Machinic, Unloving, Graceless

Reviews

By Conor Hultman

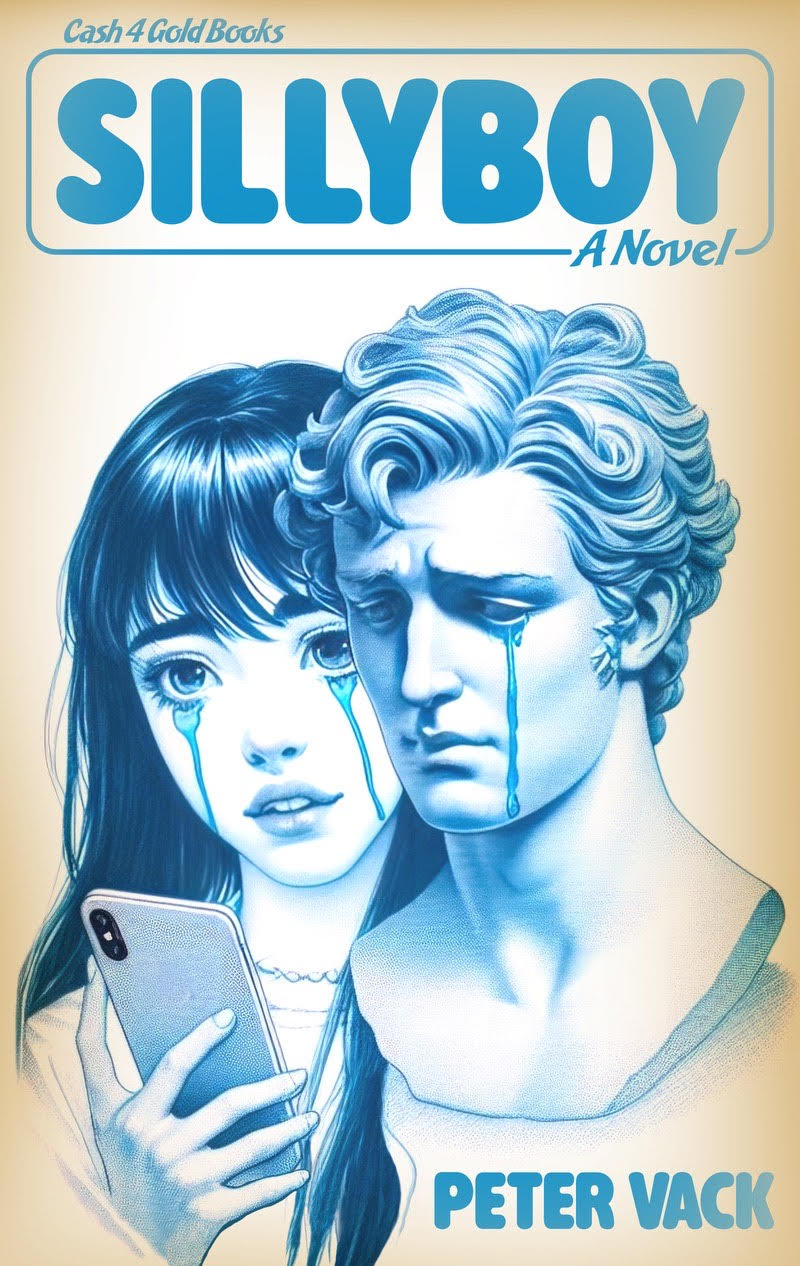

It takes reading all the way to the end of Sillyboy (Cash 4 Gold Books) before the first line truly makes sense: “If only he could remove his skin.” Peter Vack’s debut novel is largely about the problem of ego. How is a person simultaneously endowed with free will, perception, and self-perception supposed to live with others, in a world cursed with technology that abuses these faculties?

Vack traces this problem through the story of the failed relationship between the protagonist, Sillyboi (spelling changed in a narcissistic attempt at individuation), a twenty-eight year old aspiring actor in New York City, and his tattoo artist girlfriend, Chloe. The narrative starts in the middle of the relationship, flashes back eventually to its beginning, and then sees it out to the end. Sillyboy is written in a Dos Passos collage style of dialogue, thoughts, social media posts, texts, Future rap lyrics, and the protagonist’s abortive screenplay. The origins and intentions of all these words blend together, creating a manic simulacrum of the machinic, unloving, graceless media landscape everyone navigates today. A sample from early on:

Chloe took out her phone and opened Instagram. . . . I have more followers than most (3,456) but far less followers than I will have in a year, Chloe thought. In a year, my art will be so great and I will be so hot, my profile will boast the life-affirming “K” (10.5K is the number she’s manifesting), the “K” that makes you cool. I will be seen. I will be desired. I will be liked and commented on.

Reading the novel induces the panoptic paranoia of the internet, heightened through the narrator’s interiority and the trappings of romance.

The plot features all the hallmarks of a classic love story: jealousy, longing, infidelity, false abandonments, reconciliations. Sillyboy feels like a dark Daphnis and Chloe, a perverse remake where the lovers are doomed to fail. Maybe the naming is intentional. While Sillyboi and Chloe obsess outwardly over their semiotic minefield, hunting clues to the other’s cheating or divining fame in Instagram posts, the burden of their histories weighs like dark mirrors inwardly. In one scene, Chloe is awake in bed beside a sleeping Sillyboi, torturing herself with thoughts of her mother. “My mother, Chloe thinks, is the kind of woman who would participate in genocide if she were commanded to do so. Women to the right, men to the left.” The hypermass of these twin consciousnesses, the self and the persona, magnify each other until the characters are smudged into the less-than-real, the uncanny. The memetic referencing, the postironic slang, the lack of boundaries between humor and seriousness that make up the novel are there to put weight on the impact of the tragedy. The reader is lured into sympathizing with Chloe and Sillyboi, and in that sympathy feels what anyone feels when confronted with something as permanent as loss in our hypermodern desert of the real: This can’t be happening to me.

Sillyboy’s style gives the impression of non-effort, a cool and unlabored prose fitting its smaller-than-life characters and banal setting. This impression is revealed as false when paying any attention almost anywhere. As an example on the subject of consciousness, after an episode of Chloe cheating on Sillyboi:

Once finished, Chloe is still preoccupied with identifying which part of the evening Sillyboi would hate the most. Would it be how Alex held either side of her face as he climaxed? Would it be his semen, now in her cervix, fighting to the death with her IUD? Would it be his aggression? Would it be how she cried “daddy?” Or would it be how all of the expressions and sounds she made were likely identical to those she makes at home with him? No, none of this is damaging enough. What should boil his fury to the point of psychosis would be to observe them now: her body wrapped around his, the room silent but for their breath in rhythm.

Reminiscent of the example Sartre gives of the voyeur at the keyhole in Being and Nothingness, the passage illustrates how knowledge of being perceived changes one’s being itself. From a “pure consciousness of things,” once perceived, the Self grapples with the Other: “It means that I am suddenly affected in my being and that essential modifications appear in my structure.” The psychoanalytic stuff is so obvious as to be a diversion—from the aforementioned mommy issues and daddy role-play, as well as discussions on “teen porn” categories, mother-surrogate girlfriends, and their deleterious effects. Sillyboi happens to come from a family of wealthy New York analysts. It’s all lampshaded to render significances more opaque, even the lampshading itself. “You’re wrong. There’s no symbolism. That’s the point, actually. It’s all right there,” says Chloe, in an argument with Sillyboi about the misogyny in Future’s Dirty Sprite 2. This, in a novel rife with symbols—tattoos (“How can you exist in the world, covered in tattoos, and expect people not to look at them?”), anuses (“Chloe and Sillyboi eat egg sandwiches with the familiarity of people who have tasted each other’s asshole”)—where even the object of the novel itself is subtly ridiculed (“Sillyboi’s text to his analyst: the My Struggle of pathetic self-evisceration”). Instead of doing the modernist shtick and planting a million overt symbols in the hopes they collide into some meaning, Vack has written a story in an understated vérité that denies the meaning during its making. Call it autofiction, call it confession, but call it brilliant.

Conor Hultman lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

More Reviews