Motherhood Is a Life Sentence

Reviews

By Lori Feathers

What should we call a woman who lacks maternal feelings for the child she birthed and raised? Why is the idea of a “maternal bond” so sacrosanct that its absence or deficiency seems perverse, that we consider the woman in question monstrous, bereft of an instinct so natural and fundamental that she defies explanation?

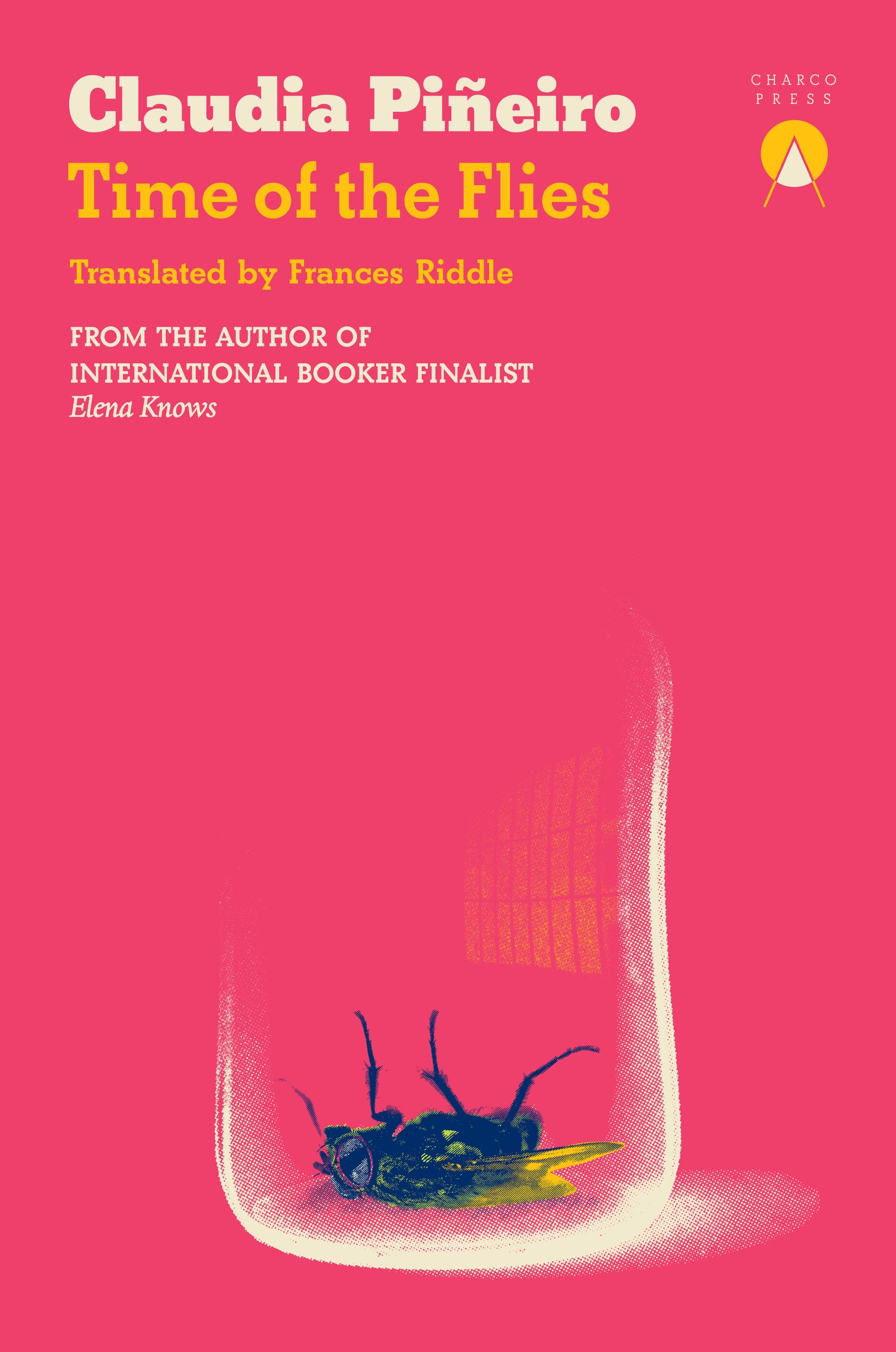

These are questions that bring moral heft to Claudia Piñeiro’s Time of the Flies, a literary crime novel accented with commentary from a chorus of boisterous feminists who are following along as the story unfolds.

Inés is a year out of prison, having served fifteen for the murder of her husband Ernesto’s lover, Charo. (Piñeiro detailed the story of the murder is her earlier novel All Yours, published by Bitter Lemon Press in Miranda France’s 2011 English translation). Inés has partnered with her friend Manca (so nicknamed due to her crippled hand), who served time with her for minor drug trafficking. They are the proprietors of “Females, Flies, and Fumigations,” or FFF, a company in which they each pursue their own line of work: Inés as a pest control technician offering nontoxic fumigation services for flies and other insects; Manca as a private investigator whom suspecting women hire out to uncover their husbands’ infidelities.

Early on we are introduced to the prospective crime when the wealthy Buenos Aires television producer Susana Bonar, a first-time customer for Inés, offers to pay her to procure a certain extermination poison so that Bonar can murder her husband’s lover. Bonar says as soon as she arrived she recognized Inés from the television coverage she saw years ago of Inés’s conviction for Charo’s murder. Bonar believes that in Inés, she has found a kindred spirit: “Any other fumigator, anyone who doesn’t understand this pain, would turn me in. I know that you understand me.”

And Inés does identify with Bonar’s pain, but she doesn’t want to be involved, doesn’t want to relive the past. After Inés’s refusal, Bonar presents an envelope fat with dollar bills, “an advance, with no obligation,” for Inés to simply consider the job and Bonar’s promise of a lot more money if Inés follows through getting the poison. Inés takes the money.

She confides to Manca about Bonar’s proposal, seeking her friend’s advice and talking through the risks of being implicated in the murder Bonar is planning. Manca is suspicious of Bonar, thinking it an uncanny coincidence that she randomly hired Inés. But before Manca can investigate Bonar and quell or support these suspicions, Inés hastily accepts Bonar’s assignment after she finds medical papers that Manca hid from her that diagnose her friend with breast cancer and reveal that Manca cannot afford timely treatment.

Furthering Manca’s suspicions is her discovery that Bonar is friends with Inés’s estranged daughter, Lali—or Laura, as she now prefers to be called—who has never forgiven her mother for abandoning her when she was jailed for the murder of Charo. It is this void, where a mother-daughter bond of some sort is supposed to exist, that Piñeiro probes to provocative effect.

The novel is full of Ines’s recollections of her former family life with Lali and Ernesto, mostly unpleasant. Her self-justifications for murdering Charo despite knowing how this act and her subsequent prison time will damage seventeen-year-old Lali are impossible to support, especially given that Inés knows when she murders Charo that Ernesto, too, is headed to prison for his act of violence against another woman who became entangled in his extramarital love affair.

But Inés doesn’t see her incarceration as the point at which she stopped being a mother to Lali; rather it is later, when Lali came to visit Inés in prison for the first time with papers to sign the house over to her: “Laura took the house and never returned. And that ended up having a positive effect, it allowed me to close the book on motherhood once and for all: without a daughter, there’s no mother . . . Childbirth can’t be denied but motherhood can.”

Underpinning Inés’s excuses is the more controversial point that she does not, and likely never did, feel maternal love for Laura, nor does she believe that she should feel it: “I didn’t enjoy being her mother. Birthing her was easy, she came out in just a few pushes; I mean after that, ‘nurturing,’ as they say now, our life together. They were very harmful in that house, and I don’t mean only Ernesto. I am only a mother on paper, because motherhood is a life sentence (but I don’t feel like a mother anymore).”

Inés’s position entices us to question society’s presumptions about maternal bonds and even why these presumptions persist. Does biology program a pregnant woman’s brain to have an emotional attachment to her child? If not biology, then is our idea of a universal maternal instinct solely a product of societal expectations? Is the mother-child relationship intrinsically different from the emotions and responses that attract or repel any other two people?

Time of the Flies is not the only novel by Piñeiro to ask unorthodox questions about motherhood. In her novel Elena Knows, translated by Frances Riddle and shortlisted for the International Booker Prize, the title character, a sixty-three-year-old woman suffering from advanced Parkinson’s disease, makes the extreme effort to travel across Buenos Aires to talk to Isabel, a woman she has not seen for twenty years. Elena wants Isabel to know about the death of her daughter, Rita, and to get Isabel’s help to investigate Rita’s death. Elena believes that Isabel must feel indebted to Rita for preventing her from having an abortion all those years ago. But Isabel is not grateful. Instead, she is convinced that having her child, Julieta, ruined her life. Indeed, Isabel has never had any maternal feeling for Julieta, despite living with and dutifully performing the tasks expected of mothers.

Interspersed in Inés’s story are seven brief chapters where we drop in on a female chorus who argue and banter about the scope and objectives of feminism. The chorus’s colloquies include quotes from texts of contemporary feminist writers and underscore the many questions the novel presents. They also insert humor and playfulness into the otherwise thorny and painful topics of maternal responsibility; the systemic and wide-ranging effects of the patriarchy on women’s emotional, professional, personal, and family lives; feminism’s reaction to transgenderism; and targeted aggression by women against fellow women by those who wear the mantel of empowered feminism. Here Piñeiro is adept at capturing the back-and-forth that occurs when people argue positions before they have figured out what, exactly, it is that they believe.

Each of the choral chapters opens with a quote from Euripides’s Medea, and this is significant in terms of the similar rage and precarity felt by Medea and Inés when their husbands choose other women. Inés’s act of revenge against Charo and Ernesto indeed draws comparison to Medea’s murder of her husband Jason’s new bride. More interesting, however, is the question of whether Inés’s abandonment should be regarded as a metaphoric murder of Laura, much as Medea murdered her sons.

It is unlikely that Laura would see it that way because her fate is a much happier than that of Medea’s slain sons. Some of the most hopeful parts of the novel are descriptions of Laura’s home life with her thoughtful and considerate husband and two children. Laura finds her professional and personal life fulfilling and generally happy, much to Inés’s shock when she secretly observes the family one evening. However, from Inés’s perspective, Laura is dead to her.

There are suggestions that Inés has not effortlessly shed her maternal responsibilities: in times of high stress, she sees a “fly” buzzing in front of her left eye. The eye doctor explained that her “fly” is merely a “floater,” dead eye cells, but Ines refuses to believe it, refuses to consider that the fly is symptomatic of her subconscious guilt about the past.

Inés respects the lives of flies and knows a lot about them from her time reading in prison. Flies also played a prominent role in her own troubled childhood. She recalls her mother’s failed anxious attempts to keep flies out of the house, and when she failed, Inés’s father procured an electric fly zapper, burning his hand on it just before leaving Inés and her mother for good. One fact that Inés knows about flies has special resonance for the novel: flies experience time four times slower than humans do. At this much slower pace, perhaps Inés would have acted less rashly and not murdered Charo; perhaps she would have had the patience and grace to try to mend her relationship with Laura.

Time of the Flies entertains and provokes in equal measure. It wears its feminist positions patently but also exposes their weaknesses. Piñeiro, along with her talented translator Frances Riddle, gives us a novel that feels original, even as the gender issues it presents are as old as Eve and her patriarchal Adam.

It is tempting to see in Inés a woman who protests too loudly about not loving her child and resenting motherhood; to believe that Inés is in denial. I reject this interpretation, preferring the morally confounding Inés, a woman simply true to her nature, however ugly. My Inés is a prickly, difficult woman who lives with regrets but remains stingy with her affection, specifically toward the one female that society demands she love unceasingly.

Lori Feathers is a writer and podcaster in Dallas, Texas, and a co-owner/founder of Interabang Books where she is the store’s book buyer. She co-hosts the critically acclaimed books podcast, Across the Pond, is founding Chair of the Republic of Consciousness Prize, US and Canada, a prize honoring the work of small publishers, and co-creator of the Inside Literary Prize for incarcerated persons. For six years she served on the elected board of the National Book Critics Circle.

More Reviews