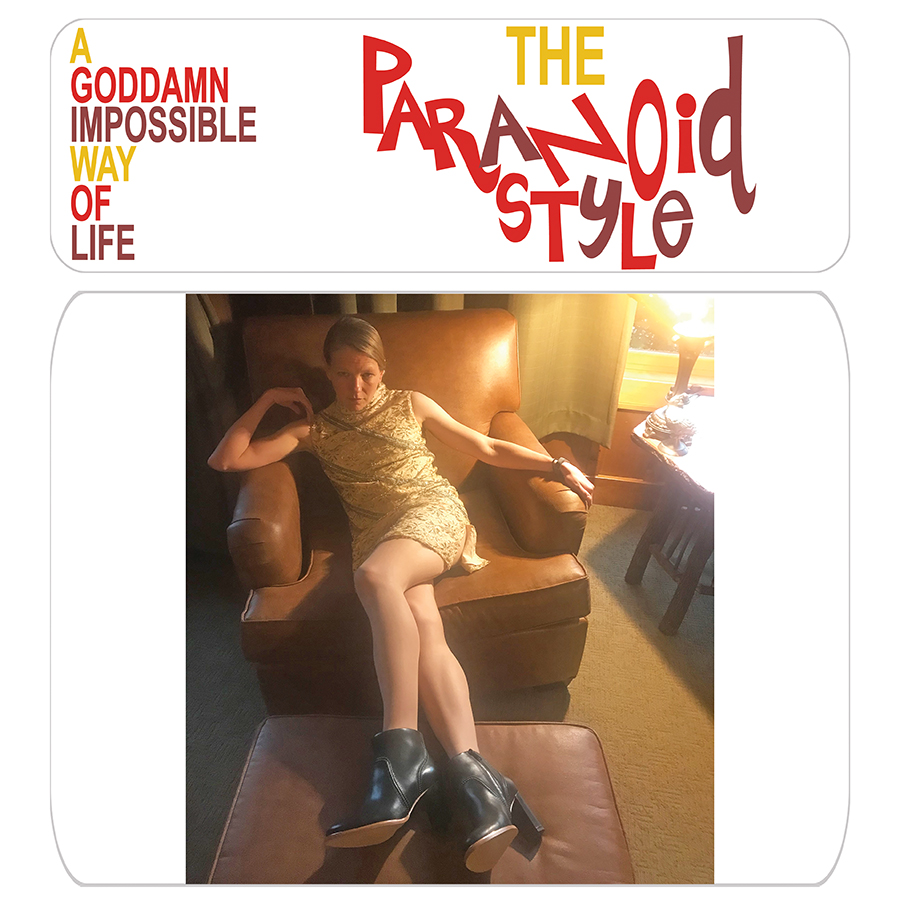

Musical Jumper Cables: A Conversation with The Paranoid Style’s Elizabeth Nelson

music

By Owen King

My dear friend Elizabeth Nelson’s songs are painfully, relentlessly funny, and also just relentless. They are musical jumper cables and I couldn’t do without them. I was thrilled to have a chance to talk with Elizabeth on the occasion of the premiere of “Turpitude,” the new single from her band The Paranoid Style’s latest album, A Goddamn Impossible Way Of Life. Elizabeth is a superb critic and essayist as well, and she writes regularly all over the place.

OWEN KING: The title track of your new record, A Goddamn Impossible Way Of Life, is largely about the Cincinnati Who concert in 1979 that ended in tragedy: eleven people died trying to get inside Riverfront Coliseum. Much of your focus is on how The Who proceeded to put on their show unaware of the awful thing that had happened. It’s a disturbing subject for an incredibly catchy pop song, both in terms of the specifics, and in terms of the way it gestures, generally, at all the horrible, inhuman occurrences that are taking place every single second while we carry along. Probably the best comparison I can think of is Warren Zevon’s “Boom Boom Mancini.” It’s that bracing. Can you talk about how you wrote “A Goddamn Impossible Way Of Life” and why you chose that particular song as the title track?

Elizabeth Nelson: You know, it’s obviously a terribly upsetting story—a horrifying tragedy. And I was listening to Roger Daltrey being interviewed recently, like forty years after the fact, and it was clearly something that continued to bother him tremendously, as one would expect. But as he described the band’s ignorance of the situation while on stage, and how they had thought it had been a great show, and I thought of all the anger and nihilism that could characterize Who concerts even at that point, it struck me as being like something from antiquity—like something Sophocles might have written. This unbound rage, the feverish excitement of the audience to be near this loud, violent band, the deadly stampede and then the band being compelled to perform the ritual even after a massacre. The idea of them encoring with “Summertime Blues” by Eddie Cochran, one of rock’s early martyrs. It just fucked me up to think about this. So I wrote the song. It’s also intended as kind of a sequel to my friend Lisa Walker from Wussy’s song “Teenage Wasteland”—an incredible song, one the best songs I’ve ever heard—but hers is kind of the story of the liberating power of hearing The Who in all of its unhinged, blunt force. Whereas mine is more like: But what happens when that energy takes a wrong turn? Once it’s out there, it’s kinetic and not easy to control. A lot of populist rock is like this, as well as politics. You whip up a mob and you think you know what it will do. But at a certain point you’ve got no idea any longer.

OK: Your songs are packed with references to bands and to rock and roll history. In “Turpitude,” for instance, you make glorious use of Mojo Nixon to ground the song in time, and “The Peculiar Case of the Human Song Generators” is a lovely tribute to They Might Be Giants. You’ve written lots of rock criticism and I know you are deeply devoted to the form. You’ve also been writing a beautiful series of personal essays for Oxford American. Do you see your music as an extension of the other kinds of writing that you do, or is it a separate thing altogether?

EN: Oh no, it’s very much of a piece to me. The part of my brain that writes songs or criticism or for TV or what have you is very integrated. It’s very much drawing from the same well. That’s the reason the album and my Oxford American column have the same name—A Goddamn Impossible Way Of Life. I have a tendency to fixate on a handful of topics and those manifest themselves in whatever medium I happen to be employing on any given day. One way to listen to the new Paranoid Style album is as a companion piece to the Oxford American column, although I am always quick to caution that one need not be familiar with the other project in order to enjoy both of them. But taken together they might brighten different corners.

OK: For sheer drollery, I would contend that The Paranoid Style has no peers. Consider this lyric from “An Endless Cycle of Meaningless Behavior”:

In the 50s, Greenspan declared Ayn Rand his savior

An endless cycle of meaningless behavior

Played clarinet and sax alongside Stan Getz, and then he went to Juilliard, which isn’t as easy as it sounds

But at the same time, as funny as it is, it’s so horribly, profoundly sad—he chose Ayn Rand over Stan Getz! You don’t know whether to laugh or cry. Things in our country are so awful right now, I lean to the latter. What do you see as the function of humor in your writing? I hate how stiff that sounds! Maybe what I mean is, is the humor what you use to get the medicine to go down, or is it the medicine?

EN: I think the humor is part creative strategy and part defense mechanism, and I don’t know if I can identify where that line is. I will say that it comes as second nature to me, that my songs have always tended to have setups and punch lines, and in some cases, the more troubling the topic, the more I’m inclined to add a joke or two into the mix. And I guess I like the challenge and the dissonance of wringing laughs out of ugly subject matter—the same as I enjoy that kind of thing in the writing of Leonard Cohen or Courtney Barnett or whomever. But I also feel an increasing awareness that this is a way in which I mitigate something that upsets me, and maybe it provides a certain distance that makes me more at ease. I’m attempting to be more cognizant of that in my writing: if something is sad, just let it be sad and try and live with it. There’s always going to be humor in the material, but I want to try to have a clearer perspective on if I am adding a joke because it’s in the service of the song, or if I’m adding it as an avoidance tactic for dealing honestly with the emotional core of the piece. I do not expect this will be a simple process.

OK: What was the biggest challenge of making this record? Or is the challenge what comes after? I know you’d make music no matter what because you love to do it, but it is hard to get people to give stuff a listen.

EN: Well, I have or attempt to have realistic expectations for what I do. The challenge of getting people’s attention is beyond daunting for even the most populist entertainment, and this isn’t a Marvel film or a Vampire Weekend record we’re talking about. Not to knock those things, but all the king’s horses and all the king’s publicists can barely train the public on the most mainstream of enterprises for more than a couple weeks. So people will come to The Paranoid Style by word of mouth or happenstance, or in most instances maybe they won’t at all. I’m lucky to have a great and supportive record label in Bar/None, and we know how to work econo and keep things affordable, but there certainly are not the resources to buy into the consensus-generating media and PR complex, and frankly I’ve got very little appetite for how that game is played in the first place. I’ve seen that from both the journalism and the music side, and it’s not for us. Having said that, we tend to have loyal and passionate fans, and they tend to be the sort of people whose endorsement means a lot to me. Maybe there are only a few thousand of them, but it’s still more than you’d want over for a dinner party all at once. I do sometimes get frustrated that the music isn’t getting to certain people who I think might really enjoy it, but I try to be equanimous about the reasons.

OK: What is your capacity at the Lawyers, Guns & Money blog, and how did you end up writing for The Ringer?

EN: Oh! Well my capacity at LG&M was a great and fun surprise. I’ve been a super fan of that blog for years and eventually solicited them to write a few things, and those went well enough, and then they ultimately asked me to be on the masthead full-time, and I was totally flattered and obviously agreed to that before they could wise up and come to their senses. And I’ve got a no-trade clause in my contract, so they’re stuck with me. Sort of similar with The Ringer, a publication I’ve deeply admired for a long time. I eventually was contacted by one of the editors asking if I was interested in pitching. What a collection of writers they have: Adam Nayman, Brian Phillips, Megan Schuster, Lindsey Zoladz, Justin Charity, Katie Baker. And on and on—really a murderers’ row. I can’t think of two greater publications to be involved with.

OK: You spent several months before the midterm elections working with Full Frontal With Samantha Bee. Can you describe what that project was like and how that occurred? Do you like working in television, and would you like to do more of it?

EN: For sure. The Full Frontal project was incredibly fun. I was hired as part of a team that created a game spinning off from the show—essentially a series of civics-based quizzes that Sam Bee hosted and you could play on your phone called “This Is Not A Game: The Game.” It was enormously cool and interesting to get to work on a staff with those folks, and I gained a lot of insight into how a topical comedy show like that functions. I’ve worked a lot in television in different capacities for VH1, Logo, Disney, and even The Weather Channel. I’ve done everything from writing scripts to designing copy that goes in subways or on the sides of busses. Everything about television fascinates me, and I’m always psyched to do more. One thing I’ve always wanted was to be in a writer’s room full-time for a series, just to have the opportunity to see stories get broken and taken to the screen. There are a couple of opportunities out there currently that I can’t get into too much detail about, but which I’m hopeful may come to fruition.

OK: Besides your band and your work in journalism and television, you also have a time-consuming job in public policy. Can you describe that work? I’m curious why you feel the need to remain in that arena. If nothing else, I’ve known you for years, and I’ve never understood where you find the time.

EN: I work in education policy, which was the thing I was trained for in school besides music. I am a consultant for a New York–based nonprofit called MDRC, which frequently partners with the Department Of Education in an effort to find solutions for struggling students in American schools. I used to be at MDRC full-time, but shifted to more of a consulting capacity when my other projects got more complicated. But I still work very closely with them, and much of my days are spent attempting to help evaluate literacy interventions at schools in DC and Baltimore. I have the easier side of it, but the work can be very difficult and demoralizing, and my colleagues at MDRC are the smartest, best, most principled people I know. No matter what happens, I always intend to keep a hand in policy work and social science. There’s something about watching people apply themselves to helping children read at an appropriate grade level that really gives you a lot of perspective on whether or not you’re going to get a rad review in Pitchfork. I mean, if I ever lose that perspective, then I’ll have failed in a really fundamental way.

OK: Finally, I’m wondering what remedies you would recommend at what feels like a low point in our politics. Is there a way of resetting?

EN: It’s been my observation and frustration that the American left continues to lose ground because in too many cases we shrink from doing the tedious things. And by that, I mean organizing on a local level in order to build grassroots constituencies in regions where Democrats should compete and have been traditionally successful, but haven’t recently. One of the major drivers of the GOP’s rise to power has been the deep attention they pay to the hyper local. I’m talking about voting in elections for city councils or state houses or school boards or local charters. That’s how you see certain states like Alabama or Missouri passing astoundingly crazy bills that cut against even the harder instincts of the national Republican party. Because they literally control every element of that state: governorship, courts, legislature. This is boring but that’s sort of the point. I need to do a better job of this as well. Life is busy and hard, and everyone can be forgiven for missing city council meetings. At the same time we should never be out-organized. Working people need to stick together and remember our shared labor. That forensic attention to detail and camaraderie once ruled the day, and I believe to my soul it can again.

More music