New Light on the Dark Lady: A Conversation with Caroline Randall Williams

Interviews

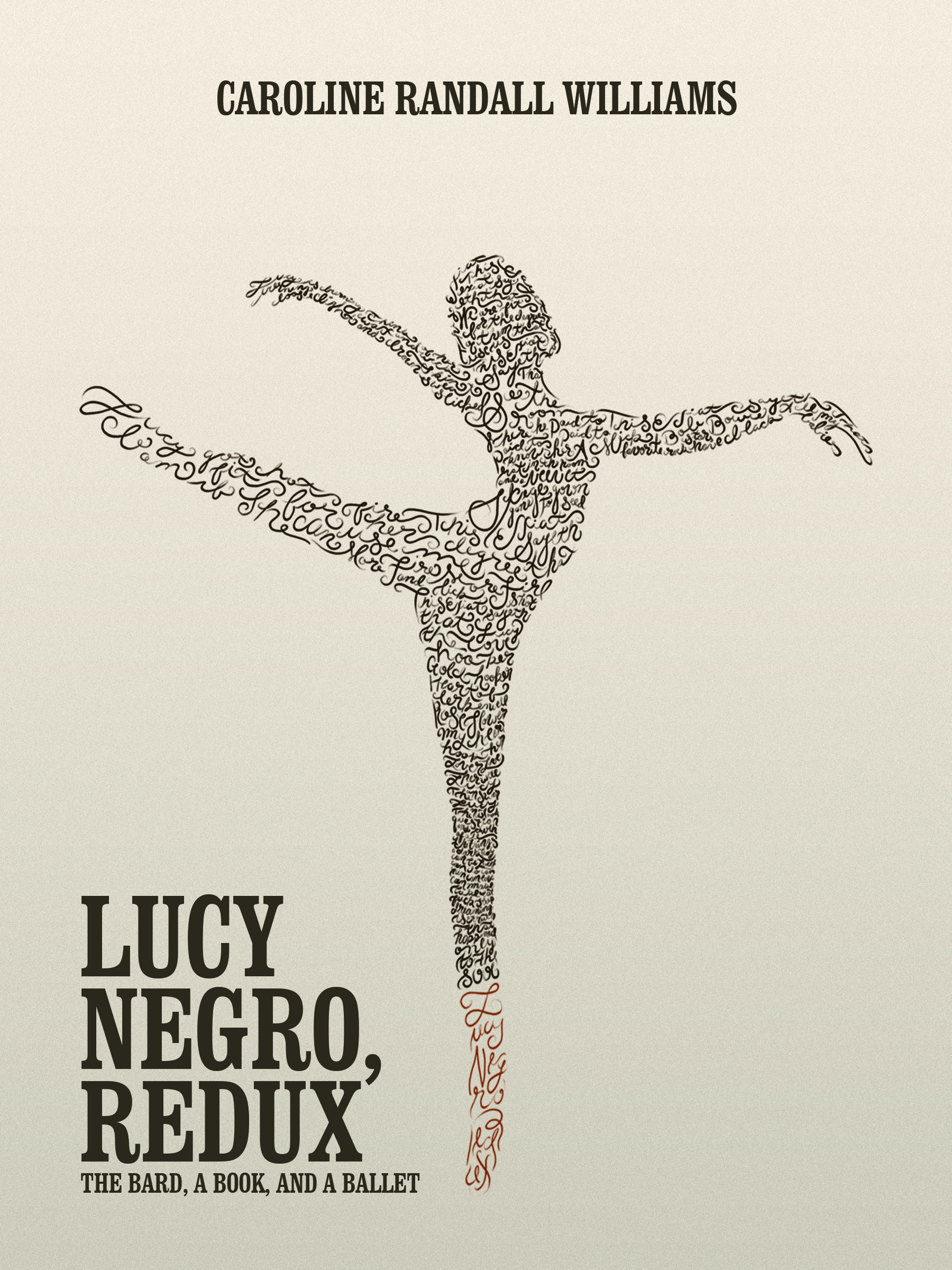

In 2015 a young poet from Nashville, Tennessee, named Caroline Randall Williams published a book titled Lucy Negro, Redux, imagining the famous Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s sonnets as a black woman. Williams’s book is mostly a collection of poems but features delightful prose passages, as well, telling among other things the story of her trip to England to meet with a professor named Duncan Salkeld. Salkeld’s scholarship, like Lucy Negro, Redux, pursues the possibility that Shakespeare may have modeled the Dark Lady after a black woman who lived in England during his day.

Last February was a big month for Williams and for the Dark Lady as Williams imagines her. Not only was Lucy Negro, Redux reissued by Third Man Books, a prestigious press, but also the Nashville Ballet premiered Attitude: Lucy Negro Redux, by Paul Vasterling, a ballet based on Williams’s book.

A few weeks back, I caught up with the poet via email and picked her brain about the experience of working with the likes of Salkeld and Vasterling—and, in a way, with the Bard himself.

GB: Reading your book, I remembered The Savage Detectives, by Bolaño. The Caroline character in Lucy Negro, Redux strikes me as being, among other things, a cultural detective of sorts. Could you say something about the relationship between cultural sleuthing and the making of literature?

GB: Reading your book, I remembered The Savage Detectives, by Bolaño. The Caroline character in Lucy Negro, Redux strikes me as being, among other things, a cultural detective of sorts. Could you say something about the relationship between cultural sleuthing and the making of literature?

CRW: First, let me say that for all intents and purposes, the “Caroline character” and I are really one and the same. Or, at the very least, she is my attempt at articulating my experience of discovering Lucy. I think the language I use even to describe that experience, or that distinction, speaks to your question. Making literature, for me, is probably always going to be an exercise in cultural sleuthing—I don’t know how to bring new insight to life without plumbing the recesses of the past. Or maybe I just don’t want to? Hunting down the old stories, or finding new apertures through which to view old ideas (or texts, or whatever else)—that’s where the work is.

GB: In your book Caroline says that she “badly” wants Black Luce [a London brothel owner of the Elizabethan era] “to be the Dark Lady that Shakespeare loved.” If the persona could lay hands on the proof she seeks, what would this confirmation mean to her?

CRW: Again, I think I’ll just tell you what the confirmation would mean to me, because she is all of me that is to do with Lucy. I want Black Luce to be Shakespeare’s Dark Lady because it would mean being able to go back to all of those sonnets and see myself in them. Physically. “If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.” My black, wiry hair. “Beauty herself is black, / And all they foul that thy complexion lack.” My complexion. “Thy black is fairest in my judgment’s place.” My fairest black. You see where I’m going with this.

GB: How do you think the news would impact Shakespeare’s legacy?

CRW: I hope that it would mainly be to the good, that it would expand his audience. There is always the fear that it would cut him off from more conservative readership, but I think the gain of having this particular form of representation (re: the black aesthetic) confirmed within an already canonized body of work would be extraordinarily uplifting and inclusive.

GB: I enjoyed the call-and-response element of your book, the way it places itself in conversation with Shakespeare’s sonnets, echoing them but also departing from their formal patterns. How would you describe the relationship between the forms your poems take in this book and the sonnet form that Shakespeare uses?

CRW: When I think about the sonnets, and my relationship to them, the first two words that come to mind are irreverent and obsessive. I love the idea of form, and of formality, both in poetry and in life. I love a well-ordered gathering, a silly social rule, a canonical text. But I want to be allowed to put any of those things through my filter; I want to articulate [formality], experience it, refract it through my own lens. That’s what imposing the idea of Lucy does to the content of Shakespeare’s poems. That’s how my broken “sonnets” are hoping to engage with the more traditional sonnet structure. A present black woman’s reframing of an old white man’s conceit.

GB: Speaking of form—the prose passages that chronicle the Caroline character’s time in England are so fun to read. Do you think of these as prose poems, snippets of essay, or something else?

CRW: At last. An easy question. The prose passages began as one contained personal essay. I began writing it as sort of a supplement to the Lucy poems—I didn’t know then that she was going to get a whole book. The poems kept coming, however, and they were rangy and scattered across many temporal and geographical spaces, but all hoping to speak to the same woman, or the same idea of womanhood. And miraculously, the essay was already there, and felt like the natural throughline to help me translate my wild, many-voiced woman to the reader.

GB: How did you differentiate between the material for prose and the material for verse?

CRW: I’m not sure that there was a deliberate differentiation at first. I’d begun writing the sonnets at the middle-ish section of the book, and then the essay came along. After the essay, I realized that I wanted to find ways to continue exploring Lucy’s story through poems, and essentially allowed myself to get obsessed with every line of inquiry opened through the act of writing the essay. “Black Lucy Negro III,” for example, is a poem that came from a place of wanting to tell the [story of my visit to London] with a more lyric voice—so the material is really a shared thing.

GB: If I may be gossipy for a second, what is Professor Salkeld like in real life? The book offers a delightful description of his appearance, but I’m wondering about his personality and his attitude toward the Lucy Negro, Redux project.

CRW: I describe him in the book as being “happily chagrined” by my initial email; to some degree I think that’s very much how he experienced me throughout the time we worked together. He was enthusiastic, earnest, and engaging about his material; he was amused and a bit incredulous that a twenty-five-year-old black girl had flown from Mississippi to come see his research and visit Elizabethan prison records.

He has been wildly gracious and supportive about every development to do with my book and the ballet—it’s a huge and precious wish of mine that we can take the ballet to London so that he can see it.

GB: I read somewhere that a famous musician once asked a French poet whether it would be okay to set one of his poems to music. The poet replied, “I thought I already had.” Did you have any reservations along these lines when Paul Vasterling of the Nashville Ballet said he wanted to recast Lucy Negro, Redux as a ballet, or did it feel like a cool idea from the get-go?

CRW: Not one reservation. Paul and I had a meeting of the minds from the first time we sat together in his office. I love your anecdote about music existing already in a poem, but for me, there is always a want for more. More cadence, more rhythm, more texture. I hope there is a lot of music in my work, but I love a mash-up, a sample, a remix. Adding music was very much a “more is more” opportunity where this book is concerned.

More Interviews