her: “This was my story.” She does not know the artist and cannot understand how images from her life (“albeit somewhat distorted”) have come to be projected there in front of her. Although she feels a sense of violation at such an intrusion into her private life, the greater issue is that the video itself threatens to become history, thus painting over the narrative that has sustained her—that of perseverance in the face of unimaginable pain.

In the second story, “May,” Nilo (as in, nihilo, nothing) is losing his memory along with his inn in the mountains, both victims of the passage of time. His buildings are falling down, his neighbor is imploring him to sell, and his sense of self is slowly disintegrating.

Two weeks prior to the start of the story, a man and a woman had arrived after driving aimlessly through the wilderness. The woman, Veronica, reluctantly stays for a week before returning to São Paulo, but the man, Adán, hangs around for a time. Before he leaves, Adán tells Nilo his life story—with the caveat that “no one learns anything from any story.” A story is, rather, “a cry for help.” No one could be less qualified to help than poor, bewildered Nilo.

What happens instead is the opposite, an act of reassurance on Adán’s part that the emptiness Nilo feels—that sense of fading away—is not exclusive to him. Although Nilo doesn’t know it then, Adán is preparing to go at that very moment, leaving Nilo to wander the empty halls of his inn, alone again, without even his memories to comfort him.

The final story, “August,” is the most conventional of the three. Nadia (nada, almost) is assisting a has-been dramatist named Klaus in researching his play about a fictional Russian painter. For Nadia it’s a chance at an out from a life which, to that point, has proven underwhelming. She quits her job, despite Klaus’s disapproval (“I’m not paying you a penny more.”), and spends her time diving into the historical milieu of the play when not drinking or taking acid with Klaus. Although Klaus makes, to put it mildly, a worrying totem of the creative lifestyle, she’d still rather sleep on an inflatable air mattress in his crummy apartment (which, delightfully, “looked like a room in Count Dracula’s Castle”) than return to her own apartment filled with reminders of her inconsequential existence—“a pathetic bookshelf,” “a pitiful little landscape.”

After the play closes (it is an embarrassing flop), Klaus tells Nadia that he is leaving. She is left with no play, no job, and no friend. Her only connection to the world that came before Klaus is a baffling sketch she had shared with him early in their collaboration and which he called “lousy.” The story ends with her tinkering with it again, stuck in a creative loop, telling the same story in different iterations, changing only the setting and the time, because “people always tell the same stories, even when they try to tell new stories.”

A single human life holds within it an infinite capacity for loss. Thomas Hardy writes of the plight of Michael Henchard in The Mayor of Casterbridge, “All had gone from him, one after one, either by his fault or by his misfortune.” As Sevastapol masterfully demonstrates, all one can do against time’s attrition is organize the losses into a story of the self. But even that—one’s coherence—is no real bulwark.

Marshall Shord lives in Maryland. He is currently at work on a novel about the formation of the CIA.

More Reviews